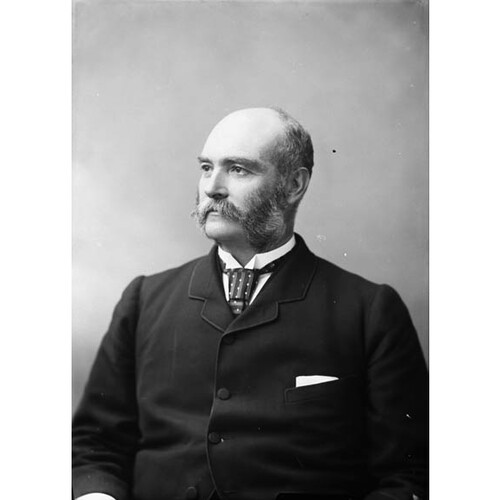

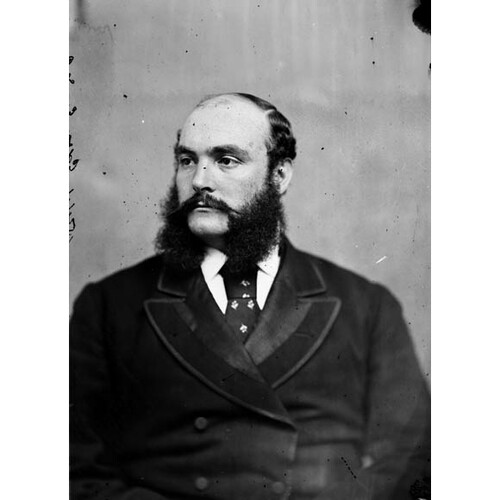

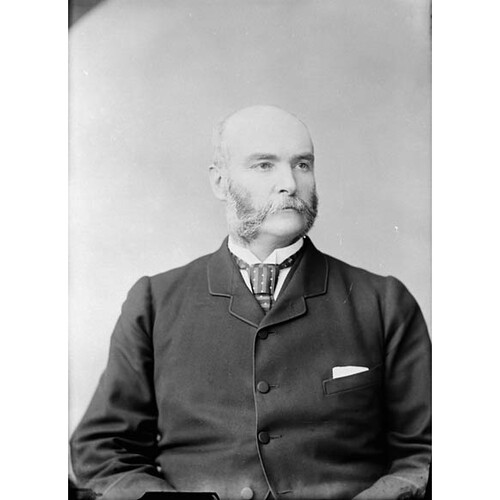

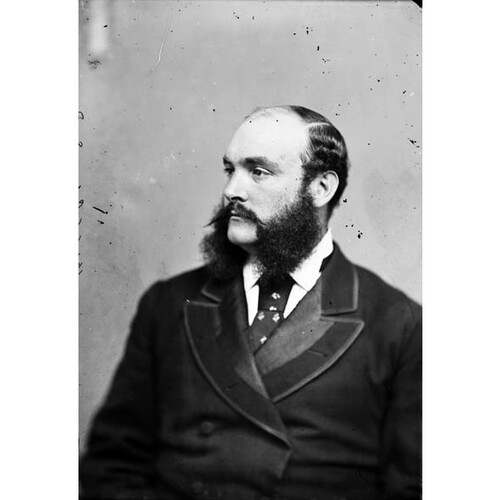

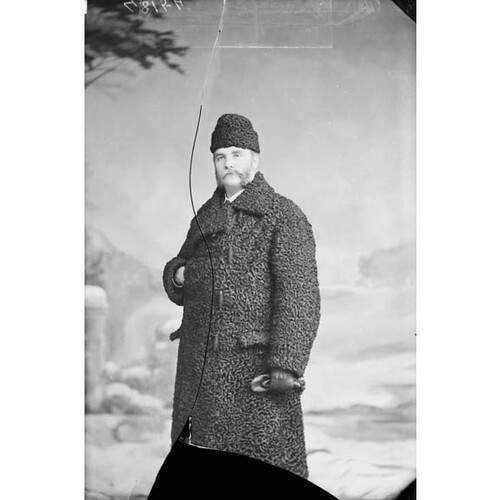

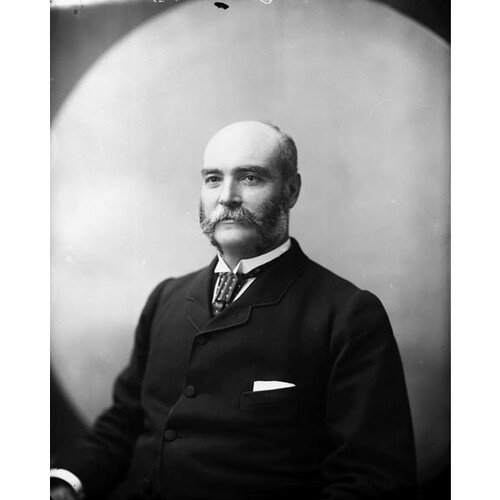

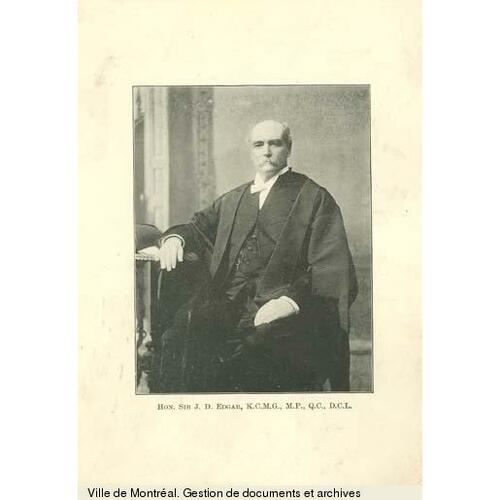

EDGAR, Sir JAMES DAVID, lawyer, journalist, author, politician, and businessman; b. 10 Aug. 1841 in Hatley, Lower Canada, son of James Edgar and Grace Matilda Fleming; m. 5 Sept. 1865 Matilda Ridout*, daughter of Thomas Gibbs Ridout*, and they had three daughters and six sons, including Oscar Pelham*; d. 31 July 1899 in Toronto.

James David Edgar was a descendant of an old Scottish family in Keithock, Forfarshire, who were prominent Jacobite supporters during the uprisings of 1715 and 1745. His parents immigrated in 1840 to Stanstead County, Lower Canada, where James was born. He attended private schools in nearby Lennoxville and in Quebec. After his father died, James moved to Woodbridge, Upper Canada, with his mother and two sisters and continued his education there. His academic achievements soon caught the eye of John Hillyard Cameron*, a prominent Liberal-Conservative politician, and in 1859 Edgar entered Cameron’s office in Toronto to study law. He was one of the outstanding legal students in the province and was called to the bar in 1864.

Upon completing his training, Edgar branched out in a number of directions. He entered the law firm of Samuel Henry Strong*, one of Toronto’s ablest lawyers. At the same time he joined the Globe as its legal reporter and editor. He also became legal editor of the Montreal Trade Review. His two small volumes on the Insolvent Act, published in 1864 and 1865, and a short study in 1866 of contracts and real estate, A manual for oil men and dealers in land, made him well known in the legal community. Over the next three decades he established a successful law practice in Toronto, specializing in civil law, and in 1890 he became a qc. While still in his 20s, he also made a name for himself through his literary and patriotic endeavours. He was president of the Ontario Literary Society in 1863 and later of the Toronto Reform and Literary Debating Club. He produced a popular poem, “This Canada of ours,” to honour confederation. Set to music by E. H. Ridout, it was to receive further recognition in 1874 in a contest in Montreal for national songs and ten years later during Toronto’s semi-centennial. In 1865 Edgar married Matilda Ridout, a member of one of the city’s most prominent families and later a historical writer of note.

