Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

TOWNSHEND, GEORGE, 4th Viscount and 1st Marquess TOWNSHEND, army officer and artist; b. 28 Feb. 1723/24; d. 14 Sept. 1807 at Raynham Hall, Norfolk, England.

George Townshend was the eldest son of Charles, 3rd Viscount Townshend, and his wife Audrey Harrison. The Townshends owned extensive estates in Norfolk and elsewhere. George was educated at St John’s College, Cambridge, leaving there in 1742. He then went as a volunteer to the British army in Germany, being attached to the staff of Lord Dunmore, one of the general officers. He was present at the battle of Dettingen (16 June 1743) and also apparently at that of Fontenoy (30 April 1745), though a letter of Horace Walpole’s says that he was too late for the latter action. In May 1745 he was appointed a captain in Bligh’s Regiment (later the 20th Foot). On the outbreak of the Jacobite rebellion in that year he returned to Britain, joined his regiment, and fought with it at the battle of Culloden (16 April 1746). Thereafter he went back to the Continent, having been appointed an aide-de-camp to the Duke of Cumberland. In this capacity he was present at the battle of Laffeldt (21 June 1747) and carried Cumberland’s dispatch back to England. At this time he was elected to the House of Commons for the county of Norfolk, which he continued to represent until he succeeded his father as viscount in 1764. As of 25 Feb. 1747/48 he was appointed to a captaincy in the 1st Foot Guards, which carried with it the rank of lieutenant-colonel in the army. When the War of the Austrian Succession ended in 1748 he returned to England. He fell out with Cumberland, attacked him in parliament, and made him a victim of his notable powers as a caricaturist. At the end of 1750 he resigned from the army. He identified himself with the cause of militia reform and largely as a result of his efforts an effective new militia act was passed in 1757.

In the same year Cumberland ceased to be commander-in-chief, being succeeded by Sir John Ligonier. Townshend now returned to the service, being commissioned as colonel (of no specific regiment) as of 6 May 1758. In August he wrote to William Pitt asking for active employment against the French. In December he was summoned to London and appointed to command a brigade in the expedition under James Wolfe* which was being organized to attack Quebec by way of the St Lawrence. The appointment undoubtedly displeased Wolfe. He had asked Ligonier to let him choose his own subordinates, and he had not asked for Townshend. The “Proposals for the expedition to Quebec” in Pitt’s papers suggest as the three brigadiers Robert Monckton*, James Murray*, and Ralph Burton*. Burton, a friend of Wolfe’s, was now squeezed out to make room for a man with more influence. Wolfe wrote Townshend a welcoming letter in which he said, “Your name was mentioned to me by the Mareschal [Ligonier] and my answer was, that such an example in a person of your rank and character could not but have the best effects upon the troops in America; and I took the freedom to add that what might be wanting in experience was amply made up, in an extent of capacity and activity of mind, that would find nothing difficult in our business.” This reflects the feelings of a hard-working middle-class career officer confronted with the heir to a viscountcy who has always had things made easy for him. It would be strange if Townshend did not resent the reference to inexperience, especially as he had seen a good deal of active service. Here perhaps is the origin of later trouble.

Townshend, junior to Monckton but senior to Murray, was third in command of the expedition. He crossed the Atlantic with Wolfe in Vice-Admiral Charles Saunders*’s flagship Neptune. It may have been during the voyage that he made the water-colour drawing of Wolfe which the general’s biographer Robert Wright called “the most convincing portrait of Wolfe I have ever seen”; it is certainly the best portrait extant. In the last week of June 1759 the British fleet and army arrived before Quebec, and Wolfe began his long struggle with the problem of bringing the Marquis de Montcalm* to battle. On 9–10 July Townshend’s and Murray’s brigades landed on the north shore of the St Lawrence below Montmorency Falls and entrenched themselves there. By this time Wolfe’s relations with his brigadiers, and particularly Townshend, had deteriorated. On 7 July Wolfe had written in his journal, “Some difference of opinion upon a point termd slight & insignificant & the Commander in Chief is threatened wth Parliamentary Inquiry into his Conduct for not consulting an inferior Officer & seeming to disregard his Sentiments!” The “inferior Officer” was presumably George Townshend, mp. Things got worse after the unsuccessful Montmorency attack on 31 July, an operation which the brigadiers had disliked. On 6 September Townshend wrote the rather famous letter to his wife in which he said, “Genl Wolf’s Health is but very bad. His Generalship in my poor opinion – is not a bit better; this only between us.” Townshend’s wickedly clever caricatures of Wolfe which have survived tell a great deal about their relationship.

