Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

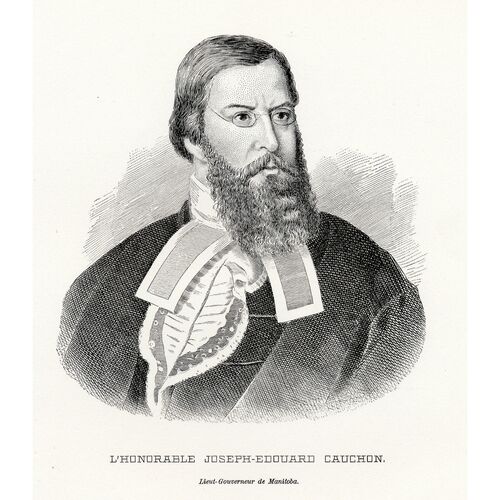

CAUCHON, JOSEPH-ÉDOUARD, journalist, businessman, and politician; b. 31 Dec. 1816 at Quebec City, son of Joseph-Ange Cauchon, fils, and Marguerite Valée; d. 23 Feb. 1885 in the Qu’Appelle valley (Sask.).

Joseph-Édouard Cauchon was a descendant of one of the oldest families in the colony. His ancestor Jehan Cochon, originally from Dieppe, in Normandy, France, is thought to have arrived in Canada with his family, including a son named Jean, about 1636. Having come as a settler rather than an indentured employee, Jehan obtained a land grant in the Beaupré seigneury which the Compagnie des Cent-Associés was then making special efforts to settle. His son secured a similar grant in the same period, and from 1652 to 1667 held the office of seigneurial attorney. He was thus a member of the “public service bourgeoisie” which was concentrated in the region around Quebec City and engaged in both agriculture and administration. In 1680, for unknown reasons, the name Cochon was written Cauchon, and the more elegant form remained in use. The family established itself on the Beaupré shore and apparently did not move to the city until the sixth generation. It is known that Joseph-Ange was a dairyman at Quebec when he married Marguerite Valée on 14 April 1814. Their son Joseph-Édouard was born two years later in Saint-Roch parish in Quebec City.

Joseph-Édouard Cauchon received his classical education at the Petit Séminaire de Québec from 1830 until 1839 when he began to study law in the office of James George Baird. In 1841 he published at Quebec a handbook, Notions élémentaires de physique, avec planches à l’usage des maisons d’éducation, which was of limited scientific and pedagogical value but which drew attention to its youthful author. From 1841 to 1842 he also worked as a journalist for Le Canadien, a paper then printed by Jean-Baptiste Fréchette; Cauchon replaced Étienne Parent*, who as representative for Saguenay County had to go to Kingston, Canada West, for the first two sessions of the Legislative Assembly of united Canada. Cauchon’s experience with the paper profoundly influenced his future. Although he was called to the bar in 1843, he never practised law, and was to be a journalist and politician.

With his brother-in-law Augustin Côté*, Cauchon launched Le Journal de Québec on 1 Dec. 1842. This paper replaced the French edition of the Quebec Gazette which after a number of interruptions had ceased publication on 29 October as a result of insuperable financial difficulties. Cauchon was proprietor from 1842 to 1862 and editor from 1842 to 1875, except for the years 1855 to 1857 and in 1861 when he was a member of the government. Originally a biweekly, in folio of two pages, Le Journal de Québec resembled other 19th-century newspapers, particularly in the columns it carried. It mainly discussed politics and religion, and tended to support the Reform position. It took its provincial and international news from Canadian and foreign papers and gave extensive coverage to municipal, economic, and literary activities of the Quebec region. According to a circular of 5 Nov. 1842 Le Journal de Québec aspired to be a “palladium of liberty.” It declared itself independent of men and parties, and would extend support to one or the other “solely for the sake of principles.” Both nationalist and unionist, it would convey French Canadian views first and foremost but was ready to offer “a willing hand to all . . . who desire the advancement and prosperity of [our] common native land.” This ideal would be eroded by the impetuous personality, ambition, and personal interests of Cauchon, who for almost all his political career was its guiding spirit.

