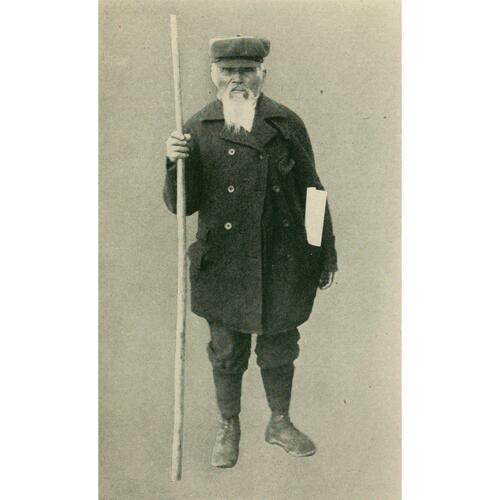

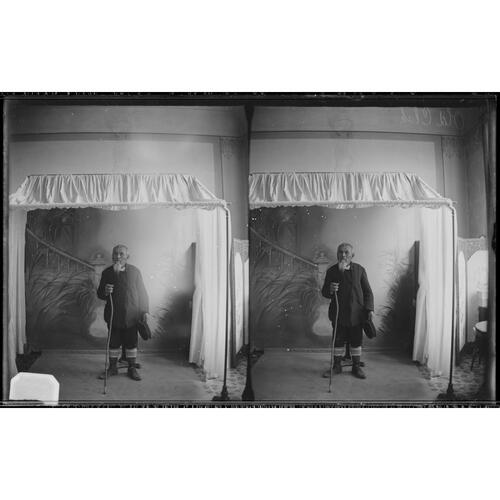

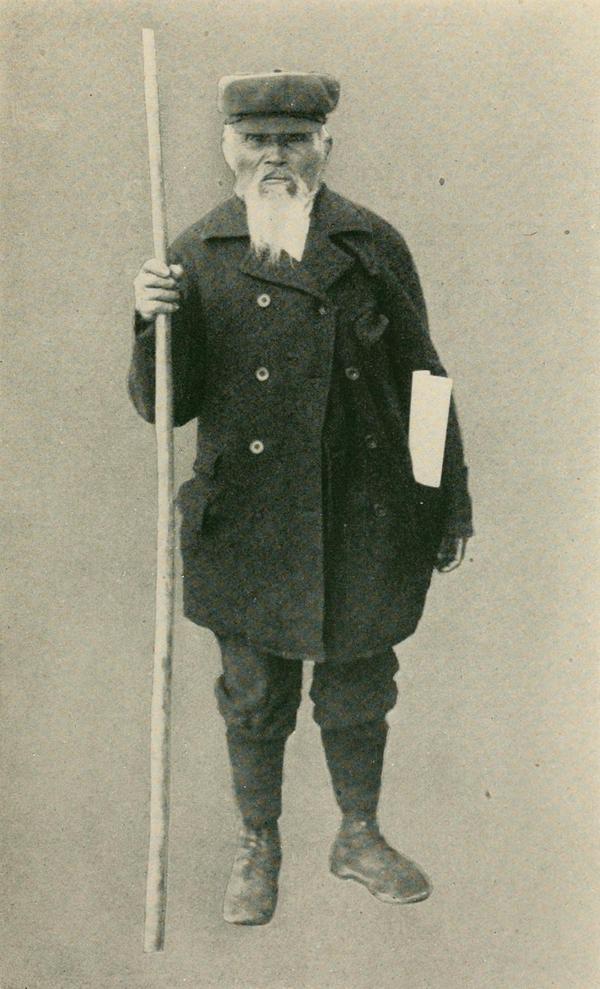

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

CLAH (Hlax), ARTHUR WELLINGTON (Temks, T’amks), Tsimshian chief, diarist, transporter, prospector, and fishery worker; b. 1831 at Laghco (Big Bay, B.C.); d. 1916 in Port Simpson, B.C.

Arthur Wellington Clah was born in the year that Peter Skene Ogden* of the Hudson’s Bay Company established a post at the mouth of the Nass River (B.C.). Eventually named Fort Simpson, it was later moved to the site of present-day Port Simpson. Although Clah’s birthplace was only a few miles from his final resting spot, his life expanded well beyond this area.

Clah is an anglicization of Hlax, only one of the Tsimshian names he held. He was of the killer whale clan and a member of the Gispaxlo’ots tribe; he was raised not by his father, who was from Kitselas, but by Guyagain, a member of the tribe’s eagle clan. Guyagain was killed when Clah was eight, and he was adopted by Txalaxath, also of the eagle clan. At Clah’s birth, the Gispaxlo’ots and the nine other coast Tsimshian tribes had villages in the vicinity of Metlakatla, south of Fort Simpson. These tribes were unique among the peoples of the northwest coast in that each possessed a village chief – the head of the highest-ranking house group – who, significantly, controlled trading prerogatives with neighbouring peoples.

