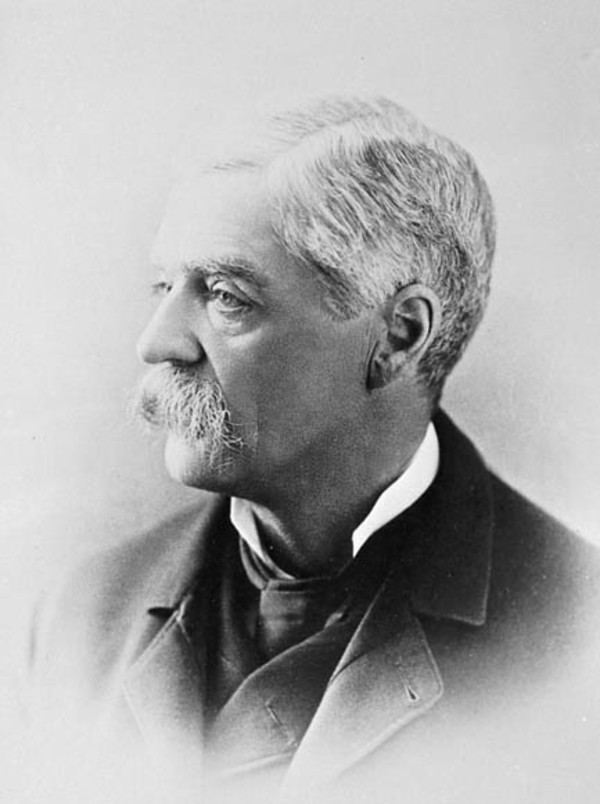

ANGERS, Sir AUGUSTE-RÉAL, lawyer, politician, judge, and office holder; probably b. at Quebec in 1837; m. there first 8 June 1869 Julie-Marguerite Chinic, and they had one daughter and two sons; m. secondly 16 April 1890 Émélie Le Moine, widow of Joseph-Arthur Hamel, in Sillery, Que.; they had no children; d. 14 April 1919 in Westmount, Que., and was buried 16 April in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery in Montreal.

An element of mystery surrounds the birth of Auguste-Réal Angers. His biographers generally agree that he was born at Quebec on 4 Oct. 1838, but no substantiating birth certificate has ever been found and the couple said to be his parents, François-Réal Angers* and Louise-Adèle Taschereau, were married in Sainte-Marie-de-la-Nouvelle-Beauce (Sainte-Marie) on 4 April 1842. His own marriage certificate only adds to the mystery since it makes no mention of his parents. All indications are that Angers was born in 1837; indeed, the 1901 census lists his birth at Quebec on 4 Oct. 1837. The key to the mystery may be in the records of Notre-Dame de Québec parish, which include a baptismal certificate for “Casimir Auguste de Saint-Réal,” born 4 Oct. 1837 in Beauport of unknown parents. This child could well have been the boy whom François-Réal Angers and Louise-Adèle Taschereau raised as their own son.

Angers studied at the Séminaire de Nicolet from 1849 to 1856 and was later an unregistered student in law at the Université Laval. He evidently obtained his legal training from his father. On being called to the bar of Lower Canada on 2 July 1860, Angers joined Louis-Napoléon Casault and Jean Langlois in one of the most prosperous law firms in Quebec City. Soon he had acquired all the prerequisites for a career in politics.

The opportunity arose in February 1874. Angers easily won a provincial by-election in Montmorency for the Conservatives. Then came the Tanneries scandal [see Louis Archambeault*], which caused the resignation of Gédéon Ouimet*’s cabinet. Charles Boucher de Boucherville, who was called on to form a new government, chose Angers as solicitor general. The Liberals soon discovered that the new minister was not simply the beneficiary of circumstances. At the beginning of the first session Angers replied to the leader of the opposition on the subject of the Tanneries affair. Shortly afterward he supported a plan for electoral reform which included introduction of the secret ballot. He quickly gained a reputation as a debater. In the 1875 general election, no one dared run against him. He became government leader in the Legislative Assembly in November 1875 and attorney general in January 1876.

In the space of 18 months he had consolidated his position as the central figure in the cabinet. Since the premier sat in the Legislative Council, Angers represented the ministry in the assembly. It was he who steered major pieces of legislation through the house, including one dealing with the important question of the North Shore Railway. When private firms proved incapable of building the line, the government took matters in hand with the support of a number of municipalities, including Quebec and Montreal which pledged a million dollars each. But the project became complicated after the government made changes in the original route. Some discontented municipalities threatened not to honour their commitments, and early in 1878 Angers got a bill passed forcing them to do so, a move that strengthened his reputation for toughness and intransigence.

