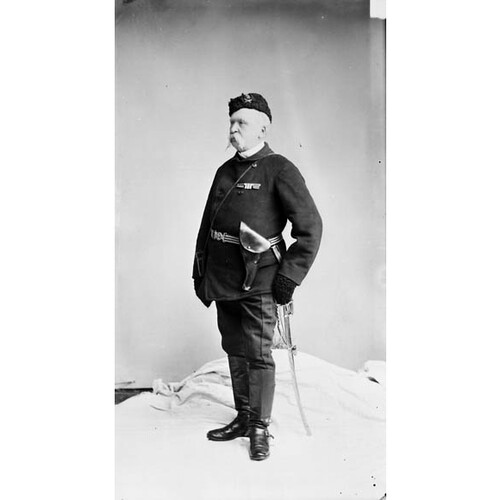

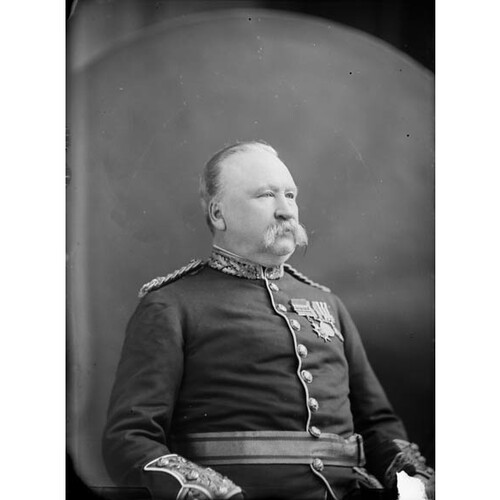

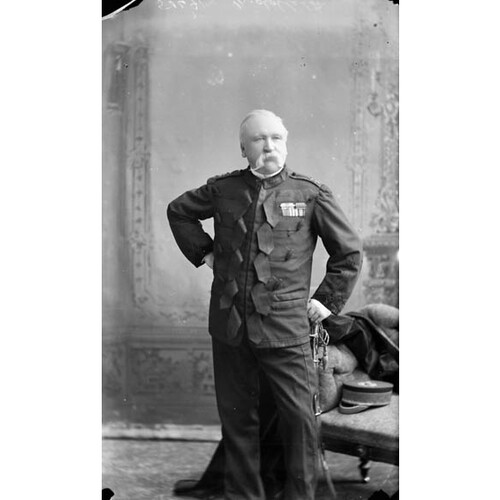

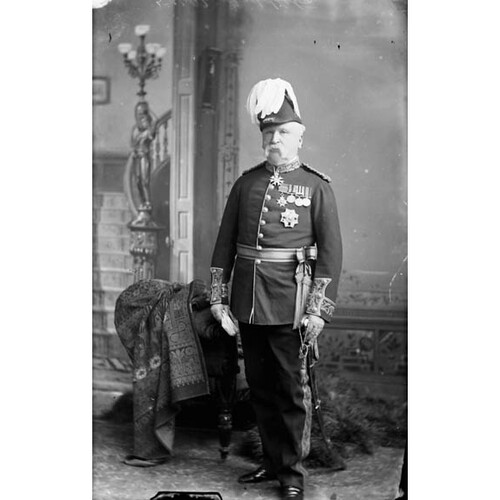

MIDDLETON, Sir FREDERICK DOBSON, army and militia officer; b. 4 Nov. 1825 in Belfast (Northern Ireland), third son of Major-General Charles Middleton and Fanny Wheatley; d. 25 Jan. 1898 in London, England.

Educated in England at Maidstone Grammar School and the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, Frederick Dobson Middleton was granted a commission without purchase in the 58th Foot on 30 Dec. 1842. Two years later the regiment was sent to New South Wales (Australia) and on its way there served as guards on convict ships. Middleton was stationed at the notorious penal colony of Norfolk Island and in 1845, at the outbreak of the rebellion led by Maori chief Hone Henke, he was drafted with his regiment to New Zealand. During a difficult and dangerous campaign, he was mentioned in dispatches for his gallantry at the capture of the stronghold of Maori chief Kawiti and again for his part in repelling a Maori attack on Wanganui.

