Source: Link

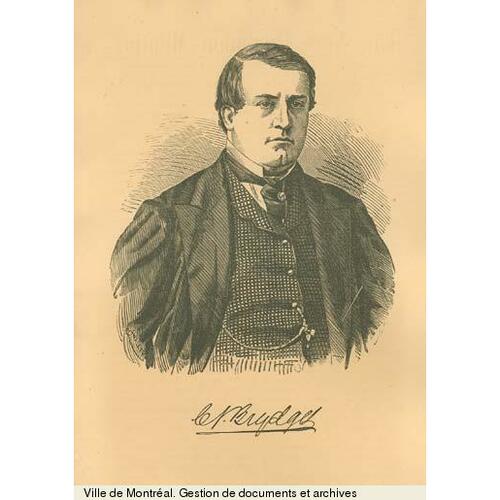

BRYDGES, CHARLES JOHN, railway official, civil servant, and HBC land commissioner; b. February 1827 in London, England; m. in 1849 Letitia Grace Henderson, and they had two sons and one daughter; d. 16 Feb. 1889 in Winnipeg, Man.

The names of Charles John Brydges’ parents are unknown, but during his successful middle years he claimed a connection with the barony of Chandos, then much in dispute. His father died before he was two and his mother five years later. With no siblings or close relatives, he entered boarding-school for nine years – dependent for his future upon only a small legacy, driving ambition, and an extraordinary capacity for work.

In 1843 Brydges was appointed a junior clerk in the London and South-Western Railway Company. During his ten years there he served a varied apprenticeship that helped to prepare him for his managerial career in Canada. Although not a trained scientist or engineer, he admired such contemporary British railway experts as Isambard Kingdom Brunel of the Great Western Railway; he was also attracted to schemes for the self-improvement and financial welfare of railway employees. As honorary secretary of the railway’s literary and scientific institution he provided leadership to an employees’ library, donated a collection of mechanical drawings, gave lectures for adult improvement, and supported a children’s school. Already appreciating personal connections, Brydges initiated a “friendly society” to benefit the railway’s workmen, and, knowing the need for financial prudence, he pressed on the company and its employees the urgency of contributory superannuation provisions. In 1852 he published these and other views in a pamphlet, Railway superannuation: an examination of the scheme of the General Railway Association for providing superannuation allowances to worn out and disabled railway employés. Brydges continually demonstrated his concern for employees’ welfare and self-respect; he often clashed with his managerial peers, but throughout his career he won respect and affection from the rank and file.

Brydges’ years with the London and South-Western culminated in his appointment as assistant secretary. He was not content, however, to await indefinitely the final promotion possible from within company ranks. In 1852 he was offered the post of managing director of the Great Western Rail Road Company of Canada. Notwithstanding a hasty offer of the secretaryship and efforts by the directors to obtain his release after he had accepted the overseas post, Brydges was off to Canada. Although only 26, he was determined to strike out afresh, putting his apprenticeship to the test in a promising managerial challenge.

Brydges’ new appointment illustrated the problems inherent in the development of huge ventures by colonial promoters who were heavily dependent upon external capital. With favourable provincial legislation and local supporters such as Sir Allan Napier MacNab*, as well as Peter* and Isaac Buchanan, earlier schemes for a southwest rail network in Canada West had finally been parlayed into the Great Western. The project depended upon private British investors for more than 90 per cent of its capitalization, however, and the Canadian board was shadowed by a London corresponding committee. Brydges was the committee’s appointee; this factor, combined with his youth, compromised his position. Yet, with characteristic energy and confidence, he soon played skilfully to both sides of the house.

Three characteristics marked Brydges’ performance at the Great Western. First, he operated comprehensively rather than concentrating on a few issues. He began by improving administrative efficiency and by reducing slipshod contracting and accounting; even legal matters received his careful attention. For two years he had only a single departmental superintendent (in traffic), responsibility for all other departments and their coordination falling directly upon himself. At the time of his arrival in Canada early in 1853, however, his most immediate challenge was construction.