In the 1850s Clah worked at Fort Simpson, where trade with the HBC was controlled by the Legaics [see Paul Legaic*]. With their consent and frequent involvement, Clah became an intermediary: using his trading prerogatives from house, clan, and tribe, he procured furs from Gitksan and Wet’suwet’en hunters in the interior and sold them to the HBC or private traders in Victoria. As well, he was often employed by the HBC to transport personnel and goods.

By 1858 Clah had taken as his principal wife a Niska, variously identified as Dorcas and Catherine Datacks, from Kitladamax on the upper Nass. She was the niece of Neshaki (Martha McNeill), a leading Niska woman and wife of William Henry McNeill*, who ran Fort Simpson for periods in the 1850s and 1860s. It was a propitious union for Clah since it provided or consolidated links with both the Niska and the HBC. The couple would have five sons and four daughters, but only two daughters would survive Clah.

As the native population declined as a result of Old World diseases, Clah moved from an economy rooted in the fur trade to a world of Indian reserves and wage labour. For instance, he worked at various jobs in Victoria and New Westminster for an 18-month period in 1859–60. What is unusual about Clah is that between 1861 and 1909 he kept an account of his transition, in the form of 40 daily diaries. In 1857 Anglican missionary William Duncan had arrived at Fort Simpson; in return for assistance with the Tsimshian language, he taught Clah, who became a Christian about 1861, to read and write. Although Clah’s diaries constitute a unique record among the native peoples of British Columbia, two problems complicate their use for historical reconstruction. His idiosyncratic use of the English language, grammar, and punctuation frequently make interpretation uncertain. It is usually possible to follow his activities, but motives and the complexities of social relationships are elusive. Secondly, some of the diaries were rewritten, and their content modified. Although the extent of this change is impossible to determine, other documentary sources can sometimes provide a check for Clah’s extraordinary record.

After Duncan had moved his mission to Metlakatla in 1862, Clah remained at Fort Simpson and other homes at the mouth of the Nass. His adherence to Christianity fluctuated but it revived in the early 1870s with the arrival at Fort Simpson of Methodist missionaries, notably Thomas Crosby. Although Clah’s family were baptized and he and Dorcas remarried in a Christian ceremony on 1 April 1875, they were never subservient to the missionaries. For a while in the 1890s Dorcas became a follower of the Salvation Army.

When the fur trade declined in the late 1860s, Clah had turned to new resource industries in northern British Columbia and Alaska. Gold discoveries took him to Omineca, Cassiar, and Juneau, as well as the Skeena and Nass valleys. Much of his time was spent transporting miners and supplies, but he engaged in some mining and prospecting activity, which he would continue into his sixties. During one visit to Juneau he produced and sold a series of stone carvings. In addition, Clah and his family became involved in salmon fishing and canning, work that was not always steady. In 1880s Clah complained to Duncan, with some exaggeration it seems, of being “very short in Grub and in clothing. . . . Sometimes works one day & sometimes paid me in tickets nothing paid But paper mony.”

By the 1870s Clah had assumed the chief’s name or title of Temks and was on his way to becoming a respected elder. The wealth he had accumulated through the fur trade and other ventures no doubt helped him ascend to this chieftainship. The process evidently meant giving potlatches, which Duncan opposed. On 24 Feb. 1868 Clah marked the end of his most elaborate feast – possibly given to celebrate his assumption of the name Temks – with an entry in his diary: “In this day at home I was spented all My Property. I gave away 6 or 7 hundred in goods give away all they stranger.” His role also involved participation in village councils and the land questions that engulfed the Tsimshian and their Niska neighbours, beginning in the 1880s.

Clah became an important repository of knowledge about Tsimshian society. In 1903 anthropologist Franz Boas* made an unsuccessful approach for his collaboration in researching Tsimshian mythology [see Henry Wellington Tate]. Clah planned to use his diaries to write his own history of the Tsimshian. The project did not proceed far, however, and the diaries were later purchased by philanthropist Henry Solomon Wellcome. Clah’s grandson William Beynon* (Kuskin), whom Clah had helped educate, became the principal ethnographer of his people. Together their records provide an invaluable source on the history of northern British Columbia before and after the arrival of whites.

With the exception of the volume for 1906, Clah’s diaries were purchased by Henry Solomon Wellcome in 1910, and are preserved in the collections of the Wellcome Institute for the Hist. of Medicine, London. Microfilm copies are available at NA, MG 40, F11. The 1906 diary is at BCARS, H/D/R13/C52, along with an undated notebook. Further documentation is provided in the author’s paper “The worlds of Arthur Wellington Clah, 1855–1881; an outline” (prepared for the British Columbia Hist. Geog. Research Project, 1993), a copy of which is in the DCB’s files.

Cite This Article

Robert Galois, “CLAH (Hlax), ARTHUR WELLINGTON (Temks, T’amks),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/clah_arthur_wellington_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/clah_arthur_wellington_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robert Galois |

| Title of Article: | CLAH (Hlax), ARTHUR WELLINGTON (Temks, T’amks) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |