Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

WATSON, Sir DAVID, journalist, newspaper owner, and officer; b. 7 Feb. 1869 at Quebec, only son of William Watson, a rigger of sailing ships, and Jane Grant; m. there 11 Sept. 1893 Mary Ann Browning, and they had three daughters; d. there 19 Feb. 1922.

In 1891, having been educated in public schools in Quebec City, David Watson embarked on a career as a journalist with the Quebec Morning Chronicle, which was owned at that time by John Jackman Foote. Ten years later he was appointed general manager of the paper (now the Quebec Chronicle). He became general manager of its publisher, the Chronicle Printing Company, in 1906, and he would hold both positions until 1921. Watson unquestionably made a name for himself at the head of the daily. It was highly profitable, as can be seen from the increase in the number of pages over the years and the extensive advertising in them. Politically, he was an independent conservative, and under him the newspaper, on special occasions, could promote the cause of the Conservative party, which was then led by Robert Laird Borden*. In 1909 Watson was a member of the Canadian delegation to the Imperial Press Conference in London, England.

Watson distinguished himself as an accomplished athlete. For several years he was one of the star players in the old capital’s hockey club. His passion for amateur sports and his strong personality gave him an entry into the Quebec Athlete Association Company, which he would lead over a long period. At the time of his death, renowned businessman Sir William Price would speak of him as a great athlete. Watson also took an early interest in the military, and he would be successful in this sphere as well. He enlisted first as a private in the 8th Royal Rifles, a militia regiment of Quebec City, and then rose through the ranks, obtaining his commission in 1900. Given the rank of lieutenant, he was promoted captain in 1903 and major in 1910. In 1911 he was invited by the federal government to command the company of fusiliers that accompanied the Canadian delegation to the coronation of King George V in England. For this service, he was awarded the Coronation Medal. On 26 Feb. 1912 he took command of his militia regiment with the rank of lieutenant-colonel.

By the beginning of August 1914, Watson was worried about the imminent threat of war in Europe. Wealthy and well known, he enlisted in the first contingent of the Canadian Expeditionary Force at the age of 45. On 22 August he assumed command of the volunteers of the 8th Royal Rifles, which was bound for Valcartier [see Price]. In September he was given command of the 2nd Infantry Battalion of the first contingent of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, a battalion made up of volunteers from eastern Ontario.

After an uneventful crossing in October, the battalion moved into Bustard camp on Salisbury Plain in England with the rest of the Canadian 1st Infantry Brigade. Foul weather made it difficult for Watson’s unit to train. After disembarking in France at Le Havre on 11 Feb. 1915, Watson and his men set out for the deserted town of Armentières, which they reached on 17 February. Mightily impressed by the German artillery fire, Watson made an initial tour of the trenches. He was proud when his battalion took its place there officially on 1 March. As he noted in his diary, his unit was responsible for part of “the great line of defences for the Empire.”

The 2nd Infantry Battalion showed great courage a few weeks later, in the German attack on Saint-Julien (Sint Juliaan), Belgium. During the second battle of Ypres in the spring of 1915, the Germans tried to take this Flemish village and the surrounding area, which jutted into their lines. They attacked on 22 April. For the first time in the war, they resorted to poison gas. At 5:00 p.m. they released more than 160 tons of chlorine, which spread panic among the French troops of the 87th (Territorial) Division and the 45th (Algerian) Division. The soldiers of the 45th were on the front line to the left of the positions held by the 3rd Canadian Infantry Brigade. The retreat of the French troops imperilled the Canadian soldiers, leaving their left flank exposed. During this “great and terrible day,” as Colonel Archer Fortescue Duguid termed it, the soldiers of the 1st Canadian Division, and in particular those of the 3rd Brigade, showed great heroism in stopping the German advance. The 2nd Battalion was stationed near the village of Wieltje. At 9:00 p.m. it received the order to advance towards Saint-Julien, where it was to take part in operations to check the German thrust. The next day (Friday, 23 April), Watson wrote, “My God! What an awful night we have had. Lost about 200 men & 6 officers of no.1 Coy. . . . They are too embedded in my mind to be ever forgotten.” The following day Watson’s men stood their ground in their trenches and inflicted “terrible casualties” on the attacking Germans. At 1:55 p.m. the 2nd Battalion received the order to withdraw. According to Captain Richard Douglas Ponton, “Col. Watson’s gallantry, in remaining in that exposed position until every man had retired, will never be forgotten.” Watson was back at headquarters about 4:00 p.m., “very badly cut up & with less than ½ my battalion.” He noted, however, that his unit “saved all our wounded.” William Waldie Murray, the 2nd Battalion’s official historian, records that the battle of Saint-Julien resulted in the loss of 544 men of all ranks. Only seven of the battalion’s 22 officers came through unscathed. Watson had to reorganize his unit, but he was proud of the conduct of his men, who, in his view, comprised “the best Can. Battn.”

