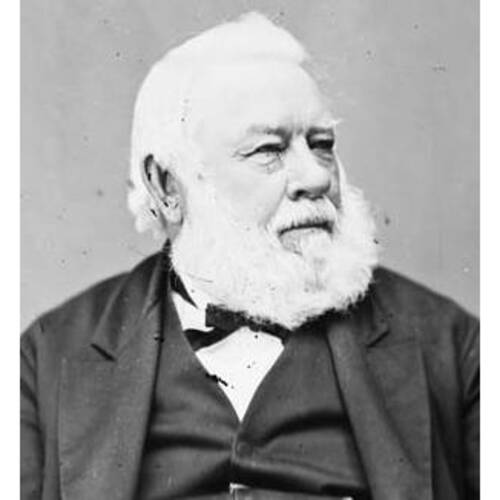

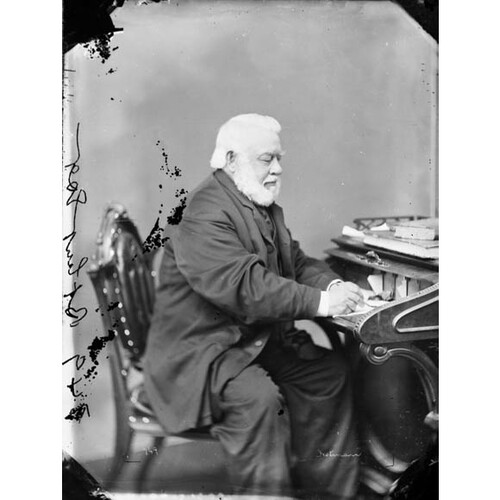

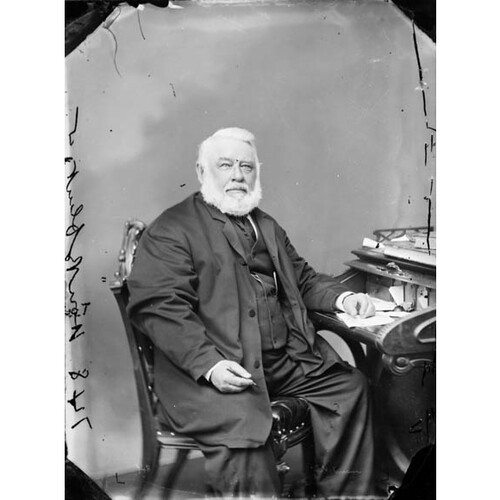

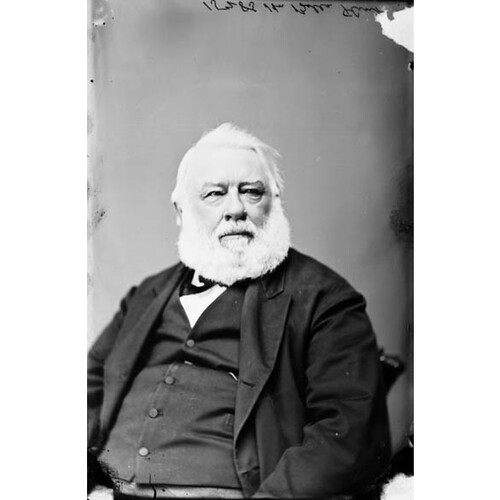

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

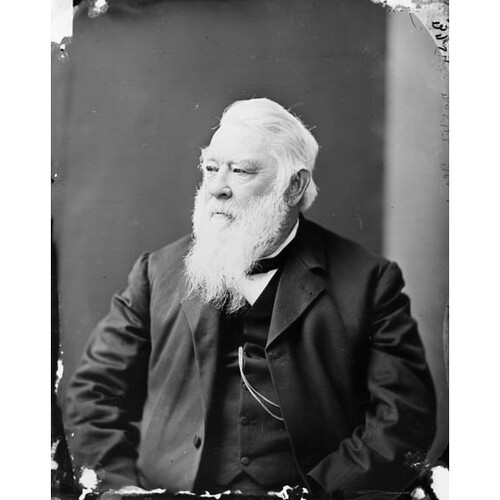

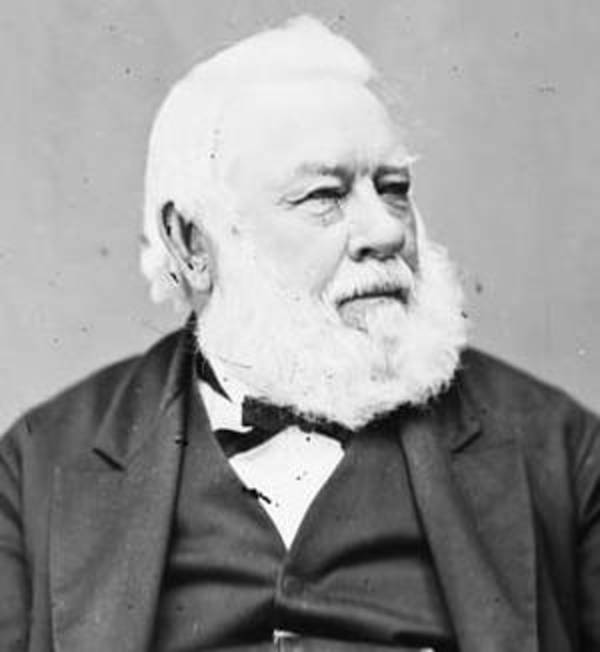

FLINT, BILLA, businessman, jp, office holder, militia officer, politician, and philanthropist; b. 9 Feb. 1805 near Elizabethtown (Brockville), Upper Canada, son of Billa Flint and Phoebe Wells; m. 10 Sept. 1827 Phoebe Sawyer Clement in Brockville, and they adopted a child, John James Bleecker; d. 15 June 1894 in Ottawa.

Billa Flint had only six weeks of school before starting work, at age 11, with his father, a boisterous Brockville merchant and hotel-keeper who had emigrated from the United States. Unlike his father, who was a hard drinker and, in later life, an opium user, the young clerk took up temperance. In 1827 two Montreal churchmen, a Mr Arble and Joseph Stibbs Christmas of the American Presbyterian Church, visited Brockville, where they received pledges from Flint and four others, including Adiel Sherwood*, to start a temperance society there. Flint later claimed it was the first in Upper Canada. Objecting to the sale of liquor at his father’s store, he left in 1829 to set up business for himself in Belleville, in Hastings County on the Bay of Quinte.

Starting as a general merchant in rented quarters, by 1837 he had transformed the entrance of the Moira River with new wharfs and warehouses and one of the province’s first steam sawmills. Drawing agricultural and forest resources from the hinterland, he was quick to attach himself to American markets via Oswego, N.Y., and the Erie Canal. His early success was reflected in 1836 in his being appointed a magistrate and made president of Belleville’s Board of Police. When rebellion broke out the following year he served as commissary of the 1st Regiment of Hastings cavalry; he later put in a claim for rebellion losses. He was an apparent target of Cornelius Parks, who stated at his trial for treason in 1839 that Flint had been on a death list.

Described in an obituary by Senator Mackenzie Bowell* as “a man of great energy, and strong feeling, no matter which side he took, whether in politics, social life or religious questions,” Flint made an early impact on the social life of Belleville as the founder of a temperance society in 1829 and as a principal founder of the Canadian Temperance League by 1845. For 21 years he was superintendent of the Bridge Street Methodist Church Sunday School. After he and a group of other trustees of this Wesleyan Methodist church prohibited access by Methodist Episcopal adherents in 1834, he was defended by William Henry Draper* in a celebrated court-case held in Kingston in 1837. The Wesleyans lost but won on appeal in 1840.

