Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

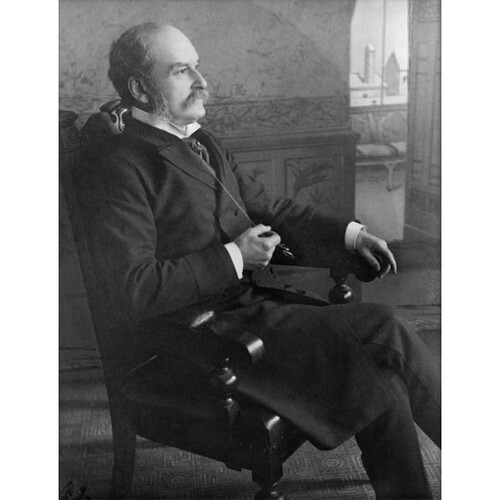

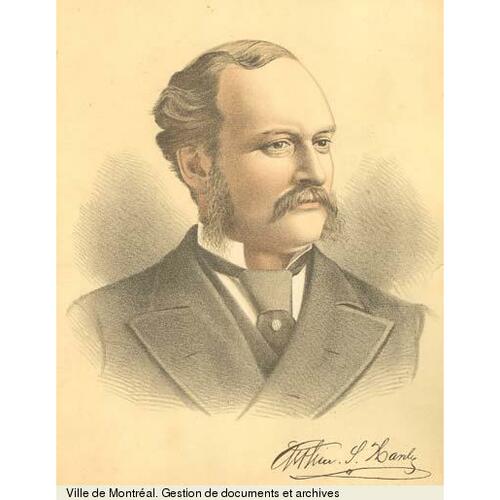

HARDY, ARTHUR STURGIS, lawyer and politician; b. 14 Dec. 1837 in Mount Pleasant, Upper Canada, son of Russell Hardy and Juletta Sturgis; m. 19 Jan. 1870 Mary Morrison, daughter of Joseph Curran Morrison*, and they had three sons and a daughter; d. 13 June 1901 in Toronto.

The Hardy and Sturgis families were among the first white settlers of Brant County. Russell Hardy was a farmer, although for short periods of time he ran a general store in Mount Pleasant and then in nearby Brantford. His son Arthur received a sound education, attending the private academy run in Mount Pleasant by the Reverend W. W. Nelles, the Brantford Grammar School, and William Wetherald*’s Rockwood Academy. After his schooling, he read law in the Brantford office of his uncle, Henry A. Hardy, and with the Toronto firm of Robert Alexander Harrison*. Hardy became a solicitor in 1861 and was called to the bar in 1865. He practised first in partnership with his uncle, but in 1867 he set up his own firm in Brantford. His practice flourished, earning him a local reputation as a skilled attorney in civil and criminal proceedings. He became town solicitor for Brantford in 1867, a bencher of the Law Society of Upper Canada in 1875, and a qc the next year.

In Toronto as a law student, Hardy had acquired political experience working on George Brown*’s election committees. On his return to Brantford, he became active in the local Reform Association. For business reasons he declined the Liberal nomination for Brant North in the 1872 federal election, but the following year, when Edmund Burke Wood* resigned the seat for Brant South in the provincial legislature, Hardy won the by-election.

Hardy soon made his mark in provincial politics. His indefatigable energy, legal skill, and aggressive debating style, which on occasion was more vicious than logical, were rewarded with an appointment to the cabinet as provincial secretary on 19 March 1877. He filled that position until 18 Jan. 1889, when he became commissioner of crown lands. In these posts he not only added substantially to the legislative record of Premier Oliver Mowat’s government (he reputedly introduced 150 public and private bills, many of them amendments), but he also paid careful attention to those pragmatic and occasionally unpleasant details of politicking so essential to his party’s longevity in office. To the Toronto Mail, Hardy was “the party virago,” who “invariably makes it his business to do the greater share of the abusive work.”

