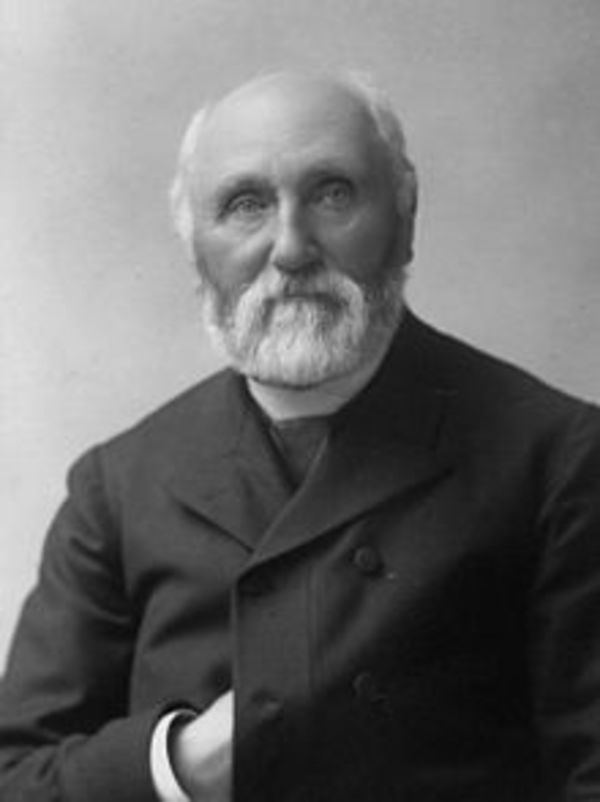

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

DUNCAN, WILLIAM, lay missionary; b. 3 April 1832 in Bishop Burton, England, son of Maria Duncan; d. unmarried 30 Aug. 1918 in New Metlakatla (Metlakatla), Alaska.

William Duncan was born, as they would have said in his native Yorkshire, on the “wrong side of the bed.” He was brought up by his maternal grandparents, and although his mother later married and had two daughters, he was never close to the family. At times ashamed of his own origins, he yet became the standard-bearer of Victorian Protestant Christianity on the northwest coast of North America. By the beginning of the 20th century he would be one of the most widely known missionaries in the English-speaking world.

Duncan grew up in the shadow of the great minster in the market town of Beverley. Educated in the local National School until the age of 14, he was taken on by George Cussons and Sons, a large tannery and wholesaler in hides and leather, where his grandfather was employed. Like other young men of his time and place he was intent on making his way in the expanding world of commerce. Guided by a paternalistic employer, stimulated by the ideas of lecturer Samuel Smiles, and with the practical assistance of the Mechanics’ Institute and evening classes, he continued his education. An avid reader of self-help and success literature, Duncan, like Smiles, valued the thrift, work, orderliness, and punctuality that led to both commercial success and personal advancement. Newly promoted to travelling salesman at age 21, he marvelled that he was now mixing with a “class of men far my superiors in education, rank and abilities and treated respectfully by them.” He attributed his good fortune to divine intervention. “When seated in a beautiful room surrounded with comforts and at a table covered with the good things of this world, . . . Oh! I used to feel my heart overflow in gratitude, for God’s wonderful love in thus elevating me.” For Duncan, his secular success could not have been achieved without religious transformation. It was a belief that was to be fundamental to his work amongst the Indians of the North Pacific.

Duncan had been a noted boy chorister at Beverley Minster and had spent many hours at choir practice or at evening and Sunday services. His lifelong love of church music derived from this experience, but a deep suspicion of ritual came from elsewhere. As a Sunday-school teacher, he had come under the influence of the Reverend Anthony Thomas Carr, an evangelical who thought that the Christian Church was composed of believers rather than denominations and who brought Duncan to the attention of the Church Missionary Society. After Carr’s unexpected death, Duncan, out of a sense of loss and obligation, offered himself to the evangelical CMS. From 1854 to the end of 1856 he trained as a missionary teacher, practising his craft in the model school attached to the society’s Highbury Training College for School-masters and in the missions to the “wretched neighbourhoods” of London.

The CMS gave organized expression to the beliefs of the age. England’s eminent position in the world, her colonies, and her commercial contacts all afforded “astonishing facilities for the wider dissemination of Gospel truth,” the Church Missionary Intelligencer asserted. “If our own age is the era for Missions, no less plainly is our own country the messenger-people to the whole earth. The Heathen cry, and they cry to us – to us Englishmen of the nineteenth century.” As both empire and church expanded their worlds, the Tsimshian of the North Pacific were drawn into the imperial net. It was Captain James Charles Prevost of the Royal Navy who called the attention of the CMS to the Indians of the Nass River (B.C.); it was the ambitious, earnest young schoolmaster whom the secretaries of the CMS selected to carry a practical Christianity to the Tsimshian.