On 18 Aug. 1848 Middleton secured a lieutenant’s vacancy in the 96th Foot on its transfer to India. An impecunious young officer was likely to find action and advancement there. After completing an examination in surveying, he was gazetted captain on 6 July 1852. In 1855 he commanded a troop of cavalry during the suppression of the Santāl rebellion and earned the thanks of the government of India. When the 96th Foot returned to England in June of that year he exchanged into the 29th Foot, then serving in Burma.

It was a fortunate career move. At the outbreak of the Indian Mutiny in the summer of 1857 he was transferred to Calcutta and served there as an orderly officer. In an age when generals commanded in the thick of battle, staff officers lived dangerously. Two acts of gallantry earned him a recommendation for the newly instituted Victoria Cross, but Lord Clyde, the commander-in-chief in India, ruled that staff officers should not be entitled to the decoration. Instead, on 20 July 1858, he was awarded his brevet majority. During the mutiny he was associated with the controversial innovation of mounting infantry on horseback to enhance their mobility. While hardly a tactical revolution, the idea was sufficiently offensive to traditionalists to mark Middleton, Sir Henry Marshman Havelock-Allan, and others as progressive thinkers in an army of hidebound conservatives.

Middleton returned to England with the 29th Foot in 1859. During 1861–62 he served on Gibraltar and Malta. Well aware that he could never afford to purchase higher rank, he sought promotion through professional training. He completed a 1st class certificate at the School of Musketry at Hythe, Kent, and passed into the Staff College at Camberley in December 1866. The 29th Foot was transferred to Canada in July 1867, but he did not rejoin it until August 1868 because he had not finished his course. After six months in Hamilton, Ont., he went on half pay to accept a series of staff appointments: town major in London, acting assistant quartermaster general in Montreal, and temporary deputy adjutant and quartermaster general from April 1869 until 1870.

Few details survive of Middleton’s first marriage to Mary Emily Hassall of Haverfordwest, Wales. On 17 Feb. 1870, by then a widower aged 44, he married Eugénie Doucet, daughter of Montreal notary Théodore Doucet. He returned to England with his wife that year to become superintending officer of garrison instruction. On 8 Sept. 1874 he was sent to the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, to take up a position as its executive officer and assistant to its governor. Abolition of purchase and the introduction of competitive examinations had altered the role and clientele of the college. Instead of being schoolboys, the cadets were now provisional officers. Middleton had the difficult task of transforming an established although often turbulent institution. He was rewarded with the rank of colonel in July 1875 and the appointment of commandant in 1879, as well as with a cb in 1881. In the summer of 1884 he could expect the end of a respectable but by no means brilliant career and look forward to retirement on the shabby gentility of half pay for himself, his wife, and their two young children.

Canada beckoned as an alternative. In 1875 the government of Alexander Mackenzie had created the position of general officer commanding the militia, to be filled by a British colonel. This position would guarantee professional experience at the head of the force and reassure the British government that Canada was meeting its defence responsibilities. It was mainly for show. With the exception of riots and other minor disturbances, the militia saw no service. City battalions drilled in armouries and provided members with social and athletic activities, but the other half of the 40,000-member force trained only 12 days in alternate years. The annual defence budget, $1,000,000 per year, was largely spent for the benefit of the party in power, particularly after 1880 when Adolphe-Philippe Caron* became minister of militia and defence. The situation was unfortunate for the second general officer commanding, Major-General Richard George Amherst Luard, an energetic, reform-minded, but abrasive officer who tangled with his minister and other politicians.