It is difficult to gauge Cauchon’s work as a journalist since Le Journal de Québec has not yet been systematically studied. Furthermore, contemporary testimony concerning Cauchon was always tainted by party passions. In the opinion of Liberal Laurent-Olivier David*, Cauchon was “ambitious, violent, enamoured of money, honours, and luxury, lacking in scruple, enterprising, full of shifts and expedients.” On the other hand Alfred Duclos* De Celles, a friend of the Conservatives, admired Cauchon who had “read everything, retained everything – history, constitutional law, political economy.” Again, for La Patrie of Montreal, Cauchon was an unpredictable journalist able to disconcert the most unruffled opponent – the only one “who ever succeeded in driving the wise and worthy Étienne Parent into a rage.” From all these testimonies, although in many ways contradictory, Cauchon emerges as a journalist who made an impact with his keen intelligence, violent and energetic nature, and scathing pen.

Cauchon and his influential Journal de Québec entered into all the public discussions of the day, which in the final analysis were political. As examples one might cite articles written to counter his opponents: George Brown* and the Globe (Toronto) on educational and religious questions and on the principle of “rep by pop”; Télesphore Fournier and Marc-Aurèle Plamondon of Le National (Quebec) on the radical ideology of the Rouges (the name, taken by Cauchon from the French radicals, was to become the accepted one); Louis-Antoine Dessaulles* and Le Pays (Montreal) on the democratic nature of the government; and Joseph-Charles Taché* and the Courrier du Canada (Quebec) on the principle of confederation and on school reform.

The most famous of these debates was on confederation, a subject which inspired Cauchon to write two pamphlets. In 1858 he came out against an initial plan in a series of articles which he published at Quebec as a brochure entitled Étude sur l’union projetée des provinces. The scheme was still quite vague, and the author examined it on the basis of 27 hypotheses which summed up the problems of the union. In July 1864, when the coalition of George Brown and Sir Étienne-Paschal Taché* had just been formed, Cauchon returned to the subject in a series of articles published at Quebec between 12 Dec. 1864 and 28 Jan. 1865. This series constitutes the political essay entitled The union of the provinces of British North America, published in both French and English; its value as a document has been confirmed by historians studying the confederation period. In it the author first gradually cleared away his arguments of 1858 and, having pointed out the important steps in the constitutional history of Canada since 1840, he established that the union of the provinces, as one or on a federal basis, had become a political necessity. He then declared himself in favour of a centralized federal system, resembling a legislative union rather than the American constitution. Finally he defended each of the 72 Quebec Resolutions, which the parliament of Canada would soon be invited to ratify, and concluded that the proposed confederation would guarantee the protection of the privileges, long-standing rights, and special institutions of Canada East. This work, which supported those favouring confederation, revealed Cauchon’s political affiliation. Indeed in 1864, after 20 years of political life, he had become one of the most powerful Conservatives in Canada East.

Cauchon had entered politics in 1844. That year he was elected for Montmorency County, defeating Frédéric-Auguste Quesnel*. He represented this constituency throughout his political career, being elected “by acclamation” in 1848 and 1861 and facing opponents in 1851, 1854, 1857, and 1863. As was customary, some of these elections were marked by corruption and violence.

In the parliament of united Canada, Cauchon immediately associated his name with the politicians who would be called upon to play a decisive role in the country’s history. He supported the Reform policy of Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine* and Robert Baldwin*; with Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau, he fought to get Augustin-Norbert Morin* elected speaker of the house because he was bilingual; he waged war on Louis-Joseph Papineau*, whom he categorized as one of those “men who are powerful destructive [forces], but who have never built anything on the ruins they have made.” In parliament Cauchon therefore supported the great political compromise that followed the failure of the 1837–38 rebellion and led to ministerial responsibility. Moreover, in a debate in 1849 on the repeal of union Cauchon defended union because it ensured equal representation in parliament and thus guaranteed the institutions and laws of each section of the province. But Cauchon expressed his opposition in 1851, disapproving of the alliance of the government, then under Francis Hincks and Augustin-Norbert Morin, with Brown’s Clear Grits, whose “democratic, socialist and anticatholic” principles he condemned. He even refused the offer Hincks made him of the post of assistant provincial secretary without a seat in the cabinet. Cauchon’s distrust of the government, an attitude he expressed both in parliament and in his Journal de Québec, helped to weaken the government and the Reform party.

Cauchon, with his “brother in arms” Louis-Victor Sicotte, was responsible for the defeat of the Hincks-Morin government in 1854 which signalled the formation of the Liberal-Conservative coalition. He enthusiastically welcomed the events of 1854, even though they blighted his well-known hopes of becoming prime minister. Indeed those hopes were bound up with the political crisis of 1854, which the Liberal-Conservative coalition resolved. Under the government of Sir Allan Napier MacNab* and Morin in 1854 Cauchon firmly supported the bills abolishing the seigneurial régime and secularizing the clergy reserves.