Against the advice of his chief engineer, John T. Clarke, he rushed the poorly built line to technical completion as a running line within the year. He thus placated his Canadian board, stole a march on other Canadian railway projects in the region (notably the Grand Trunk), and could impress potential American through lines with the Great Western’s value as a Canadian “short cut” to the Midwest. The legacy of his precipitate action would be severe maintenance and financial problems, as well as an alarming accident rate. On balance, however, this calculated gamble was probably warranted if the line was to be recognized as a major operation with important American connections.

Brydges’ drive for consolidation was the second characteristic that shaped the development of the railway. Technically, this led to varied, sometimes doubtful projects such as the railway deck on the Niagara Gorge bridge, expensive car-ferry and ice-breaker facilities on the Detroit River, and the fruitless acquisition of steamers for the run from Hamilton, Canada West, to Oswego, N.Y. Territorial acquisition in the southwestern traffic area was, in contrast, vital. His British committee assumed that absorption of small lines, such as the London and Port Sarnia, must be unprofitable. However, Brydges, like the Canadians, recognized their tactical importance in forestalling Grand Trunk and American competition. Playing a dangerous game, with his loyalties divided between British and Canadian interests, he advised Peter Buchanan, the road’s sole agent in London, against “the sending out of two directors from England to sit at our Board.” His position on the board gave him great leverage over the inexperienced Canadian promoters and his distance from London was opportune. With sharp traffic increases and enthusiastic support from affected communities, Brydges’ confidence soon carried him too far.

Evidence of his headstrong ways was provided by his grandly optimistic prediction of profits. Brydges was still dangerously unfamiliar with road-bed and rolling-stock deterioration in Canada, and this inexperience supplemented the board’s indifference to heavy indebtedness. Consequently, their joint decision to repay government advances was unwise, politically unnecessary, and alarming to expectant British shareholders. Brydges’ attempt to lease the Buffalo and Lake Huron as well as to purchase the bankrupt Detroit and Milwaukee, combined with the financial panic of 1857, precipitated the establishment of an internal stockholders’ committee in Britain, headed by H. H. Carman, to inquire into the line’s management.

The investigation focused upon Brydges’ third quality, his authoritarianism. Even Peter Buchanan had earlier remarked upon his wilfulness: “Brydges requires a master over him and that party ought to be President with a couple of thousand a year and nothing else to do.” Although this view was held by many on both sides of the Atlantic by 1858, it was not entirely fair because Brydges’ authoritarianism was exacerbated by the weakness of his executive and the available personnel. Attempts had been made from 1854 by London to outflank him by creating more senior administrative posts. Divisions between the board and the corresponding committee together with inexperience and petulance among the English appointees only confirmed his indispensability. By attempting to lay all the faults of the line at his feet, the Cannan committee created a backlash in his favour. Brydges and the directors received a firm vote of confidence from the stockholders on 11 April 1861.

Accordingly, he turned with renewed confidence to an earlier project of “fusion” with the less aggressive Grand Trunk Railway. Anticipating this merger, in December 1861 he became the Grand Trunk’s superintendent while remaining managing director of the Great Western. Amalgamation might appeal to his wavering Canadian directors but it was still unacceptable to London, and to the Canadian legislature it smacked of unbridled monopoly (the lines did finally amalgamate in 1884). Rebuffed, still under suspicion in London for his apostasy, and resented by many Canadian colleagues for his wilfulness, Brydges reviewed his position. The directors of the Great Western had never recognized the Detroit and Milwaukee venture as a stage in the line’s progress to the west. The Grand Trunk was a company of grander scope and, as he had learned after the severing of MacNab’s connection with the Great Western, one with firmer political support. If politics and vision were necessary ingredients of successful Canadian railroading, he would move with the winners. Late in 1862, he resigned his post with the Great Western to become general manager of the Grand Trunk.

