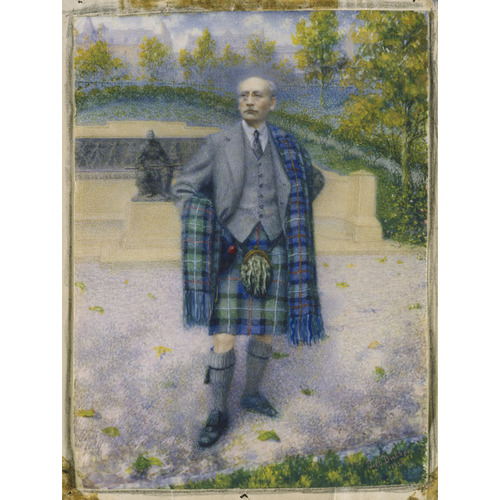

![Description English: R. Tait McKenzie Bain News Service,, publisher. R. Tait McKenzie [between ca. 1910 and ca. 1915] 1 negative : glass ; 5 x 7 in. or smaller. Notes: Title from unverified data provided by the Bain News Service on the negatives or caption cards. Forms part of: George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress). Format: Glass negatives. Rights Info: No known restrictions on publication. Repository: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print General information about the Bain Collection is available at hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.ggbain Persistent URL: hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ggbain.15688 Call Number: LC-B2- 3014-2 Date 29 October 2010(2010-10-29) (first version); 29 October 2010(2010-10-29) (last version) Source Transferred from en.wikipedia; transferred to Commons by User:Gerardus using CommonsHelper Original title: Description English: R. Tait McKenzie Bain News Service,, publisher. R. Tait McKenzie [between ca. 1910 and ca. 1915] 1 negative : glass ; 5 x 7 in. or smaller. Notes: Title from unverified data provided by the Bain News Service on the negatives or caption cards. Forms part of: George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress). Format: Glass negatives. Rights Info: No known restrictions on publication. Repository: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print General information about the Bain Collection is available at hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.ggbain Persistent URL: hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ggbain.15688 Call Number: LC-B2- 3014-2 Date 29 October 2010(2010-10-29) (first version); 29 October 2010(2010-10-29) (last version) Source Transferred from en.wikipedia; transferred to Commons by User:Gerardus using CommonsHelper](/bioimages/w600.2348.jpg)

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

McKENZIE, ROBERT TAIT, educator, physician, author, and sculptor; b. 26 May 1867 in Ramsay Township, Upper Canada, third child of William McKenzie and Catherine Shiells; m. 18 Aug. 1907 Ethel O’Neil (d. 1952) in Dublin; they had no children; d. 28 April 1938 in Philadelphia.

Robert Tait McKenzie’s father, a Free Presbyterian minister, emigrated from Edinburgh in 1857. About a year later his Scottish bride joined him in Ramsay, near Almonte in the Ottawa valley. In 1868 the family moved into town, where Robert went to high school. He then attended the Ottawa Collegiate Institute, took drawing lessons, and in 1885 entered McGill University in Montreal. There, initiated by his boyhood pal James Naismith, the wiry youth became enthralled with gymnastics; he would go on to win the university’s all-round gymnastics championship in 1889. He also participated in swimming, fencing, boxing, football, and track, and became the Canadian intercollegiate high-jump champion. Summers during his university studies were spent working on surveys in the Canadian west (where he also sketched), in the lumber camps of his uncle John Bertram*, and on Montreal’s docks. In 1889 he received his ba and entered McGill’s medical school. The next year he became the university’s gymnastics instructor; he had prepared for the job by enrolling in summer courses in physical education at Harvard University. He took to the new field of physical culture [see Henri-Thomas Scott*], especially sport and conditioning (for health and moral benefits) and related education.