Flint’s exploitation of the Moira’s hinterland was carried north to the Skootamatta, a tributary in Elzevir Township, where in 1853 he began developing mill-sites at Troy (later named Bridgewater and now Actinolite). By 1860 he had flour-, oat-and barley-mills, a sawmill, a cabinet and chair factory, a general store, and a temperance hotel. Farther upstream, in Kaladar Township, a town-site was laid out along with a flour-mill, a sawmill, and machine shops, the nucleus of Flint’s Mills (Flinton). Sometimes in partnership with relatives, such as the Holden family, or with other businessmen, including Horace Youmans (Yeomans), Flint tackled the forest frontier in competition with other holders of large timber limits, among them Hugo Burghardt Rathbun and his son Edward Wilkes* of Deseronto and the firm of Allan Gilmour at Trenton. The small gold-rush of 1866–67 in Madoc Township prompted Flint to speculate in mining ventures in nearby Elzevir. A marble quarry near Bridgewater achieved some success, but failures with such enterprises as a gold-quartz mill and crusher at the same place and the Flint and Merrill Bronze Mining Company limited his growth.

A tireless promoter of and speculator in transportation schemes by water, road, or rail, Flint facilitated his own trade to Oswego by operating the Moira and by investing in other steamship companies along the north shore of Lake Ontario. As well, in 1837 he petitioned for improvements to the St Lawrence River and in 1868 he headed a delegation to promote the construction of a channel between the Bay of Quinte and Wellers Bay (the Murray Canal). He arranged the building of a road linking his Skootamatta mill-sites to the Addington Road. Flint was a major player from 1865 in promoting a railway between Belleville and Marmora via Tweed and Bridgewater; when the Grand Junction Railway was built in the 1870s he must have been disappointed that it did not follow his intended path. The failure of the Toronto and Ottawa Railway, which was attempting in the early 1880s to build an east-west line parallel to the Ontario and Quebec Railway, was serious for Flint because it left Bridgewater with only a spur to the Midland Railway and a monument of unused bridge pylons across the river.

As a result of either strained capital flow for ventures in northern Hastings County or the failure of the gold-rush to pan out, Flint’s Belleville mill and store were put up for sale in 1868; they passed to his adopted son and Charles P. Holton by 1873. The tentacles of Flint’s interests reached the York River in the Madawaska valley via the Hastings Road. By 1877 he had acquired the mills owned by James Cleak at York Mills and in 1879 he succeeded in having this village renamed Bancroft in honour of his mother-in-law, Elizabeth Ann Bancroft. However, fires, railway failures, and advancing age contributed to Flint’s selling his Skootamatta properties by 1883 and largely retiring from active business.

Flint’s withdrawal occurred at a time when attempts by entrepreneurs to cross the watershed to reach the Madawaska and other rivers flowing into the Ottawa valley were proving to be expensive. With little merchantable timber in the hinterland of Hastings, nothing was left to sustain Flint’s communities there. It became a land “where the young leave quickly,” as in Al Purdy’s 1965 poem “The country north of Belleville.” The assault on the Moira’s watershed had been so extensive that as early as 1869 Flint could write, “The Pine and other timber on the Moira and its tributaries is fast passing away and will soon become a matter of history.” In the words of poet Stuart MacKinnon in his 1980 book Mazinaw, “everything was up for grabs, / and Billa knew how with both hands.”

Flint had been very active in politics. He served as reeve of Elzevir Township between 1858 and 1879, reeve and mayor of Belleville in 1866, and warden of Hastings County in 1873. He was elected to the Legislative Assembly in 1847 for Hastings; defeated in 1851, he was elected in 1854 for Hastings South. A candidate for the Legislative Council in 1861 in the Trent Division, he was defeated by Sidney Smith* but won the seat in 1863. Although he voted against confederation in 1865 because of his opposition to separate schools, government financing of the Intercolonial Railway, and a non-elected senate, in 1867 he was nevertheless called to the Senate of Canada, where he served until his death more than a quarter of a century later. In 1848 the Kingston British Whig had called Flint a “loose fish,” neither reform nor conservative, but in a biographical sketch in 1880 he was described as a “life-long, inflexible Liberal.” In 1894 Mackenzie Bowell depicted him as a “Baldwin Reformer” before confederation but thereafter as one of his supporters and in accord with the Liberal-Conservative party, except that “he always delighted in calling himself a Liberal in politics.”