On or about 27 August Wolfe, then recovering from a severe illness, consulted the brigadiers formally for the first time. He sent them a memorandum begging them to consult together as to the best method of attacking the enemy. He himself suggested three possible lines of attack, all variants of the Montmorency operation which had already failed. After discussion with Admiral Saunders, the brigadiers (it is impossible to distinguish between the three as to their contributions at this point) politely rejected the commander-in-chief’s suggestions and recommended a quite different line of operation, bringing the troops away from Montmorency and landing above Quebec: “When we establish ourselves on the North Shore, the French General must fight us on our own Terms; We shall be betwixt him and his provisions, and betwixt him and their Army opposing General [Jeffery Amherst*] [on Lake Champlain].” For the first time, the essential strategic weakness of the French position was pointed out and exploited: Quebec, and the French army outside Quebec, were dependent on provisions brought down the river, and if this supply line were cut Montcalm would have no choice but to fight to open it. Wolfe accepted the brigadiers’ recommendation, and thereby made possible the victory on the Plains of Abraham; though the decision to take the risk of landing at the Anse au Foulon, close to the town, was Wolfe’s own. The brigadiers had favoured landing farther up the river.

In the battle of the Plains Townshend commanded the British left wing. Wolfe was mortally wounded and Monckton disabled, and Townshend unexpectedly found himself commanding the army. In these circumstances it is not surprising that his direction of the last phase of the action and its aftermath was not particularly effective. His first task was to deal with Colonel Louis-Antoine de Bougainville’s belated intervention from up the river; this was easily done. But the beaten French field army made good its escape across the Rivière Saint-Charles to its camp; and that night it marched around the British and got away to the west. Townshend prepared to besiege and bombard Quebec, bringing large numbers of guns up the cliff to the Plains of Abraham. But the city surrendered to him on 18 September. He had offered relatively lenient terms in order to get possession of it as soon as possible.

Murray was left in command at Quebec and Townshend returned to England before the winter. He was rewarded with the colonelcy of the 28th Foot and the thanks of parliament. During 1760 his conduct at Quebec was attacked and defended in anonymous pamphlets, which throw little real light on the happenings there. Effective 6 March 1761 he was made a major-general, and took command of a brigade in the British contingent of the allied army in Germany. His brigade was heavily engaged in the battle of Vellinghausen (15–16 July 1761). In 1762 he was sent to Portugal with the local rank of lieutenant-general, and took command of a division of the Anglo-Portuguese army which was protecting Portugal against the forces of France and Spain. No important operations took place here before the conclusion of peace.

In 1767 Townshend was appointed lord lieutenant of Ireland, and held this post until 1772. Traditionally, Townshend in Ireland has been remembered chiefly as a person who was adept at manipulating the Irish parliament by corrupt means and was considerably disliked. Recent research, however, reveals him as an effective and resolute administrator whose financial measures broke the power of the local oligarchy and transferred it to a party in parliament controlled by the government in Dublin Castle. From 1772 to 1782, and again for some months in 1783, he was master general of the Board of Ordnance. He was promoted general in 1782 and field marshal in 1796. He was appointed lord lieutenant of Norfolk in 1792, and also held the office of governor of Jersey. In 1787 he was made a marquess. In 1751 he had married Charlotte Compton, who was Baroness Ferrers of Chartley in her own right. By her, according to some authorities, he had four sons and four daughters. She died in 1770, and in 1773 he married Anne, daughter of Sir James William Montgomery and sister of William*; this marriage is said to have produced six children.