It was to the field of politics that Edgar devoted most of his energies. In 1867 he was elected an alderman for St George’s Ward in Toronto, but was unseated by judicial decision. Under the guiding influence of the Globe’s editor, George Brown*, the Upper Canadian Reform leader, he moved into the ranks of the Reform party. Brown gave him an important organizational role in the 1867 Reform Convention in Toronto, as secretary of a provisional central executive committee, and later helped him to find a constituency to run in. Over the next few years Edgar played a central role in the organization of the party. Between 1867 and 1876 he was secretary of the Ontario Reform Association, and he was instrumental in revitalizing the ranks of its Toronto branch. During his brief stint in the House of Commons between 1872 and 1873, he was the party’s chief whip. It was a position he relished and during the Pacific Scandal he played an important role in organizing opposition attacks on the Conservative government, which resigned in November 1873. Although he was not in the house between 1874 and 1878, the years of Alexander Mackenzie’s administration, he was the Liberal leader’s chief political contact in Toronto since Brown had largely retired from active politics and Edward Blake*’s loyalty was uncertain.

The irony was that, despite his organizational skills, Edgar had considerable difficulty in winning his own seat. In the provincial election of 1871 he lost in the Niagara peninsula constituency of Monck by five votes. Although he was elected in 1872 to represent it in the commons, he was unable to hold the seat in 1874, and he lost three federal by-elections (Oxford South in 1874, Monck in 1875, and Ontario South in 1876) and the general election of 1878 in Monck. Part of Edgar’s problem was that he was still too closely identified with Brown and the Toronto Reformers, and with what the Conservative press, notably James Beaty’s Leader, characterized as “the black bottle brigade,” Liberal partisans who had used liquor to draw electoral support for Brown in 1867 and whose plan was to “centralize power in the Toronto junta.” Two Toronto constituencies rejected Edgar: in 1881 he failed to get the Liberal nomination in York East and in the general election the following year he was defeated in Toronto Centre by Robert Hay*. It was not until 1884 that the party finally found him a safe seat, Ontario West, which he would hold in the general elections of 1887, 1891, and 1896.

Returned to Ottawa in 1884, Edgar resumed his activities in the party’s back rooms. Once again he was appointed one of the parliamentary whips, this time by the new Liberal leader, Edward Blake. Edgar took the initiative in the attack against the Conservative government’s electoral franchise bill in 1885 and its North-West policy in 1885–86. Blake also appointed him the party’s railway critic, a posting for which he was ideally suited. In 1874, Mackenzie had sent him to British Columbia to renegotiate, with Premier George Anthony Walkem*, the railway clause of that province’s terms of union. From 1874 to 1882 Edgar had been active, initially as president of the Ontario and Pacific Junction Railway Company, in promoting a railway link between Toronto and Lake Nipissing to connect with the transcontinental route. Although neither of these ventures had ended in success, the experience enabled him to be an effective critic of the railway schemes of the government of Sir John A. Macdonald. More important, however, were Edgar’s efforts in building the organization of his party. Although officially the Liberals had never had a chief federal organizer, unofficially Edgar assumed a great many of the responsibilities. As one historian has described him, he was to the Canadian Liberal party what Francis Robert Bonham had been to Sir Robert Peel’s Conservatives in Britain. The range of his activities did not go beyond Ontario, the one exception being his attempt in 1885 to bring into the party Quebec Conservatives who had opposed Macdonald’s decision not to stay the execution of Louis Riel*. By 1887 under the leadership of Wilfrid Laurier*, Blake’s successor, Edgar had become chairman of the party’s parliamentary committee on organization. In this role he was in charge of the organization of federal by-elections over the next few years. He was also responsible for the distribution of party funds and literature, and for arranging Laurier’s first speaking tour through Ontario in the summer of 1888. In addition he acted as a liaison between the party and the Globe, of which he was a director between 1882 and 1889.

