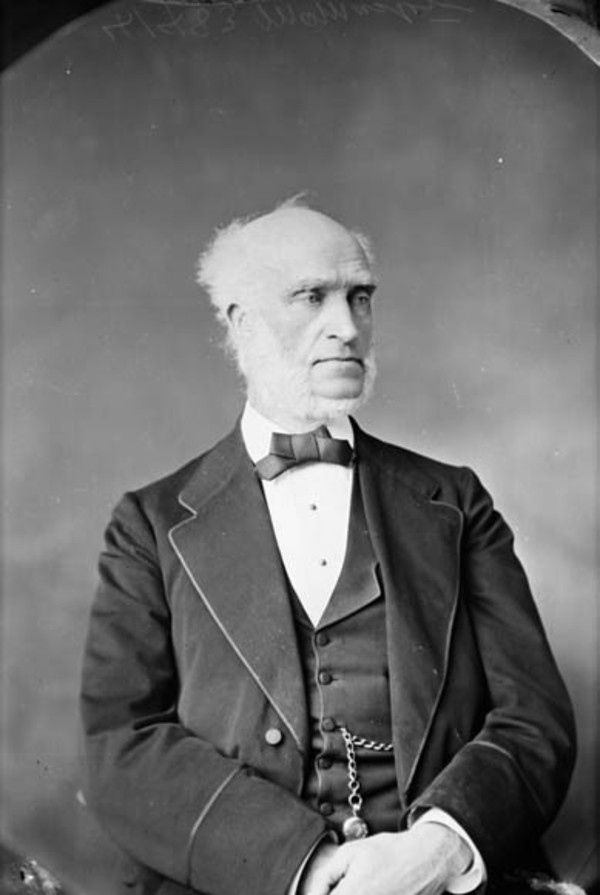

McMASTER, WILLIAM, businessman, politician, banker, and philanthropist; b. 24 Dec. 1811 in County Tyrone (Northern Ireland), son of William McMaster, a linen-draper; d. 22 Sept. 1887 in Toronto, Ont.

William McMaster was educated privately by a well-regarded local teacher, and when about ten he was converted and apparently joined the Baptist church in Omagh. After he had gained some experience as a clerk in an Irish mercantile house, he came to North America and, following a brief stay in New York City, moved to York (Toronto), Upper Canada, in August 1833. The popular version of McMaster’s immigration holds that he arrived in York without friends or money, found employment as a clerk in Robert Cathcart’s wholesale and retail dry goods firm, and owed his success to merit alone. Another account states that Cathcart, who had established his business in 1828 or 1829, later brought out his nephews from Ireland, one of whom was William McMaster. Both versions agree that McMaster rapidly became an asset to his employer. Within a year or two of his arrival he was a partner in the firm. In July 1844, when Cathcart retired, he took over the business.

McMaster’s further success owed much to his skill in recognizing opportunities and to his ability to move in time with important commercial trends. Decisions he made in 1844, to concentrate on wholesale dry goods and to move his company to Yonge Street, were shrewd ones. The dry goods trade, located at the southern end of Yonge Street, would prove to be one of Toronto’s most profitable lines. An enterprise such as McMaster’s fulfilled the requirements of a population clamouring for imported goods. In 1850 the business cleared $10,000, but apparently did not as yet rank among the largest general wholesalers in Toronto. The agents of R. G. Dun and Company reported McMaster’s wealth to be in the $300,000–$400,000 range in 1853 and in the $600,000–$800,000 range in 1859. McMaster resisted the temptation to expand beyond his financial resources and his caution enabled him to emerge from the recession of 1857 with his business intact. Early in his career he had been described by Dun’s agent as “probably the safest man in business in Toronto” and later reports repeated that his judgement could be relied upon for any credit he requested. By 1860, when the dry goods wholesalers had emerged as the wealthiest merchants in the city, McMaster’s company was considered by R. G. Dun to be “the largest Dry Goods Concern in Western Canada.”

Having no children, McMaster had taken two of his nephews from Ireland, Arthur Robinson McMaster and James Short McMaster, into the business as bookkeeper and English buyer respectively. They became his partners in the firm William McMaster and Nephews on 1 March 1859 and J. S. McMaster took up residence in Manchester to oversee the English interests of the company. Contemporaries described the family as “close people, their affairs known only to themselves.”