Graduation (md, cm 1892) with a specialization in orthopaedics led two years later to positions in anatomy and physical instruction at McGill, his first published articles on physical education, and private and hospital practices. Among his patients were members of the family of Governor General Lord Aberdeen [Hamilton-Gordon], an association with advantages. On occasion McKenzie displayed his familial Scottishness, including his mastery of the chanter. During his time in Montreal he came to know fellow physicians William Osler* and Andrew Macphail as well as figures in the city’s artistic and literary circles, such as William Henry Drummond*, Charles Blair Gordon, and Arthur John Arbuthnott Stringer. At McGill the zealous doctor called for a new gymnasium and proposed radical plans to regulate athletic activity, give medical examinations to new students, and use exercise to counter what were termed “disease-producing conditions” in urban schools. Foreshadowing his professional progression, in an 1894 article he censured the emphasis on winning over recreation in American collegiate football. Though restricted by finances, McGill sanctioned his appointment – the first of its kind in Canada – as medical director of physical training in 1894. He also taught artistic anatomy and exhibited his sketches at the Art Association of Montreal. Influenced by sculptors George William Hill and Louis-Philippe Hébert*, who introduced him to the technique of relief and the ideas of historical romanticism, he ventured into creating models around 1900, probably with some familiarity with the genre of sport in American art. Like other realists in sculpture, he accepted the figure and neoclassical form, not aesthetic investigation, as his bases.

Papers begun by McKenzie in 1899 on strain in an athlete’s face led in 1902 to sculpted masks showing the progress of fatigue. At the same time, with an anatomical bent he started using the measurements of top athletes – an artistic misstep to some of his sculptor friends – as anthropometric guidelines to sculpt the idealistically calibrated figure, termed the “mathematical man.” Sprinter (1902), his first work in the round, displayed the recently introduced crouching start; McKenzie was a constant student of sporting technique. Exhibited at the Paris Salon and the Royal Academy of Arts in London, Athlete (1903) combined anthropometry, his conservative synthesis of classical figures and current notions of Hellenism, and seemingly out-of-place locker-room-content – a grip dynamometer. The piece received no fanfare, but it marked McKenzie as a new spokesman on bodily dynamics in art.

The University of Pennsylvania first invited McKenzie to join its faculty in Philadelphia in 1899. Five years later, with prospects to implement his ideas at McGill still limited, he agreed to move there to become a professor in the medical faculty and director of the department of physical education, which was granted full-faculty status. Related attractions included the university’s new gymnasium and enlarged athletic field, which he saw as opportunities to showcase exercise and promote compulsory activity. Though Penn was a hotbed of alumni-controlled sport, McKenzie pushed his own gospel. All undergraduates were to undergo medical examination and take exercise. Well informed by his exhaustive studies, he broadened his reformist scope to include the playground movement [see Mabel Phoebe Peters*] and public-school hygiene.

The fastidious doctor, who made time to establish a practice in orthopaedics in Philadelphia, moved into the local elite on the strength of his academic status and effective networking. He joined the prestigious Philadelphia Sketch Club, where Thomas Eakins’s paintings of sporting males had broken ground. Aboard a ship to London he courted Ethel O’Neil, a talented music teacher born in Hamilton, Ont., and their subsequent marriage helped solidify his position in the city. The Aberdeens had assisted in arranging their wedding at Dublin Castle.

The environment and structures of big-time football that McKenzie found at Penn, including the subsidization of players, informed his art. Onslaught (1904–11), a pile of sprawling footballers, typified his facility with violent motion and captured the Ivy League spirit. Stories attest to his regard for the game, including his on-field medical missions, but his reservations about the politics of sports and insidious professionalism [see Francis Joseph Nelson; Norton Hervey Crow*] remained. His efforts to regulate some sports at the university (boxing, for instance) gained ground, just as his articles and speeches promoting amateurism and health, in American Physical Education Review (Boston) and elsewhere, carried weight. In total, he would publish over 100 articles in medical, educational, and art journals throughout his career.

In 1907 McKenzie assumed the professorship of physical therapy – the first such post in an American school. His Exercise in education and medicine (Philadelphia, 1909) would become an authoritative reference for physical educators. The recognition given McKenzie, including an honorary master of physical education degree from Springfield College, Mass., in 1914, came within the broader limitations of the time, not just sports politics. Women need physical training, he argued, but they are not meant for strenuous sport. Moreover, he declared during a summer lecture at the University of California in Berkeley in 1923, “over-indulgence in athletics is robbing the American girl of her beauty.” Claiming Greek antecedents which few questioned, he felt that, artistically, the male form held more intrinsic beauty. His rare renditions of the female were usually clothed or limited to faces; his negative opinions on women’s fashion, some on orthopaedic grounds, drew flak. Commenting on his exclusively male sculptures in a 1928 exhibition, along with an emotional range defined only by sport, a critic for the Toronto Daily Star would conclude, too harshly, that “McKenzie is no feminist.”

