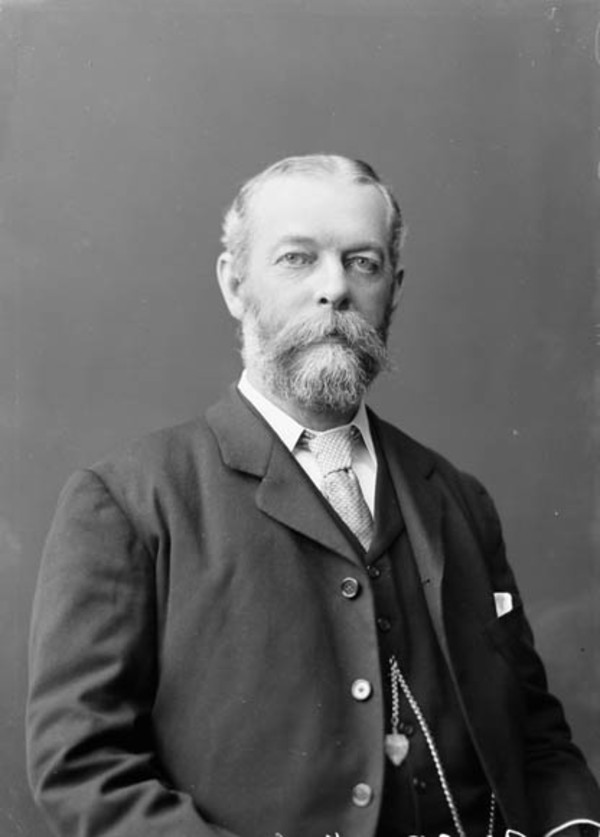

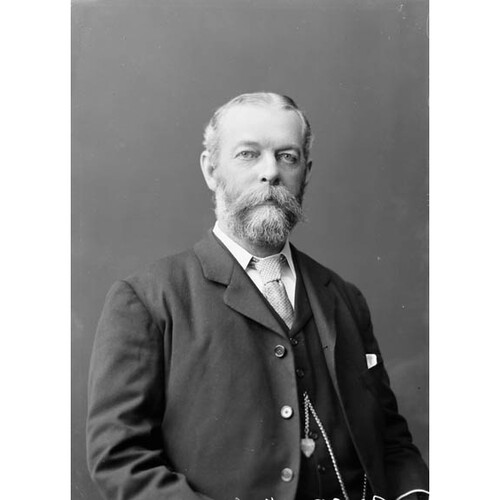

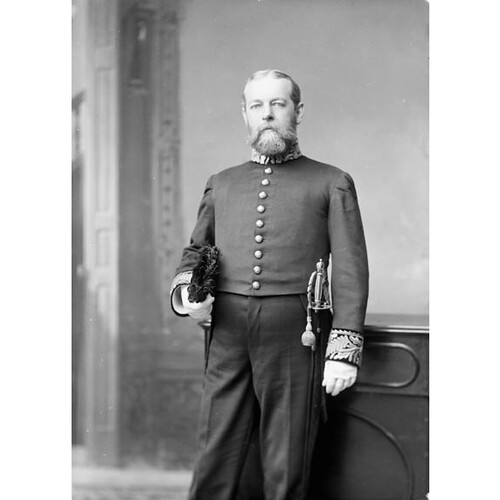

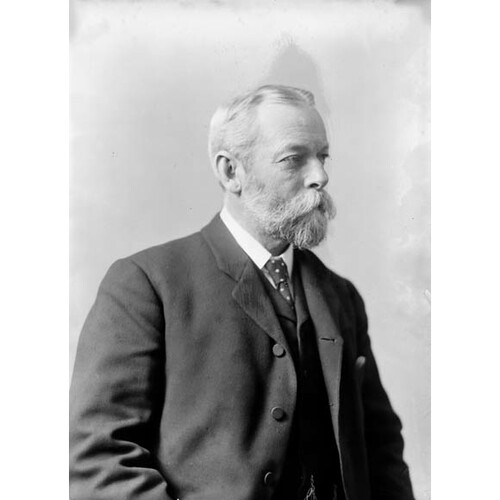

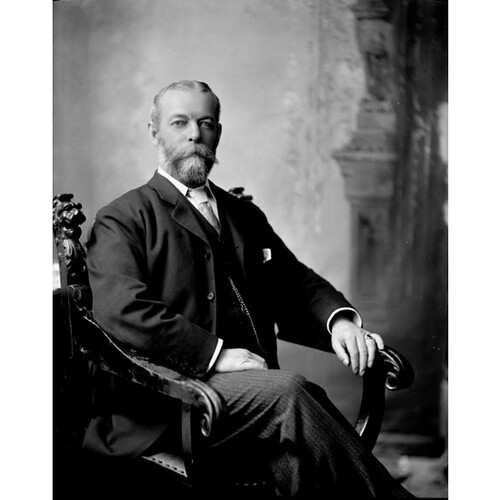

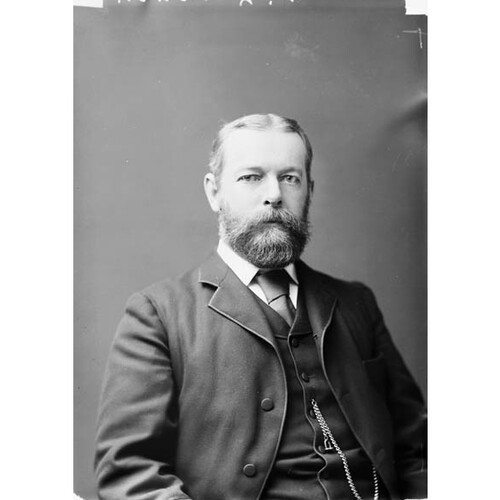

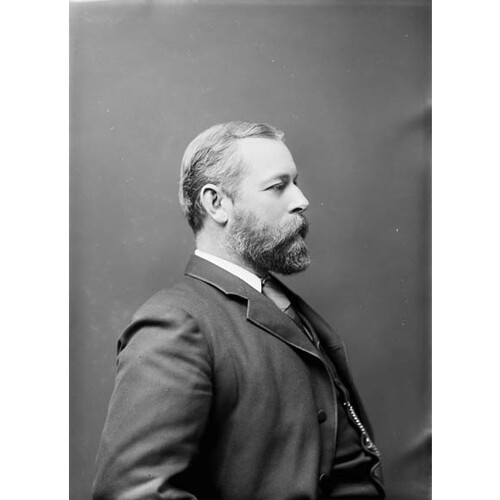

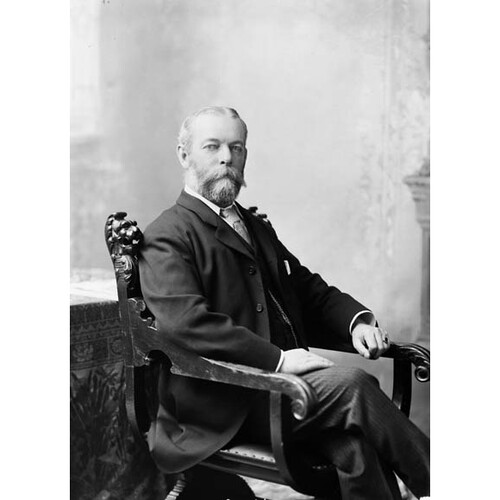

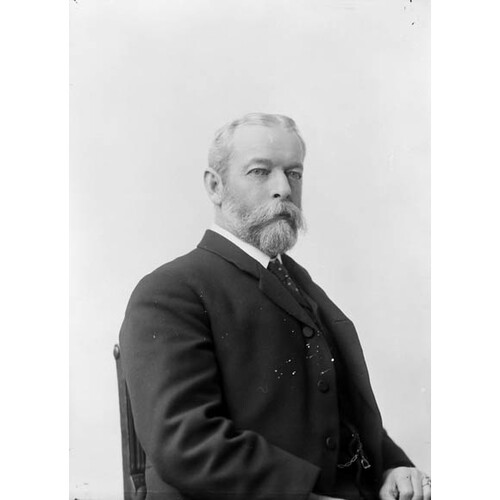

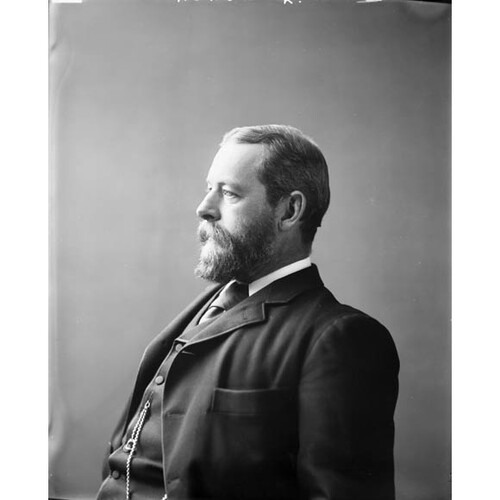

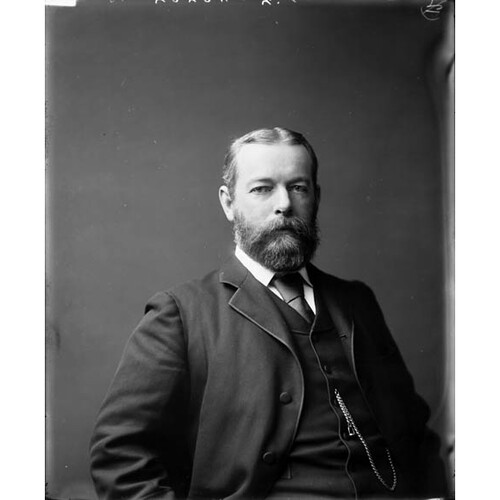

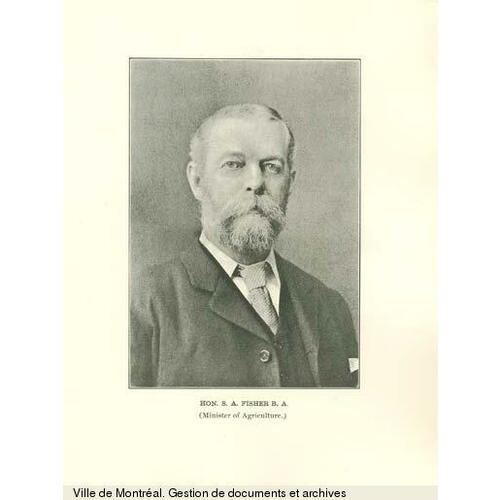

FISHER, SYDNEY ARTHUR, farmer, politician, office holder, and philanthropist; b. 12 June 1850 in Montreal, son of Arthur Fisher and Susan Corse; d. unmarried 10 April 1921 in Ottawa.