William McMaster entered politics in 1862 when he was elected as a Liberal to represent the Midland division in the Legislative Council. His sympathies lay with men such as George Brown* and other Reformers concerned with the commercial expansion of Toronto and Canada West. He was drawn as well by their interest in measures to improve the position of evangelical Nonconformists, including his own Baptist co-religionists. In the spring of 1867 he served on the central executive committee of the newly revived Reform Association of Upper Canada and became a director of its Toronto branch. He received an appointment to the first dominion Senate and remained a member for the rest of his life. When he spoke in Senate debates, his comments were succinct and usually related to subjects that concerned him personally: banking and finance, bills affecting companies with which he was associated, and matters touching him as a Baptist.

By the early 1860s William McMaster and Nephews, originally an “active, pushing” business, had come to be regarded as an old firm dealing with an established clientele. This change may well have led McMaster, who had spoken of retiring as early as 1859, to expand his commercial interests. He relinquished the management of the company in 1863, though retaining a large financial interest, reputedly $400,000, and the firm became known as A. R. McMaster and Brother. In the process of building up his business William McMaster had contributed markedly to Toronto’s metropolitan development and to its attempt to wrest control of the central Canadian economy from Montreal. He was an active member of the Toronto Board of Trade, having been on its council eight times by 1861, after which he left the representation of the McMaster interest to other members of the family. During the late 1850s and the 1860s he was also a director of the Ontario Bank, the Wellington, Grey and Bruce Railway, the Canada Landed Credit Company, and the Toronto and Georgian Bay Canal Company (after 1865 the Huron and Ontario Ship Canal Company). He was a member of the first board of directors of the North-West Transportation, Navigation and Railway Company in 1858, which hoped to establish direct communication between Toronto and Rupert’s Land so that the raw materials of the northwest might be exploited and its potential as a market tapped [see Allan Macdonell].

The rivalry between Montreal and Toronto also played an important part in McMaster’s decision to pursue a banking career in the 1860s. Even though he accepted an appointment as a Toronto director of the Bank of Montreal in 1864, McMaster was distressed by the ascendancy of the bank in Canada West. Under the leadership of its general manager, Edwin Henry King*, the bank was restricting the amount of credit available in Canada West by withdrawing capital to accommodate a constantly increasing business with the provincial government; in January 1864 the government transferred its account to the bank [see Robert Cassels]. Two years later, the Bank of Montreal was the only bank to take advantage of new legislation enabling banks to surrender their notes in favour of those issued by the government; it thus became the sole agent for issuing the government notes. In the uncertain days which preceded the failure of the Bank of Upper Canada in 1866 and the Commercial Bank of Canada in 1867, McMaster and the Toronto business community moved to arrest the growing control of the Bank of Montreal in Canada West. McMaster and Archibald Greer, the Toronto manager for the Bank of Montreal, after remonstrating in vain with the bank against these policies of credit restriction, withdrew from it to establish a bank designed to meet the credit needs created by King’s actions. The charter of the Bank of Canada, which had been inactive since 1858, was purchased from William Cayley and others, and in August 1866 amendments to this charter were obtained which changed the name to the Canadian Bank of Commerce and revised the required capital stock from $3,000,000 to $1,000,000. Unlike many of the banks proposed during the period, the Canadian Bank of Commerce had little difficulty in filling its initial subscription of shares. McMaster had brought to the new bank both the support of the Toronto business community and his own reputation as a shrewd businessman with private dealings on the New York and London money markets. His agents, Caldwell Ashworth in New York and J. S. McMaster, who moved his office to London’s financial district, took on the international business of the bank.

On 18 April 1867 the shareholders of the bank had their first meeting. McMaster, who held 500 shares valued at $25,000, was elected president and Henry Stark Howland* vice-president. The directorate, drawn from the ranks of prominent Toronto businessmen and financiers, included such men as John Taylor* and John Macdonald (who resigned within three weeks and was replaced by James Austin*). In June 1869 the bank increased its authorized capital stock to $2,000,000 and the following year parliament approved an increase to $4,000,000, as a result of the amalgamation with the Gore Bank. When in 1871 the directors increased the authorized capital to $6,000,000, matching that of the Bank of Montreal and the Merchants’ Bank of Canada, the Monetary Times noted that theirs was a “bold, not to say ambitious policy.” The amount was paid by 1874. Not all the directors shared McMaster’s desire for growth at the expense of short-term profit. Austin left the board in 1870 and Howland resigned in 1874; both went to newer banks where a higher return might be expected from less capital.