Middleton was anxious to return to Canada, so he exploited his Canadian contacts. In 1883 he congratulated Caron on a new militia act and on the expansion of the permanent force to 750 men. His wife’s family helped promote his candidacy for the post of general officer commanding, as did Toronto lawyer Christopher Robinson*. “I have never met a man,” Robinson assured the prime minister, “who was less of a ‘soldier and nothing else’ or better able to get on anywhere and with all sorts of people.” In 1884 the War Office removed Luard to another appointment. Both Governor General Lord Lorne [Campbell*] and his successor, Lord Lansdowne [Petty-Fitzmaurice*], had urged the selection of Middleton to replace Luard; Caron, who also favoured Middleton, fended off pressure from politicians to give command to someone else.

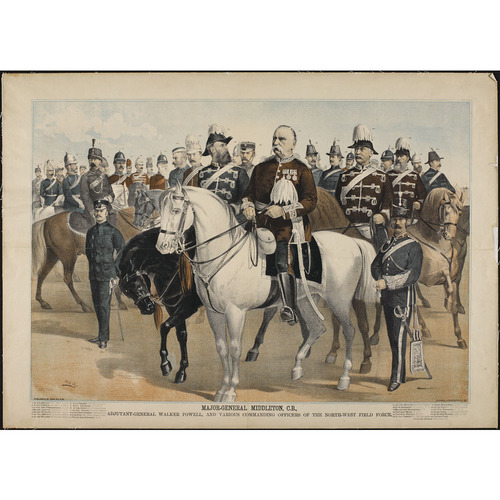

Reporters who met Colonel Middleton at Quebec on 13 July 1884 described him as red-faced, very short, and friendly. He quickly grasped what was expected of him in return for his local rank of major-general and his salary of $4,000. He toured militia camps in eastern Canada, reported that Caron’s new cavalry and infantry schools had “performed wonders,” and claimed of the Royal Military College of Canada at Kingston that “there are very few institutions of a similar character equal to it in Europe and none that are better.” Harsher views of the situation in Canada were reserved for letters to the Duke of Cambridge, commander-in-chief of the British army. A commission on Canada’s defences was established that year by Caron but Middleton gave it little time; its secretary, Colin Campbell, grumbled that Middleton was too busy skating.

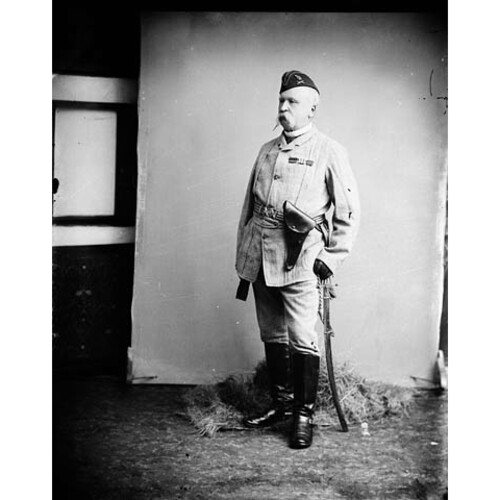

On 23 March 1885, just as word reached Ottawa that Métis leader Louis Riel* had seized hostages near Batoche (Sask.) and formed a provisional government, Middleton was dispatched to Winnipeg at a few hours’ notice. He arrived on 27 March, a day after the battle at Duck Lake (Sask.) between Riel’s lieutenant, Gabriel Dumont*, the victor, and the men led by North-West Mounted Police officer Lief Newry Fitzroy Crozier*. “Matter getting serious,” Middleton wired Caron. “Better send all Regulars and good City Regiments.” Then he set off for Qu’Appelle (Sask.) to improvise the dominion’s first military campaign.