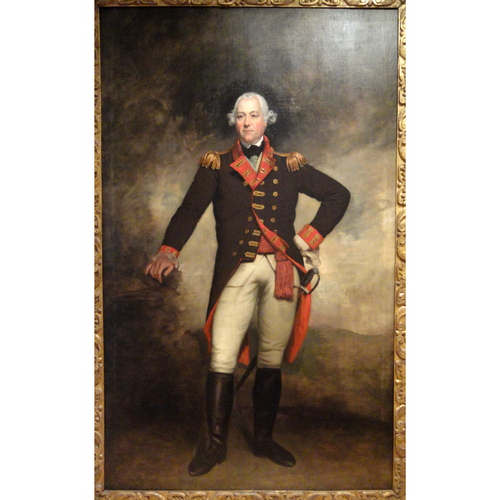

Although Townshend had been so bitter against Wolfe in 1759, time softened his feelings, and in 1774 he discouraged Murray from making an attack on the memory of the dauntless hero. Townshend and his fellow brigadiers have been much abused by Wolfe’s admirers; but there is not the slightest doubt that they gave him sound advice at a moment when he was floundering badly, and that it was they, with the support of Saunders, who set Wolfe’s feet on the path to victory. Townshend had important artistic abilities; he has been called “the first great English caricaturist.” An obituary in the Times said, “In his private character he was lively, unaffected, and convivial.” His portrait was painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds and by Thomas Hudson.

Townshend was one of the favoured people who in July 1767 received 20,000-acre grants in St John’s (Prince Edward) Island, being awarded Lot 56 in the east end of the Island. In 1770, embarrassed by his Irish expenses, he was trying unsuccessfully to sell this land. Like so many of the absentee proprietors, he seems to have done nothing to settle or develop his grant. In 1784, however, he gave up one-quarter of it to “American Loyalists and disbanded troops,” and some settlement then took place.

[The biography by Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Vere Ferrers (later Major-General Sir Charles) Townshend, The military life of Field-Marshal George, first Marquess Townshend, 1724–1807 . . . (London, 1901), is not good but contains important documents. It reprints, on pp.253–60 and 261–74 respectively, the two anonymous pamphlets published in London in 1760: A letter to an honourable brigadier-general, commander-in-chief of his majesty’s forces in Canada, subsequently ascribed to “Junius,” and A refutation of the letter to an honble. brigadier-general, commander of his majesty’s forces in Canada, attributed only to “An officer”; it also reproduces the Reynolds and Hudson portraits.

Townshend’s papers for the 1759 campaign are in the Northcliffe collection at PAC (MG 18, M, ser.2); see the printed calendar, The Northcliffe collection . . . (Ottawa, 1926). His portrait and caricatures of Wolfe are at the McCord Museum (M245, M905, M1443, M1791–94, M19856–57). The portrait has often been reproduced; it appears in colour in Robin Reilly, The rest to fortune; the life of Major-General James Wolfe (London, 1960). Six of the caricatures are reproduced in Christopher Hibbert, Wolfe at Quebec (London and Toronto, 1959).

A letter, dated 16 June 1770, from Townshend to Lady Townshend (his mother?) is in the Clements Library, George Townshend papers, letterbooks, 5. Among the printed primary and secondary sources, the following are valuable: John Stewart, An account of Prince Edward Island, in the Gulph of St. Lawrence, North America . . . (London, 1806; repr. [East Ardsley, Eng., and New York], 1967); Horace Walpole, Memoirs of the reign of King George the Second, ed. [H. R. V. Fox, 3rd Baron] Holland (2nd ed., 3v., London, 1846); The letters of Horace Walpole, fourth Earl of Oxford . . . , ed. [Helen] and Paget Toynbee (16v. and 3v. suppl., Oxford, 1903–25); Times (London), 19 Sept. 1807; Burke’s peerage (1963); DNB; G.B., WO, Army list, 1763, 1806; R. [R. ] Sedgwick, The House of Commons, 1715–1754 (2v., London, 1970), 2; Canada’s smallest prov. (Bolger); J. W. Fortescue, A history of the British army (13v. in 14, London, 1899–1930), 2; C. P. Stacey, Quebec, 1759: the siege and the battle (Toronto, 1959); Thomas Bartlett, “The Townshend viceroyalty, 1767–72,” Penal era and golden age: essays in Irish history, 1690–1800, ed. Thomas Bartlett and D. W. Hayton (Belfast, 1979), 88–112; “Viscount Townshend and the Irish Revenue Board, 1767–73,” Royal Irish Academy, Proc. (Dublin), 79 (1979), sect.C: 153–75. c.p.s.]

Cite This Article

C. P. Stacey, “TOWNSHEND, GEORGE, 4th Viscount and 1st Marquess TOWNSHEND,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 21, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/townshend_george_5E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/townshend_george_5E.html |

| Author of Article: | C. P. Stacey |

| Title of Article: | TOWNSHEND, GEORGE, 4th Viscount and 1st Marquess TOWNSHEND |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1983 |

| Year of revision: | 1983 |

| Access Date: | November 21, 2024 |