Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

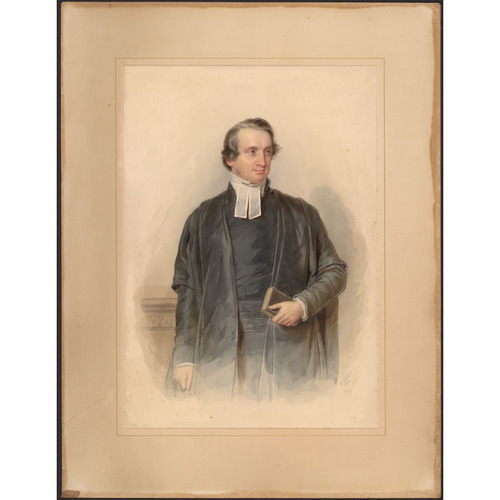

HILLS, GEORGE, Church of England bishop; b. 26 June 1816 in Eythorne, England, son of George Hills and Diana Hammersley; m. 4 Jan. 1865, in England, Maria Philadelphia Louisa King, daughter of Vice-Admiral Sir Richard King; they had no children; d. 10 Dec. 1895 in Parham, Suffolk, England.

Born into a stern, disciplined naval family, George Hills was educated first at King William’s College, Isle of Man. At the University of Durham, from which he graduated ba in 1836 and ma in 1838, he came under the influence of Hugh James Rose, a prominent Tractarian and historian. Hills was ordained priest on 6 Dec. 1840 and after a brief period as curate in North Shields went to Leeds to serve under Dean Walter Farquhar Hook, a leading figure in the Tractarian movement. The parish church, where Hills held a lectureship, was the centre of a large working-class community and a showpiece for the powerful spiritual influence the Tractarians had gained in the Church of England. When the division of Leeds parish became necessary, a new church, St Mary’s, was built and Hook offered Hills the incumbency.

From 1845 to 1848 Hills developed at St Mary’s some of the parochial principles that were to become his hallmark. He was, according to his curate J. H. Moore, “a capital man to be with,” impressing on the seven or eight clergymen whom he supervised, and who lived with him, his passion for religion, his enthusiasm for the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel and for parish activity, and his distaste for emotionalism and slipshod work. It was an approach to the challenges of Victorian religion perhaps derived from conversations with William George Ward and John Keble, intellectual leaders of the Tractarian movement. Hills wrote approvingly that Keble wished to see “monastic institutions revived in a modified way.” The intensity of this early experience of dedicated mission in a community of young men was not, unfortunately for him, to be recreated in his later career in British Columbia.

In 1850, at the age of 33, Hills was appointed vicar of St Nicholas, Great Yarmouth, a large parish with a staff of curates and several church schools. He built a new church for the beachmen, initiated regular training for his clergy, and ensured that the sick and unbaptized were systematically visited. A model of mid Victorian energy, organization, and Christian civilizing zeal, he acquired a reputation beyond the boundaries of the diocese of Norwich. In 1858 Hills was awarded an honorary dd by the University of Durham.

With the discovery of gold and the establishment of the crown colony of British Columbia in 1858, an Anglican diocese, including the mainland as well as the older colony of Vancouver Island, was created with the financial support of the English philanthropist Angela Georgina Burdett-Coutts. On her recommendation Hills was selected the following year to be the first bishop of Columbia. The eminent Victorians in education and science he met through her patronage undoubtedly aided him during the several months he spent in England preaching, lecturing, and building support for his Columbia mission. In one of his fund-raising speeches, at the Mansion House in London, Hills spoke of his new responsibilities. “In Columbia let the institutions of England, her freedom, her laws and her religion flourish. Let there be a union of philanthropic and religious minds. Let the British territory be a spot where sympathy will be shown the oppressed.” The combination of Christianity and imperialism which was to characterize his work was thus established before he encountered the particular conditions of his own diocese. Yet his role would be both evangelical and pastoral, secular and episcopal. Though some may have thought the rising young vicar was abandoning a promising career for a mere colonial bishopric, Hills shared the optimism of the Colonial Office, which predicted a railway and a million new settlers in British Columbia and Vancouver Island within the decade.