Middleton was 59 and his days of active soldiering should have been over, but under a Blimpish exterior he hid remarkable courage and endurance, considerable common sense, and more practical experience of frontier warfare than most British officers of his seniority. He faced serious difficulties. Even “good City Regiments” were untrained and their officers knew nothing of soldiering. Prairie communities appealed to him to scatter his forces in their defence. Ottawa urged caution. Logistics posed his biggest problem. “These scoundrels have just selected the time when the roads will be almost impassable, the river the same, and all the teams are required almost immediately for seeding.”

Determined to strike at Batoche before the rebellion spread, he left Qu’Appelle on 6 April. Troops from the east joined him along the trail or travelled to Swift Current (Sask.), from where they were to travel down the South Saskatchewan River by steamer. Two Quebec battalions were sent to Calgary where they would face Indians, not French-speaking Métis. News of the Frog Lake (Alta) massacre [see Kapapamahchakwew*] and a strong directive from Caron forced Middleton to divert the column at Swift Current north to Battleford (Sask.). To face the problem of enveloping the Métis at Batoche he ferried half his 800 men to the far side of the river.

So far Riel and Dumont had made his task easier by remaining on the defensive. On 24 April, however, he encountered Dumont and his men at a well-situated position on Fish Creek. His scouts avoided an ambush but the raw militia was unsteady under fire and unable to drive out their Métis and Indian opponents. To reassure his men, Middleton exposed himself recklessly and both his aides-de-camp were wounded. At nightfall, both sides withdrew. The Canadian troops had lost 6 men and counted 49 wounded.

Middleton’s faith in his men and in easy victory faded. The troops, he told Caron, had behaved well “but I must confess . . . that it was very near being otherwise.” To the Duke of Cambridge he wrote of his dismay at the losses of young men “who thought they were going out for a picnic.” The promised steamer Northcote had not arrived. Frustrated, and exhausted from sleepless nights checking on outposts, he found fault with everyone from the eccentric Major-General Thomas Bland Strange*, in charge of the District of Alberta, and Major-General John Wimburn Laurie, supervising supplies at Swift Current, to Lieutenant-Colonel William Dillon Otter*, who had unwisely attacked the camp of Cree chief Poundmaker [Pītikwahanapīwiyin*] at Cut Knife Hill (Sask.). “[Otter] is as inexperienced as his troops,” Middleton complained to Caron.

By 5 May, when the Northcote arrived with supplies and the field hospital, Middleton had recovered his spirits and made fresh plans while his men, reunited on the east side of the river, chafed at the delays. Two days later he led his troops, about 900 strong, away from the river bank. Early on 9 May they advanced on Batoche from the landward side while the Northcote provided a diversion on the river. The steamer arrived an hour early, lost its funnels and mast to a ferry cable the Métis hauled out of the water, and escaped downriver in a furious fusillade. That gave Middleton time to approach, but he paused to bombard the village, giving its defenders opportunity to scramble back to their positions. As at Fish Creek, Middleton’s men were exposed and unsteady. An advance would be costly, a retreat could become a panic. He withdrew to consider his options.

As it happened, the Métis remained passive, the troops sortied with little loss on 10 and 11 May, and Middleton managed to form a plan when he saw the outnumbered Métis racing from the south to the east to defend the approaches to Batoche. Early on 12 May he rode out with mounted troops to feign an attack from the west. When the Métis responded, the sound of his cannon would tell his infantry to attack from the southeast. The gun went unheard. The infantry failed to advance. A furious Middleton roundly abused his officers, among them Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Trefusis Heneage Williams*, and retired to lunch.

That afternoon, when the infantry moved out to reoccupy positions held on 9 May, officers and troops seethed with indignation and frustration. Williams’s men on the left flank cleared their ground and kept moving. Others followed suit. Soon several hundred militia poured down the hill, cheering and shooting. Middleton ran from his tent to organize support. Exhausted and out of ammunition, the Métis could do little. By nightfall they had scattered, the militia were looting Batoche, and Middleton alternately claimed the victory and condemned the folly that had cost 5 lives and 25 wounds that day.