When the government was reconstituted under MacNab and Étienne-Paschal Taché in 1855, Cauchon made his presence felt by introducing a bill to make the Legislative Council elective. Appointed commissioner of crown lands for Canada East that year, he retained this post under the new government of Taché and John A. Macdonald* but resigned in April 1857 over the issue of the North Shore Railway. The story of this railway really began in 1852 when the era of Canadian railways had just dawned. It was incorporated in 1853, at the time the government decided to subsidize the building of the Grand Trunk from Montreal to Lévis, on the south shore. The promoters of a railway on the north shore between Montreal and Quebec asked for similar assistance. The government refused, asserting that this railway was of local rather than provincial interest. Convinced that only a north shore railway could improve the economic situation of Quebec City, Cauchon devoted his energies to the project from 1855; time and again, as his correspondence shows, he approached Quebec City, the north shore municipalities, and London financiers for the necessary funds. In 1857 the plans and estimates were ready but there was still no capital. Cauchon then gave the government an ultimatum: he asked for a grant of land for the railway and threatened to resign as commissioner if it was not made. The government accepted Cauchon’s resignation, but a few months later granted 1,500,000 acres of uncultivated land to the venture. It should be pointed out that land transferred by the government to the railways served in that period as a guarantee for loans which the companies would have had to negotiate in the financial markets. For its part Quebec City voted a subsidy of $50,000. However, the project had to be suspended when approaches to London financiers proved unsuccessful. It was obvious that the obstacle was the Grand Trunk Railway [see James Bell Forsyth*], a fact unlikely to give Cauchon warm feelings towards such colleagues such as Étienne-Paschal Taché, who was personally involved in the Grand Trunk venture. Consequently Cauchon showed himself particularly jealous of his political autonomy after 1857, and when voting in the house fluctuated between the right and the left.

He even became an opponent of the government of John A. Macdonald and George-Étienne Cartier* in 1858, openly supporting the principle of double majority [see Thomas-Jean-Jacques Loranger]. During a parliamentary debate on this question Cauchon asserted that the federal principle, which was the basis of the union of the two Canadas and had been ratified in 1848 by the government, “can be real only to the extent that the executive councillors from one section of the province enjoy the express confidence of the majority of its representatives.” On two major matters, the seat of government and the bill on customs duties, introduced by Alexander Tilloch Galt*, Cauchon also voted against the Cartier-Macdonald government, and in his Journal de Québec he opposed the confederation scheme which had been included in the government’s platform at Galt’s insistence.

In short Cauchon displayed certain liberal leanings. Officially, however, he was still a supporter of the Liberal-Conservative party. During the 1860s, when party lines became strongly drawn, he always backed the Conservative government. He was even minister of public works from 1861 to 1862, and in 1864, although he had been opposed to any constitutional change, as noted earlier, he became one of the most ardent advocates of confederation. During the subsequent debates he devoted a great deal of time in particular to explaining the clauses pertaining to the Senate, judicial organization, marriage, and divorce. He also made himself the defender of a provincial legislative council but vigorously objected to the clause giving special protection to certain counties in Canada East which were predominantly English-speaking; he considered it an affront to French Canadians, who had always respected the rights of Protestant minorities. The support he had given to the federative plan, the authority he enjoyed at Quebec, and the respect he commanded in political circles made him the natural choice in 1867 as prime minister of the new province of Quebec.

Immediately after confederation Cauchon was called upon to form the government. He set to work, but encountered a major obstacle which led to his failure. In order to secure in the government adequate representation of the various social groups, Cauchon offered the portfolio of provincial treasurer to Christopher Dunkin, a converted opponent of confederation. At Galt’s suggestion, Dunkin accepted on condition that the education bill of Hector-Louis Langevin* be revived in the Quebec legislature. This bill had given the last government of united Canada some trying moments in 1866. In effect the 1866 Langevin bill was designed to give the Protestant minority in Canada East the independence it had long desired in the field of education, and was financially favourable to the Roman Catholic majority. That same year Robert Bell*, a young Irishman in Canada West with a lofty sense of strategy, introduced an education bill which was favourable to the Catholic minority of Canada West but which had no chance of being passed. In his Journal de Québec Cauchon supported the claims of the Catholic minority in Canada West and censured the ministers who refused to introduce Bell’s bill as a corollary to Langevin’s; although he favoured a recognition of the rights of the Protestant minority, he objected to the creation of a Protestant superintendent of education in Canada East. Faced with this dilemma Langevin had withdrawn his own bill to avoid exposing the government of John A. Macdonald and Narcisse-Fortunat Belleau* to defeat. In 1867, Cauchon could not reintroduce a bill which took no cognizance of his earlier objections. Consequently Dunkin was ruled out. Yielding to the obvious fact that under Galt’s influence, any Protestant representative would act as Dunkin had, Cauchon abandoned the idea of forming a government and becoming prime minister of Quebec. He did, however, continue as the member for Montmorency in the Legislative Assembly of the province from 1867 to 1874.