At the time of Hills’s arrival in Victoria in January 1860 the two colonies were peopled largely by Indians. European settlements were small and dispersed, and included Hudson’s Bay Company trading posts, the villages of Victoria, Nanaimo, and New Westminster, and a floating population of miners in the interior. At Fort Victoria, Anglican services had been held since 1836 by the company chaplains Herbert Beaver, Robert John Staines*, and Edward Cridge; missionary efforts had been made in some Indian communities. Governor James Douglas*, a former HBC officer, had been appointed by London in 1851 but was not of the calibre of men to whom Hills had been accustomed to defer. “He does not know the tone of the upright and high minded gentleman. His appointments have been subservient to himself and not men of independent feeling and high intelligence. A good deal of this may be owing to the paucity of worthy persons and partly to his never having lived in England or in any civilised community.” Such an attitude did not endear the new bishop to the old fur trade élite. Hills was seen as too finely attired for a frontier colony, lacking in humour, reserved in manner, and aloof from much of Victoria’s society. In 1868 he recalled a ball at Government House where “the invited guests were continually shaking hands with the servants and one guest pointed out to the Governor another guest pocketing the sweets.” He attributed the low tone at the other end of the social scale, among Canadian settlers, to their Methodism. Not only were they deficient in “courage and enterprise, spirit and energy” but they were, on the whole, “conceited and lacked reverence for authority.” The maintenance of the symbols and dignity of duly constituted authority in an ordered society became part of Hills’s appointed mission in Britain’s new colony.

His move to British Columbia was softened by the presence of his “faithful couple,” William Bridgeman and his wife, who had served him at Great Yarmouth and who tended his home, garden, and farmyard in Victoria. It was a delight to have “the gratification of a herring for breakfast; cured by a Yarmouth man.” Norwich men also came as clergy. The presence of the Royal Navy at Esquimalt provided links with home as well. Hills, the eldest son of an admiral, frequently held services for officers and men and dined in the wardroom. Like most newcomers, he was impressed by the physical beauty of British Columbia and learned to rejoice in the hardship of backwoods travel. “I have found myself able to walk my 20 miles a day. I have learned to sleep as soundly on the floor of a log but or on the ground, as in a bed, and to rise refreshed and thankful; to clean my own shoes, wash my clothes, make my bed, attend to horses, [and] pitch tents.”

Hills needed all this youthful vigour to face the problems of his enormous diocese. His challenges were those of most colonial bishops of his generation: the search for suitable clergy, the creation of educational and social institutions, and, above all, the securing of a sound financial base for the diocese and its missionary outposts. To meet the needs of scattered settlements, miners’ camps, and missions to the Indians, he recruited clergy from England. By 1865 the towns of Victoria, Nanaimo, Esquimalt, and Saanich on Vancouver Island and Lillooet, New Westminster, Hope, and Sapperton on the mainland had regular services. Work with the Indians was carried on at Nanaimo by John Booth Good and at Victoria by Alexander Charles Garrett, and missions were set up on the lower mainland and at Lillooet. The bishop toured his diocese, including the interior, putting in place rudimentary diocesan organization and holding services. He also prompted the establishment of secondary schools for children of colonists, such as the Boys’ Collegiate School and Angela College for girls (1866) in Victoria, and residential schools for native pupils such as All Hallows’ Indian Girls’ School, founded in Yale in 1884 by Anglican sisters from Norfolk, England.

These endeavours were financed from a variety of sources. In the northern part of the diocese the Church Missionary Society supported missionaries such as William Duncan* and William Henry Collison, while the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel sent several missionaries to the southern mainland. Hills, courageously, had created his own independent source of revenue, the Columbia Mission Fund, and was known as “a splendid money raiser.” In retrospect, however, he was a poor manager of money. He had personal control of the Yarmouth Fund and the Church Estate Fund, but he was more ready to be led by short-term needs than long-term financial considerations, letting go “for taxes” a valuable piece of what would become downtown Vancouver. He relied heavily on support in England and on his own ability to raise funds and was deeply distressed when these failed him, particularly when, in 1879, the SPG reduced its grant.