Brydges might have had to struggle with an undiminished and hopeless legacy of errors in Grand Trunk construction, maintenance, and operation. Fortunately, his predecessor as manager, soon to be president, was Edward William Watkin. Most of Brydges’ years with the Grand Trunk were spent in Watkin’s shadow, but because Watkin was his sort of comprehensive, consolidating manager Brydges was satisfied to be his hard-driving lieutenant. Rooting out inefficiency, seeking technical improvements, expanding capacity, and importuning government for larger postal and military subsidies, they made a strong team. Brydges also assisted by beginning a long career as a Tory counsellor, patronage agent, and self-appointed adviser to John A. Macdonald*. He courted Montreal business leaders; he engaged prominently, and with conviction and dedication, in civic affairs, especially poor relief and hospitals, and in Anglican causes. On the job he built up the employees’ morale and loyalty by supporting reading-rooms, education for workers, and improved benefits. As a lieutenant-colonel, with his popular older son as aide-de-camp, he organized the Grand Trunk Railway Regiment, on 27 April 1866, to meet the Fenian threat [see John O’Neill*]. The move further aroused the men’s loyalty – and recommended the railway to the government for its responsibility. Brydges also aided Watkin’s campaign for trunk expansion by helping to arrange the series of exchanges between Canadian and seaboard leaders which allowed the regional representatives to become acquainted with one another and assisted in preparing the way for confederation.

When Watkin was forced out in 1869, by circumstances and pressures not unlike those Brydges had experienced at the Great Western, the best days were over. The new president, Richard Potter, was never to show the same confidence in Brydges, nor could he as ably turn away shareholders’ criticisms. By 1872 Potter’s faith was shaken by two developments: his belief that if Brydges had not obtained kickbacks on rentals of rolling-stock he had at least set these rentals at exorbitant rates; and the realization that Brydges still could not delegate authority and was responsible for alarming administrative lapses by over-extending himself. Potter, like the Great Western committee, tried to force new senior colleagues on him, and Brydges’ resentment grew throughout 1873 and 1874.

Meantime, since 1868 he had represented Ontario and Quebec on the supervisory Board of Railway Commissioners, a federal body, with provincial representatives, which was established to superintend the construction of the Intercolonial Railway. Having gained unusual power because of the other commissioners’ inexperience, as he had on the Great Western board, he was preparing for a new career as government adviser on railway matters. His clashes with the Intercolonial’s presiding engineer, Sandford Fleming*, gave him increasing prominence and authority. His resignation from the Grand Trunk in March 1874 was therefore not a desperate decision.

Brydges’ break was further softened by two developments. First, he received severance pay of 4,000 guineas and a $10,000 bond from Quebec friends and especially from Grand Trunk employees. Secondly, in 1874, when the Board of Railway Commissioners was removed and the Intercolonial was placed under the direct control of the federal Department of Public Works, the new Liberal prime minister, Alexander Mackenzie*, chose Brydges to oversee the remaining construction of the road and appointed him general superintendent of government railways. Unswervingly honest, Mackenzie, by appointing a confidant of Macdonald and an allegedly dishonest manipulator, raised doubts about the charges against Brydges. Mackenzie’s obsessive moral concern should have prevailed even over his anxiety to get an experienced railway assistant. Although Brydges chafed at Mackenzie’s caution and piecemeal approach to the proposed Pacific railway, they worked together effectively for four years.

Simultaneously, however, Brydges alienated Maritimers of both parties. Following Mackenzie’s instructions he reduced the Intercolonial staff and costs by 25 per cent and appointed capable men of whatever party. Liberal patronage agents were outraged but Conservatives were also affected by Brydges’ attacks (Tory workers dismissed from the railway, Sandford Fleming, and especially Charles Tupper*, who was accused of receiving kickbacks connected with the Intercolonial). Maritimers were briefly united in demanding Brydges’ dismissal. In 1878, with Macdonald’s return to power and Tupper as minister of public works, only the timing of Brydges’ firing was at issue. It came in January 1879.

In that year, through his managerial reputation and continuing connections within the Tory party, Brydges began a new career in the Hudson’s Bay Company. Nominally land commissioner of the HBC, he was secretly authorized by the governor, the deputy governor (Sir John Rose), and the board of the company to follow the principle of consolidation in a new context. He should progressively take over all company operations, including land, furs, supplies, and stores, thus supplanting Donald Alexander Smith* and others and creating what was in effect a more varied and comprehensive chief commissionership. Ironically, Brydges’ company years coincided with Smith’s rise as liaison officer between Ottawa, the HBC, and the Canadian Pacific Railway, climaxed by Smith becoming the HBC’s largest shareholder and governor. As Brydges’ most exacting assignment, his connection with the HBC produced strains which would precipitate his death but it also held its triumphs.