Duncan arrived at Vancouver Island in June 1857 and spent the summer in Victoria where he met many of the colonial gentry. He lodged at the home of the Reverend Edward Cridge, the Hudson’s Bay Company chaplain, forming a strong relationship which was to have a lasting significance for his future. In late September he left for Fort Simpson (Port Simpson) on the Nass, where William Henry McNeill* was chief factor. On the insistence of Governor James Douglas* he took up residence at the HBC post. There were, he reported, some 2,300 Indians living around it [see Paul Legaic*]. He began the study of Tsimshian and confessed in a letter to Cridge that he felt “almost crushed with a sense of my position. My loneliness; the greatness of the work, which seems ever increasing before me. . . . at times seem ready to overwhelm me.”

From 1857 to 1862 Duncan remained dependent on the protection and hospitality of the HBC. He became proficient in Tsimshian, built a schoolhouse, and introduced elements of rote learning and physical drill to children and adults. He wrote with pride: “They can sing hymns and are learning God Save the Queen. . . . They have learnt how to speak in terms of civility to their fellowmen and have had several of their ways corrected.”

Like most other missionaries of his time, Duncan believed that large elements of the civilization he knew were part of Christianity. But he represented the CMS during the secretaryship of the Reverend Henry Venn, when the society aimed to offer a practical Christianity to its prospective converts. In his native church policy Venn urged his missionaries to integrate the religion into the mainstream of economic and political life where they worked. They were to be teachers, “prompters,” and “counsellors,” whose purpose should be to create a corporate Christian life and enable converts to rise in social position and influence while receiving Christian instruction. The native church policy required that missionaries such as Duncan become keen observers of the society they wished to change. They should recognize the power of the traditional governments but should consider that one of their most important tasks was to create a native leadership, a pastorate for the new native church. Throughout his life Duncan would argue that this was the policy he followed.

By the early 1860s at Fort Simpson, those Tsimshian who had chosen to ally themselves with Duncan, many of them young families, were discussing the possibility of returning to the old village of Metlakatla. Anxious himself to be rid of the HBC’s influence, Duncan was cautious about the move, wanting it to appear to be the decision of the people themselves. He recognized that the creation of a separate Christian village was to be his most significant step. It seemed to fulfil the first requirements of the native church policy and offered the prospect of a village “reflecting light and radiating heat to all the spiritually dark and dead masses of humanity around us.”

The utopia that he established at Metlakatla was to endure from 1862 to 1887 and to attract attention and adulation throughout the missionary world. It enabled William Duncan to exercise enormous personal power, both within the settlement and as adviser to various governments. It also brought prestige and prosperity to those Christian Tsimshian who were prepared to modify their way of life to create the new community.

Those who chose to become Metlakatlans were required to give up the outward signs of their own religion – “the Demoniacal Rites called Ahlied or Medicine Work: Conjuring and all the heathen practices over the sick; Use of intoxicating liquor; Gambling; Painting Faces; Giving away property for display; [and] tearing up property in anger or to wipe out disgrace.” They also had to observe the sabbath, send their children to school, build a house, cultivate a garden, pay taxes, and be “cleanly in habits . . . be industrious . . . peaceful and orderly [and] be honest and upright in dealing with each other and indians of other tribes.” What drew the Tsimshian to the settlement was in part the prosperity it was to offer, but also the certainty that the missionary promised in a time of political, economic, and physical insecurity for many of the coastal tribes.

Over the years Metlakatla took on the appearance of a European settlement. A large church, schoolhouse, and jail were landmarks. A small cannery and sawmill produced goods for export and for building. A trading store operated by Duncan replaced dependence on the HBC and remained at the economic heart of the community. For a time the mission also operated a schooner for trade and communications with Victoria, enabling Duncan to control external relations.

Although fishing, hunting, and some trapping stayed part of the village’s economy, its social life became increasingly Europeanized. A church choir, a brass band, a uniformed constabulary, a fire brigade, a Dorcas society for women, a reading-room, and adult education, all attracted a growing number of Tsimshian. Newcomers were required to abide by the laws of Metlakatla as well as by the new laws of the colonial governments and the Province of British Columbia. Duncan himself was appointed a magistrate, thus acquiring additional powers of persuasion, not only over the Tsimshian but over non-natives such as liquor sellers who posed a threat to the settlement.