His surgeon’s hands served him well as he mastered relief portraiture and sporting scenes. Anatomical accuracy had to underlie every pose, every bulge of muscle. Most of McKenzie’s sport sculptures were nudes, one exception being Onslaught; his Belgian sculptor friend Charles van der Stappen had persuaded him it would be best if the footballers were fully clothed. McKenzie blended different methods from Greek sculpture of the high classical period (490–323 B.C.) to create his own ideal formation of the male figure. An association had started in 1910 with classicists Percy Gardner and Edward Norman Gardiner, whose now-outmoded writings on Greek sport and sculptural idealism lent cachet to McKenzie’s aims. His conservative instincts were also reinforced by his study of 19th-century American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. McKenzie’s figures were nevertheless intended to strike viewers as modern – in their display of more muscle than what is seen in classical nudes as well as in his choice of sport, irregular motion, and even hairstyles.

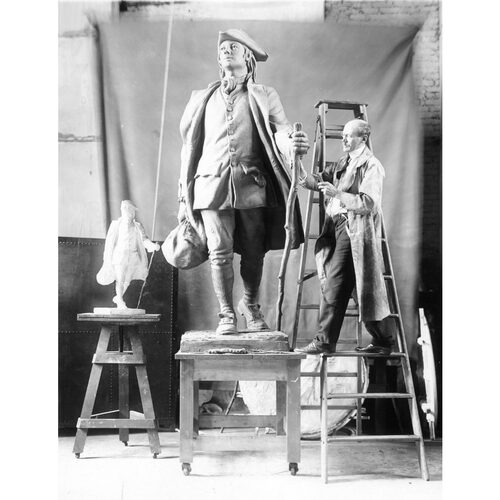

Reviews garnered by such reliefs as McKenzie’s Joy of effort, the large medallion of hurdlers commissioned in 1912 by the United States Olympic Committee, reflected the enthusiastic public response to his mounting register of exhibitions, commissions, and sales. His connection with the Olympics would be enduring: he first gave a series of lectures on artistic anatomy in connection with the 1904 Olympics, exhibited his sport sculpture at the 1924 and 1928 games, and won a bronze medal in the 1932 Olympic Art Competition. In all, using foundries in Providence, R.I., and New York City, this “indefatigable worker,” as British art historian William Kineton Parkes described him, produced some 126, mostly small-scale, works on sport. But reviews were mixed. His sculpture struck some critics as “unusual” or “skilful if not especially distinguished bits of modelling.” Though other sculptors of sport in the United States and Britain displayed more aesthetic and compositional complexity, few did as much to produce such popular icons. By 1910, building on his growing reputation, he had branched out into historical commemoration. A statue for Penn of its famed founder, Benjamin Franklin, was unveiled in 1914. Characteristically, McKenzie had pored through the sources on Franklin for inspiration and physical accuracy; not least, this quintessential American had been an advocate of exercise. One impressed alumnus recognized McKenzie’s yearning for “physical veracity” rather than the “emotional tension” characteristic of the work of Rodin.

World War I abruptly refocused McKenzie’s attentions. Despite his residence in the United States, he was still a British subject, and in 1915 he took a leave of absence from the university to go to England to join the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Instead, he accepted a temporary lieutenancy in July in the Royal Army Medical Corps. Initially refused an assignment at Britain’s physical-training headquarters because there were no openings, he enrolled in a basic-training course, during which the army discovered he was the author of one of their textbooks, Exercise in education and medicine. Soon assigned to the War Office, he helped to develop a new physical-training program and reorganize Britain’s convalescent camps. Promoted temporary major, he became commanding officer at the Heaton Park Command Depot, where he oversaw the treatment of thousands of wounded soldiers. More pioneering articles and texts on physical reconstruction, therapy, and rehabilitation followed between 1915 and 1923, including his groundbreaking Reclaiming the maimed: a handbook of physical therapy (New York, 1918), which would be used as the official rehabilitation manual of the United States navy and army as well as of the government of France. With the admitted aim of returning soldiers to service, he used electrotherapy, dry heat, and hydrotherapy to treat muscle, and recognized the need for psychiatric overlap. McKenzie also designed several apparatuses for physiotherapy. During his time at Heaton Park he had a high success rate in rehabilitating soldiers, with approximately half of his patients returning to military service. After relinquishing his commission in September 1916, McKenzie inspected convalescent facilities in Canada and the United States in 1917–18, but this was not the end of his engagement with wounded soldiers. His revulsion over bodily ruin fuelled his devotion to physical betterment and steered him away from any artistic depiction of hellishness in the trenches. By 1919, after going back to Penn, he had joined the faculty of the Philadelphia School of Occupational Therapy, which was founded that same year.

