Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

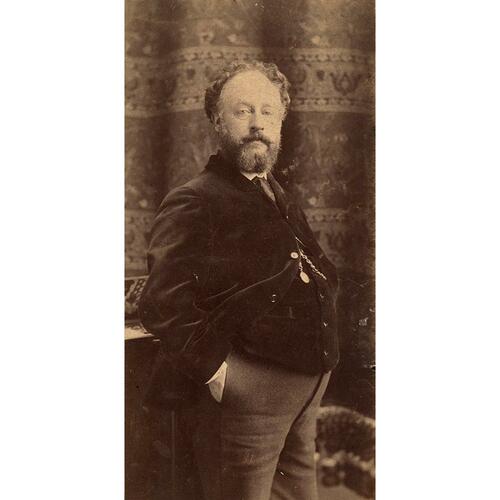

FRASER, JOHN ARTHUR, artist, businessman, and educator; b. 9 Jan. 1838 in London, England, one of five children of John Fraser of Portsoy, Scotland, and Isabella Warren of London; m. 4 April 1858 Anne Maria Sayer in Forest Hill (London), and they had three sons and three daughters; d. 1 Jan. 1898 in New York City.

Little is known of John Arthur Fraser’s years in London, where he lived until the age of 20. A biographical sketch prepared by one of his daughters after his death suggests that he studied drawing in the evenings at the Royal Academy Schools as early as 1852, and a newspaper report of 1864 describes him as “a pupil of the South Kensington School”; his name, however, does not appear in the records of either institution. He is described as “artist” on his marriage certificate, but no work has been identified from this early period in spite of the fact that a biographical note drawn up just before his death claims that in London he earned “a respectable income from portrait painting.” His father, a tailor, was a vocal supporter of the Chartist movement, a political activity his descendants believe led directly to his decision to immigrate to Lower Canada. The whole family left immediately following John Arthur’s marriage, settling in Stanstead in the Eastern Townships, where his grandparents had pioneered in 1831 and where grandmother Fraser had been widowed just two years before. John Arthur is said to have sought work as a decorative painter; his father resumed his occupation of tailor and his passion for liberal politics. Both soon gravitated to Montreal, father writing political commentary under the pseudonym Cousin Sandy while supporting himself as a book agent until his sudden death in 1872, son seeking broader opportunities as a painter.

John Arthur Fraser was first recorded as a resident of Montreal in 1860. According to secondary accounts published at the end of the century and beyond, he was engaged that year by the firm of William Notman not only to tint portrait photographs but to head the newly formed art department. Fraser’s surviving work displays an unusual degree of sensitivity and skill. The earliest pieces are small head-and-shoulders studies worked up with translucent colours that suggest just enough of the presence of paint to give the portraits the appearance of delicate miniatures, the photographic paper resembling the traditional supports of vellum or thin ivory. By 1864 he was art director, Notman’s senior employee. In addition to supervising other staff artists he was producing much larger portraits, not only tinting the by-now usually full-length studio-photographed figure, but placing it within a convincing landscape setting that he painted directly onto the suitably large sheet of photosensitive paper from which all studio props had been carefully masked out in the printing.

At the same time Fraser was displaying landscapes painted in oils with local dealers and at the exhibitions of the Art Association of Montreal. Valued particularly for the strong, clear colour and straightforward compositions of his landscapes of the mountains and lakes of New Hampshire and the Eastern Townships, he became a charter member of the Society of Canadian Artists in 1867. That February his employment with Notman was secured by formal contract, but in May 1868 he was elected to membership in the American Society of Painters in Water Colors, of New York. The election suggests that his ambitions as a painter overshadowed potential opportunities with the Notman firm. None the less, having drawn his final salary from Notman’s Montreal business at the end of October 1868, by 19 November he was settled in Toronto where, in partnership with his former employer, he had opened the photographic firm of Notman and Fraser.

We know little of Fraser’s first years in Toronto, which doubtless were turned largely to assuring the success of his new business. After 1868 he virtually stopped exhibiting in Montreal, and he failed to exercise his membership in the American Society of Painters in Water Colors, which lapsed. Then, on 25 June 1872 Fraser convened a meeting with six other local artists at his home, and on 2 July he was elected vice-president of the new Ontario Society of Artists. (The honorific presidency was to be filled by a patron, the post initially going to William Holmes Howland.) The first exhibition opened in the new, larger, custom-designed facilities of Notman and Fraser on 14 April 1873. Three artists were singled out for particular attention in the press: Lucius Richard O’Brien, Frederick Arthur Verner, and Fraser, who showed a water-colour and five oils, all but one views in the Eastern Townships. Two of the oils, both in the collection of the National Gallery of Canada, can be identified. September afternoon, Eastern Townships and the one Ontario scene, A shot in the dawn, Lake Scugog, a location northeast of Toronto, are both dated 1873. The latter shows two hunters against a spectacular autumn sunrise, the former depicts two men resting by a small boat on the shores of Lac Memphrémagog while sheep graze in the immediate foreground. Works of vivid colour and striking clarity, these paintings, in their matter-of-fact handling of anecdote, close attention to detail, crystalline atmosphere, complex and unconventional spatial composition, and use of the newly available coal-tar colours, reflect the landscape style of the Pre-Raphaelite painters, at that time just passing the peak of their popularity in Britain. September afternoon in particular also reveals the influence of photographic imagery with its use of a series of clearly defined planes to establish recession, its emphasis upon foreground texture, and a general tendency to sharp tonal contrast and flatness in the darks. The startling naturalism of Fraser’s canvases was much praised at the time, as was his skilful handling of paint.