Greater skill was required of Hardy than the Mail was prepared to credit. As provincial secretary, he introduced or handled many of the measures that Mowat promoted to centralize authority and power in the provincial government. Most significantly, the Liquor Licence Act of 1876, introduced by Adam Crooks*, had taken responsibility away from municipal councils and given to the Liberal government the regulation of what had long been a critical lubricant for the Conservative machine. In administering the act, Hardy consulted both temperance and liquor interests, apparently neither offending nor fully satisfying either, and introduced progressively stricter provisions in 1881, 1884, and 1886. He knew, however, that the real importance of the act was political. One of his first decisions as provincial secretary was to send the whisky detectives into his own riding in September 1877 to enforce the Dunkin Act, under which Brant County’s voters had favoured prohibition. Brantford’s “low grocers” and its hotel- and saloon-keepers, licensed or not, had been accustomed to marshalling voters and dispensing election-day drinks, which usually produced a Conservative majority in the city polls. When over 100 charges were laid, a mob drove the detectives out of town before the cases could be brought to trial. Following the riot Hardy compromised by reducing the charges in return for guilty pleas. In any case, he had made his point by demonstrating his ability to harass the minions of his political opponents. Throughout the province the licensing act proved a useful tool for partisan advantage.

In his first cabinet post Hardy was responsible for other measures enhancing the government’s ability to use patronage. His civil service reform bill of 1878 standardized the organization of provincial departments and employment within them, an initial step to managing government appointments. In 1882 he introduced the bill creating a permanent board of health, which required the appointment of a whole new category of provincial inspector, and named its first secretary, Peter Henderson Bryce*. Hardy appointed a variety of other officials, all of whom might use their power to reward the faithful.

As commissioner of crown lands from 1889 to 1896, Hardy took over the major source of revenue for the Mowat government, the sale of timber concessions, especially in the north. His efforts to generate substantial new revenue from mining, however, proved unfruitful. In the late 1880s and early 1890s the industry remained largely undeveloped, though by 1891 Hardy believed that nickel was becoming so valuable [see Samuel J. Ritchie] that it might “afford a revenue . . . which will ward off the bugbear of direct taxation.” The royal commission on mineral resources in 1890 recommended development policies which favoured the industry, but the legislation introduced by Hardy the next year incorporated only the proposals to disseminate knowledge about resources and technology through a bureau of mines. Rejected was the suggestion that the government should forgo royalties and sell, rather than lease, mining lands to stimulate the industry. The charges to be imposed under the proposed act provoked the condemnation of mining promoters, including Liberal mpp James Conmee* of Algoma West, and their lobbying forced a reduction in the charges.

The importance of crown lands for revenue made Hardy ambivalent about conservation. On the one hand, he was responsible as commissioner for the creation of the province’s first wilderness parks, Algonquin (1893) [see Alexander Kirkwood] and Rondeau (1894). On the other hand, he baulked at opposition demands for a reforestation policy because of its expense and prevaricated by asserting that Ontario’s timber reserves would last a century.

When Mowat retired in 1896, Hardy as the senior minister became the new premier and attorney general, on 21 July. He had hesitated, knowing that his diabetes and his age, 58 years, made his health uncertain but, as he confessed to John Stephen Willison*, “you know how very difficult it is in this wicked world to let high honours pass.” Aware of his weakness, he relied heavily on his minister of education, George William Ross*. At first he called his administration “the Hardy-Ross Government” but, following opposition criticism of “this double-headed thing,” the name was dropped.

The Hardy government lasted just four parliamentary sessions, until the fall of 1899. Its most significant and controversial legislation declared the “manufacturing condition” as a principle in provincial resource policy. In December 1897 Hardy introduced an amendment to the Crown Timber Act requiring that after 30 April 1898 all pine cut under licence on crown lands be sawn into lumber in Canada. The log act was a somewhat reluctant response to the uproar raised by the Ontario Lumbermen’s Association over the American Dingley tariff of 1897, which had placed restrictive tariffs on sawn lumber but allowed free import of sawlogs [see John Bertram]. His defence of capital and sawmilling jobs in Ontario proved to be more popular politically than he had expected, but Hardy correctly anticipated pressure from American business and the dominion government.