Originally from Scotland, Sydney Fisher’s paternal great-grandfather, Duncan Fisher*, immigrated to Montreal about 1777 and became a prominent citizen. Sydney’s father, who was educated in Montreal and at the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, became Montreal’s first practitioner of homoeopathy in 1842. Sydney’s mother was wealthy and the family travelled in Europe for extended periods. Educated at the High School of Montreal, Fisher graduated the top pupil of his class in 1866 and was awarded the Davidson Medal. He attended McGill College during 1866-68 and obtained a ba in political economy and scientific agriculture from Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1871.

In 1874 and 1875, with capital made available to him from his mother’s real estate holdings, Fisher purchased several lots in Brome Township, near the village of Knowlton (Lac-Brome). One of the properties belonged to judge Christopher Dunkin*, a friend of his father and an important farmer in the region. Fisher would develop his holdings, which he named Alva Farm, into a showplace of scientific agriculture. During the 1880s he made many contacts through his involvement in agricultural associations, including the Montreal Ensilage and Stock Feeding Association, the Brome County Agricultural Society, the Dairymen’s Association of the Province of Quebec, the Fruit Growers’ Association of the Province of Quebec, and the Canadian National Live-Stock Association. In 1884, at a meeting in Montreal of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, he delivered an address entitled “Agriculture in the province of Quebec.”