McMaster had launched the Canadian Bank of Commerce amid great uncertainty about the future of Canadian banking. New legislation proposed in 1868 and introduced the following year by the federal minister of finance, John Rose, was drawn up in consultation with King of the Bank of Montreal. The ability of chartered banks to issue notes of their own, the quantity of government securities which they might be required to hold, and the continuation of the existing system of branch banking were at stake. Under Rose’s legislation Canadian banks would all have had to purchase government notes from the Bank of Montreal. Protests against Rose’s proposals came from across the country but McMaster avoided leading the opposition of Ontario banks, leaving this role to George Hague, cashier (general manager) of the Bank of Toronto. He also refused to chair the Senate committee on banking, commerce, and railways when the position was offered to him by Rose in April 1869. Although he declined in the fear that opposition by him to the legislation would endanger the bills he had before the house concerning the Canadian Bank of Commerce, he also felt that the banking community should use its influence to amend legislation that might seem to be inevitable rather than risk hardening the attitude of the government by open opposition. In the event, the government chose to withdraw the contentious legislation and Rose resigned.

The appointment of Francis Hincks as minister of finance on 9 Oct. 1869 relieved McMaster of his awkward position. Hincks was sympathetic to the Ontario lobby and McMaster felt that he could accept Hincks’s offer of the chairmanship of the Senate committee in 1870. McMaster gave Hincks steady support even in the face of opposition from his fellow Liberals, opposition he dismissed as opportunistic. He immersed himself in committee work which, despite weary moments, he seems to have enjoyed thoroughly, and he worked with Hincks to render the latter’s banking legislation “as perfect as possible.” In the end, the acts of 1870 and 1871 gave McMaster and other Ontario bankers the conditions they wanted to develop their institutions within the province.

By 1872 the Canadian Bank of Commerce had established a “large healthy business” and had built up a reserve fund of $1,000,000. In addition, it had absorbed the initial costs of opening new branches: 19 in Ontario, one in Montreal, and one in New York to facilitate “transactions in exchange.” Two years later when the province slipped into a recession the growth of the bank slackened but McMaster and his fellow directors met the situation with confidence. They adopted a conservative policy aiming temporarily for “safety rather than large profits.” The bank perhaps fared worse in the recession of 1882 because its management was growing old and less vigilant in assessing accounts. In the mid 1880s the liquidation of several large estates held by the bank revealed that their assets had been greatly overvalued. A historian of the bank describes the years 1884–87 as “possibly the most difficult” in its history.

In July 1886 McMaster stepped down as president of the Canadian Bank of Commerce at its annual meeting, citing as reasons his poor health and the need for new men. He remained a director, however, and proposed his successor, Henry W. Darling; a major reorganization of senior positions followed his resignation. By 1887 the bank had surpassed the Merchants’ Bank of Canada in size and was now second only to the Bank of Montreal. McMaster’s decision to place it in the first rank of competition among Canadian banks, a decision which had been contested by some members of his original board, was accepted by his successors as the determining factor in the policies they followed.

His success in business and finance attracted numerous directorships for McMaster. He was chairman of the Canadian board of directors of the Great Western Railway from at least 1867 until it was disbanded in 1874, and in the following year he was the only Canadian appointed to the English board when shareholders, disgruntled with the way in which the line had been operated in Canada, decided to reorganize the railway; he continued as a director of the English board until the railway was taken over by the Grand Trunk in 1882. He served the railway well in its financial negotiations with the Canadian government, in particular with regard to the arrangements made in 1869 for repayment of its government loans. McMaster was also president of the Freehold Loan and Savings Company, which under his direction became closely integrated with the Canadian Bank of Commerce, and he was 1st vice-president of the Confederation Life Association from its incorporation in 1871 until his death in 1887. He helped steer the association, with assets of over $100,000 in 1872, to its position as the second largest Canadian-based life insurance company in 1885. McMaster was one of the original directors of the Isolated Risk Fire Insurance Company (after 1873 the Isolated Risk and Farmers’ Fire Insurance Company). He served for some time as a director of the London and Canadian Loan and Agency Company and of the Toronto General Trusts Company, a relatively new form of investment.