Michigan lumbermen lobbied the Canadian government and persuaded the American secretary of state to intercede on their behalf with the British ambassador in Washington. Ontario, they argued, had breached its contracts with them by imposing new regulations. Moreover, they claimed that the log act intruded upon federal jurisdiction over trade and commerce and should therefore be disallowed. The Liberal government of Sir Wilfrid Laurier* dismissed the constitutional issue, agreeing with Hardy that the province was free to set whatever regulations it chose for its crown lands. At the same time, Richard William Scott*, Laurier’s secretary of state, advised the premier that the possibility of disallowance could be used as a tool in negotiating a reciprocity treaty. Laurier, hoping to deflect American pressure, wanted Hardy at least to submit the act to the courts for a judgement on the breach-of-contract charge. Hardy bluntly refused both suggestions. As a provincial election approached, the act was too important politically.

The simultaneous existence of Liberal governments in Ottawa and Toronto from 1896 complicated Hardy’s administration, since each level expected the other to help contain difficult political situations. For example, when Manitoba’s abolition of public funding for Catholic schools [see Thomas Greenway] threatened to weaken Catholic support for the Liberal party, Laurier urged Hardy in 1896 to reassure French-speaking Catholics by appointing their spokesman, François-Eugène-Alfred Évanturel, if not to a cabinet posting then at least to the speaker’s chair. Because of competing ambitions within his own caucus, Hardy hesitated before accepting the latter recommendation. In turn he expected Laurier’s government to direct more patronage appointments and honours to Ontario Catholics and he complained when its liberality seemed lacking.

The weakening of Catholic favour troubled Hardy going into the 1898 election. Campaigning on the record of “26 years of progressive legislation and honest administration,” he hoped to recoup the traditional support among farmers that Mowat had lost to the Patrons of Industry in 1894 [see George Weston Wrigley]. He won 51 seats, a majority of only 7. The Conservatives made remarkable gains under James Pliny Whitney* and picked up 16 seats. Hardy thought that, although he had split the former Patron and independent vote with the Conservatives, his rivals had gained among the Catholics, enjoyed solid backing from the liquor interest, and most significantly had taken a larger share of “new” urban voters, especially “the dregs of the cities and country towns.”

The results surprised both parties. Hardy wanted to call another election but was dissuaded by his ministers. The Conservatives believed that more money would have given them an upset. Whitney, seeing victory so close, refused the convention of dropping one contested election in return for the Liberals abandoning another. Consequently, the results in 65 of the 94 seats were appealed by the two parties. The Conservatives, falling upon an inspired tactic, argued that the votes of the special constables hired by the government to attend the polls, several thousand votes in all, contravened the election act. Were these ballots disallowed, several ridings might swing to the Conservatives.

On the advice of Mowat, then lieutenant governor of Ontario, Hardy submitted the question to the Court of Appeal, which refused to hear the case during its summer recess. Rather than wait, he called the legislature into early session, ostensibly to deal with other pressing matters. At first Hardy contemplated passing retroactive legislation declaring the legality of the constables’ votes. He reconsidered, however, and the house passed legislation which deferred to the court, with the proviso that if the votes were judged illegal, then by-elections would be held. In September the court rendered the legislation moot when it affirmed the constables’ franchise.

Hardy’s narrow majority nevertheless remained under pressure since election trials, a death, a resignation, and a cabinet appointment necessitated ten by-elections in late 1898 and early 1899. The Liberal leadership in general had attributed considerable responsibility for the poor showing in the election to inadequate organization, so Hardy brought Mowat’s former organizer, William Thomas Rochester Preston*, out of political retirement to handle the by-election campaigns. As he told Laurier, Preston “could take hold and shake up the whole country . . . as no other half dozen men I know of could.” Indeed, he delivered eight ridings.

But the victories were soon clouded by charges of corruption. Conservative protests revealed that in Ontario South, where John Dryden won re-election, and in Elgin West, where Donald Macnish was successful, Preston’s machine had hired impersonators to cast votes and had used bogus deputy returning officers to manipulate the ballots. Several of those involved, besides being Liberal workers, were in the government’s employ. Whitney exploited the issue fully. Despite Preston’s denials of guilt, party insiders, such as John S. Willison and David Mills, were convinced that fraud had become, in the latter’s words, one “of the new methods adopted in political contests.” No one impugned Hardy’s personal honesty, though his government was decried for allowing such practices to occur.