Edgar made his greatest contribution as a party organizer in the area of finance. Before 1887 the party had no systematic method of raising money. Although candidates frequently turned to the provincial or the federal party to assist them in their campaigns, they relied for the most part on moneys raised by their local associations or, in many cases, drawn from their own pockets. Following its disastrous defeat in 1882, however, the party developed a “subscription list” of prominent Liberals who could be relied upon to contribute to the party’s coffers, and after his election in 1884 Edgar was given responsibility for collecting the money. As part of the activities of his committee on organization, he prepared a plan to place fund-raising on a more formal basis. Instead of the haphazard method of collection formerly used, Edgar proposed that subscribers pay a fixed annual amount over a three-year period, and that the funds so collected be subject to the control of Laurier and the parliamentary committee. A major step in the building of a truly national Liberal party, the plan was the Liberals’ first attempt to raise, in a systematic way, a general fund that the party could draw upon at all times. Although the plan applied only to Ontario, it provided a blueprint that could be used in the 1890s by provincial organizations such as that of Joseph-Israël Tarte* in Quebec.

During the 1880s, too, Edgar figured significantly in the development of party policy. In response to the growth of sentiment in favour of commercial union and convinced of the need to find a “bold new policy” after he had inherited the leadership of a party which had lost three consecutive elections, Laurier sounded out his followers during the summer of 1887 on the possibility of adopting commercial union as party policy. Although Laurier himself was initially enthusiastic, Edgar was cautious. Like most 19th-century Liberals, he supported free trade with the United States because it would bring an end to the tariffs which, under the Conservatives’ National Policy, had allowed manufacturers to create monopolies at the expense of Canadian farmers and consumers. That November, in a series of open letters to Erastus Wiman*, the New York businessman at the head of the commercial union movement, Edgar maintained that a policy of unrestricted reciprocity would be superior to one of commercial union, most importantly because it met the objection that commercial union would deprive Canada of her separate identity. As Edgar saw it, commercial union would involve turning control of the tariffs over to some joint authority which, inevitably, would be subservient to the American Congress. Unrestricted reciprocity, on the other hand, would leave control of tariffs in the hands of the respective governments.

The letters appear to have been decisive. When senior members of the Liberal caucus met at the beginning of the 1888 session, they endorsed the distinction Edgar had made and recommended that unrestricted reciprocity be formally adopted as party policy. Shortly thereafter, the full caucus did just that. In some respects, however, the distinction was more apparent than real. Although unrestricted reciprocity seemed clear in theory, even some Liberals regarded it as an “unfortunate and bungling compromise” that was sufficiently ambiguous to be used by its opponents to cover all that commercial union implied, as Macdonald ably demonstrated in the general election of 1891, which the Conservatives won. More crucial, reciprocity was a policy that depended on the acquiescence of the American government, and for every indication from the United States that there was support, there were more signs that the Liberals were beating their heads against a wall. Although they did better in 1891 than in 1887, particularly in Ontario and Quebec, the strength of the Liberal vote may have been a tribute as much to Edgar’s organizational skills as to his skills as a policy maker. In 1893 the party dropped unrestricted reciprocity from its political platform.

The Liberals, however, had found another issue on which to attack the government: between 1891 and 1895 they brought charges of corruption against seven Conservative ministers. Edgar was not a member of the select committee on privileges and elections which examined charges in 1891 against two Quebec Conservatives, Sir Hector-Louis Langevin* and Thomas McGreevy, but he attended all of its meetings and helped shape the prosecution. Ultimately the charges led to Langevin’s resignation from cabinet and to McGreevy’s conviction. For Edgar, however, the Langevin–McGreevy investigation was the beginning of a campaign to discredit the government. During the course of the investigation, evidence had come to light that the minister of militia, Sir Adolphe-Philippe Caron*, had used his influence to obtain construction subsidies for two Quebec railway companies of which he was a director, and then channelled the funds to Conservative candidates in the province. On 6 April 1892 Edgar presented ten separate charges against Caron to the House of Commons and demanded that they be investigated by the privileges and elections committee. When the government referred them to an extra-parliamentary judicial committee and deleted the charges relating to election financing, Edgar refused to appear before it, despite Laurier’s urging. In the end the charges amounted to but a report of evidence in the sessional papers of 1893, and Caron remained a minister.

