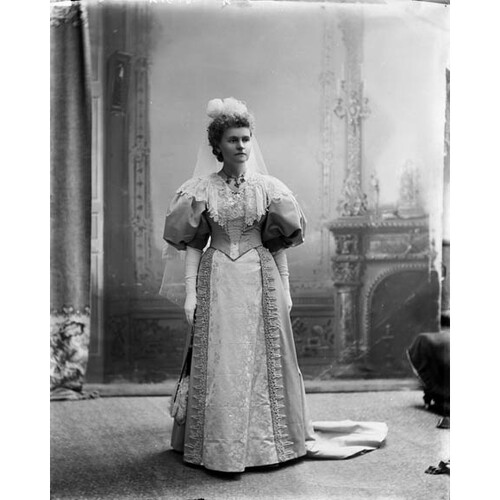

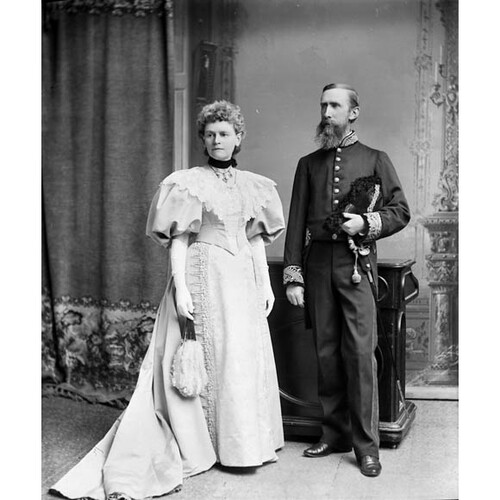

DAVIS, ADELINE (Chisholm; Foster, Lady Foster), temperance reformer and author; b. 14 April 1844 in Hamilton, Upper Canada, eldest daughter of Milton Davis, a stagecoach proprietor, and Hannah Cook; m. first 17 Aug. 1864 Daniel Black Chisholm in Hamilton, and they had a son and a child who died in infancy; m. secondly 2 July 1889 George Eulas Foster* in Chicago; they had no children; d. 17 Sept. 1919 in Ottawa.

As a young woman, Addie Davis studied at the Genesee Wesleyan Seminary in Lima, N.Y., where she was said to be distinguished for her “diligence, aptitude, and general proficiency.” After graduation, she taught an infants’ class in one of Hamilton’s Methodist Sunday schools, possibly at Centenary Methodist Church. The school superintendent there was D. B. Chisholm, a prominent barrister, whom Addie married in 1864. Although they shared many interests, including temperance and public life – Daniel was a councillor and mayor of Hamilton, and then an mp – their marriage was not a happy one. In September 1883, according to Addie, Daniel deserted her and their young son and left Hamilton, apparently because he had misappropriated clients’ funds. By 1885 Addie Chisholm had moved to Ottawa and seems to have been renting out rooms in her residence at 127 Bank Street. One of her lodgers was George E. Foster, a temperance advocate and a Conservative mp. A relationship between the two soon started.

Publicly throughout the 1880s Addie Chisholm devoted herself to temperance, a cause she had taken up in earnest in Hamilton. She was second president of the Ontario Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, from 1882 to 1888, and publisher and editor of the WCTU periodical, the Woman’s Journal (Ottawa), in 1885. As well, she authored a number of tracts and pamphlets for Ontario WCTU officers and youth-group leaders. A strong-willed and unfailingly hard worker, she was an important mover in organizational committees for provincial conventions, helped set up local unions, and was a noted platform speaker. In 1888 she was the Canadian representative at the meeting of the National WCTU in the United States. In Ontario she supported the female franchise as a key step to obtaining legislated prohibition: “The Lord never promises to do for us what we can do for ourselves, and we have come to the conclusion that this stone of woman’s disability is to be rolled away before prohibition will come to this country.”

Like Letitia Youmans [Creighton*], the first president of the Ontario WCTU, Chisholm was devoutly evangelical. She was certain that WCTU efforts would find success if members pledged themselves to the proposition “that our diffidence in speaking at the great truths which lie so near our hearts may be overcome in the strength of Him who will give us the victory.” She apparently saw Youmans, whose presence steeled “less gifted and more timid” members, as her mentor. Following Youmans’s example, Chisholm was a firm proponent of temperance education for juveniles through bands of hope and loyal temperance legions. These were groups of children, from about 7 to 12 years of age, who met after school and on Saturdays. A single mother, Chisholm was an implacable supporter and defender of the Young Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, a WCTU subgroup for single women of about 16 and older. Its existence was controversial because many in the Ontario WCTU feared that the youth group would draw members from the main body and thus weaken the common cause. There was also jealousy in the ranks over the range and success of many YWCTU initiatives, including homes for unwed and abandoned mothers, residences for working women, temperance and gospel missions among the poor, and literacy programs for working-class girls and boys.