By the mid 1870s Duncan had completed an internal reorganization of Metlakatla, dividing the men and women into ten companies whose purpose was to “unite the Indians for mutual assistance, to keep each member of our community under observation (surveillance), and to give opportunities to the majority of our men to be useful to the commonwealth.” Although Duncan argued this structure was a way of continuing to integrate new arrivals, it also shows the conjunction of economic cooperation, adaptation to Tsimshian needs, and authoritarian practices that was coming to characterize his enterprise.

Metlakatla attracted attention and brought financial support from England, the United States, and Canada. It spawned successful offshoots such as Kincolith and New Aiyansh and withstood competing enterprises of the Methodists [see Thomas Crosby] and the Salvation Army. Several missionaries were sent from Britain to assist, but Duncan quarrelled with or dispatched most of them, retaining the long-term allegiance of only the Reverend Robert Tomlinson and the Reverend William Henry Collison*. As the first missionary, he had become the confidant of many Tsimshian and exercised a wide influence. The determined young evangelist of 1857 had become a public figure as well as the architect of Tsimshian economic success. Until 1880 he was much fêted in England and in British Columbia for the model society he appeared to have created. He enforced his Metlakatla system with a rigid and at times harsh discipline. His forcefulness, perhaps inevitably, was transformed into a self-righteous and ill-advised truculence which led in part to the destruction of his utopia.

During the doctrinal dispute within the church at Victoria in the 1870s, Duncan supported his close friend and fellow evangelical, Cridge. After Bishop George Hills* removed Cridge from office as dean of the cathedral, Metlakatlans refused the bishop access to their village, and Duncan’s link with the Church of England weakened. This rupture also added to his personal reservations about accepting ordination and offering Holy Communion to the Tsimshian. What he had achieved had been done by a plain-spoken Yorkshire schoolmaster. The required robes of an ordained clergyman and the spiritual power accorded to him would not, he believed, enhance his position among the Tsimshian. He claimed that it was foolhardy in communion to offer the body and blood of Christ to the spiritually “unpredictable” Indians, a view he confirmed with some satisfaction after an outburst of unseemly religious enthusiasm followed the preaching of the newly arrived Reverend Alfred James Hall at Metlakatla in 1877.

Both Bishop Hills and the CMS were concerned by the Metlakatlans’ resistance to episcopal authority. A pastoral inspection by Bishop William Carpenter Bompas* of Athabasca in 1877–78 strengthened the growing sense in London that Duncan’s public success at Metlakatla had masked the dependence of the Indians on their missionary. Schooling, literacy, economic activity, social cohesion, and growing Europeanization had not produced Henry Venn’s native church. Duncan had created a city on the hill and a kind of Tsimshian Christianity. But he had become its guiding force, its heart and foundation, not the prompter and counsellor that Venn had desired. His creation had become unique, part of the Christian Church certainly, but less and less part of the Church of England.

The division in 1879 of the diocese of British Columbia relieved Hills of responsibility for the turbulent lay preacher in the north but brought a bishop, William Ridley, selected and supported by the CMS, to reside at Metlakatla in the new diocese of Caledonia. Meanwhile, Canadian expansion was bringing the Indian affairs branch, commercial salmon canneries, the overland telegraph, and other external influences that challenged the power and place of William Duncan. The continuing isolation of Christian converts would have been more and more difficult in the changing social and economic circumstances, but the presence of a bishop, an alternative source of authority and patronage, hastened the dissolution of the enforced self-conscious unity on which the Metlakatla system had been based.

Faced with an increasingly hostile Ridley, whom Duncan came to see as an extension of the “Church Party” in Victoria, he sought a formal independence from the CMS. Metlakatla had now become the native church the society had always desired, he argued. But the CMS by the 1880s was less impressed than it once had been by the heroic individualism of courageous missionary adventurers. Order, discipline, hierarchy, and Anglican rules were the code of the late-Victorian Christian imperialists. Henry Venn had died a decade before and Duncan’s request was met with the argument that the work at Metlakatla was still in its infancy, little progress had been made in recent years on the translation of the Scriptures into Tsimshian, no native pastorate existed, and “Church of England principles are the best with which to guide infant churches.” Duncan was asked in 1882 to return to England for consultation or to resign. That the CMS believed he could be brought to their terms suggests a bureaucracy triumphant. No one in British Columbia, friend or foe, would have expected him to resign. Most would have recognized that, as he wrote, his “labours for Metlakatla had made links between myself and the Indians too strong to sever.”