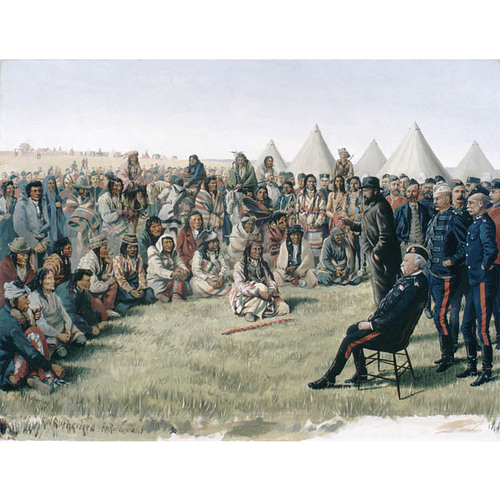

With the fall of Batoche and Riel’s surrender on 15 May, the Métis rebellion was over. Middleton loaned the shivering Riel his greatcoat and sent him south for trial. Then he led his troops to Prince Albert, and west to Battleford to accept Poundmaker’s surrender. For a few weeks militia unsuccessfully pursued Big Bear [Mistahimaskwa*], a task to which the aged general brought little genius. On 22 June, with the last of the Indians’ captives recovered, the troops could go home.

Middleton had shepherded raw troops and inexperienced officers through dangers and difficulties not all of them appreciated, to a much earlier victory than had seemed likely. His official report of the campaign and a series of articles he published in 1893–94 suggest an omniscient wisdom which is the heritage of old generals. Neither he nor most historians recognized how much Riel and Dumont contributed to their own defeat. Still, he had ignored bad advice, overcome obstacles, and prevailed. He earned the thanks of the parliament of Canada, a gift of $20,000 from the Canadian government, a knighthood on 25 Aug. 1885, confirmation of his local rank of major-general, and a British pension of £100 a year for distinguished service.

Few of his subordinates joined in the praise. His troops recognized his pomposity and bad temper as well as his physical courage. Canadian subordinates had been excluded from his narrow circle of British officers. On a host of issues, from his preference for western scouts [see Charles Arkoll Boulton; John French*] over eastern militia cavalry to the events at Batoche, Canadian officers felt antagonized. In Williams, who died of typhoid on his way home, they found their martyred hero. Ill-feeling was aggravated when decorations were limited to the general. Middleton got the blame but, in fact, Caron was responsible. Recognizing that the few decorations Britain would allow to militia officers for so minor an expedition could not possibly satisfy all ambitions, the minister shrewdly chose to distribute none at all.

After testifying at Riel’s trial, Middleton resumed his routine functions. He had received notice from the War Office that his half pay was cut off during his service in Canada, a financial blow which Caron, Sir John A. Macdonald, and Lansdowne joined in protesting but which Ottawa conspicuously failed to remedy by raising his Canadian salary of $4,000. In 1887 the War Office put him on the retired list, with the honorary rank of lieutenant-general, and presumed that the Canadian appointment would be open for a younger man. Caron insisted that Middleton’s performance was entirely satisfactory and that his departure might affect the significant military reforms he himself had in mind. He arranged to extend Middleton’s appointment to 1892. “I fondly hope and trust,” wrote Middleton, “that you will never regret your action in this matter.”

In reality, Middleton no longer had much affection for Canadians or their politicians. “If I would only get an appointment elsewhere,” he wrote to Lord Melgund [Elliot*], Lansdowne’s military secretary, “I would not hesitate to leave this country of vain, drunken, lying & corrupt men but I cannot afford to ‘chuck up.’” Nor had the general as much to do with the new schools for the militia at London and Winnipeg and a new permanent garrison at Esquimalt, B.C., as did the distribution of patronage. Defences made more sense at Vancouver, the terminus of the Canadian Pacific Railway, but like his proposal to turn the NWMP into a mounted infantry, Middleton’s ideas had little influence and he kept them discreetly to himself and his minister. In 1887 a new defence commission was formed but Middleton summoned it to only a single meeting. Canada, he felt, was none the less a good place for a man with few means, a zest for outdoor sports, and a sense of his own importance. As full retirement approached, he looked forward to the presidency of an insurance company.