But a man of Cauchon’s calibre and ambition could not be content with a mere representative’s seat in the Quebec parliament. In October 1867 he accordingly issued an ultimatum to his friends in Ottawa: he wanted “the lucrative post of senator and speaker of the senate.” This explicit demand precipitated the resignation of Belleau from his seat for the division of Stadacona within six days; Cauchon was appointed to succeed him and then to the speakership of the Senate, a post he held from November 1867 to May 1869. This move was looked upon with disfavour in political circles, whether they were hostile or friendly to the government. The government’s “underhand dealing” was denounced in terms sometimes verging on insult. Thus Senator George Crawford* upbraided the government for sending to the Senate “the only ‘Cochon’ in the House”: “he is a ‘cochon’ [pig] in his appearance, in his bearing, in his table manners and in parliament.” The appointment, made despite wide opposition, is fairly indicative of the pressure Cauchon brought to bear and indeed of his ascendancy within the Conservative party, not only in the Quebec region but also at the provincial and federal levels.

His power was exerted in another sphere. He was mayor of Quebec City from 1865 to 1867 but it is difficult to assess what he accomplished since he never published a report, for which he was rightly blamed by his political enemies. The major event during his term of office was the fire on 14 Oct. 1866 which totally destroyed the suburbs of Saint-Roch and Saint-Sauveur; nearly 3,000 houses were lost and 15,000 persons were left homeless. Cauchon organized a permanent fire brigade with a telegraphic alarm system at a cost of $38,120. To this end he raised the budget of the municipal fire committee from $4,000 to $9,000. In addition he is said to have collected more than $500,000 for the disaster victims. But he was overwhelmingly defeated in the municipal elections of December 1867 by John Lemesurier who had the support of the working class.

Ousted from both the provincial government and the Quebec City Council, Cauchon had therefore to direct most of his energies to the Senate. But the upper house was much too calm and peaceful an arena for him. Consequently he resigned on 30 June 1872, to return on 7 Aug. 1872 to the House of Commons where he had briefly held a seat in 1867. This time he came as an independent member for the riding of Quebec Centre. The opposing candidate had been James Gibb Ross, who represented the Protestant English minority in the city. The campaign, “the fiercest that has ever been seen at Quebec,” had developed into a struggle between nationalities, and had been marked by a pistol fight in the Protestant cemetery on Rue Saint-Jean. This fight had left numerous casualties in both camps and one of Ross’s supporters had been killed. Because he had a great deal of influence at Quebec as the president of the North Shore Railway Company, a director of a number of banks, and the owner of the Asile de Beauport (Centre hospitalier Robert-Giffard) and Le Journal de Québec, Cauchon had emerged the electoral victor. He was evidently economically well situated; he was in addition one of the directors of the Interoceanic Railway Company of Canada (1872–73). At Quebec he was said to be rich. In fact he lived like a pasha. The stone house at 63 Rue d’Auteuil which he had bought in 1855 was like a palace-cum-museum. Its architecture was sumptuous and there were rooms set aside for the numerous works of art that Cauchon had brought back from his frequent trips to Europe.

Cauchon, who with his brother-in-law formed the firm of A. Côté et Compagnie, had a good credit rating with R. G. Dun and Company of New York. According to the brief comments in the handwritten register for Quebec City for the years 1855–63, it is clear that the two men possessed next to nothing in 1855, although they had been in business for 15 years. At that time their credit rating was based only on the official patronage Le Journal de Québec enjoyed. But in the years after 1857, when the patronage had ceased temporarily, they were still given the same rating by R. G. Dun because they were recognized as “reliable businessmen who have sufficient capital at their disposal.” In 1861 the register mentions that the two men also had in their favour the support of the clergy and their influence with the government, Cauchon being at that time minister of public works and well looked after by governmental patronage. But it is certain that Cauchon acquired wealth by other means and that land speculation was his most lucrative source, as is evident in the numerous notarial acts which have been located.