His arrival in Winnipeg in May 1879 was like that of a great administrative juggernaut. Extensive surveys began in prospect of a “Manitoba fever”; new administrative, legal, accounting, and advertising machinery emerged; contracts for supplies to Indians and the North-West Mounted Police became competitive; new hotel and milling facilities enhanced the value of HBC lands; a subsidiary bridge company for the Red and Assiniboine rivers at Winnipeg was formed; the retail stores were reorganized under new men, not those only “accustomed to the barter system with the Indians”; supervision of barge and steam transport of goods and passengers was wrenched from the hands of “incompetents”; and, finally, executive operations were permanently moved from Montreal to Winnipeg in November 1880. Within a year the HBC was recognized as the most reliable source for information on settlement and commerce in Manitoba and the North-West Territories.

Brydges held that the HBC should erase the image of the old fur-trading company which was speculative and passive in its social and regional concerns – intent on incremental profits from the industry of others. It should instead identify with the northwest, even at the risk of offending vested political and economic interests. This boldness would eventually prove his undoing.

Brydges himself assumed a leading role in the rapidly expanding town of Winnipeg. As in Montreal he was prominent in civic activities: energetic chairman of the general hospital, president of the board of trade and of the Manitoba Board of Agriculture, an outstanding diocesan figure, and a determined advocate of retrenchment in municipal proliferation and taxation throughout Manitoba. Although a supporter of the property owners’ association, he acted independently of the “Citizen’s Ticket” urban reform movement – perhaps because it was dominated by CPR figures. He was determined to make the HBC a part of the growing regional consciousness in Manitoba and the west.

His forthrightness exasperated many people and he could not escape charges of partisanship. He was a major investor in Alexander Tilloch Galt*’s North-Western Coal and Navigation Company, formed to develop coal deposits on the Belly and Bow rivers (Alta), and this involvement alarmed the CPR, particularly in view of the old Grand Trunk connections of Galt and Brydges. Advocating Winnipeg over Selkirk for the CPR crossing of the Red River earned him the gratitude of Bishop Alexandre-Antonin Taché* and the Winnipeg business interests, but further alienated Sandford Fleming and the CPR hierarchy, and eroded Brydges’ good relations with Ottawa. Although pressured to establish policies for the promotion of immigration as well as for the development and sale of land jointly with the CPR, he demurred, for he foresaw inherent complications and competition. He felt that the HBC should remain free to criticize the CPR’s monopolistic rates and branch lines policies, thereby lining up with western interests. Inevitably, these tactics alarmed CPR supporters such as George Stephen*, Donald Smith, and perhaps even Sir John A. Macdonald. This was Brydges’ dilemma. Even Smith’s rising power in the HBC did not deter Brydges from joining the Winnipeg Board of Trade and the Manitoba Board of Agriculture in condemning the CPR’s branch lines monopoly. The suspicions of the railway and the government were exacerbated by unfounded rumours that he was helping the Grand Trunk undermine the CPR’s bond sales prospects by feeding information critical of the CPR to agents of the Grand Trunk who used it on the money markets in New York and London.

To retaliate, in 1882 Smith forced a review by the HBC of Brydges’ land administration, and the investigating committee included his old rival, Sandford Fleming. Brydges was mildly reproved for laxity when the committee discovered extensive speculation by several of his associates but he was himself cleared and granted a generous purse for his competence and forbearance. Nevertheless, Smith won the last round. For more than two years, beginning in May 1884, Brydges was saddled with a supervisory “Canadian Sub-Committee,” consisting of Smith and Fleming, which was largely ineffectual and which only hamstrung him in meeting the severe challenges of the Manitoba “bust” following the massive speculation connected with the arrival of the CPR.

Brydges’ success in recovering company land and maintaining payments between 1882 and 1889 was perhaps his finest managerial achievement. By carefully pressing for payments when economic conditions improved and relaxing demands during hard times he countered the effects of the crash, and retained many original settlers on company lands. The HBC would realize nearly $900,000 in collections and recoveries of unpaid early instalments, while retaining its reputation for efficiency and fair dealing. Brydges obviously expected warm commendation for his efforts. Instead, he soon faced Smith’s most effective attack yet.