A Liberal, Fisher had failed in his first and only attempt to enter provincial politics, losing a by-election in Brome in November 1879. He was also unsuccessful in his first bid to enter federal politics, at a by-election held in Brome the following October. He obtained a narrow victory in the federal general election of June 1882. A free trader, he spoke in the commons in 1883 against the protectionism of Sir John A. Macdonald*’s government. He viewed increased tariffs on agricultural implements as harmful to farmers and those on materials used for tool manufacture as unhelpful to business. Although his elegant manners and bearing projected the image of a gentleman farmer, he would serve agriculture and politics equally well.

While sitting in the opposition, Fisher developed a close association with Wilfrid Laurier*, the Quebec leader and from 1887 the national leader of the Liberal party. In his extensive correspondence with Laurier, he revealed his belief that English and French Canadians should keep to their separate spheres. He was alarmed at the political climate after the execution of Métis leader Louis Riel* in 1885 and worried by Laurier’s suggestion that he be replaced in Brome by a French Canadian candidate in the federal election of 1887. Laurier consequently did some campaigning in the region without Fisher, who nonetheless retained his seat with a majority of 379 votes. During his second term he frequently addressed the commons on matters concerning agriculture, tariffs, or his constituency.

In the federal general election of March 1891 Fisher lost Brome by three votes. He was immediately appointed a justice of the peace. Out of office, he spent his time improving Alva and working for the Liberal party and various agricultural associations. In 1894 he accompanied Laurier during a visit to western Canada. The following year he organized a Liberal rally in Montreal and political meetings elsewhere in Quebec. In the federal election of 1896 he won Brome by over 330 votes.

On 13 July 1896 Fisher was sworn in as minister of agriculture in Laurier’s government. A well-educated and experienced politician of independent means, he had excellent qualifications for the post and had demonstrated that he was Laurier’s English-Canadian organizer in Quebec. After entering cabinet, he bought a house in Ottawa and was entertained as a sought-after bachelor, in demand at Mme Laurier’s dinner parties. During frequent visits to Montreal he stayed with his parents and he wrote to them or his aunt every day he was absent.

An advocate of temperance in a pro-temperance riding, Fisher had become a vice-president of the Dominion Alliance for the Total Suppression of the Liquor Traffic around 1882; he would hold the post for more than 15 years. At the Liberal party’s national convention of 1893 he prepared and presented the resolution in favour of a national plebiscite on the prohibition of alcohol. After the Liberals assumed office, Fisher introduced the legislation into the commons in 1898 [see Francis Stephens Spence*]. Although prohibitionists cast the majority of votes, Laurier avoided implementing the measure by pointing to the low overall voter turnout.

As minister for 15 years, Fisher accomplished much for Canadian agriculture. One of his first tasks had been to consult in December 1896 with Julius Sterling Morton, the American secretary of agriculture. Their departments agreed to cooperate in the tracking and reporting of disease in farm animals. The joint system of inspection led to increased livestock trade between the two countries. In the work of his department Fisher relied on the team of experts assembled in Ottawa. Chief among them were William Saunders*, director of the experimental farms system, James Wilson Robertson, dominion commissioner of agriculture and dairying, and James Fletcher*, dominion entomologist. Later, Fletcher’s successor, Charles Gordon Hewitt*, botanist Charles Edward Saunders*, and others would distinguish themselves. The work of these specialists led directly to measures such as the control of animal disease, plant disease and pests (the San José Scale Act, 1898, and the Destructive Insect and Pest Act, 1910), and seed purity (the Seed Control Act, 1905), as well as to the school garden movement. Under Fisher, a major expansion of the experimental farms system took place and new branches were created in the department, such as those for seeds, fruits, tobacco, and foreign exhibitions.