Shortly after the exhibition Fraser was re-elected vice-president of the OSA. Before the year was out, however, he was being criticized for his handling of the discovery that the treasurer, a merchant whose business was failing, had embezzled the society into debt. At the next elections, in June 1874, he was replaced by O’Brien, who appears to have led the criticism. Fraser resigned his membership in December and withdrew entirely from painting. The Notman and Fraser firm flourished, and during the spring and summer of 1876 he took on an added responsibility as art superintendent of the Centennial Photographic Company, established by Notman to provide services for the Philadelphia Centennial International Exhibition.

The extensive art display there must have stimulated Fraser, and in February 1877 he allowed himself to be re-nominated to membership in the OSA. That summer he travelled to the Baie des Chaleurs region of New Brunswick on the new Intercolonial Railway to sketch, and in May 1878 he contributed the most paintings he ever submitted to the society’s annual exhibition, to much acclaim. There are both watercolours and oils of these eastern subjects, works that are generally more ambitious in scale and finish and more distinctive in colour and composition than those he had produced during his initial push to establish himself as a landscape painter a decade earlier. He was elected the painter representative to the council of the Ontario School of Art, in Toronto, and that same year, 1878, he finally began to exhibit with the American Water Color Society (as the American Society of Painters in Water Colors had become). He assumed the general supervision of evening classes at the school of art on 11 September, the first of a number of positions he would fill there over the next few years. Although he earlier had imparted his knowledge of painting to younger men under his supervision at Notman’s in Montreal and at Notman and Fraser in Toronto – Henry Sandham* in the mid sixties and Robert Ford Gagen, Homer Ransford Watson*, and Horatio Walker* in the early seventies benefited from his guidance – it was only during this period that he undertook formal teaching. George Agnew Reid* and Ernest Evan Thompson Seton [Thompson*], who would be prominent a decade later, were among those who studied with him then.

Fraser’s impressively energetic return to Toronto’s artistic circles assured both his selection as a charter member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts in 1880 [see John Douglas Sutherland Campbell*] and his involvement in preparing drawings for the massive publishing project launched that year, Picturesque Canada [see George Monro Grant*], for which he went back to the east coast in the summer to sketch. But his success was not to last. His sketches were rejected by the publishers, and sensing, with reason, that they were reneging on their promise to use Canadian talent throughout, he so accused them publicly in October. (One of his Eastern Townships sketches was eventually included.) Lucius O’Brien, who was art editor on the project and president of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, he also attacked, and acrimonious feelings between them surged up again, never to subside fully.

Stubbornly proud, Fraser must have felt virtually excluded from remunerative art activity in Toronto, but a new option developed in the summer of 1883 when he found an opportunity to travel once more as an illustration artist. Working for a Chicago publisher, he went first for about two weeks into northern Wisconsin to prepare sketches that were later used to illustrate an article he wrote about the journey, and then until about the middle of September he covered the just-completed section of the Canadian Pacific Railway [see George Stephen*] between Calgary and Port Arthur (Thunder Bay), Ont., as a guest of the company. Some time during 1883 the Notman and Fraser partnership was dissolved and in June 1884 the photographic firm of Fraser and Sons first advertised for business in Toronto. Fraser left the sons in charge and early the following year joined his wife and daughters in Boston, where his brother William Lewis Fraser and Henry Sandham, now his brother-in-law – both former Notman employees who had earlier moved from Montreal – steered illustration work to him. That year he joined the Boston Art Club and became a charter member of the Boston Water Color Society. By March 1886 Fraser and Sons, and its entire stock of negatives, was sold. Fraser was then working steadily as an illustrator for Century Illustrated Magazine and other New York monthlies.