The stress of the 1898 campaign and of containing the damage from the constables’ question and the by-election scandals took their toll on Hardy’s already weak health. On the advice of his doctor, he stepped down from the premiership on 20 Oct. 1899, resigned his seat, and accepted the sinecure of clerk of the process and surrogate registrar at Osgoode Hall in Toronto, a petty office after such a distinguished career. His health did not permit a more demanding or higher-paying position. Until his friends, including Willison and George Albertus Cox*, raised a retirement fund of $20,000 for him, his financial security remained a concern. As well, the events preceding his departure from public life weighed heavily upon his spirits. Without his knowledge, one of his sons and his brother Alexander David pressed Willison to ask Laurier to obtain a knighthood for Hardy. One had been in the offing in 1897 but, knowing the democratic preferences of his rural constituents, Hardy had informed Laurier that he would decline an honour he felt to be a political liability. The offer was not made a second time. Hardy died in Toronto in 1901 following an operation to remove a ruptured appendix. An Anglican, he was buried with masonic rites in Greenwood Cemetery in Brantford.

Arthur Hardy’s reputation has remained under a cloud because of electoral corruption during his term of office and the long decline of his party thereafter. But Liberalism’s problems in Ontario owed more to a changing economy and demography than to a newfound revulsion over what had long been common political practice. Rather, Hardy should be considered in light of his contribution to the longevity of Mowat Liberalism, specifically his role in assembling a political machine and in administering a fiscal policy that exploited northern resources to cover expenditures throughout the province. Orlando Q. Guffy, Grip’s fictitious Queen’s Park parliamentarian, understood Hardy’s importance as a hard-nosed and down-to-earth politician in Mowat’s service: “The more wickeder he is, playing euchre and swearing and entertaining thirsty strangers, the brighter does the virtue of Mowat shine by contrast.” The two roles complemented each other; when Mowat left, Ontario Liberalism lost its moral gloss.

Hardy’s official publications for the Ontario Attorney General’s Dept. include In the matter of the correspondence of Michigan lumbermen respecting timber licenses and their manufacturing conditions imposed by regulations and the act 61 Vict., cap. 9, Ontario statutes . . . ([Toronto?, 1898]) and Meeting of the Ontario Legislature: memorandum by the attorney general to the lieutenant governor in council; submitted July 12, 1898 ([Toronto, 1898]).

AO, F 4; RG 53, ser.20, reg.1: 4. NA, MG 26, G; MG 27, II, D14; MG 30, D29. Daily Courier (Brantford, Ont.), 27 Dec. 1886, 21 May 1890. Daily Expositor (Brantford), 14, 21 Sept., 28 Nov. 1877; 15 March 1878; 6 June 1879; 7 March 1883; 24, 29 Dec. 1886; 6 June 1890; 7 Dec. 1900. C. R. W. Biggar, Sir Oliver Mowat . . . a biographical sketch (2v., Toronto, 1905). Charlesworth, Candid chronicles. A. M. Evans, Sir Oliver Mowat (Toronto, 1992). C. W. Humphries, “Honest enough to be bold”: the life and times of Sir James Pliny Whitney (Toronto, 1985). Nelles, Politics of development. Ontario, record of the Liberal government: 26 years of progressive legislation and honest administration,1872–1898 (Toronto, 1898). F. D. Reville, History of the county of Brant (2v., Brantford, 1920). Joseph Schull, Ontario since 1867 (Toronto, 1978). D. O. Trevor, “Arthur S. Hardy and Ontario politics, 1896–1899” (ma thesis, Univ. of Guelph, Ont., 1973). Willison, Reminiscences.

Cite This Article

David G. Burley, “HARDY, ARTHUR STURGIS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 1, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hardy_arthur_sturgis_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hardy_arthur_sturgis_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | David G. Burley |

| Title of Article: | HARDY, ARTHUR STURGIS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | April 1, 2025 |