During his first term as minister, Fisher had revolutionized the marketing and transportation of Canadian produce, especially dairy products and fruit. Legislation in 1897 and 1898 provided for government subsidies to, and inspection of, cold storage warehouses in major eastern centres and refrigeration facilities on steamships leaving eastern ports for Great Britain and the West Indies. The Canadian Pacific Railway supplied cold storage from 31 points to Montreal. Other improvements followed in order to guarantee the quality of agricultural products. Over 900 cheese factories and creameries were obliged to register with the department and to date accurately their cheese and butter products for export. Fisher later legislated against the sale of oleomargarine, butterine, and spurious or adulterated butter. Under chief veterinary inspector Duncan McNab McEachran and his successor, John Gunion Rutherford, an effort was made to control disease in livestock, especially bovine tuberculosis. One method – the destruction of entire herds – remained controversial; individual farmers or inspectors were often unwilling to implement it because of the costs involved and the non-farming public failed to understand their reluctance. Only wealthy farmers could afford the destruction of an entire herd. Rutherford’s solutions, including the testing of imported stock, limited elimination of herds, and prohibitions against the export of infected cattle, gained acceptance. A national meat inspection program introduced in 1907 won the support of the packing industry.

One of the duties Fisher most enjoyed was to serve as an ambassador-at-large for Canada. He had recognized the significance of the Columbian exposition of 1893 for the promotion of trade and cultural exchange and, once in office, he made certain that Canada participated in subsequent events. He attended the universal exposition in Paris (1900), the national industrial exposition in Ōsaka, Japan (1903), the Louisiana Purchase exposition in St Louis, Mo. (1904), and the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific exposition in Seattle (1909). He hired the Canadian staffs, supervised the preparation of exhibits, and ensured that agriculture and emigration to Canada were featured.

As minister, Fisher attended agricultural fairs in England, Scotland, and Wales. He met fellow landowners and consorted with rural regenerators, such as Irish politician Sir Horace Curzon Plunkett. Elitists, these reformers advocated a major investment of human and financial capital in farmland and farming communities – through measures such as the teaching of scientific agriculture, manual training in rural schools, and the protection of water and land resources. Both Fisher and Robertson, who often travelled with him, sought to put Plunkett’s idealized concept of rural education into practice in Canada. Robertson was eventually able to persuade Montreal manufacturer Sir William Christopher Macdonald* to provide funding for projects in rural education. Closely connected with Fisher’s belief in rural regeneration was his growing pro-imperialist sentiment. He was a supporter of the Navy League of Canada, which wanted to strengthen naval ties between Britain and Canada, but he also envisaged closer economic and cultural ties, which rural regeneration might bolster. Writing to his mother in 1901, he had expressed the hope that in 100 years the Eastern Townships would resemble rural Britain, agriculturally.

Fisher carried his interest in conservation to other areas of activity. He had been a founding member of the Canadian Forestry Association in 1900. In February 1909, along with former cabinet minister Clifford Sifton and doctor and mp Henri-Sévérin Béland*, he represented Canada at an important North American conference on conservation called by American president Theodore Roosevelt and held in Washington. By April he had drafted and tabled in the commons legislation for the creation of the Commission of Conservation, based on one of the conference’s recommendations. Sifton was appointed chairman of the commission, but it was Fisher who defended it and spoke on its behalf in cabinet.

Another responsibility of Fisher’s department was the federal archives [see Douglas Brymner*; Sir Arthur George Doughty*] and he played an important role in securing a new building for the repository, opened in 1906; the following year he established the Historical Manuscripts Commission to advise the archives. Also in 1907, as acting minister of public works, he saw to the creation of the Advisory Arts Council. Set up in response to a request from the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, headed by George Agnew Reid*, it was to counsel the government on matters of art and to purchase works for the National Gallery.

Fisher’s department had a branch which administered the registration of copyrights, trade marks, industrial designs, and timber marks. He revised and amended the regulations of the Patent Office in 1904 and insisted on paying patent examiners as scientists. Between 1900 and 1910 he supported the initiatives of publisher George Nathaniel Morang* and economist James Mavor to protect Canadian authors and publishers from pirating by Canadian, American, and British printers. In 1910 he was a delegate to the Imperial Copyright Conference in London, England, to consider the ratification of international agreements.

By 1907 Laurier’s administration faced accusations of patronage and corruption from the opposition. A royal commission on the civil service, appointed that year, revealed negligence, confusion, and inadequacies. The government decided to act, and Fisher piloted important legislation through the house the following year to establish the Civil Service Commission. Michel Gordon La Rochelle and Adam Shortt* were appointed commissioners to oversee the operation of the legislation, supervise admissions and promotions, and administer examinations.

