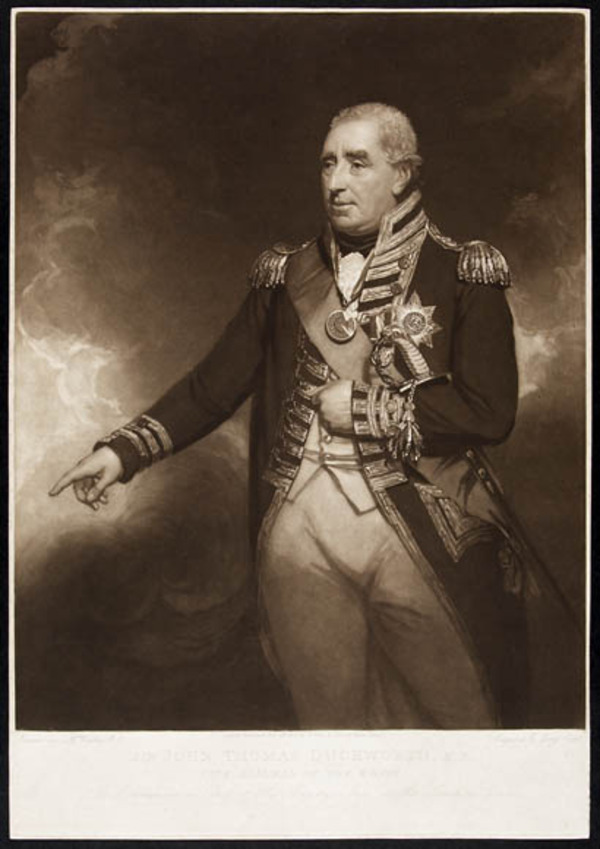

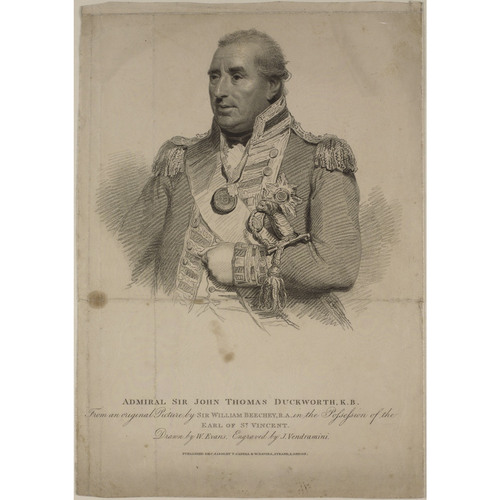

DUCKWORTH, Sir JOHN THOMAS, naval officer and governor of Newfoundland; b. 9 Feb. 1747/48 in Leatherhead, England, son of the Reverend Henry Duckworth and Sarah Johnson; m. July 1776 Anne Wallis, only child and heiress of John Wallis of Camelford, England, and they had one son and one daughter; m. secondly 14 May 1808 Susannah Catherine Buller, daughter of William Buller, bishop of Exeter, and they had two sons; d. 31 Aug. 1817 in Plymouth, England.

Descended from an old landed family, John Thomas Duckworth went to Eton College as a young boy but at the age of 11, on the invitation of Edward Boscawen*, decided to join the Royal Navy. He entered Boscawen’s ship of the line Namur on 24 July 1759 at Portsmouth. After serving in it and in the Prince of Orange, he joined on 5 April 1764 the 50-gun Guernsey at Chatham. The Guernsey was the flagship of Commodore Hugh Palliser*, the newly appointed governor of Newfoundland, so it was as a young midshipman that Duckworth first saw the island to which he was to return to govern half a century later. He spent two happy and instructive years in the Guernsey: Palliser was one of the ablest of the 18th-century governors of Newfoundland, Joseph Gilbert, an accomplished chart-maker, was master of the Guernsey, and Michael Lane, who was to follow James Cook* as surveyor of Newfoundland, was the schoolmaster in the ship.