Edgar nevertheless did his best to keep these scandals prominent over the next few years. In 1893 he had a resolution condemning the government for retaining Caron in office placed before the Liberal party’s national convention in Ottawa. And in July 1894, on the basis of evidence from the McGreevy trial, he introduced a motion in the commons to censure Langevin and Caron. For Edgar, however, the results of the campaign were decidedly two-edged. There can be no doubt that the Conservative party in Quebec was severely weakened by the discrediting of such key organizers there as Caron and McGreevy. On the other hand, Edgar’s health deteriorated noticeably and, although he had moved to the forefront of the “prosecuting attorneys” in the commons, his image as a highly partisan machine politician had hardened. In the Liberal party of Wilfrid Laurier, intent on broadening its support beyond an Ontario base that had largely been Clear Grit, this was not an image that would hold him in good stead.

It has been suggested that Edgar’s star went into political eclipse in the 1890s because he failed to make the transition from 19th-century liberalism to the liberalism of Laurier and the 20th century. In some ways this was true. During the election campaign of 1896, Edgar continued to extol the virtues of free trade with the United States and to attack protectionism. In other respects, however, he made the transition much more steadily than some of his Ontario colleagues. Conservative critics on occasion described him as an anti-imperialist, but his vision of the empire and Canada’s role in it was remarkably close to the concept of the modern Commonwealth. Early in the 1870s he had flirted briefly with the Canada First movement [see William Alexander Foster*] and during the 1880s and 1890s he made a series of speeches proposing that Canada assume control of its commercial treaties and copyright legislation. When he talked about Canadian sovereignty, however, he did not mean that Canada should break its tie with the empire. “The loftiest conception of a Canadian nationality,” Edgar wrote in Canada and its capital . . . (Toronto, 1898), “is that our country should become part of a vast federation of free British nations, paramount in power, in wealth and in greatness.”

More revealing still was Edgar’s rejection of the nativist, anti-French, anti-Catholic strain of Ontario Gritism. He had been the first Ontario Liberal to commit himself publicly to support the Conservative administration in its refusal in 1889 to disallow the Quebec government’s Jesuits’ Estates Act [see Honoré Mercier]. The following year, like most of his Liberal colleagues, Edgar opposed D’Alton McCarthy’s bill to abolish the use of the French language in the legislature and courts of the North-West Territories. He was also the first of the Ontario Protestant politicians to denounce the bigotry and intolerance of the Protestant Protective Association [see Oscar Ernest Fleming*], a secret fraternal society and an offshoot of the nativist American Protective Association. Two letters of criticism by Edgar, addressed to the Globe and printed in pamphlet form by the Liberal party in 1894, played an important role that year in the successful provincial campaign of Liberal premier Sir Oliver Mowat*.

Nor did Edgar’s position on the school question in Manitoba, where the provincial government had abolished public funding of Catholic schools, have much in common with his Clear Grit heritage. Like most Ontario Liberals, he opposed “state aid to education of the slightest sectarian character” and tolerated separate schools in Ontario only because they had been “part of a pact and compromise” at confederation. Unlike many of his colleagues, however, he resisted the temptation to regard the plight of the Catholic minority in Manitoba as a question of provincial rights. Although he opposed the remedial legislation proposed by Conservative prime minister Sir Mackenzie Bowell*, he recognized that, in matters relating to education, provincial rights could be abridged and that the federal government had a role in safeguarding rights held by minorities at confederation. Following Laurier’s electoral victory in 1896, Edgar was thus able to play a leading role during the final stages of the drama. Acting as an intermediary from the prime minister’s office, he persuaded the archbishop of Toronto, John Walsh, to intervene to bring the Catholic hierarchy in Manitoba to support the Laurier government’s compromise with the provincial government of Thomas Greenway* – no separate schools but some religious instruction in public schools.