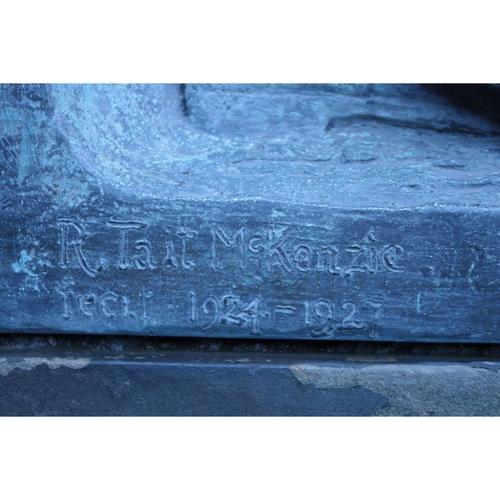

Busy to the point where he dropped his private practice, McKenzie was sought out in the post-war run to erect monuments in Britain, the United States, and Canada, where he longed for recognition. Feature articles boosted his notability. McGill would grant him an lld in 1921, and several planned projects resulted from his continued connections with Canadian dignitaries. His first Canadian memorial was erected in Montreal in 1919 to honour a son of Sir George Alexander Drummond*. Spurred by such commissions, McKenzie resumed exhibiting in 1920. In a show that year in London his athletic studies of young manhood drew praise for their emulation of old Greek sculptors, not so much for the modelling of the works as for their supposed spirit. From his reputation in Britain came his commission for a memory-shaping war monument in Cambridge (Home-coming, 1920–22), for which he researched the smooth faces and bodies of the brave East Anglian “racial type” he wanted to depict, an approach now questioned as pseudoscience. The antithesis of blasted flesh and the essence of hope, the figure is the visual equivalent of the youths of the famed war poets, such as Wilfred Owen and Rupert Brooke. The wrenching imagery of Charles Sargeant Jagger’s Royal Artillery monument (1923–25) in London was not for McKenzie. Next came his memorial in Almonte (The volunteer, 1921–23), again a sentimentalized young man in uniform (allegedly having a “disquieted soul within”), which brought McKenzie back to the Ottawa valley for the first time since his mother’s death in 1914. This sculpture was followed by a large memorial showing the transformation from civilian to soldier in Edinburgh (The call, 1924–27). Sponsored by the St Andrew’s Society of Philadelphia, it was considered by the artist to be his best work.

From these projects, which demanded patient negotiation with local committees and a sure grasp of post-war sentiment, it was an easy step to his romanticized statue (1927–30) of General James Wolfe* in Greenwich (London). His study of the work of Anglocentric historians and long tramps over the Plains of Abraham in Quebec City provided the heroic grounding he wanted. A member of the National Sculpture Society in the United States from 1922 and of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, in 1928 he was elected a fellow of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts. That same year he was awarded an honorary doctorate of fine arts by the University of Pennsylvania. Intensified exposure brought increased critical attention. In 1925 he was featured in International Studio (New York) in an article about a range of sculptors of athletes of both sexes. A 1928 show in Toronto, which juxtaposed the works of McKenzie and Paul Howard Manship, confirmed their mastery of muscle in motion, though the younger Manship had taken archaism to avant-garde levels.

For McKenzie, sculpture was nonetheless a lucrative and needed diversion from the ongoing rancour, especially after the war, between his department and the university’s independent athletic association. In lectures and articles, in which he incessantly promoted the education and physical performance of the average person, he railed against this rancorous division, the debilitating corporal effects of pushing developing boys into competition, subsidization, the lax handling of gate-moneys, and what he considered over-enthusiastic alumni. Though outmanoeuvred and outvoted for years, he had made progress in achieving his goals through the establishment of an instructorship in physical education for women (1919), an attempt by the university trustees to merge physical education and athletics (1922), a program for preparing physical-education teachers, and his many important textbooks and articles on physical education and therapy, his primary fields of sway. Overworked, in 1929 McKenzie, who had threatened resignation more than once, was given a year’s leave. A hagiographic biography that year by British art historian Christopher Hussey, who championed him as a “modern Phidias,” brought additional encouragement.