In 1873 Cauchon’s ambition and hopes were reawakened by a number of events. Belleau’s term of office as lieutenant governor was expiring, and Cauchon coveted the post. But he had far too many enemies and his prestige was declining, so there could be no question of conferring this office on him. Indeed the Beauport asylum affair had seriously undermined his standing in the province. Despite skilful subterfuge on his part, it had been proved that Cauchon had been the real owner of the asylum since 1866, the physicians Jean-Étienne Landry and François-Elzéar Roy serving him as figureheads, and that Cauchon was reaping all the profits from the business. The asylum had been subsidized before 1867 by the government of united Canada, and after that date by the government of Quebec, which created a conflict of interest for Cauchon who was then a member of the Legislative Assembly. But it was not until 1871 that the opposition in the Quebec assembly tried to develop this into a scandal which would overthrow the government. Cauchon, however, continued to outwit his enemies. His electoral mandate was challenged during the session of December 1871 but the investigating committee was unable to reach a conclusion in the absence of one important witness. Meanwhile Cauchon sold all his interests to Dr Roy. The committee resumed its inquiry in the 1872 session and reported to the assembly. On 10 Dec. 1872, at the moment when the representatives, were to decide the validity of Cauchon’s election, he tendered his resignation to the speaker. He again ran for election in Montmorency County, resumed his seat in the assembly at the end of the session, and kept it until 1874; he then resigned from his post for good as a result of the abolition of the double mandate permitting members of the House of Commons to sit also in a provincial legislature.

When Cartier died in May 1873 Cauchon was eager to succeed him as leader of the Quebec wing of the Conservative party, but nobody in Montreal or Quebec wanted him. Following this new disappointment he allied himself tacitly with the Liberal opposition in the House of Commons. During the Pacific Scandal he openly proclaimed his change of allegiance and became one of the bitterest foes of his former political friends.

That year Cauchon also encountered difficulties in the management of the North Shore Railway. As a result of the lobbying of several representatives from constituencies in the region between Quebec and Montreal, the company had been reconstituted in 1870 by an act which granted more land and money, and Cauchon had become its president. With characteristic vigour he devoted much energy to his task. He launched a veritable campaign in the municipalities and obtained numerous promises of subsidies from Quebec City (a sum estimated at $1,000,000), Trois-Rivières, and other localities. But he was less successful in the countryside. L’Assomption and Champlain counties, under pressure from the Ultramontanes, opposed any contributions, and thus broke the unanimity required among the north shore counties if the project were to be carried out. Specifically, the resistance was related to the proposed layout of the system, but it can be explained by differences of opinion and conflicts of interest. The aim behind the railway was to encourage trade and industry on the north shore, whereas according to the conservative ideology reigning in some regions settlement was the first priority for the provincial economy. Hence the Ultramontanes, who had been attacked by Cauchon when the Programme catholique was made public [see François-Xavier-Anselme Trudel], seized the opportunity to indulge in political revenge at the expense of the undertaking which Cauchon headed, despite its undeniable financial advantages. Nevertheless Cauchon went ahead quickly with construction, giving the contract to a Chicago firm. The latter, however, was unable to obtain the necessary capital on the London market. Consequently Cauchon once again met with a setback and himself suffered the ridicule he had so often turned against all and sundry. In May 1873 he was ousted from the company by the machinations of a group of Quebec financiers who successfully manipulated the election of the directors. James Gibb Ross, whom Cauchon had so “savagely” beaten in the preceding federal elections, became the new president.

It was, then, a man disappointed in many undertakings, embittered and more aggressive than ever, who was received into Liberal ranks at the end of 1873, during the Pacific Scandal. There is no doubt that Cauchon, in this volte-face, was an opportunist. He could not believe seriously in political liberalism. He would shortly advocate a union embracing all men of the same principles, whether Liberal or Conservative; he was even to have been the leader of this party of union, which in fact never came into existence.