Suddenly, his career was in ruins. At Battleford a Métis named Charles Bremner who had been arrested in May 1885 found on his release that his furs, stored by the NWMP, had vanished. The trail led to Middleton and his staff, including Samuel Lawrence Bedson. Mounting evidence led Middleton to demand an inquiry. When he appeared before a select committee of the House of Commons on 1 April 1890, he proved an evasive and unsympathetic witness. If he had had the furs seized, someone had subsequently stolen them. “I thought I was the ruling power up there,” he told the members. “I could do pretty much as I liked as long as it was within reason.” The committee did not agree: the seizures were “unwarrantable and illegal”; Middleton’s conduct was “highly improper.”

Middleton was promptly deluged with abuse. He “has degraded his high position, disgraced the uniform of a British officer, and hurt our ideal of the English gentleman,” declared the Toronto Globe. The government disowned him. In July a hurt and bewildered Middleton resigned. Macdonald insisted that Caron edit out any suggestion of sympathy in his letter acknowledging the resignation; it would be “severely remarked upon in Parliament.” In his own defence Middleton published Parting address to the people of Canada, rebutting the Bremner charges and, to meet another painful accusation, listing the names of officers he had proposed for honours in 1885. It was an error. The rage of the officers who had been overlooked was matched by the fury of those who felt entitled to greater distinction. “Poor Middleton,” wrote Caron, “made an awful muck of it.”

British official opinion agreed that Middleton was the victim of a political conspiracy. The general and his family returned to England. He spent his last years writing on topics ranging from sport to mounted infantry for publications as varied as the United Service Magazine and the Boy’s Own Paper. His final account of the 1885 campaign, the articles published in 1893–94, aroused fresh indignation from his Canadian critics. In 1896 he was appointed keeper of the crown jewels, a fitting rebuke to those who had harried him from Canada as a thief. To the end, he remained fit and active, walking daily and skating when he could. He died suddenly in his quarters at the Tower of London.

The author wishes to thank the Royal Arch., Windsor Castle (Windsor, Eng.), for copies of Frederick Dobson Middleton’s reports to his commander-in-chief, the Duke of Cambridge.

Middleton is the author of a number of articles and pamphlets; one of the most important in relation to the Canadian chapter of his career is Parting address to the people of Canada (Toronto, 1890). The account of the rebellion of 1885 that he published as a series of articles in the United Service Magazine (London) in 1893–94 has been republished as Suppression of the rebellion in the North West Territories of Canada, 1885, ed. G. H. Needler (Toronto, 1948).

ANQ-M, CE1-33, 17 févr. 1870. NA, MG 26, A; MG 27, I, D3; II, B1. National Library of Scotland (Edinburgh), Dept. of mss, 12446–587. [C. A.] Boulton, Reminiscences of the North-West rebellions, with a record of the raising of Her Majesty’s 100th Regiment in Canada, and a chapter on Canadian social & political life (Toronto, 1886). Can., House of Commons, Journals, 1890, app.1; Parl., Sessional papers, 1886, no.6a. Globe, 27 June 1890. Times (London), 26 Jan. 1898. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.1. Hart’s army list, 1842–87. Desmond Morton, The last war drum: the North-West campaign of 1885 (Toronto, 1972); Ministers and generals: politics and the Canadian militia, 1868–1904 (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1970).

Cite This Article

Desmond Morton, “MIDDLETON, Sir FREDERICK DOBSON,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 20, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/middleton_frederick_dobson_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/middleton_frederick_dobson_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Desmond Morton |

| Title of Article: | MIDDLETON, Sir FREDERICK DOBSON |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | January 20, 2025 |