From 1882 to 1887 Metlakatla was a divided community. The majority of the Tsimshian, unaccustomed to challenging their missionary, supported Duncan. Perhaps a hundred, including some high-ranking families, supported the bishop. Disputes over buildings, land, and laws were bitter. Duncan and his adherents rejected the new Indian Act as inapplicable to their civilized community. They argued moreover that the land belonged to Metlakatlans and the CMS had no rights to the two acres of the village known as Mission Point, where the church and other buildings lay. As other Indians in the Nass and Skeena regions chose sides, and particularly as some took up the broader issue of aboriginal land rights in a province where no treaties with any government existed, the situation became explosive. Authorities in British Columbia, Ottawa, and London, unable to find a solution, watched in dismay as the Christian utopia, once the symbol of “moral and secular progress,” disintegrated.

In 1887, as in 1862, Duncan responded by creating a new community. Now, however, the Tsimshian moved not to an ancestral village, but to another land, where many feared becoming slaves of the local Indians. At New Metlakatla on Annette Island, Alaska, the school, cannery, store, sawmill, and social organization were reproduced and continued to attract the favourable attention of outsiders: Henry Solomon Wellcome and John William Arctander both published highly flattering accounts of Duncan and his work. The new tourist trade also brought many to Annette Island to witness firsthand the “civilized” Tsimshian and their martyr missionary.

By the turn of the century Duncan, now nearly 70, had become crippled by rheumatism, increasingly parsimonious, and markedly intransigent. He drew the reins of financial power closer to himself, opposed education beyond the age of 14 or outside the village, and fiercely resisted the attempts of the United States government to reduce his authority in the settlement. Metlakatla once again became a divided society. Some still adhered to their old teacher; others wanted change. Led by Edward Marsden, who was the son of Duncan’s first convert at Fort Simpson, the first of the community to receive higher education, and now a Presbyterian minister, they believed that the old man should be succeeded by a Metlakatlan and that the extensive property of New Metlakatla should be transferred to the Tsimshian. The subsequent disputes were even more bitter than those in British Columbia had been. Arrests, legal suits, and public denunciations formed the landscape of a struggle over money, power, and authority.

For Duncan, the opposition of Marsden had particular poignancy. Catherine Marsden, his mother, was Duncan’s long-time housekeeper. Edward, as a child, had learned Christianity at his mother’s knee and in the household of William Duncan. His experience of the outside world enabled him, as it did many in similar positions throughout the imperial world, to challenge the fundamental power that Europeans such as Duncan had so long enjoyed. Marsden’s struggle for modernity undermined the legitimacy of the master, and Duncan died as his control slipped away. The Tsimshian buried him beside the church in New Metlakatla, despite his wish to be interred next to Edward Cridge in Victoria. His estate was valued at $146,159, of which $138,679 was deposited in a bank at Seattle, Wash., money that most Metlakatlans believed belonged to their community.

Much was made in the 19th century of achievements by the individual missionary. Duncan, like David Livingstone, fitted the mould of the culture hero of his day. His personal embrace of evangelical Christianity had facilitated his own upward social mobility. For more than 20 years he was backed by a powerful missionary society, global in influence, and by the kinship networks of significant Tsimshian families. Their combined material and psychological support enabled this illegitimate son, this travelling salesman, small in stature and psychologically insecure, to accomplish more for his faith than he would have dared imagine. Yet his success brought not self-confidence but self-righteousness and a reluctance to relinquish power which was not uncommon in the racial confrontations that the history of Christian missionary work comprises.

Metlakatla Christian Mission (Annette Island, Alaska), William Duncan papers, esp. WD/C2146, Church Missionary Soc. to Duncan, 3 Dec. 1881; C2154, journal, 18 Feb. 1858; statement in reference to Metlakatla, London, 1886; C2158, notebook, “Laws of Metlakatla,” 15 Oct. 1862 (mfm. in Univ. of B.C., Special Coll. and Univ. Arch. Div., Vancouver). Church Missionary lntelligencer (London), 1849: 3, 76–77; 1852: 20; 1862: “Recent intelligence”; 1863: 195; 1881: 506. Peter Murray, The devil and Mr. Duncan (Victoria, 1985). Jean Usher [Friesen], William Duncan of Metlakatla: a Victorian missionary in British Columbia (Ottawa, 1974).

Cite This Article

Jean Friesen, “DUNCAN, WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 15, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/duncan_william_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/duncan_william_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jean Friesen |

| Title of Article: | DUNCAN, WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | January 15, 2025 |