Unmarried and without a family of his own, Fisher had nonetheless demonstrated an early interest in education. He had served for some time in the early 1880s as a member of the district of Bedford’s board of examiners for teachers’ qualifications. In addition, he attended annual conventions of the Provincial Association of Protestant Teachers and held office as president in 1888. In 1901 he accepted a life membership on the Protestant committee of the Council of Public Instruction. George William Parmelee*, secretary of the committee, and Elson Irving Rexford*, Parmelee’s predecessor and confidant, drew Fisher into their campaign to consolidate schools in Protestant municipalities of Quebec. Fisher organized a private meeting in June 1906 at the Windsor Hotel in Montreal of selected school administrators, politicians, journalists, and Protestant committee members. They held a series of political-style meetings throughout the summer in Knowlton, Huntingdon, Richmond, Inverness, Lachute, and Ayer’s Cliff to promote their plans. Residents of the Eastern Townships perceived the rallies as designed to justify increased taxes and assert the influence of the McGill Normal School. Fisher continued to support the consolidation of rural schools until about 1919, but his participation may have damaged his reputation as a friend of rural inhabitants.

Fisher had won his riding by substantial majorities in the four general elections from 1896 to 1908. He had found an able organizer in Edward Caldwell and had stayed in touch with successive mlas in Brome. Newspapers in the Townships – with the exception of the Waterloo Advertiser – portrayed him as the head of a substantial spoils system. His power was not absolute, however. Laurier kept a certain amount of patronage to distribute himself. In addition, certain English-speaking Conservatives in the Knowlton area were tenacious in their opposition to him. Fisher’s actions in the so-called Dundonald affair illustrate the complexity of his position. In 1904 he temporarily replaced Sir Frederick William Borden* as minister of the militia and defence. In this capacity he refused to approve a militia appointment made by the general officer commanding, Lord Dundonald [Cochrane*], which concerned one of his Conservative opponents. After Dundonald publicly accused Fisher of partisanship, Prime Minister Laurier demanded and obtained the officer’s recall.

When the United States approached Canada in the spring of 1910 for a reciprocal trade agreement, Fisher may have been caught off guard. For much of his career he had promoted the lowering or elimination of the tariffs between the two countries. By 1910, however, he was temperamentally and philosophically a pan-Canadian and an Anglophile; he may not have shared the Liberal party’s enthusiasm for the American offer. Called on in late February 1911 to speak in the commons after Sifton, who differed with the Liberals over the issue and who spoke approvingly of the preferential tariff introduced in 1897 by William Stevens Fielding, which had favoured Great Britain, Fisher made do with a history of tariff debates to 1897. Laurier called an election later in 1911. During the campaign, Fisher argued that the Canadian-American agreement would only strengthen Canada’s ties to the British empire. He lost his seat to a young Conservative lawyer and militia officer in a wave of pro-imperial and anti-annexation sentiment.

During a fiercely contested by-election in Châteauguay in 1913, Fisher was again defeated. He remained active in the Liberal party, accompanying Laurier on tours and speaking at rallies. He continued to participate in school consolidation campaigns in Quebec, but after 1919 he turned his attention to moral education and compulsory school attendance at the national and provincial levels. Following Laurier’s death in 1919, he hosted a meeting at Alva of prominent Liberals to discuss the choice of a new party leader. As one of the country’s senior Liberals, he was considered a possible successor to Laurier, but he did not have a broad base of support. At the Liberal party convention held on 7 August, he withdrew early from the leadership race, bringing his vote and that of other prominent Quebec Liberals to William Lyon Mackenzie King*, who was chosen leader.

In failing health, Fisher wrote a will in 1919 setting up a trust fund of $100,000 to promote agriculture and the consolidation of Protestant schools in Brome County. Advised by Rexford that Protestant secondary-school teachers had no interest in teaching scientific agriculture in the way that he, Robertson, and Macdonald had hoped, and discouraged by local resistance to consolidation, he focused instead on strengthening Brome’s one-room schools and on prizes for agricultural fairs. He died in 1921 of a heart attack; his eulogy was delivered in Christ Church Cathedral, Montreal. The following year the board of trustees of the Fisher Trust Fund began to create a strong network of one-room schools that would last until 1946.