Although Brydges had sharply criticized the CPR, he had always preferred the Canadian syndicate to American railway incursions into Manitoba. By 1888, however, he so sympathized with Manitoba’s battles with Ottawa over disallowance of provincial branch lines [see John Norquay] that his headstrong actions plunged him into a new crisis. Miscalculating Smith’s strength on the HBC board, he pushed the directors to grant an American line, the Northern Pacific Railroad, access to company land in Winnipeg to provide competition for the CPR and improve HBC property in the centre of the city. Rebuffed by the board, Brydges entered a period of great defensiveness and agitation, which precipitated his sudden collapse and death from a heart attack on 16 Feb. 1889. He died on Saturday afternoon when, characteristically, as founding chairman he was making his weekly inspection of the Winnipeg General Hospital.

Brydges was never as significant in Canadian public life as he liked to assume. However, his association with large enterprises and his aggressive, usually efficient ways brought him considerable prominence. His early managerial positions in central Canadian railways had provoked much controversy and his career as a watchdog over government railways had made him the object of bitter partisanship. During his years in the west his deserved reputation for enterprise continued and his attempts to deal fairly with the settlers and to align the interest of his employers more closely with local needs enhanced that reputation. On balance, he had discharged his duties forthrightly and responsibly. Representing a middle level of public and private entrepreneurship in Canada, Brydges was too abrasive to be totally effective, yet strong enough to gain respect from a later generation, removed from the particular forms of intolerance and suspicion through which he had lived.

Charles John Brydges was the author of Grand Trunk Railway of Canada; letter from Mr. Brydges in regard to trade between Canada and the lower provinces (Montreal, 1866); Great Western Railway of Canada; Mr. Brydges’ reply to the pamphlet published by Mr. H. B. Willson (Hamilton, [Ont.], 1860); Hudson’s Bay Company (Land Department): report . . . (London, 1882); Mr. Potter’s letter on Canadian railways, reviewed, in an official communication addressed to the Hon. Alexander Mackenzie, premier of the dominion (Ottawa, 1875); and Railway superannuation: an examination of the scheme of the General Railway Association for providing superannuation allowances to worn out and disabled railway employés (London, 1852). His letters as land commissioner, in PAM, HBCA, A.12/18–26, have been published in The letters of Charles John Brydges, 1879–1882, Hudson’s Bay Company land commissioner, ed. Hartwell Bowsfield with an intro. by Alan Wilson (Winnipeg, 1977).

AO, MU 1143; MU 2664–776. N.B. Museum, Tilley family papers. PAC, MG 24, D16; D79; MG 26, A; B; F; MG 29, B1; B6; RG 30. Sandford Fleming, The Intercolonial: a historical sketch of the inception, location, construction and completion of the line of railway uniting the inland and Atlantic provinces of the dominion . . . (Montreal and London, 1876). Notman and Taylor, Portraits of British Americans, I. P. A. Baskerville, “The boardroom and beyond; aspects of the Upper Canadian community” (phd thesis, Queen’s Univ., Kingston, Ont., 1973). Currie, Grand Trunk Railway. Douglas McCalla, “Peter Buchanan, London agent for the Great Western Railway of Canada,” Canadian business history; selected studies, 1497–1971, ed. D. S. Macmillan (Toronto, 1972), 197–216. G. R. Stevens, Canadian National Railways (2v., Toronto and Vancouver, 1960–62), I. Alan Wilson, “Fleming and Tupper: the fall of the Siamese twins, 1880,” Character and circumstance: essays in honour of Donald Grant Creighton, ed. J. S. Moir (Toronto, 1970), 99–127; “‘In a business way’: C. J. Brydges and the Hudson’s Bay Company, 1879–89,” The west and the nation: essays in honour of W. L. Morton, ed. Carl Berger and Ramsay Cook (Toronto, 1976), 114–39.

Cite This Article

Alan Wilson and R. A. Hotchkiss, “BRYDGES, CHARLES JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 4, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brydges_charles_john_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brydges_charles_john_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Alan Wilson and R. A. Hotchkiss |

| Title of Article: | BRYDGES, CHARLES JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | April 4, 2025 |