The triumphs McMaster engineered in business and finance were augmented by the work he undertook on behalf of the educational and religious needs of the Baptist constituency of central Canada. His contributions were influenced to some extent by the Reverend Robert Alexander Fyfe* of whose March Street Baptist Church (later Bond Street, and then Jarvis Street Baptist Church) McMaster was a member. As Daniel Edmund Thomson, a fellow Baptist and prominent Toronto lawyer, observed, McMaster was convinced that the Baptists were “a people of destiny” and he remained in that denomination even though his “business and social welfare would have been greatly promoted by his union with one of the larger and stronger bodies.” There were, to be sure, some observers who wondered whether McMaster’s reputed “love of aggrandizement” had too often choked his penchant for denominational philanthropy. Thomson pointed out on another occasion that the senator was “not naturally a generous man” and “graduated late as a philanthropist.” Even when McMaster did earmark funds for charitable purposes his motives were sometimes questioned. Those few of his associates who had tried in vain to check the relentless expansion of McMaster’s business might have sympathized with William Davies*, a Toronto meat-packer and fellow Baptist. Davies complained about the “hateful” spirit of “centralization” that had supposedly characterized McMaster’s sizeable underwriting of the city’s prestigious Jarvis Street Baptist Church in 1875.

Unquestionably McMaster placed a high premium on education. The senator generously aided the Toronto Mechanics’ Institute. He served on the senate of the University of Toronto after 1873 and represented Baptist interests on the Council of Public Instruction from 1865 to 1875, roles which earned him commendations from Egerton Ryerson, superintendent of education. In addition, he served for many years as treasurer of the Upper Canada Bible Society, a non-sectarian organization.

It was in the professional and ministerial training of Baptists that McMaster was most actively involved. At one time he apparently had an affiliation with the Disciples of Christ but had given it up because they discountenanced an educated clergy. The pioneering Canada Baptist College in Montreal had been forced to close in 1849, and there is evidence that McMaster agreed to fund a successor, the proposed Maclay college. When this project failed, he assisted Fyfe in establishing a more substantial successor in Woodstock, Canada West. The Canadian Literary Institute (renamed Woodstock College in 1883), which opened in 1860, was designed as a co-educational facility offering instruction in arts and theology. When an opportunity presented itself in the late 1870s to move the institute’s theological department from Woodstock to Toronto, McMaster was eager to seize it. His decision was inspired in part by his second wife, Susan Fraser, née Moulton, the widow of an American businessman, whom he had married in 1871, three years after the death of his first wife, Mary Henderson. Susan Moulton Fraser had long been impressed with the work of the Northern Baptist Convention in the United States and was anxious to see the Baptist constituency in Canada emulate its educational facilities. An even more important role in persuading McMaster to help was played by Mrs McMaster’s American pastor, the Reverend John Harvard Castle, whom she had been instrumental in having called to the pulpit of Bond Street Baptist Church.

A special educational convention of Baptists in 1879 authorized the transfer of the theology department to Toronto and within a year McMaster had provided not only a site for it on Bloor Street but also an initial outlay of $100,000 and the pledge of an annual contribution of approximately $14,000. Although he was apparently reluctant to have his name associated with the building, his wishes were overborne in the naming of McMaster Hall. He insisted, however, on the school being known as a college rather than by the American term seminary. His British background and the hope that some arts subjects might ultimately supplement the theological curriculum may account for his insistence in this matter and explain why the school took the name Toronto Baptist College before it opened its doors to students in the fall of 1881.

For a time there was every prospect that this new denominational enterprise would federate with the University of Toronto, a relationship that many Baptists had encouraged in the belief that theological training should be the responsibility of each denomination and that a provincial university should instruct in the secular sphere. McMaster and others, however, eventually accepted the concept of an independent Baptist institution offering both theology and a more liberal and comprehensive arts programme at the collegiate level than was promised by the federation proposals of 1884–85. The leaders in this campaign for a separate institution included Castle, president of Toronto Baptist College, and two of his academic colleagues, Malcolm MacVicar, a confidant of the senator’s, and Theodore Harding Rand*, a prominent Maritime educator. It is possible that the senator’s wife may have urged him to endorse this campaign; there is an even better possibility that McMaster had toyed with the idea independently.