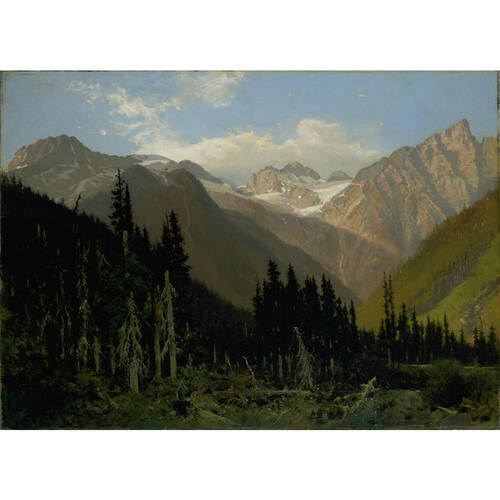

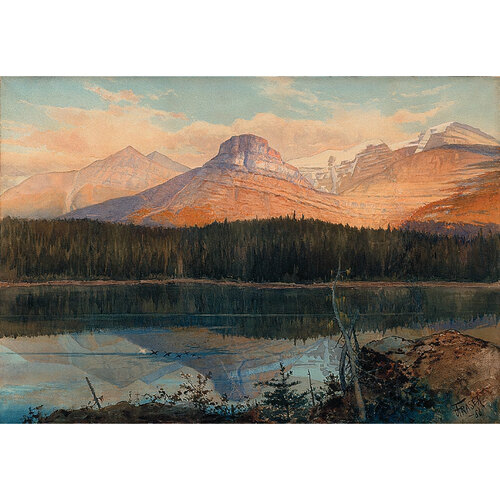

Fraser’s Canadian career had not ended, however. His earlier connection with the CPR led to a commission from William Cornelius Van Horne* early in 1886 to paint in Boston three large water-colours from the railway’s collection of photographs of the Rocky Mountains for inclusion among the nine Fraser paintings in the Canadian art display at the Colonial and Indian Exhibition, in London, as a way of promoting the railway’s new line through the mountains. The London critics judged the younger Canadian artists, French-trained figure painters such as William Brymner*, Paul Peel, Robert Harris*, and Percy Franklin Woodcock*, to be the most interesting, hardly noticing the work of Fraser and the other landscape painters of his generation. On the other hand, a report on the Canadian display commissioned by the governor general, Lord Lansdowne [Petty-Fitzmaurice*], and written by the librarian of the Royal Academy of Arts, singled out Fraser’s Rocky Mountain water-colours for the highest praise, extolling the distinctively Canadian atmosphere evident in their striking naturalism.

In the summer Fraser finally saw the Rocky Mountains when he was sent out along the entire length of the CPR line to sketch, as were other Canadian artists that year and subsequently. He left Montreal on 8 June 1886, travelling to Vancouver Island before sketching, and then working his way back east through the mountains, his view much hindered by the smoke of forest fires. He returned to Toronto finally on 19 October bearing numerous water-colours, both sketches and larger, more finished pieces. These mountain pictures have always been considered Fraser’s most characteristic work. Like the paintings based on photographs he had done earlier in the year, they are highly naturalistic and relate more to the conventions of the camera image than to traditional landscape painting. An exhibition the second week of November of the Rocky Mountain paintings – possibly including some oils completed after his return – was warmly received and repeated in Montreal, but by the end of November he and the family were settled again in Boston.

John Fraser maintained connections with Canada, particularly with the officers of the CPR, but he never worked there again. In March 1887 he held an exhibition of his CPR paintings at the Canadian Club, in New York, and in May he showed them with a dealer in London; both exhibitions were facilitated by the railway company. He returned to Britain in the spring of 1888, visiting Scotland and Kent. Then, lodging in London, he worked up exhibition pieces until his health gave out in the summer of 1889. One of his Scottish water-colours was accepted in the Royal Academy of Arts exhibition that year. Back in the United States, Fraser and his wife settled in New York City where, in 1890, he began to exhibit – with the Society of American Artists, the New York Water Color Club, and the National Academy of Design – primarily his new British water-colours but the occasional American subject as well. He continued to show in Canada and Boston, and in 1891 had water-colours accepted in the Paris Salon. But his life was increasingly centred on the tight circle of water-colourists and illustrators in New York who frequented the Salmagundi Sketch Club and showed with the local societies. He was elected to the board of control of the New York Water Color Club for 1893 and 1894, and to that of the American Water Color Society for 1894 and 1895. He was by then no longer exhibiting in Canada, although Toronto had one last chance to see his work when he staged an auction there in October 1897, less than three months before his death.

Fraser was a restless, ambitious, and, some have suggested, vain man, perfectly suited to the tremendous growth and geographical expansion that took place during his years in Canada. At the centre of most of the attempts of his day to organize Canadian artists along professional lines, he soon found himself alienated from these organizations, his painting production rising and falling in response to his status. Painting rarely dominated his interests and often was abandoned entirely for other business pursuits, but it is as a painter that he will be remembered. Fraser was, on the other hand, wholly engaged by both the growth of photography and the expansive vision of nationhood fostered by the rise of the railways, and it is the conjunction of these concerns in his painting that gives it such memorable force.