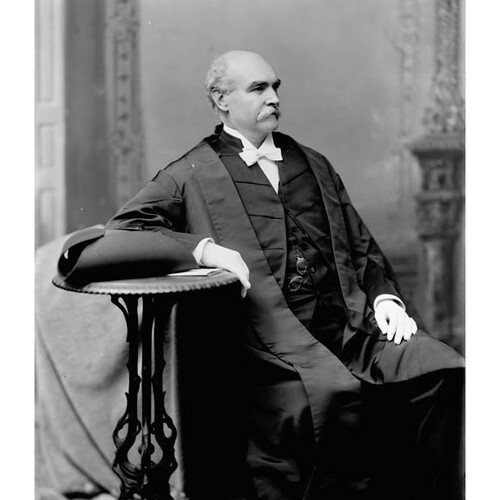

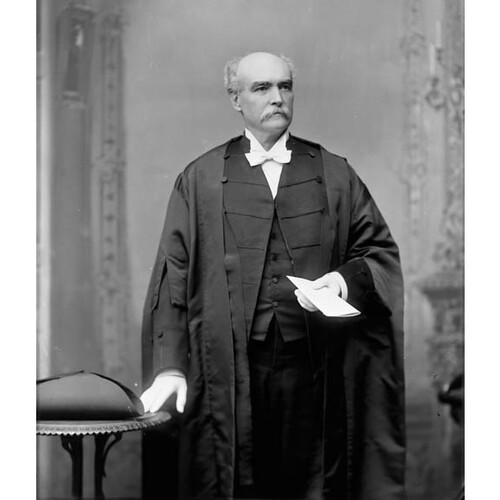

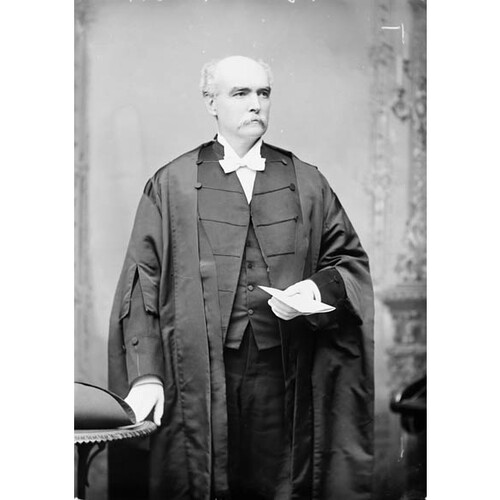

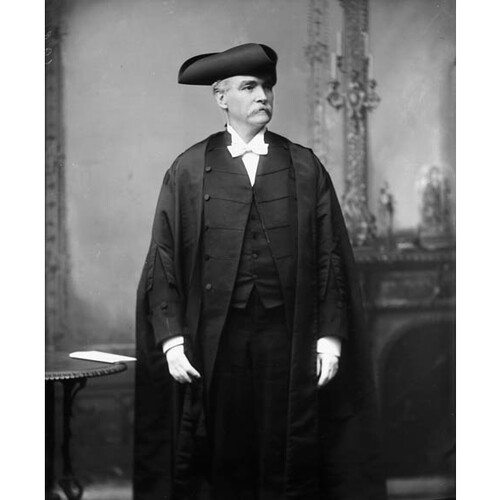

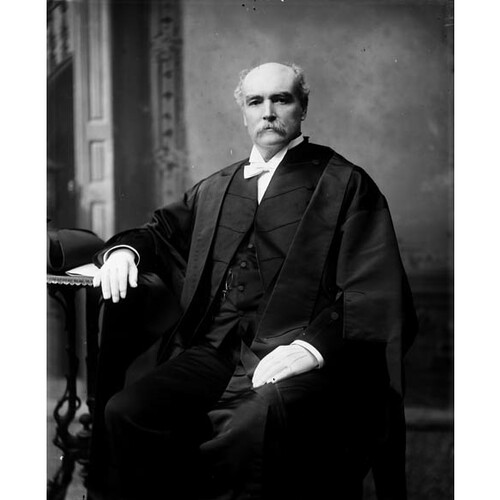

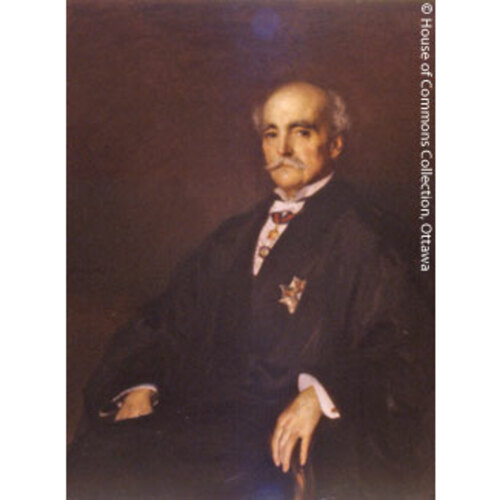

Despite this initiative and his record of service to the Liberal party, Edgar was not included in Laurier’s cabinet in 1896. Instead, the prime minister appointed him speaker of the House of Commons, a position Edgar would hold until his death. It was the first of the honours that were bestowed upon him in the final years of his life. In recognition of his volumes of poetry, The white stone canoe: a legend of the Ottawas (Toronto, 1885) and This Canada of ours, and other poems (Toronto, 1893), he was elected to the Royal Society of Canada in 1897. His last work, Canada and its capital, was a series of patriotic but rather turgid sketches of political and social life in Ottawa. In 1898 he was made a kcmg, despite his long-held opposition to Canadians accepting imperial titles. His health, however, had been in steady decline since the beginning of the decade – he suffered from Bright’s disease – and on 31 July 1899 he passed away. He had been a “strong party man,” Laurier told the commons, a tribute which aptly summed up Edgar’s service to Canada.

In addition to the works named in the text, James David Edgar’s publications include “A potlatch among our West Coast Indians” and “Celestial America,” both in Canadian Monthly and National Rev. (Toronto), 6 (July–December 1874): 93–99 and 389–97; A protest against the increased taxation advocated by the Canadian opposition as their National Policy, being an address to the electors of Monck (Toronto, 1878); The commercial independence of Canada; an address . . . (Toronto, [1883?]); Loyalty; an address delivered to the Toronto Young Men’s Liberal Club, January 19th, 1885 ([Toronto, 1885]); and The Wiman–Edgar letters: unrestricted reciprocity as distinguished from commercial union; first letter – Mr. Edgar to Mr. Wiman (n. p., 1887). Other writings are listed in Canadiana, 1867–1900 and CIHM Reg.