In June 1915 Samuel Hughes, the minister of militia and defence, offered Watson an opportunity to go back to Canada and give the troops the benefit of his experiences in the field. He refused point blank, saying that he “would desire nothing better in all the world than a return to Canada but my duty is here with 2nd Battalion who have been so loyal to me.” Edwin Alfred Hervey Alderson, commander of the 1st Canadian Division, congratulated him on his decision. Watson did accept a promotion, however, and on 30 Aug. 1915 he took command of the 5th Infantry Brigade, with the rank of brigadier-general, as a reward for his battalion’s conduct during the second battle of Ypres. When he returned to the front in the spring of 1916, the machine-gunners of his brigade had to endure the terrible ordeal of the battle of the craters at Saint-Éloi (Sint-Elooi), in Belgium, on 5 and 6 April. This engagement, which lasted from 27 March to 16 April, was so named because of the mines exploded by the British under the German lines on the first day, in a vain attempt to recapture the Saint-Éloi salient. It was the 2nd Canadian Division’s baptism of fire. All the machine-gunners of the 25th and 26th Infantry battalions were killed, while those of the 22nd (except for two) managed to withdraw to the rear, after a hard-fought hand-to-hand battle with the enemy.

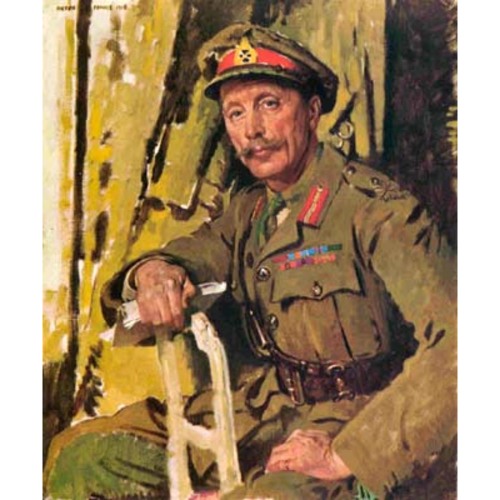

Watson left his brigade on 22 April 1916 and returned to England to take command of the 4th Canadian Division. This was a new one in the Canadian Corps, and a few weeks earlier he had agreed to lead it at the invitation of Hughes. On this occasion, General Alderson (now Sir Edwin Alfred Hervey), mentioned in a letter to Colonel John Wallace Carson (the representative in England of the minister of militia and defence) that Watson “is a good fighting man and gets things done. I think too that he has the moral courage.” Watson would command the unit until the end of the war and, as its leader, he would have difficult duties to perform. The 4th Division underwent its initiation in the fall of 1916, when, after the rest of the Canadian Corps had left for the Vimy sector in France, he was ordered to capture Regina Trench. He succeeded in doing so on 11 Nov. 1916, after several weeks of efforts complicated by bad weather conditions.

It was, then, with a body of seasoned troops that Watson set out again within a few days to rejoin the Canadian Corps, which was defending a wide sector between Lens and Arras. On the first day of the battle of Vimy, 9 April 1917, the 4th Canadian Division was given the job of capturing Hill 145 and a nearby height known as the Pimple. Hill 145 was the highest and most strategically important position on the ridge. It was also the best protected, with two lines of defence. As Gerald William Lingen Nicholson, the historian of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, would later note, “It was thus a valuable prize, though the task of attaining it was formidable.” The 4th Division took three days to reach its objectives. On 12 April Major-General Watson was able to report, “Mission accomplished!”