John Arthur Fraser is the author of “A scamper in the Nor’-west,” Outing and the Wheelman (Boston), 5 (1884): 83–90, and “An artist’s experiences in the Canadian Rockies,” Canadian leaves (New York, 1887), 233–46. A number of his tinted portrait photographs dated from 1861 to about 1868 are held in the McCord Museum, Notman Photographic Arch. Only a handful of his paintings survive. The largest public collection is that of the National Gallery of Canada (Ottawa); the Beaverbrook Art Gallery (Fredericton), the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, the Art Gallery of Hamilton (Hamilton, Ont.), the Art Gallery of Ontario, the CTA, and the Hist. Picture Coll. of the MTRL in Toronto, the London Regional Art Gallery (London, Ont.), and the Glenbow Museum (Calgary) hold smaller numbers of his works. Two portrait photographs of Fraser done by the Notman studio are reproduced in Reid, “Our own country Canada”, which contains the most detailed study of the artist yet published.

ANQ-M, CN1-26, 21 févr. 1867 (copy at McCord Museum, Notman Photographic Arch.). AO, MU 2254. Arch. of American Art, Smithsonian Institution (Washington), American Water Color Soc., minutes, 5 May 1868. Art Gallery of Ontario (Toronto), Curatorial files, L. R. O’Brien, scrapbook (photocopy); Library, R. F. Gagen, “Ontario art chronicle” (typescript, c. 1919). Canadian Pacific Arch. (Montreal), Van Horne corr., 1883–87. Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Library, Scrapbooks, I (1864–87): 6; III (1886–92): 18. Greater London Record Office, St George in the East (London), Reg. of baptisms, marriages, and burials, 21 July 1835, 3 Feb. 1838. McCord Museum, Ontario Soc. of Artists, letter-book, 1886; Notman Photographic Arch., Montreal studio records, Notman wages book (1863–1917). Private arch., [Joan Sullivan] Mrs Frank Muller (Bakersfield, Calif.), Diary of Nanette Fraser, 1886–88. American Art Annual (New York), 1 (1898): 30. American Water Color Soc., [Exhibition catalogue] (New York), 1878, 1883, 1885–86, 1888, 1891–96. Art Assoc. of Montreal, [Exhibition catalogue], 1864, 1872, 1883, 1886, 1891, 1894. Boston Art Club, [Exhibition catalogue], 1884–86, 1890, 1895. New York Water Color Club, [Exhibition catalogue], 1890–93. Ontario Soc. of Artists, [Exhibition catalogue] (Toronto), 1873, 1877–82, 1886, 1890. Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, [Exhibition catalogue] (Ottawa), 1880–81, 1886, 1890–91, 1893–94. Soc. of Canadian Artists, [Exhibition catalogue] (Montreal), 1868. Canadian Illustrated News (Montreal), 15 June 1872. Globe, 19 Nov. 1868, 29 May 1878, 16 Sept. 1880, 10 Nov. 1886. New York Times, 3 Jan. 1898. Times (London), 2 June 1887. Toronto Daily Mail, 11 Nov. 1886. Week, 5 June 1884, 18 March 1886, 23 Aug. 1889. World (New York), 14 March 1887. Canada, an encyclopædia (Hopkins), 4: 401–2. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). Harper, Early painters and engravers. Montreal directory, 1859–60. Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, formerly Art Association of Montreal; spring exhibitions, 1880–1970, comp. E. de R. McMann (Toronto, 1988). Maria Naylor, The National Academy of Design exhibition record, 1861–1900 (2v. , New York, 1973). Royal Canadian Academy of Arts; exhibitions and members, 1880–1979, comp. E. de R. McMann (Toronto, 1981). Catalogue of paintings . . . by the late John A. Fraser, with a short biographical sketch . . . ([New York)], 1901). J. R. Harper, Painting in Canada, a history ([Toronto], 1966). K. L. Kollar, “John Arthur Fraser (1838–1898)” (ma thesis, Concordia Univ., Montreal, 1981); John Arthur Fraser (1838–1898), watercolours (Montreal, 1984). D. [R.] Reid, A concise history of Canadian painting (2nd ed., Toronto, 1988). Rebecca Sisler, Passionate spirits; a history of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, 1880–1980 (Toronto, 1980).

Cite This Article

Dennis Reid, “FRASER, JOHN ARTHUR,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 21, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fraser_john_arthur_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fraser_john_arthur_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Dennis Reid |

| Title of Article: | FRASER, JOHN ARTHUR |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | January 21, 2025 |