AO, MS 20; MU 960–70. NA, MG 26, B; G. UTFL, ms coll. 110 (John Charlton papers). Canadian biog. dict. CPC, 1873. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.2. A dictionary of Scottish emigrants to Canada before confederation, comp. Donald Whyte (Toronto, 1986). Dominion annual reg., 1882: 171, 411; 1883: 205, 390; 1884: 344, 391. Encyclopedia of music in Canada (Kallmann et al.), 226. B. P. N. Beaven, “A last hurrah: studies in Liberal party development and ideology in Ontario, 1875–1893” (phd thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1982). [O.] P. Edgar, Across my path, ed. Northrop Frye (Toronto, 1952). E. V. Jackson, “The organization of the Canadian Liberal party, 1867–1896, with particular reference to Ontario” (ma thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1962). R. M. Stamp, “The public career of Sir James David Edgar” (ma thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1962). P. D. Stevens, “Laurier and the Liberal party in Ontario, 1887–1911” (phd thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1966). Waite, Canada, 1874–96. R. M. Stamp, “J. D. Edgar and the Liberal party: 1867–96,” CHR, 45 (1964): 93–115.

Cite This Article

Paul Stevens, “EDGAR, Sir JAMES DAVID,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/edgar_james_david_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/edgar_james_david_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Paul Stevens |

| Title of Article: | EDGAR, Sir JAMES DAVID |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | December 20, 2025 |