However Cauchon, who was not compromised by a Liberal past and had ready access to the clerical milieux of Quebec, was of great assistance to Alexander Mackenzie*. He helped to settle the thorny issues of the general pardon for the Métis leaders, including Louis Riel, and of the New Brunswick schools. He served as an intermediary between the Liberal party and the Roman Catholic Church. Thus he helped, in particular by sending an address to Rome, to rehabilitate the party in the province. At a time when “undue influence” was raising the question of the relations of church and state in Canada, he drafted, at the clergy’s request and with the support of the Liberal members of the federal parliament, another factum which certainly influenced Rome’s attitude after the inquiry of Bishop George Conroy*. Taking into account Cauchon’s influence and experience, Mackenzie made him president of the Privy Council in December 1875. He tried in vain to appoint him minister of justice but did manage to make him minister of internal revenue on 8 June 1877. Unfortunately Cauchon, who was invariably peremptory, surly, and argumentative, quickly became a liability for the Liberal government. He was even behind the dissensions among the Quebec Liberals. Wilfrid Laurier* asserted that their happiness “will be complete when old Joe has been driven out of the temple.” With an eye to the general elections of 1878 Mackenzie therefore found himself obliged to dismiss Cauchon in order to make room for Laurier in the government and thus rebuild the unity of the party’s Quebec wing. He gave a clear explanation of this to George Brown: “I told Cauchon that I could not maintain him any longer, that his advent had done us harm everywhere; and whether just or unjust the feeling was so strong and universal against him that I had resolved not to go to the elections with him.”

Cauchon, however, was not one to submit to a rebuff without compensation, even if it meant exile: on 4 Oct. 1877 he accepted the post of lieutenant governor of Manitoba. The appointment gave rise to widely divergent comment. In the province of Quebec a few justified it on the grounds of Cauchon’s long parliamentary experience, extensive knowledge of constitutional law, and bilingualism. But in general Mackenzie was blamed for having chosen Cauchon in preference to better candidates solely in order to clean up the government in preparation for the general elections. The appointment received more criticism in Ontario. Thus in Toronto the Mail offered its sincere condolences “to the people of Manitoba, who deserve a better fate,” and the Grip likened Cauchon to an unwanted child “left on Manitoba’s doorstep by his frustrated mother, the Mackenzie administration.” In Manitoba itself Cauchon’s appointment awakened racial antagonism and sparked a nationalist quarrel between the Manitoba Daily Free Press of Winnipeg and Le Métis of St Boniface. Between 1871 and 1875 English immigration, particularly from Ontario, had steadily increased so that English-speaking people were in the majority in Manitoba and held the balance of power. There were fears among the English that Cauchon would not respect the wishes or even the laws of the majority but would work on behalf of the French-speaking minority. In short, there were fears of a dictatorship. In the French community his appointment produced “a glimmer of hope,” for, as Archbishop Alexandre-Antonin Taché* observed, “The appointment of a French Canadian is as extraordinary as the arrival of the railway.”

Cauchon took up his duties on 2 Dec. 1877. The death of his wife, Marie-Louise Nolan, four days later, subdued the critics so that he was able to begin his term of office quietly. Moreover he had the opportunity to make his peaceful intentions known: “I am not the representative of a faith or a nationality . . . . My duty is to ensure that the law is upheld, to bestow special favour on no citizen but to render justice to all.” In fact Cauchon restricted himself to the role assigned to him by the constitution. He allowed those charged with the responsibility to govern to do so and generally served as no more than the intermediary between the federal government and the province. In 1878 he reserved for the governor general’s assent the act to abolish the publication in French of the province’s official documents. Commenting on his action in a letter to Archbishop Taché, he revealed his own commitment regarding the future of French in Manitoba: “I have done all I can, I have even gone beyond my sphere in order to remedy the evil. . . . The French language is secure. For how long I do not know, for I am not sure that the Manitoba Act, which in any case is very vague, cannot be attacked by your provincial legislature when the latter desires. . . . The only remedy is an immigration of the French from Lower Canada, which the clergy should encourage with all its influence and all its energy. Is it not better that our compatriots come here rather than go to the United States?” Disappointed by what they have called a “policy of indifference,” some people, such as Frank A. Milligan in his study of the lieutenant governors of Manitoba, have seen in Cauchon a “do-nothing king,” and asserted that during his term of office the prestige of the lieutenant governor was at its lowest ebb. But the most commonly voiced reproach, namely Cauchon’s lack of influence at Ottawa, first with Mackenzie and then with Macdonald, suggests a false notion of the function of a lieutenant governor. All things considered, one can concur in Joseph Dubuc*’s judgement that “Cauchon administered the government with justice and impartiality.” He left his post on 1 Dec. 1882.