Under Chisholm’s direction, the Ontario WCTU continued its campaign to have “Scientific Temperance Instruction” made compulsory in the public schools. Such instruction emphasized the terrifying physical effects of alcohol and tobacco on the unsuspecting user. Chisholm argued, as Youmans had before her, that the course must be supported by a WCTU-approved textbook, properly trained teachers, and final examinations. Partly through the work of Chisholm and such other WCTU leaders as Emma Frances Jane Pratt [Vail], the subject was introduced into Ontario schools on an optional basis in 1885, part of the moral thrust being introduced by education minister George William Ross. (The course would become compulsory eight years later.)

In January 1888 Addie Chisholm moved from Ottawa to Chicago, where a brother lived, no doubt to obtain an easy divorce. In the same year she and George Foster became engaged, but securing a divorce in Ontario meant petitioning the Senate, an expensive course that might also have done political harm to Foster, who became minister of finance in May 1888. Proceedings were therefore instituted in the Circuit Court of Cook County in January 1889. As a result, Addie resigned that year from the Ontario WCTU.

On the occasion of her final address to its annual convention, she was treated to an extended and emotional tribute. From this and other statements made about her, additional insight can be gained into her personal qualities. Many referred to her warmth and “Christian gentleness and kindness.” There is also evidence of her assertiveness, for it seems that within the Ontario WCTU her views generally prevailed. In her speech to its delegates, she noted that “even when my plans ran counter to your own you have been ever ready to renounce the one and embrace the other.” There can be no doubt about the strength of her personality. For a single parent to lead an organization committed to the preservation of family must have demanded enormous strength, but to divorce, in 19th-century Canada, required even more fortitude.

Addie’s divorce was granted in June 1889 and Foster quickly joined her in Chicago, where they were married. Repercussions started as soon as they returned to Ottawa. Many questioned the legal validity of the divorce in Canada, and the Fosters were officially shunned. The prime minister’s wife – the iron-mannered Lady Macdonald [Bernard] – and Governor General Lord Stanley* both refused to receive Addie Foster. Sir John A. Macdonald* feared personal attacks against his cabinet colleague in the House of Commons, and on the hustings in the election of 1891 hecklers hurled the Chisholm name at him. The Fosters were accepted, however, by Sir John Sparrow David Thompson*, the minister of justice and later prime minister, who reputedly considered the divorce legitimate, and by Lady Thompson [Affleck]. In 1893 the ostracism ended when the Fosters were invited to a concert put on by Governor General Lord Aberdeen [Hamilton-Gordon*] and Lady Aberdeen [Marjoribanks*].

Following her marriage and return to Ottawa, Addie eventually shifted her energies from temperance to more fashionable cultural and humanitarian pursuits. After 1900 she was active with the Women’s Canadian Historical Society, the Ottawa Humane Society, the Women’s Morning Music Club, the Women’s Canadian Club, and the Ottawa branch of the Victorian Order of Nurses. Understandably, a good deal of her time also went into making social contributions to the career of her husband, who was knighted in 1914.

Lady Foster died in 1919 after a two-year battle with breast cancer, discreetly described in an obituary as a “mortal but lingering illness.” Deeply depressed, her husband painfully marked her passing in his diary: “Dull without and dark within.”

Addie [Davis] Chisholm is the author of Why and how: a handbook for the use of the W.C.T. unions in Canada (Montreal, 1884).

AO, F 885, MU 8404, 8407–9; RG 80-8-0-14, no.10898. Circuit Court of Cook County Arch. (Chicago), divorce file no.71298. NA, MG 27, II, D7, vols.11, 109; RG 31, C1, 1871, Hamilton, Ont., St Andrew’s Ward, div.1: 19 (mfm. at AO). Hamilton Spectator, 18 Aug. 1864. Ottawa Evening Journal, 4 July 1889; 17, 20 Sept. 1919. Canadian biog. dict. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.2. Directory, Ottawa, 1882–1919. [I. M. Marjoribanks Hamilton-Gordon, Marchioness of] Aberdeen [and Temair], The Canadian journal of Lady Aberdeen, 1893–1898, ed. and intro. J. T. Saywell (Toronto, 1960). Waite, Man from Halifax. W. S. Wallace, The memoirs of the Rt. Hon. Sir George Foster, p.c., g.c.m.g. (Toronto, 1933).

Cite This Article

Sharon Anne Cook, “DAVIS, ADELINE (Chisholm; Foster, Lady Foster),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 15, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/davis_adeline_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/davis_adeline_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Sharon Anne Cook |

| Title of Article: | DAVIS, ADELINE (Chisholm; Foster, Lady Foster) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | April 15, 2025 |