Behind the forceful, insistent personality of “ruddy-faced” Billa Flint, there was a softer image of a man children frequently mistook for Santa Claus because of his friendly attention and long, white beard. According to Senator Richard William Scott*, he was “a man that always regarded everything from the standpoint of morality and religion” and was either a friend or an enemy. As a philanthropist Flint donated lands for churches and schools, and he was an original supporter of social worker Annie Macpherson who in 1869 opened a distributing home, Marchmont, for child emigrants from British cities. He was behind many causes of a commercial or social nature; in 1865 Flint, Bowell, Henry Corby*, and others founded Belleville’s Board of Trade and in 1869 Flint promoted the setting up of a blast-furnace in the town.

Billa Flint died in 1894, at the age of 89, while working on Senate business in Ottawa. The Belleville Weekly Intelligencer summed up his contribution to public life: “Few men have had a more prominent connection with public affairs in this district than Mr. Flint. His career was a stormy one . . . and he dearly loved a controversy especially on a political or religious subject.”

Billa Flint was himself an active historian and biographer. His series of articles on early Belleville was published under the title “Forty years ago” in the Belleville Daily Intelligencer, 20, 27 July, 4, 10, 18, 24, 31 Aug., 7, 14, 21, 29 Sept. 1869; the series also appeared in the Globe, the Montreal Gazette, and the Montreal Herald. Further reminiscences by Flint may be found in the weekly Intelligencer: “Forty-seven years a resident of Belleville” (21 July 1876) and “Fifty years ago today” (8 Nov. 1872). A second article entitled “Fifty years ago today” was published in the Daily Intelligencer, 19 July 1879.

Belleville Public Library, Rebellion losses claims. Lennox and Addington County Museum (Napanee, Ont.), Lennox and Addington Hist. Soc. Coll., Benson family papers: 2755–58; T. W. Casey papers: 11271–72. NA, RG 5, A1: 11758–61; RG 68, General index, 1651–1841: 496. QUA, 2056, box 107. Can., Senate, Debates, 1894: 563–64. Methodist Episcopal Church in Canada, Report of the trial of an action brought by John Reynolds; and others on the part of persons calling themselves the Methodist Episcopal Church in Canada, against Billa Flint and others, trustees of the Wesleyan Methodist Church in Belleville, to obtain a chapel in the possession of the latter in the town of Belleville, by Harvey Fowler, with brief notes and remarks by E. Ryerson (Toronto, 1837; copies at Queen’s Univ. Library, Special Coll. Dept., Kingston, Ont., and Victoria Univ. Library, Toronto). British Whig (Kingston), 2 May 1834; 18 May, 10 Nov. 1836; 1, 9 Jan. 1848. Brockville Evening Recorder, 18 June 1894. Brockville Recorder, 7 Oct. 1852. Chronicle & Gazette (Kingston), 26 Oct. 1834; 9 March, 3 Sept. 1836; 1 Feb., 19 April, 11 Oct. 1837. Daily British Whig, 18 June 1894. Daily Intelligencer, 1867–79. Hastings Chronicle (Belleville), 19 Oct. 1859, 21 Aug. 1861, 18 Sept. 1865. Intelligencer (weekly ed.), 28 Dec. 1866; 26 June, 28 Aug. 1868; 13 Sept. 1877; 14, 21 June 1894. Canadian biog. dict. Canadian directory of parl. (Johnson). Hastings County directory, 1860–61, 1868–69. G. E. Boyce, Historic Hastings (Belleville, 1967). Jean Holmes, Times to remember in Elzevir Township (Madoc, Ont., 1984). W. L. Lessard, “The history of Kaladar and Anglesea townships” (typescript, 1964; filed at Lennox and Addington County Museum). Nick and Helma Mika, The Grand Junction Railway (Belleville, 1985). Nila Reynolds, Bancroft, a bonanza of memories ([Bancroft, Ont.], 1979). Merrill Denison, “The Hon. Billa Flint,” Canadian Mining Journal (Gardenvale, Que.), 88 (1967): 49–52. J. H. Richards, “Population and the economic base in northern Hastings County, Ontario,” Canadian Geographer (Ottawa), no11 (1958): 23–33.

Cite This Article

Larry Turner, “FLINT, BILLA,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 1, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/flint_billa_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/flint_billa_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Larry Turner |

| Title of Article: | FLINT, BILLA |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | April 1, 2025 |