Cauchon was overtly engaged in business in Manitoba, and this activity may more deeply have shocked those who did not appreciate his discreet role in politics. He arrived in Winnipeg at the time of the economic boom resulting from the building of the railway and continued the game of speculation which had already made him rich in Quebec. According to Dubuc, he realized a profit of some $500,000. The Manitoba Daily Free Press asserted in March 1882 that it had learned from an authoritative source in Ottawa that Cauchon had already made a profit of $1,000,000. His speculation included such deals as the sale of 120 lots in three evenings for $15,243.50 at Point Douglas (now part of Winnipeg), and of 470 acres for $283,000 at St Boniface. In December 1880 he had bought a lot for $60,000 in the heart of Winnipeg, opposite the large new Hudson’s Bay Company building. On it he built a splendid four-storey edifice in Grecian style for offices and stores. Known as the Cauchon Block, it cost $100,000 to build. But caught unawares and ruined by the crash of 1882, Cauchon had to abandon his “palace” to his creditors in September 1884; he had lived in it for a few months, having decided to remain in Winnipeg at the end of his term of office. Then he retired with his son to a homestead called Whitewood in the Qu’Appelle valley. He lived there on “hard-tack and bacon,” and died on 23 Feb. 1885.

Cauchon had been married three times, a fact which prompted Robert Rumilly to remark that he had “the physique of Bluebeard.” On 10 July 1844 at Quebec he married Julie Lemieux, and they had two children, Joseph and Joséphine; then in 1866 he married Marie-Louise Nolan, and they had a son, Nolan; on 1 Feb. 1880 in Chicago, he took as his third wife Emma Lemoine of Ottawa.

Cauchon had made his will in Winnipeg on 12 Feb 1884. After disposing of personal possessions, he left his wife half his property; to his son Nolan, a minor, he bequeathed $2,500 plus a third of the balance, and the remainder was shared equally between his other two children. No notarial contract has been found of his possible assets in the province of Quebec at the time of his death. Thus his inheritance was probably limited to his Manitoba assets valued officially at $150, and to the indemnity of £1,329 12s. (or approximately $6,500) which the Colonial Life Assurance Company paid to his heirs on 26 June 1885.

More than anyone else, or at least in a more visible fashion, Cauchon stuck to intrigue, even “corrupt intrigue,” in his Journal de Québec, his political career, and his financial activities. It is beyond doubt that he knew how to reconcile his principles with his interests, that he made journalism the stepping-stone for his political career, and his political career the crossroads for his financial operations. For 30 years he was the strong man of the district of Quebec, ruling supreme in various branches of human activity. While Cauchon was studying at the Séminaire de Québec, a priest had advised him to give up his name because it left him open to ridicule, and to adopt the second family name, Laverdière. His reply was: “I shall call myself Cauchon and nothing else, and I shall force the mockers to lower their heads when [they hear] that name.” Such was the stormy life of Cauchon: a constant challenge, a ceaseless battle.

Joseph-Édouard Cauchon was the author of: Aux électeurs du Bas-Canada (Québec, 1863); Étude sur l’union projetée des provinces britanniques de l’Amérique du Nord (Québec, 1858); Notions élémentaires de physique, avec planches à l’usage des maisons d’éducation (Québec, 1841); and The union of the provinces of British North America (Quebec, 1865).