An elegant and cosmopolitan man, Sydney Arthur Fisher was nonetheless a strong believer in the virtues of rural life. He was an idealist, imbued with contemporary belief in progress and rural regeneration. He was also an able and practical Liberal politician and administrator who, as minister, did much to improve agriculture in Canada.

A list of several of Sydney Arthur Fisher’s speeches is in CIHM, Reg. One of his lectures, “Agriculture in the province of Quebec,” was published in British Assoc. for the Advancement of Science, Canadian economics: being papers prepared for reading before the economical section, with an introductory report (Montreal and London, 1885), 85–91.

ANQ-M, CE601-S109, 20 août 1850. LAC, MG 26, G; MG 27, II, D25. Private arch., R. E. Fisher (Montreal), P. S. Fisher, “Some notes on our ancestors” (typescript, n.d.). Montreal Daily Star, 22–23 Jan., 23, 25, 27–28 Feb., 8 May 1895. Montreal Herald, 10 April 1921. Observer (Cowansville, Que.), 2 Jan., 12 March, 21 May, 23 July 1908. Waterloo Advertiser (Waterloo, Que.), 4 Oct. 1901; 17 Jan., 11 April, 4, 11 July 1902; 18 March, 4 May 1904. Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1882–91, 1896–1911; Parl., Sessional papers, report of the Dept. of Agriculture, 1896–1910. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). CPG, 1881–91, 1897–1911. Raoul Dandurand, Les mémoires du sénateur Raoul Dandurand (1861–1942), Marcel Hamelin, édit. (Québec, 1967). R. MacG. Dawson and H. B. Neatby, William Lyon Mackenzie King: a political biography (3v., Toronto, 1958–76). Anne Drummond, “New educationists in Quebec Protestant model and intermediate schools, 1881–1926” (phd thesis, Univ. of Ottawa, 1994); “Sydney Arthur Fisher and the limits of school consolidation in Brome County, 1901–1921,” Journal of Eastern Townships Studies (Lennoxville, Que.), no.3 (autumn 1993): 31–47. Educational Record of the Prov. of Quebec (Montreal; Quebec), 4 (1884): 294; 8 (1888): 279–80; 16 (1896): 166; 41 (1921): 100. Sandra Gwyn, The private capital: ambition and love in the age of Macdonald and Laurier (Toronto, 1984). History of the federal electoral ridings, 1867–1980 (4v., [Ottawa, 1982?]), 3. Men of today in the Eastern Townships, intro. V. E. Morrill, comp. E. G. Pierce (Sherbrooke, Que., 1917). Carman Miller, The Canadian career of the fourth Earl of Minto: the education of a viceroy (Waterloo, Ont., 1980). H. B. Neatby, Laurier and a Liberal Quebec; a study in political management, ed. R. T. Clippingdale (Toronto, 1973). O. B. Rexford, The Fisher Trust Fund, 1922–1972 (n.p., 1974). Ronald Rudin, The forgotten Quebecers: a history of English-speaking Quebec, 1759–1980 (Quebec, 1985). O. D. Skelton, Life and letters of Sir Wilfrid Laurier (2v., Toronto, 1921). R. M. Stamp, “Urbanization and education in Ontario and Quebec, 1867–1914,” McGill Journal of Education ([Montreal]), 3 (1968): 127–35. Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell). The storied province of Quebec; past and present, ed. W. [C. H.] Wood et al. (5v., Toronto, 1931–32), 3: 199. E. M. Taylor, History of Brome County, Quebec, from the date of grants of land therein to the present time; with records of some early families (2v., Montreal, 1908–37), 1: 179, 181; 2: 228, 231.

Cite This Article

Anne Drummond, “FISHER, SYDNEY ARTHUR,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 21, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fisher_sydney_arthur_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fisher_sydney_arthur_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Anne Drummond |

| Title of Article: | FISHER, SYDNEY ARTHUR |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 21, 2024 |