Inveterate travellers, he and his socialite wife went to the Mediterranean and Britain for a vacation in 1930. A friend wrote that he should take the opportunity to study genuine “Greek and Roman antiquity” to bolster his definition of “the laws of human male beauty.” McKenzie’s work was fully imbued with the homoeroticism deeply embedded in amateur-sport culture. Other commentators verified his preoccupation with early-20th-century perceptions of Greek ideals of male perfection, an interest that meshed with his enthusiasm for the Olympic movement and his ongoing rapport with Edward Gardiner, whose 1930 book on ancient athletics had cited McKenzie’s bronzes as parallels to its archaeological representation.

Revisiting his roots in search of a summer retreat, in 1931 he purchased a derelict mill near Almonte. Assisted by his architect nephew William O’Neil, he restored it, adding a studio and naming it the Mill of Kintail in honour of the McKenzies’ ancestral home in Scotland. It was a splendid backdrop for his sentimentalized Highlandism. Inspired by local historians, he collected artefacts and documents. Old acquaintances remembered him as a mild and intensely systematic man. Trips from Philadelphia became frequent, as did his contacts with Canada’s upper echelons; in 1932, at the unveiling of his confederation memorial in the centre block on Parliament Hill, the McKenzies stayed with Governor General Lord Bessborough [Ponsonby*]. That year he designed the Fields Medal (an international mathematics prize) for fellow Canadian John Charles Fields. In Ethel’s small volume of poetry (1932) she revered Tait’s tactility in clay. Further satisfaction came from his executive service with such organizations as the Academy of Physical Education and the Academy of Physical Medicine. At his university, following exposés by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching and a change of presidents, departmental reforms had been introduced in 1931 to restore amateurism in athletics and set up divisions of student health, physical education, and varsity sport that had student managers. In recognition of McKenzie’s advisory involvement, and to delay his full retirement, the university named him to the newly created J. William White Research Professorship of physical education.

The 1930s were crammed with sculptural commissions. Throughout his career he executed more than 200 works. Modern trends in art since the war, including primitivism (the borrowing of imagery from non-western peoples), attacks on what was termed “the burdensome weight of Greece,” and carving in stone held no interest for the self-assured McKenzie. There had been little evolution in his work; the repeated capture of commemorative and athletic moments concerned him more. His late years were rewarding, despite a heart condition, with his near hyperactivity in public offset by time in his studios.

In 1938 the Canadian House of Commons asked McKenzie to create a memorial for dominion archivist Sir Arthur George Doughty. McKenzie died suddenly that year of a heart attack at his home before he could complete the project. He had requested that his heart be buried in Edinburgh below his sculpture The call, but since city officials did not allow it, the organ was inhumed nearby in the yard of St Cuthbert Church; his ashes were interred at St Peter’s Episcopal Church in Philadelphia. Obituaries recognized his formative years in Canada and lauded his accomplishments in education and medicine, but some still found it difficult to evaluate his artistic worth. His “artistic, anatomical, and athletic interests were so closely connected,” one British biographer confessed, “that it is exceedingly difficult to form a just estimate of his rank as a sculptor.” The question is best weighed in balance with his wider achievements as a pioneer in the fields of physical education and therapy. Both competent and popular, McKenzie saw sculptural practice as the empirical science of understanding the body in the estimable state of athleticism, and he drew consistently upon the classical canon to give shape to a thoroughly contemporary idiom – the athletic American form.

For their assistance the author is grateful to Bruce Kidd, David J. Getsy, Marc Gotlieb, Stephanie Kolsters, Joyce Millar, Sarah O’Neil-Manion, and Jesse C. Roberts.

Robert Tait McKenzie’s publications, sculptures, and memberships are listed in J. S. McGill, The joy of effort: a biography of R. Tait McKenzie ([Toronto] and Bewdley, Ont., 1980). His war-related writings are considered in Fred Mason, “Sculpting soldiers and Reclaiming the maimed: R. Tait McKenzie’s work in the First World War period,” Canadian Bull. of Medical Hist. (Waterloo, Ont.), 27 (2010): 363–83.