Nevertheless by the time British Columbia entered confederation in 1871, Hills had about 18 clergy and catechists, had built two schools in Victoria as well as parsonages and schoolrooms elsewhere, and had some self-supporting parishes. From the beginning he had sought a position of pre-eminence for the Church of England, and this he achieved. Some believed he had attempted to create an established church, but when the governor offered land grants Hills refused them, in part because such privileges had not benefited his church in other jurisdictions, and in the Province of Canada had even strengthened the Methodists. He realized that the “aristocratic” associations of the Church of England were not immediate advantages in a country held together, as one miner told him, by “Gold, Gambling, Whisky & Women.” Hills was determined not to give “cause” to Roman Catholics and Methodists, both of whom he came into conflict with and whom he saw as social inferiors and theological enemies.

Bishop Hills was by no means a man of religious tolerance. He believed non-sectarianism to be erroneous and American and opposed it on both grounds. A sympathizer with the Oxford Movement, he had reason to cherish the prospect of a church free from state law and power. As an imperialist he believed that the role of the church in British Columbia was to help create an ordered society – the reproduction of England – by having a respected clergy in place, by flying the royal standard on 24 May, by encouraging cricket and other “civilized” pursuits, and by exhorting “the British miners to keep up a good British feeling wherever they went.” He acknowledged, “We must be content with a large preponderance of the American element of the California stamp,” but argued, “If we are wise and faithful as clergy as well as numerous enough we may see society as it ought to be.

Hills’s personal tragedy was to see the ordered society he strove for broken by dispute and eventual schism within his own diocese. His cathedral in Victoria became a centre of dissent and his episcopal authority was challenged by its dean, Edward Cridge. The tragedy was made more poignant by the fact that the dispute derived in part from local hostility to what he held dear in the English church. Cridge, a Cambridge evangelical who was well-connected in the old fur-trade élite, might have been irked by being passed over as bishop, but was probably more upset at having to submit to the authority of a man so sympathetic to the Tractarians. Personal friction was evident early over issues such as the centralized financial organization created by Hills and the difficulties emerging at the Metlakatla mission to the Tsimshian Indians run by Cridge’s friend and protégé, William Duncan. Cridge and his supporters were also suspicious of Bishop Hills’s plans for a synod, which they saw as a “system of centralisation highly prejudiced . . . to life in the Church” that would give Hills independent authority “at a time when there were fundamental differences on doctrine, order and discipline.” For evangelicals, as Cridge pointed out, “the divine authority is in the body of the church itself.” Hills, however, argued that the bishop already had divine authority and that through a synod he was, in fact, asking the clergy and laity to share it with him.

The major dispute erupted in 1872 when, at the consecration of Christ Church Cathedral in Victoria, the archdeacon of Vancouver, William Sheldon Reece, one of Hills’s young men, spoke warmly of the new liturgical life in the church. The cathedral was also Cridge’s church and, as the Daily British Colonist noted, Reece’s sermon was both “indiscreet and in bad taste.” The dean replied to the sermon immediately, creating a furore in the cathedral and later throughout Victoria. His behaviour brought him a letter of censure from Hills. The Anglican congregations divided and relations between the bishop and the dean deteriorated. In the summer of 1874 Cridge denied Hills the right of visitation to the cathedral, and the bishop moved quickly to bring Cridge to trial, first before a specially constituted ecclesiastical court and later before the civil court of the province [see Sir Matthew Baillie Begbie], both of which found in favour of the bishop. The following year Cridge took a large part of the congregation into communion with the Reformed Episcopal Church, and he became a bishop himself in 1876.

The dispute was caused by both personal and theological differences. Yet Hills was not the ritualist that his enemies portrayed. He was undoubtedly a Tractarian, but a man for whom the Church of England was more important than any one party within it. The church allowed a wide latitude of belief, and the disagreement in British Columbia was between different ideas of church government. Issues of episcopal authority were much to the fore in mid Victorian England, but in addition, at this outermost edge of empire, Cridge’s challenge threatened the bishop’s chosen and natural order and his civilizing mission.