Duckworth passed his lieutenant’s examinations on 13 May 1766 and was confirmed in that rank on 14 Nov. 1771. With the outbreak of the American revolution, he saw action in North America and the West Indies as first lieutenant in the frigate Diamond. On 16 June 1780 he was promoted captain and soon afterwards became flag-captain to the admiral of the West Indies squadron, Sir George Brydges Rodney, in the Princess Royal. After a period “on the beach” between wars, he was appointed in 1793 commander of the 74-gun Orion in the Channel fleet of Admiral Lord Howe, and took part in the victory over the French fleet off Ushant on the “Glorious First of June,” 1794. In the following years of the long war, Duckworth commanded ships and squadrons in home waters, the West Indies, and the Mediterranean. In April 1800 he intercepted a large and rich Spanish convoy off Cadiz, and his share of the prize money was said to have been £75,000. The following year he was knighted. He was commander-in-chief on the Jamaica station from 1803 to 1805 and was appointed vice-admiral on 23 April 1804. Early in 1806 Duckworth was engaged in a blockade of Cadiz, which he broke off to pursue a French squadron across the Atlantic to the Leeward Islands and destroy it off San Domingo (Hispaniola) on 6 February. He received the thanks of both houses of parliament, a yearly pension of £1,000 from the House of Commons, and the freedom of the City of London. The following year he took a squadron into the Dardanelles with peace terms for the Sublime Porte, but through no fault of his own had to return without reaching Constantinople (Istanbul) or contacting the Turkish potentate.

On 26 March 1810 Duckworth was appointed governor of Newfoundland and commander-in-chief of the squadron there. Nearing the end of along career, wealthy, and but recently remarried, he seems to have hesitated about taking the command of a relatively minor squadron on a rather remote station. The appointment was sweetened by promotion to full admiral, and in his flagship, the 50-gun Antelope, he reached St John’s harbour on 9 July after a “very tedious passage” of 27 days. At this time the Newfoundland command included, besides the great island itself, the coast of Labrador, Anticosti Island, and the captured French islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon. Duckworth’s frigates, sloops, and schooners were dispersed widely throughout this domain, patrolling the seas from Davis Strait to the Gulf of St Lawrence. The governor himself remained in St John’s, except for a tour of the northern outports of Newfoundland and the southern coast of Labrador in August 1810, the first such visitation in 30 years.

Newfoundland was in the throes of transition from a summer fishing settlement to a permanently settled colony and Duckworth had to preside over this process as best he could. The island had a population of some 30,000, largely concentrated on the shores of the eastern bays and the Avalon peninsula, with about 7,000 of them in the ancient capital of St John’s. Although the once mighty migratory fishery was rapidly dwindling, the antiquated anti-settlement laws remained formally in effect, and Newfoundland lacked many of the institutions of a settled country. The governor, for example, still stayed only for the summer, and ruled without the mixed benefits of advisory council and elected house of assembly. The home government was, however, beginning to face the realities of change, and in 1811 parliament passed legislation allowing fishing ships’ rooms in St John’s harbour to be converted into private property. Duckworth had the designated lands surveyed and let at public auction in renewable leases of 30 years, on condition that the buildings erected be in stone or brick, that streets be of an ample width, and that adequate sewers be built [see Thomas George William Eaststaff*]. He proposed that the annual rentals be devoted to the “most essential wants” of Newfoundland, which to his mind were better magistrates and more missionaries.

By 1812 Duckworth recognized that the old laws favouring the migratory fishery were now obsolete – “it is no longer a question of preference between two systems, that which was justly the favourite is now no more.” However, he did not believe that a full colonial government with a legislature was either necessary or desired by the inhabitants, and he strongly opposed handing over powers to the increasingly vocal St John’s élite of merchants and professional men. Dr William Carson* became particularly obnoxious to Duckworth, with his pamphlets attacking the governor’s arbitrary powers and calling for an elected local legislature. Sir John denounced the pamphlets as indecent and libellous and enforced his “peremptory determination” not to reappoint Carson as surgeon to the Loyal Volunteers of St John’s, the local militia unit.

On the other hand Duckworth helped to plant and nurture some of the institutions essential to a civilized society. He took a great interest in the building and repair of churches, from Twillingate on the northeast coast round to the Burin peninsula and Fortune Bay on the south coast. The Anglican church in St John’s especially engaged his attention. Since the pews were all rented out, his soldiers and seamen had to stand in the aisles and poor people were completely excluded. A government grant of £250 was paid in 1812 after the church had been repaired and enlarged according to his wishes. He pressed the archbishop of Canterbury to send out more missionaries, for whom government allowances and pensions were available, and recruited some from Devon, where he made his home. Duckworth worked with the Reverend Lewis Amadeus Anspach* to improve the rudimentary school system. In 1811 he readily accepted the proposal that a public hospital be built in St John’s, financed by subscriptions from the merchants and “very moderate” assessments imposed on the fishermen and seamen of the port.

Of all the Newfoundland governors, Duckworth made the most persistent attempts to rescue the Beothuk Indians from oblivion. As soon as he arrived in 1810, he issued proclamations ordering the Micmacs, the Inuit, and the white population to treat the Beothuks with kindness. A reward of £100 was offered to anyone who established friendly contact on a continuing basis. In October he ordered Lieutenant David Buchan* to sail north to the Exploits River, anchor his schooner the Adonis there for the winter, and “proceed to discover the haunt of the Native Indians.” Buchan did reach the interior wigwams of the elusive natives but had to withdraw after the unfortunate murder of two marines. The governor reported home that although the enterprise had ended in tragedy, the zeal and manly endurance shown was worthy of better success. He readily gave his lieutenant permission to winter in Newfoundland, the better to resume the search the following spring.

In 1812, however, the outbreak of war with the United States cut short the well-intentioned enterprise. Duckworth arrived in St John’s on 16 July to find the townspeople in a state of alarm, anticipating an American descent. He immediately cancelled his projected trip to the south coast, ordered all his warships to sea to patrol the coasts, and tried to put the capital itself in defensible condition. With the aid of a citizens’ committee of defence, he revived and enlarged the militia force, which was renamed the St John’s Volunteer Rangers, and which came to comprise over 500 well-trained officers and men. He strengthened the seaward defences of the town and established a signal station on a nearby promontory to warn of the approach of enemy ships. In outports up and down the coast the residents formed themselves into companies and laboured, under the guidance of officers sent with warships bearing ordnance supplies from St John’s, to erect gun batteries able to beat off privateers. Although American privateers swarmed in Newfoundland waters, only a few communities were attacked, and the royal ships themselves captured a goodly number of the marauders. When Duckworth left Newfoundland for the last time at the end of October, the leading merchants and inhabitants of St John’s, with the notable exception of Dr Carson, presented a farewell address thanking him for the measures taken to protect the trade and fisheries in general and St John’s in particular.

However successful his tenure as governor had been, Duckworth had no wish to prolong it, and on 2 Dec. 1812, barely a week after arriving home, he tendered his resignation, after being offered a parliamentary seat for New Romney, on the Kent coast. He was created a baronet on 2 Nov. 1813 and in January 1815 was appointed commander-in-chief at Plymouth naval base, where he died in August 1817. The body was brought back to Wear House, his country seat on the Devon coast, and the funeral took place on the afternoon of 9 September in Topsham church. He was laid to rest in the family vault, in a coffin covered with crimson velvet studded with 2,500 silvered nails.

Duckworth’s career was distinguished but at times controversial. To some contemporaries he was a generous and brave man and a skilful naval officer, although others accused him of being selfish and of lacking decisiveness. As governor of Newfoundland he seems to have been capable. He sought the best and most impartial advice on problems of the day, reported to the home government promptly and thoroughly, and displayed real energy and resolve in the crisis of 1812. He saw clearly that the migratory fishery was finished and that the future lay with the settlers for whom the island had become home, but he did not so clearly see that they must inevitably desire to govern themselves. It is not unfitting that a major thoroughfare in St John’s bears the name of the governor who helped lay some of the foundations of the modern city.

[Sir John Thomas Duckworth’s career, especially as governor of Newfoundland, is well documented by a mass of papers in several repositories. His Newfoundland station papers were preserved in private hands and in 1970, through the efforts of the then premier of Newfoundland, Joseph Roberts Smallwood, they were purchased for the PANL, where they became P1/5, Duckworth papers, files 1–24. Correspondence of Duckworth as governor of Newfoundland is also found in the letterbooks of the Department of the Colonial Secretary (PANL, GN 2/1, 21–24). Dispatches from Newfoundland to the Colonial Office and Admiralty are in the PRO in CO 194/49–53 and ADM 1/477. Duckworth’s admiral’s journal from 1810 to 1812 is in ADM 50/73 and should be studied in conjunction with the log of his flagship Antelope between 1809 and 1813, which is in ADM 51/2123. His will is in PRO, PROB 11/1598/570.

The National Maritime Museum (London) has an important collection of Duckworth papers (DUC/1–46); DUC/16–18 contains Newfoundland squadron papers, 1810–12, and DUC/30 is Duckworth’s official letterbook for 1812. Yale Univ. Library, Beinecke Rare Book and ms Library (New Haven, Conn.), Osborn coll., has account books, letterbooks, order-books, and correspondence for the period 1790–1817, and another series of Duckworth items beginning in 1785. The Univ. of Chicago Library has Newfoundland papers of Duckworth, especially those dealing with American fishing rights and issues raised by the War of 1812. There is a small but interesting collection of Duckworth manuscripts, largely of a family nature, in QUA. In 1977 the PAC produced a microfilm collection of Duckworth papers, integrating the small collection of PAC originals with the papers in the PANL and QUA, and adding selections from the National Maritime Museum material (PAC, MG 24, A45). Since then the Univ. of Chicago papers have been added.

Printed material on Duckworth, especially for the Newfoundland years, is relatively scanty, and there is no full-scale biography. Biographical accounts in dictionaries are reasonably full, except for the Newfoundland period. The DNB has the best balanced account. The life in James Ralfe, The naval biography of Great Britain . . . (4v., London, 1828), 2: 283–301, is unreliable and incomplete on several points. It is based largely on an obituary in Gentleman’s Magazine, July–December 1817: 275, 372–74. Another obituary appeared in Naval Chronicle, 38 (July–December 1817): 262–64, which had earlier printed a “Biographical memoir of Sir John T. Duckworth, K.B. . . .” in vo1.18 (July–December 1807): 1–27.

For Duckworth in Newfoundland the following general histories are of use: L. A. Anspach, A history of the island of Newfoundland . . . (London, 1819); The Cambridge history of the British empire (8v., Cambridge, Eng., 1929–59), vo1.6; Joseph Hatton and Moses Harvey, Newfoundland: its history, its present condition, and its prospects in the future (Boston, 1883); Paul O’Neill, The story of St. John’s, Newfoundland (2v., Erin, Ont., 1975–76); Charles Pedley, The history of Newfoundland from the earliest times to the year 1860 (London, 1863); Prowse, Hist. of Nfld. (1895). The PANL published [L. A. Anspach], Duckworth’s Newfoundland: notes from a report to Governor Duckworth by Rev. Louis Amadeus Anspach ([St John’s, 1971]). See also the Royal Gazette and Newfoundland Advertiser (St John’s), 1810–12, for notices of official ceremonies, addresses, and proclamations. w.h.w.]

Cite This Article

William H. Whiteley, “DUCKWORTH, Sir JOHN THOMAS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 12, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/duckworth_john_thomas_5E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/duckworth_john_thomas_5E.html |

| Author of Article: | William H. Whiteley |

| Title of Article: | DUCKWORTH, Sir JOHN THOMAS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1983 |

| Year of revision: | 1983 |

| Access Date: | December 12, 2025 |