The plans for the new institution were approved by the Baptist conventions and a bill was introduced in the Ontario Legislature in March 1887 providing for the union of Woodstock College and Toronto Baptist College under the name of McMaster University. The senator appeared before the legislature on its behalf. Even before the bill was assented to on 23 April, he had made out, on 7 April, a will leaving the bulk of his estate, some $900,000, as an endowment for the new university. Barely five months later, on 22 Sept. 1887, he was taken ill while attending a meeting about its affairs, and died later the same day. He was survived by his widow, a sister, and nephews. After her husband’s death Susan Moulton McMaster donated the family’s Bloor Street mansion to the university. It became Moulton College, a school for girls.

Throughout the proceedings of building up Woodstock College to university status, McMaster had apparently privately favoured Toronto, the home of the Baptist college, as the site. The university did indeed find its location in 1888 at McMaster Hall, Toronto; in 1930 it moved to Hamilton. Its subsequent growth into an important Canadian educational institution gives a special significance to McMaster’s philanthropy, an activity he came to late in life after having achieved prominence as an influential banker and businessman.

We are grateful for the assistance of Charles M. Johnston and Wendy Cameron in the preparation of this biography.

Baker Library, R. G. Dun & Co. credit ledger, Canada, 26: 24, 183, 218, 237, 276; 27: 215, 294. Canadian Baptist Arch., Biog. files, J. H. Castle, William McMaster, Malcolm MacVicar, T. H. Rand; W. P. Cohoe, “The struggle for a sheepskin”; McMaster Univ., General corr., 1951–52 (H), 1957–59 (T); G. P. Gilmour corr., personal, 1962; Toronto Baptist College, Board of Trustees, Minute book, 12 April 1881–28 April 1887; Letters, 1880–86. Can., Senate, Debates, 1867–84. The Canadian Bank of Commerce: charter and annual reports, 1867–1907 (2v., Toronto, 1907), I. [William Davies], Letters of William Davies, Toronto, 1854–61, ed. W. S. Fox (Toronto, 1945). Toronto Board of Trade, Annual report . . . (Toronto), 1860–63; Annual review of the commerce of Toronto . . . , comp. W. S. Taylor (Toronto), 1867. Globe, 13, 16 Jan., 8 May 1860; 23 Sept. 1887. Toronto Daily Mail, 23, 26 Sept. 1887. The Baptist year book . . . (Toronto), 1882–86, especially the annual reports of the president of the Toronto Baptist College. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose, 1888), 286–89. Dent, Canadian portrait gallery, III: 72–74. Toronto directory, 1834–85. Careless, Brown. Currie, Grand Trunk Railway. Denison, Canada’s first bank. Robert Hamilton, “The founding of McMaster University” (bd thesis, McMaster Univ., Hamilton, Ont., 1938). Hist. of Toronto and county of York, II: 102–4. C. M. Johnston, McMaster University (2v., Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1976–81). Douglas McCalla, “The Toronto wholesale trade in the 1850’s: a study of commercial attitudes and practices” (unpublished paper, 1965). McMaster University, 1890–1940 . . . (Hamilton, 1940). Masters, Rise of Toronto. V. Ross and Trigge, Hist. of Canadian Bank of Commerce, II. C. B. Sissons, Egerton Ryerson, his life and letters (2v., Toronto and London, 1937–47). R. L. Kellock, “The Hon. William McMaster,” Canadian Baptist (Midland, Ont.), 90 (1944), no.8: 1, 4. D. C. Masters, “Canadian bankers of the last century, I: William McMaster,” Canadian Banker, 49 (1942): 389–96. D. E. Thomson, “William McMaster,” McMaster Univ. Monthly (Toronto), 1 (1891–92): 97–103.

Cite This Article

In collaboration, “McMASTER, WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 23, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcmaster_william_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcmaster_william_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | In collaboration |

| Title of Article: | McMASTER, WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | January 23, 2025 |