Unshaken in his sense of rightness and convinced that his duty had been done and authority must be upheld, Hills observed that “it is the day again of small things” when, with little congregations, the principles of the church could be clearly taught. His optimism was necessary because not only had the Cridge affair brought the church into disrepute, but it had also led to the withdrawal of many of the wealthiest parishioners at a time when support from England had begun to decline. The growth of population in the south and an expanding, unruly evangelical mission in the north in the 1870s led Hills to create two new dioceses in 1879: New Westminster on the lower mainland, and Caledonia in the northern part of the province. Acton Windeyer Sillitoe was named bishop of the former and William Ridley of the latter. Hills himself retained Vancouver Island, with the original title of Columbia, until 1892. No longer a missionary or planter of the Christian standard during this period, he was primarily a manager of lands and property, a bibliophile, and an enthusiastic and learned gardener. In earlier years his wife had taken part in the educational and social life of the diocese and had acted as her husband’s secretary. Her health deteriorated and before her death in 1888 at the age of 65 she was subject to epileptic fits, depression, and possibly dementia. Her husband’s epitaph on her gravestone, “She hath done what she could,” perhaps says more about Bishop Hills’s austere manner than her devotion to duty.

Hills himself stayed on at Bishop’s Close, a rambling iron building in a vernacular Gothic style similar to that in many such outposts throughout the empire, surrounded by flower gardens. During his last years there it was said of him that British Columbia became his whole world. Confederation with Canada had robbed him of easy access to influence and to the prestige and satisfaction he had found in his London connections. Schism in his own church had deprived him of the social support of many important men in Victoria. He remained at heart a colonial bishop, noting with some pride that he was the senior bishop in active duty in the colonial church. When he finally agreed to retire in 1892 he returned to England as rector of Parham under Bishop John Sheepshanks of Norwich, who had earlier been one of his more satisfactory choices for pioneer work in British Columbia. There Hills organized a system of district visitors in the parish, tended his garden and greenhouses, conducted regular services, and voted Tory in the election of 1895. An idealist, a man of courage and optimism, he was described by George H. Cockburn as “one of God’s extremists, limited only by his Anglicanism.” He was a man of firm church principles for whom the 19th-century expansion of both the British empire and the Church of England gave undeniable evidence of the wisdom of the divine will. Providence, equally, had enabled Hills to give his life in service of three masters: church, God, and country.

Publications by George Hills include: A sermon preached at the farewell service celebrated in St. James’s Church, Piccadilly, on Wednesday, Nov. 16, 1859, the day previous to his departure for his diocese . . . with an account of the meeting held the same day at the Mansion House of the City of London, in aid of the Columbia mission (London, 1859); Pastoral address of George Hills, D.D., bishop of Columbia, to the clergy and laity of the diocese of Columbia, March 26, 1863 (Victoria, 1863); and Synods: their constitution and objects; a sermon preached in Christ Church and St. John’s, Victoria, January 1874 ([Victoria], 1874). His papers, including his diaries for 1838–95, are preserved in the ACC, Provincial Diocese of New Westminster Arch. (Vancouver); a microfilm copy is available at the PABC.

ACC, Provincial Diocese of New Westminster Arch., H. J. K. Skipton, “The life of George Hills, first bishop of British Columbia” (1912). Canterbury Cathedral, City and Diocesan Record Office (Canterbury, Eng.), Eythorne, reg. of baptisms, 6 Aug. 1816. PABC, G. H. Cockburn, “A tribute to George Hills.” B.C., Supreme Court, Judgment: bishop of Columbia versus Rev. Mr. Cridge; judgment rendered on Saturday, October 24th, 1874, at 11:20 o’clock, A.M. ([Victoria?, 1874?]). Colonial Church Chronicle (London), 1860. O. R. Rowley et al., The Anglican episcopate of Canada and Newfoundland (2v., Milwaukee, Wis., and Toronto, 1928–61). A. O. J. Cockshut, Anglican attitudes: a study of Victorian religious controversies (London, 1959). Susan Dickinson, “Edward Cridge and George Hills: doctrinal conflict, 1872–74, and the founding of the Church of Our Lord in Victoria, British Columbia, 1875”

Cite This Article

Jean Friesen, “HILLS, GEORGE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hills_george_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hills_george_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jean Friesen |

| Title of Article: | HILLS, GEORGE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |