Source: Link

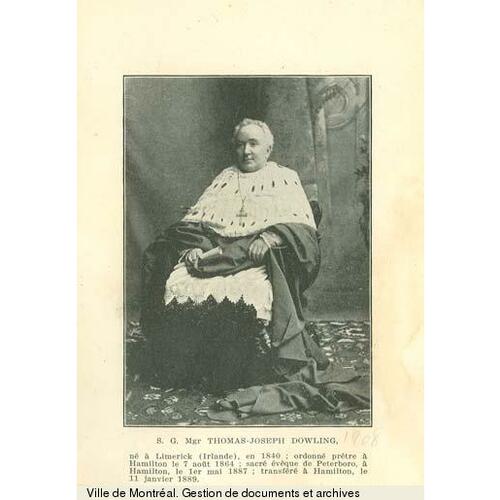

DOWLING, THOMAS JOSEPH, Roman Catholic priest and bishop; b. 28 Feb. 1840 in Shanagolden (Republic of Ireland), son of Martin Dowling; d. 6 Aug. 1924 in Hamilton, Ont.

Thomas J. Dowling immigrated from Ireland to Hamilton with his family in 1851. He attended a “select school” there and then went to St Michael’s College in Toronto, where he studied under famed Basilian orator Michael Joseph Ferguson and excelled in public speaking and literature. After further study at the Grand Séminaire de Montréal, he was ordained at St Mary’s Cathedral in Hamilton on 7 Aug. 1864 by Bishop John Farrell*. Dowling’s initial posting within the Hamilton diocese, in October, was to a large mission area based in Paris, where he quickly displayed talents as a builder priest and orator of note. To retire the debt on the uncompleted church in Paris, he went on a successful lecture and fund-raising tour that included Chicago and Pennsylvania.

In 1881 he became the diocese’s vicar general. As such, he acted as interregnal administrator between the death in 1882 of Farrell’s successor, Peter Francis Crinnon, and the appointment in 1883 of James Joseph Carbery. On 29 Jan. 1884 Dowling was honoured as diocesan administrator at a banquet given in Paris by his fellow clergymen, whose gift, a purse of $500, he put into the building fund of his church.

In December 1886 Dowling was elected to succeed Jean-François Jamot* as bishop of Peterborough. Consecrated in Hamilton on 1 May 1887, he proceeded to develop the policies that would define his episcopal career: a commitment to the physical development of the church, a willingness to travel, and a recognition of the needs of non-English-speaking Catholics. Despite the vastness of his diocese, which stretched to the Manitoba border, Dowling in a very short episcopate managed to visit Sudbury, Sault Ste Marie, and the Lakehead. He provided full-time priests for his diocese’s many French-speaking communities and ensured that, at Christmas and Easter, priests fluent in Dutch, German, and Italian were made available to parishes where these were the first languages of significant numbers.

Following the death of Carbery in December 1887, rumours circulated that Dowling’s Hamilton upbringing made him the logical successor. As was customary, he denied any interest. However, when the Vatican announced that he would indeed be Hamilton’s fourth bishop, he admitted, “It is a consolation for me to know that I am not a stranger to the diocese, that I am returning, as it were, to the home of my childhood, amongst kind and esteemed friends of the clergy and laity.” He was transferred to Hamilton on 11 Jan. 1889 and installed on 2 May.

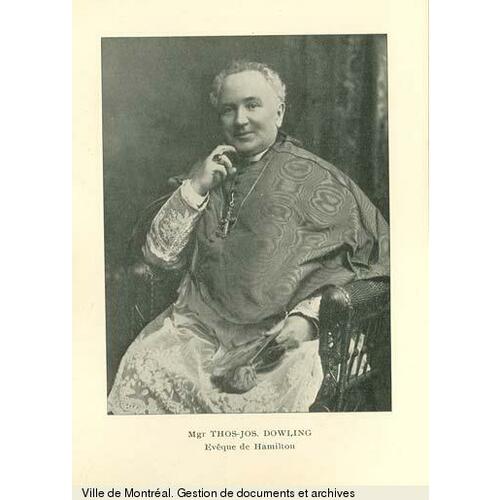

During his episcopate in Hamilton, Dowling continued his attention to the physical expansion of the church. Within two years he had arranged for the building of six churches, three convents, and nine schools and for the enlargement of an orphanage. In addition, he exhibited characteristics which differentiated him from his fellow bishops, several of whom remained aloof from both their clergy and their flock. At the time of his appointment one correspondent spoke of “his truly brotherly regard for his fellow priests . . . and thoroughly conscientious fulfillment of his pastoral duties.” It was especially his relationship with the laity that set Dowling apart. Highly sociable – photographs reveal an open, round face, a high forehead, and tousled hair – he was a poet and a singer. His verse, original if not always distinguished, was readily offered, often in congratulatory form at farewells, priestly anniversaries, baptisms, and weddings. At funerals for priests and nuns there would be lamentations, eulogies, or both. As a singer, Dowling regularly performed at concerts in schools and St Joseph’s Orphanage in Hamilton, and without fail at St Patrick’s Day festivities. Newspaper accounts indicate that he expected to be called upon on such occasions; when he was not, he openly expressed disappointment.