LAC, R917-0-1. Mississippi Valley Conservation Authority, R. Tait McKenzie and James Naismith Museum (Almonte, Ont.), Museum and documentary coll. Univ. of Pa, Univ. Arch. and Records Center (Philadelphia), UPT50 MCK37. Almonte Gazette, 5 May 1938, 19 Jan. 1939. Evening Public Ledger (Philadelphia), 1915–21. Gazette (Montreal), 29 April 1938. Globe, 1920–28. London Gazette, 29 Oct. 1915, 19 Sept. 1916. New York Tribune, 1908–22. Toronto Daily Star, 1928–38. Art Gallery of Toronto, Catalogue of six exhibitions … ([Toronto, 1928]). Jean Barclay, In good hands: the history of the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy, 1894–1994 (Oxford, Eng., 1994). M. A. Budd, The sculpture machine: physical culture and body politics in the age of empire (New York, 1997). Melissa Debakis, Visualizing labor in American sculpture: monuments, manliness, and the work ethic, 1880–1935 (New York, 1999). A dictionary of Canadian artists, comp. C. S. MacDonald (8v., Ottawa, 1967–2006; vol.9 online only; all vols. available online in the “Artists in Canada” database at app.pch.gc.ca/application/aac-aic/description-about.app?lang=en). H. D. Eberlein, “R. Tait McKenzie, – physician and sculptor,” Century Magazine (New York), 97 (November 1918–April 1919): 249–57. Richard Elmore, “Sports in American sculpture,” International Studio (New York), 82 (October–December 1925): 98–101. E. W. Gerber, Innovators and institutions in physical education (Philadelphia, 1971). David Getsy, Body doubles: sculpture in Britain, 1877–1905 (New Haven, Conn., 2004). Christopher Hussey, Tait McKenzie: a sculptor of youth (London, 1929). K. S. Inglis, “The homecoming: the war memorial movement in Cambridge, England,” Journal of Contemporary Hist. (London), 27 (1992): 583–605. A. J. Kozar, The sport sculpture of R. Tait McKenzie (2nd ed., Champaign, Ill., 1992). D. G. Kyle, “E. Norman Gardiner: historian of ancient sport,” International Journal of the Hist. of Sport (London), 8 (1991): 28–55. Deirdre Martin, “Dr. Robert Tait McKenzie: Canada’s Renaissance man,” Canadian Medical Assoc., Journal (Toronto), 131 (1984): 493–96. Ethel McKenzie, Secret snow (Philadelphia, 1932). Catherine Moriarty, “Narrative and the absent body: mechanisms of meaning in First World War memorials” (phd thesis, Univ. of Sussex, Brighton, Eng., 1995). D. J. Mrozek, Sport and American mentality, 1880–1910 (Knoxville, Tenn., 1983). ODNB. Kineton Parkes, Sculpture of to-day (2v., London, 1921), 1. Penn Medicine, “The history of physical medicine and rehabilitation at Penn Medicine”: www.pennmedicine.org/departments-and-centers/physical-medicine-and-rehabilitation/about-us/the-history-of-physical-medicine-and-rehabilitation-at-penn-medicine (consulted 12 July 2017). J. C. Roberts, “R. Tait McKenzie: Greek sculptor” (unpublished paper, 2006; copy in author’s possession). H. J. Savage et al., American college athletics (New York, 1929). The Scottish Military Research Group – Commemorations Project, “Robert Tait McKenzie”: warmemscot.s4.bizhat.com/warmemscot-post-3181.html (consulted 31 May 2015). Seeking the ideal: the athletic sculptures of R. Tait McKenzie (exhibition catalogue, London Regional Art and Hist. Museums, Ont., 2001). I. M. Thompson, “Robert Tait McKenzie,” Canadian Medical Assoc., Journal (Toronto), 93 (1965): 551–55. J. S. Watterson, College football: history, spectacle, controversy (Baltimore, Md, 2000). Jennifer Wingate, “Over the top: the doughboy in World War I memorials and visual culture,” American Art (Chicago), 19 (2005), no.2: 26–47.

Cite This Article

David Roberts, “McKENZIE, ROBERT TAIT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 20, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mckenzie_robert_tait_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mckenzie_robert_tait_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | David Roberts |

| Title of Article: | McKENZIE, ROBERT TAIT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2021 |

| Access Date: | January 20, 2025 |