AASB, T22052–57. ANQ-Q, AP-P-134; AP-G-344. ASQ, Fichier des anciens; Fonds C.-H. Laverdière, no.54; Fonds Viger-Verreau, Sér. O. Baker Library, R. G. Dun & Co. credit ledger, Canada, 8. BE, Québec, Reg. B, 44, no.17288; 46, no.18313; 55, no.22775; 64, no.27268; 67, no.28673. PABC, Crease coll., Henry Pering Pellew Crease, Corr. inward, Sir Hector-Louis Langevin, 1872–96. PAC, MG 26, A; B; MG 27; I, C8; D4; D11; F3; MG 29, C10. PAM, MG 3, D1; MG 12, B1; C; MG 14, B26. Surrogate Court of Eastern Judicial District (Winnipeg), no.97, will of J.-É. Cauchon, 12 Feb. 1884. Alexander Begg and W. R. Nursey, Ten years in Winnipeg; a narration of the principal events in the history of the city of Winnipeg from the year A.D. 1870, to the year A.D. 1879, inclusive (Winnipeg, 1879). Can., chambre des Communes, Journaux, 1867–68, 1872–77; Parl., Doc. de la session, 1867–77; Sénat, Débats, 1868–72. Can., Prov. du, Assemblée législative, Journaux, 1844–66; Parl., Débats parl. sur la confédération. Canada Gazette, 1867–77. Québec, Assemblée législative, Journaux, 1867–74. Québec, ville de, Bureau du trésorier, Comptes (Québec), 1865–67. L’Aurore des Canadas (Montréal), 8 nov. 1842. Le Canadien, 1841–42. Le Courrier du Canada, 1857–58, déc. 1867, 1873, févr. 1885. Le Journal de Québec, 1842–89. Manitoba Daily Free Press, 20 Aug. 1881, 1 March 1882. Le Métis (Saint-Boniface, Man.), 1877–85. Le Nouvelliste (Québec), 26 févr. 1885. La Patrie, 28 févr. 1885. Le Pays (Montréal), juin 1855, déc. 1867. Achintre, Manuel électoral. Beaulieu et J. Hamelin, Journaux du Québec; La presse québécoise, I: 123–26. Charles Beaumont, Généalogie des familles de la côte de Beaupré (Ottawa, 1912). Dent, Canadian portrait gallery, IV: 138–44. J. Desjardins, Guide parl. DOLQ, I: 738–39. Encyclopedia Canadiana, II: 289. Le Jeune, Dictionnaire, I: 329. The makers of Canada; index and dictionary of Canadian history, ed. L. J. Burpee and A. G. Doughty (Toronto, 1911). Morgan, Sketches of celebrated Canadians, 609–12. J. P. Robertson, A political manual of the province of Manitoba and the North-West Territories (Winnipeg, 1887). P.-G. Roy, Les avocats de la région de Québec, 83. Cyprien Tanguay, Dictionnaire généalogique des familles canadiennes depuis la fondation de la colonie jusqu’à nos jours (7v., [Montréal], 1871–90), I: 133–34. Dom [J.-P.-A.] Benoît, Vie de Mgr Taché, archevêque de Saint Boniface (2v., Montréal, 1904). Careless, Union of the Canadas. Chapais, Hist. du Canada, V–VIII. F.-X. Chouinard et Antonio Drolet, La ville de Québec, histoire municipale (3v., Québec, 1963–67), III. Cornell, Alignment of political groups. L.-O. David, Au soir de la vie (Montréal, [1924]); L’Union des deux Canadas, 1841–1867 (Montréal, 1898). Alfred Duclos De Celles, Cartier et son temps (Montréal, 1913); La Fontaine et son temps (Montréal, 1912). Désilets, Hector-Louis Langevin. M. Hamelin, Premières années du parlementarisme québécois. F. A. Milligan, “The lieutenant-governorship in Manitoba, 1870–1882” (ma thesis, Univ. of Manitoba, Winnipeg, 1948), 230–45. Rumilly, Hist. de la prov. de Québec, I–III. Soc. hist. de Saint-Boniface, Les francophones dans le monde des affaires de Winnipeg, 1870–1920(Saint-Boniface, 1974). L.-P. Turcotte, Le Canada sous l’Union. P. B. Waite, Canada, 1874–1896; arduous destiny (Toronto and Montreal, 1971). B. J. Young, Promoters and politicians: the North-Shore railways in the history of Quebec, 1854–85 (Toronto, 1978). Andrée Désilets, “Une figure politique du XIXe siècle; François-Xavier Lemieux,” RHAF, 20 (1966–67): 572–99; 21 (1967–68): 243–67; 22 (1968–69): 223 55. “Feu l’honorable Joseph Cauchon,” Rev. canadienne, 21 (1885): 177–81. “Les maires de Québec de 1833 à 1894,” La Presse, 31 mars 1894. F. [A.] Milligan, “Reservation of Manitoba bills and refusal of assent by Lieutenant-Governor Cauchon, 1877–82,” Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science (Toronto), 14 (1948): 247–48.

Cite This Article

Andrée Désilets, “CAUCHON, JOSEPH (baptized Joseph-Édouard),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cauchon_joseph_edouard_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cauchon_joseph_edouard_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Andrée Désilets |

| Title of Article: | CAUCHON, JOSEPH (baptized Joseph-Édouard) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |