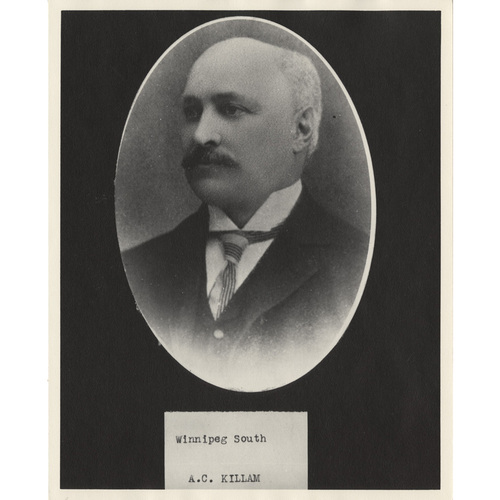

KILLAM, ALBERT CLEMENTS, lawyer, politician, judge, and railway commissioner; b. 18 Sept. 1849 in Yarmouth, N.S., son of George Killam, a sea captain, and Caroline Clements; m. 25 July 1877 Minnie Whyte in Windsor, Ont., and they had one son and one daughter; d. 1 March 1908 in Ottawa and was buried in St John’s cemetery, Winnipeg.

The grandson of Thomas Killam*, a prominent merchant and politician, Albert Clements Killam was raised in Yarmouth and earned his ba from the University of Toronto. He graduated in 1872 with silver medals in mathematics and modern languages, and was also the Prince of Wales medallist. After studying law with the firm of Crooks, Kingsmill, and Cattanach of Toronto [see Adam Crooks*], he was admitted to practice in Ontario as an attorney on 28 Aug. 1876, and as a barrister on 5 Feb. 1877. He began practice in Windsor, forming the firm of Horne and Killam in 1877 and launching a distinguished career. Early in 1879 he moved to new challenges in Winnipeg.

Killam quickly became an active member of the Winnipeg legal community; having been called to the Manitoba bar on 15 Feb. 1879, he issued his first writ only four days later. He appeared in several cases at the spring assizes and was soon known as “one of the ablest lawyers in Winnipeg.” In 1881 he became an examiner of the Law Society of Manitoba, and he served as a bencher of the society from 1882 to 1885. He was appointed qc by the governor general, Lord Lansdowne [Petty-Fitzmaurice*], on 9 May 1884.

After the federal Conservative government of Sir John A. Macdonald* disallowed legislation passed by the government of Premier John Norquay* authorizing the building of railway lines within the province, Killam ran as a Provincial Rights candidate in the election of January 1883. He defeated the Conservative candidate Charles Richard Tuttle by 63 votes in Winnipeg South. In the assembly he became a most vocal member of the opposition and also showed intense interest in all legal matters coming before the house.

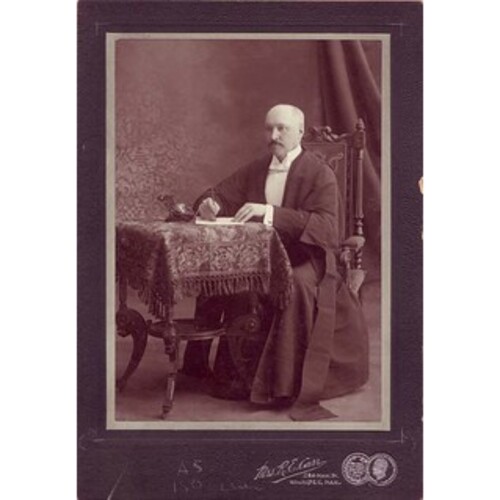

Following the sudden death of justice Robert Smith of the Manitoba Court of Queen’s Bench in January 1885, Macdonald abandoned for the occasion his usual policy of patronage and named Killam as Smith’s replacement on 31 January. The choice was widely acclaimed by the Manitoba bar and community because of the recognition given to an eminent Manitoban, and by the Canadian legal profession because of Killam’s obvious abilities. As a result of his wide knowledge of the law, his great industry, and his untiring patience, especially with junior counsel, he rapidly developed into an excellent, well-respected judge. Few possessed a more scrupulously judicial temperament. His written decisions were clear and convincing, and usually withstood the test of appeal to higher courts. In 1890 he upheld the right of the provincial government of Thomas Greenway to establish a single public school system and to abolish public financial support for denominational schools in Barrett v. the City of Winnipeg [see John Kelly Barrett*]. This decision was endorsed by all the judges of the Court of Queen’s Bench except Joseph Dubuc*, reversed by the Supreme Court of Canada [see Sir William Johnston Ritchie*], but ultimately confirmed by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. Earlier in his career, in September 1885, he had sat with the Manitoba Queen’s Bench, en banc, to hear the appeal of Louis Riel* from the decision of the magistrate’s court in The Queen v. Riel. He concurred in the judgement upholding the conviction. Leave to appeal to the Judicial Committee was denied, and Riel was hanged on 16 Nov. 1885.

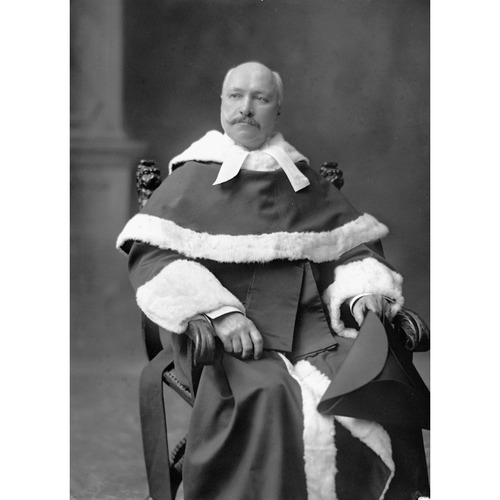

Killam became chief justice of the Court of Queen’s Bench on 12 April 1899, after Sir Thomas Wardlaw Taylor* retired, an appointment “unanimously approved by the Bar of the Province.” During his years on the Manitoba bench he maintained his interest in the legal profession by giving lectures to law students on equity and jurisprudence and by sitting on various committees of the Law Society of Manitoba, including one to revise the statutes of the province.

On the death of Chief Justice John Douglas Armour, Killam was named to the Supreme Court of Canada on 7 Aug. 1903. He was the first judge from western Canada to be appointed to that court. According to authors J. G. Snell and Frederick Vaughan, “Killam was chosen not simply because he was a westerner but also because he was an able jurist of long experience.” Once again his appointment was approved across Canada, even in Ontario, which had lost a seat on the court because of it.

Killam’s term as a Supreme Court justice was short, since he was persuaded to become chief commissioner of the Board of Railway Commissioners after the sudden resignation of Andrew George Blair in October 1904. When announcing the appointment on 6 Feb. 1905, Sir Wilfrid Laurier* stated that Killam “was qualified in every respect to discharge the important duties which would devolve upon him.” These quasi-judicial duties included the interpretation and enforcement of railway legislation and the regulation and adjustment of freight rates. Later, jurisdiction was extended to telegraph and telephone companies. There had initially been some doubt about Killam’s ability to carry out these onerous and unfamiliar tasks, but he soon convinced his critics that he had an excellent business sense as well as a first-rate legal mind. In his first year the board issued 1,000 orders and heard 353 cases. Killam, who was more than once called a “slave to duty,” handed down many elaborately written decisions. This heavy workload may have contributed to his sudden death from pneumonia at age 58. The passing of Killam, whom the minister of railways and canals, George Perry Graham*, called a “many-sided genius,” and about whom it was said that “there is no man on the judicial bench in whom the public has greater confidence,” was widely referred to as a “national loss.”

Arch. of Manitoba Legal Hist. (Winnipeg), Law Soc. of Manitoba files and photographs. Law Soc. of Upper Canada Arch. (Toronto), 1-5, barristers’ roll. NA, MG 26, A: 10099, 25390; G: 73910–11, 102429–36, 102578–81, 118997–99; RG 31, C1, 1861, 1871, Yarmouth (mfm. at Provincial Arch. of Alberta, Edmonton); 1881, 1891, Winnipeg (mfm. at Provincial Arch. of Alberta); RG 46, C. PAM, MG 12, E. Manitoba Free Press, 1879–July 1883, 31 Jan. 1885, 1888–89, 1899, 1901, 2 March 1908, 1909, 1916, 1925. Manitoba Weekly Free Press, 24 July 1903, 1904, 18 Nov. 1905, 1906. Ottawa Citizen, 2 March 1908. Winnipeg Daily Sun, 23 Dec. 1883. Canada Law Journal, 20 (1884): 177; 21 (1885): 65; 35 (1899): 291; 39 (1903): 497–98; 41 (1905): 205–6; 44 (1908): 129–30. Canadian Law Rev. (Toronto), 2 (1902–3): 656–57. Canadian Law Times (Toronto), 5 (1885): 64; 28 (1908): 309–10. “The jubilee of Sir James Aikins’ call to the Manitoba bar,” Canadian Bar Rev. (Toronto), 7 (1929): 231–38. Manitoba Reports (Winnipeg), 1 (1883–84)–7 (1890–91). SCR, vols.19, 33, 35. Snell and Vaughan, Supreme Court of Canada. Western Law Times of Canada (Winnipeg), 1 (1890–91)–6 (1895).

Revisions based on:

AO, RG 80-5-0-63, no.2379; RG 80-8-0-345, no.8173. J. S. Ewart, The Manitoba school question ... (Toronto, 1894).

Cite This Article

Lee Gibson, “KILLAM, ALBERT CLEMENTS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 23, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/killam_albert_clements_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/killam_albert_clements_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Lee Gibson |

| Title of Article: | KILLAM, ALBERT CLEMENTS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 2021 |

| Access Date: | November 23, 2024 |