Dowling’s reaction to the massive influx of immigrants that had begun in the 1890s paralleled episcopal response in some other large urban centres. Much like Fergus Patrick McEvay* in Toronto, he argued it was the responsibility of the church to provide services in the language of the foreigners. He consequently arranged such services for Germans, Italians, and Poles. The Germans in Waterloo County and the Walkerton-Hanover area were the easiest to satisfy. His initial action was to issue a blanket celebret to Father Louis G. F. H. Funcken, superior of the Congregation of the Resurrection in Berlin (Kitchener), who was sent to Europe to recruit German-speaking priests. The long-term solution was closer to home: St Jerome’s College, run by the Congregation, became a source of native-born, German-speaking clergy. Hamilton’s growing Italian community was similarly well served: in 1908 St Anthony of Padua parish was established in the city’s east end. Five years later Dowling called on the Italians of Guelph, going so far as to visit the homes of prominent members of the community and converse through a translator. By 1922 the Italian population there was sufficiently large that a separate parish had been created.

The Poles were more problematic, though the Resurrectionists, who had been founded to minister to Polish émigrés in France, had laid some groundwork. The problems included rivalries within the Congregation, fears that a schism among Polish American Catholics might be repeated in Canada, traditional linkages between Polish nationalism and Catholicism, and the opposition of some priests to ethnically based Polish parishes. Despite such pressures, Dowling acceded to requests from Polish communities. In 1911 a lot was allocated at Barton and St Ann streets in Hamilton for St Stanislaus Church. A year later Sacred Heart parish in Berlin was opened. Less successful were Dowling’s efforts to service the non-Latin-rite faithful in Berlin and Owen Sound. There was difficulty finding priests for them and those who arrived left, complaining of the antagonism of the local Latin-rite pastors.

Given his background, Dowling had always been drawn to Irish politics and Irish perspectives in Canada. He fully embraced the idea of a distinctive Canadian identity expressed by Thomas D’Arcy McGee*. As a parish priest in Paris in 1866, Dowling made his opinions of the Fenians abundantly clear by acting as a chaplain for the local militia. A firm believer in the work of Daniel O’Connell, the Irish leader who had favoured constitutional solutions, he spoke frequently on Irish affairs and contributed to the Irish Canadian (Toronto). Though he recognized that the Irish in Canada were better off than those at home, he joined Archbishop John Joseph Lynch* of Toronto and other prelates in discouraging “improvident emigration” to urban areas. Hamilton’s Irish ghetto, which existed literally in the shadow of St Mary’s Cathedral, was a constant reminder of what could go wrong.

In an attempt to separate partisan and religious affairs, Dowling made the necessary disclaimer in 1889 that he was “above and beyond the sphere of politics.” Still, though he may have been less obvious than some of his more flamboyant episcopal colleagues, he quietly wielded considerable power. In 1888 he had approached Lynch with a request that Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald* be asked to ensure that the “right” candidate received a judicial appointment. He advised Lynch to inform Macdonald that here was an “opportunity . . . of conciliating a young bishop whose people form his balance of power in several doubtful constituencies.” Dowling himself intervened for the Tories in Northumberland County in 1887 and in Haldimand County in 1895. In addition, his advice was sought over the Jesuits’ Estates Act and the Manitoba school question. When these controversial issues caused influential Conservative spokesman D’Alton McCarthy* to go his own way and divide the party, Macdonald asked Dowling to explain to Catholics that the renegade’s views were not sanctioned by the Tory hierarchy. In February 1891 the prime minister encouraged Dowling to urge his parish priests to sermonize on the evils of unrestricted reciprocity, which could lead to annexation by the United States and reduced rights for Canadian Catholics.

After Macdonald’s death in June, Dowling sustained his affiliation with the Conservatives. He was especially pleased at their choice as leader in 1892 of John Sparrow David Thompson*, a Catholic and an ally of Bishop John Cameron* of Antigonish, N.S. Dowling even found it possible to forge an alliance with Mackenzie Bowell*, Thompson’s successor and a former grand master of the Orange order, but there is no evidence that the affiliation continued through the short-lived prime ministership of Sir Charles Tupper*. At the same time it does not appear that Dowling’s support shifted to the Liberal government of fellow-Catholic Wilfrid Laurier*. Their relationship was somewhat limited and formal. It was not until Laurier’s defeat 15 years later by Conservative Robert Laird Borden* that Dowling renewed his requests for federal placements for Catholics.

Provincially Dowling’s political involvement was less predictable. In the 1880s he had readily joined Lynch and Bishop James Vincent Cleary* of Kingston in supporting the Liberals of Oliver Mowat* and opposing the “no popery” policies of the Conservatives under William Ralph Meredith. Relations between the episcopal hierarchy and Mowat’s successors declined, however, after his departure for federal politics in 1896. Arthur Sturgis Hardy* was thought by Dowling to have snubbed him by not paying a call during a visit to Hamilton. Under George William Ross* the relationship deteriorated further: in 1900 Dowling complained that patronage positions in the Hamilton area originally designed as “Catholic” were being given to Protestants. By 1905, largely in response to scandals surrounding the Ross government, he had joined with other members of the hierarchy in support of James Pliny Whitney*’s Conservatives.

Like his episcopal counterparts, Dowling was a strong champion of separate schools, though somewhat more modernistic in his approach. A supporter in 1888 of Lynch’s opposition to the introduction of the secret ballot in school board elections, by 1894, despite continuing episcopal resistance, he recognized the inevitability of such change. Similarly, while others resisted expansion of separate secondary schools beyond fifth form, in 1916 Dowling thought it necessary that Catholic students should have the same opportunities as their peers in the public system and that the extra education was necessary to train Catholic teachers. He was also supportive of the general education offered by the Toronto-based Catholic Church Extension Society [see Alfred Edward Burke]. When other bishops questioned the society’s effectiveness, Dowling helped ensure its survival by encouraging Toronto archbishop Neil McNeil* and possibly donating money.

The bishop of Hamilton had displayed some tolerance in the controversy over French schools in Manitoba; he believed that a compromise solution would enhance the position of separate schools in Ontario. He would go no further, however, refusing in 1896 to join his Quebec colleagues in protest over Laurier’s compromise with Manitoba premier Thomas Greenway*. On the other hand, in the dispute surrounding Ontario’s Regulation 17 of 1912, which restricted the use of French in schools and divided the hierarchy, Dowling attempted to preserve the links with the French-speaking bishops and thus reduce the division, but he was overridden by Michael Francis Fallon*, the bishop of London, and others.

Dowling presided as prelate until his death in 1924. It was reported then that he had turned down the archbishopric of Toronto three times; certainly in 1898 he had rejected the chance to succeed John Walsh*. In 1914, after 50 years as a priest and 25 as a bishop, he was honoured with appointment as assistant bishop at the pontifical throne and domestic prelate.

After 1914 Dowling’s pace slowed considerably. By 1920 his ill health was acknowledged: the diocese was being run by an administrator and episcopal functions such as confirmation were being performed by missionary bishops. When Dowling died, on the eve of the 60th anniversary of his ordination, he was North America’s oldest active bishop. Although his work had been less public than that of some colleagues, it is clear that he was both a builder priest and, until his health failed, an excellent administrator. His greatest legacy was his recognition that, with the influx of non-anglophone immigrants after the turn of the century, the church in English-speaking Canada, so long Hibernian in nature, had to change to survive.

Arch. of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto, L (Lynch papers); MN (McNeil papers). Arch. of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Hamilton, Ont., T. J. Dowling papers; Dowling scrapbook. Arch. of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Peterborough, Ont., T. J. Dowling papers. LAC, MG 26, A, Macdonald to Dowling, 16 Dec. 1887; Dowling to Macdonald, 28 March 1889. Catholic Record (London, Ont.), 1884–1924, esp. 16 Aug. 1924. Catholic Weekly Review (Toronto), 5 May 1887. Hamilton Spectator, 7 Aug. 1924. Paris Star (Paris, [Ont.]), 19 July 1866. Edgar Boland, From the pioneers to the seventies: a history of the diocese of Peterborough, 1882–1975 (Peterborough, 1976). Alex Bros, “Polish immigrant relations with the Roman Catholic Church in urban Ontario, 1896–1923” (ma thesis, Wilfrid Laurier Univ., Waterloo, Ont., 1986). Canadian album (Cochrane and Hopkins), 1: 310. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.1. DHB, vol.2. Ken Foyster, Anniversary reflections: 1856–1981; a history of Hamilton diocese (Hamilton, [1982]). Marjorie Freeman Campbell, A mountain and a city: the story of Hamilton (Toronto and Montreal, 1966). Theobald Spetz, The Catholic Church in Waterloo County . . . ([Toronto], 1916). G. J. Stortz, “Thomas Joseph Dowling, the first ‘Canadian’ bishop of Hamilton, 1889–1924,” CCHA, Hist. studies, 54 (1987): 93–107.

Cite This Article

Gerald J. Stortz, “DOWLING, THOMAS JOSEPH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 17, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dowling_thomas_joseph_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dowling_thomas_joseph_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Gerald J. Stortz |

| Title of Article: | DOWLING, THOMAS JOSEPH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 17, 2025 |