Under Watson’s command, the division took part next in the battles of Hill 70 (15–25 Aug. 1917) and Passchendaele (26 Oct.–10 Nov. 1917), in Belgium. In 1918 it fought, in France, in the battles of Amiens (8–11 August), Arras (26 August–2 September), and Cambrai (27 September–9 October), the last “the hardest in its career,” said Major Charles Bethune Lindsey, a member of Watson’s staff. The division captured the town of Denain on 19 Oct. 1918 and it took part in the liberation of Valenciennes in November.

On 21 May 1919 Watson presided over a dinner for 200 members of the 4th Division at the Savoy Hotel in London, England. This last meeting before going home was a source of pride to him. On 1 July 1919, with feelings of relief and joy, he saw his home town once again. “So,” his journal noted, “after nearly 5 years of active service, I have returned safe & secure home again. And after what terrible experiences & what fearful hardships & sufferings.” He would scarcely have time to resume his normal activities, however, since he was to die within three years. During that period he carried on his work at the Quebec Chronicle, in which he had purchased a majority of shares shortly after his return. He was also chairman of the Quebec Harbour Commission. According to Colonel William Charles Henry Wood*, the war had undermined his health. He had had heavy responsibilities and had shown great concern for the safety and welfare of his troops. For his bravery and distinguished conduct at the front, Watson was awarded the Croix de Guerre by both France and Belgium and was appointed a commander of the Legion of Honour and the Ordre de Léopold. On 4 June 1917 he had been made a cmg and on 1 Jan. 1918 a kcb. Two years earlier he had been honoured with a cb.

Watson was a Presbyterian and he belonged to a number of prestigious societies, including the Garrison Club of Quebec, the St James Club of Montreal, and the Royal Automobile Club of London, England. A member of the masonic St Andrew’s Lodge No.6 at Quebec, he became deputy grand master for the District of Quebec and Three Rivers. In 1921 he was a member of the founding council of the Canadian Legion of Veterans and he was granted an honorary dcl by Bishop’s College. His business career extended well beyond his work at the Quebec Chronicle, since he sat on a number of boards of directors, including those of the Canadian Bankers’ Association, Mortgage, Discount and Finance Limited, Davie Shipbuilding and Repairing Company Limited, and the Prudential Trust Company Limited. Nonetheless, he remained a thoroughly modest man, according to Wood.

Murray noted that Watson had left an indelible impression as head of the 2nd Battalion. In his words, “‘Davie’ Watson became a legend in the Second. Occasionally a martinet, he was never unfair. Stern he was, and it was not always easy for him to unbend; but he was a competent, able commander, and a just one.” He was the only regimental commander in the militia to command a division in the Canadian Corps.

ANQ-Q, CE301-S67, 16 avril 1869, 11 sept. 1893; Index BMS, dist. judiciaire de Québec, Chalmers Free Church (Chalmers-Wesley United Church, Québec), 21 févr. 1922. LAC, MG 30, E69 (mfm.); RG 9, III, A1, vol. 231, file 6-W-4; RG 150, Acc. 1992–93/166, box 10132-13. Le Devoir, 20 févr. 1922. News (Toronto), 25 Aug. 1915. Quebec Chronicle, 20 Feb. 1922. A. F. Duguid, Official history of the Canadian forces in the Great War, 1914–1919 (only 1v. in 2 pts. [1914–September 1915] was published, Ottawa, 1938). C. B. Lindsey, The story of the Fourth Canadian Division, 1916–1919 (Aldershot, Eng., [1919]). W. W. Murray, The history of the 2nd Canadian Battalion (East. Ontario Regiment), Canadian Expeditionary Force, in the Great War, 1914–1919 ([Ottawa], 1947). Nicholson, CEF. The storied province of Quebec; past and present, ed. W. [C. H.] Wood et al. (5v., Toronto, 1931–32), 3: 22–23.

Cite This Article

Jean-Pierre Gagnon, “WATSON, Sir DAVID,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 21, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/watson_david_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/watson_david_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jean-Pierre Gagnon |

| Title of Article: | WATSON, Sir DAVID |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | January 21, 2025 |