These incidents might not have attracted attention had they not been highlighted by the presence of a new actor on the political stage. Luc Letellier* de Saint-Just had been appointed lieutenant governor by the Liberal government of Alexander Mackenzie* in 1876. Angers’s complimentary remarks about him deceived no one in the legislature. The two men clashed on several occasions and in the end it was the North Shore Railway, by then known as the Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa and Occidental, that precipitated the crisis. The lieutenant governor criticized the premier for not having consulted him on either this matter or a bill introducing new taxes. In fact he was annoyed at Boucher de Boucherville for not having followed his recommendations on public expenditures. On 2 March 1878, to everyone’s surprise and without any explanation, Angers moved that the house adjourn although it had been sitting for only minutes. At that very moment Boucher de Boucherville was at Spencer Wood, where Letellier de Saint-Just had just dismissed him from office.

The Liberal government of Henri-Gustave Joly*, hastily put together by a minority party, found itself in a precarious position after the next election, but the strong man of the Boucher de Boucherville ministry was gone from the house. Having lost by 14 votes to Charles Langelier, Angers refused the seat offered him by Joseph-Israël Tarte* and turned to settling accounts with Letellier. He even neglected his business at Quebec in order to ensure that the federal government dismissed Letellier, a step it took in July 1879.

When the Joly government fell in the autumn of 1879, Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau* was called on to form a cabinet and Angers reportedly refused to serve under him. A widower since 11 January, he agreed to run as a federal candidate instead when his friends urged him to assume the mantle of Sir George-Étienne Cartier*. He won the seat for Montmorency in a by-election on 14 Feb. 1880, but took little part in debates. According to Tarte, he did not enjoy the ambience of the federal parliament, and Hector-Louis Langevin* “took a dislike to him.” On 13 Nov. 1880 he was appointed puisne judge of the Superior Court for Montmagny district.

Settled near the St Lawrence in the former presbytery of the curé of Berthier (Berthier-sur-Mer), Angers could have lived out his life on the bench, dividing his leisure between reading and his passion for yachting, but his friends kept pressing him. In the autumn of 1887 he finally accepted the office of lieutenant governor.

Angers’s political enemies would seize the chance to write that this appointment was intended to put obstacles in the path of Premier Honoré Mercier* and secure his dismissal at the first opportunity. An examination of the facts does not necessarily lead to this conclusion. Until 1889 Mercier still acknowledged that the lieutenant governor was overseeing public affairs “in an intelligent manner, but without ever deviating from the constitutional rules.” Mercier is also believed to have used his influence at Rome to get him awarded the grand cross of St Gregory the Great. Angers, for his part, seemed to be trying to avoid a confrontation. In 1888, for instance, he expressed reservations about a plan to convert the debt, but went no further lest he attract the attention of the Liberal press. On two occasions he consulted Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald* to get his advice before acting. Even in January 1891, when he considered the Mercier government “extravagant and very often unconstitutional,” he cautioned Macdonald against the idea of naming a man as undiplomatic as Langevin to be the next lieutenant governor.

The crisis came nevertheless. In August 1891 witnesses summoned before a Senate committee revealed that Ernest Pacaud*, an organizer for Mercier, had “held back” for the election fund $100,000 of the $175,000 paid by the government to a railway company. Angers asked Mercier for an explanation, proposed a commission of inquiry, and ordered the premier to confine himself to “urgent administrative measures.” In his reply Mercier disclaimed responsibility for actions Pacaud had taken without his knowledge, but Angers was adamant. He insisted on an inquiry by a commission of his own choosing and rejected the idea of a legislative one. On 15 December, with chairman Louis-Amable Jetté absent because of illness, two of the three commissioners submitted a preliminary report in which they censured Pacaud’s action, but since they could not prove personal responsibility on Mercier’s part, they exonerated him, along with four ministers. Without waiting for the opinion of Mr Justice Jetté, who had already dissociated himself from his colleagues’ conclusions, Angers dismissed Mercier on 16 December and asked Boucher de Boucherville to form a cabinet.

Angers could easily have disappeared from public view at that point. In January 1891 Macdonald had offered him an important position. Macdonald’s successor then invited him to join the federal cabinet, but Angers refused in order not to give the conspiracy theory credibility. The Conservative victory in the provincial election of March 1892 lent an air of legitimacy to Mercier’s dismissal, and in December 1892 Angers accepted a seat in the Senate and the agriculture portfolio in the cabinet of Sir John Sparrow David Thompson*.

Scarcely had Angers assumed office when he took a stand on the thorny Manitoba school question [see Thomas Greenway*]. He committed himself to restoring to Roman Catholics the schools abolished in 1890. Although after Thompson’s sudden death there was increased pressure on Sir Mackenzie Bowell, his successor, the new prime minister announced on 8 July 1895 – through his minister of finance, George Eulas Foster* – that his government would not have remedial legislation passed before the next session. Angers and two other cabinet ministers, Sir Adolphe-Philippe Caron* and Joseph-Aldric Ouimet, had not taken part in making the decision and they resigned that very day. Caron and Ouimet, however, yielded to pressure and withdrew their resignations. Angers remained adamant. On 11 July he gave his reason for leaving the cabinet: the government’s inaction dangerously compromised the passage of a remedial measure and he could not accept this risk.

After his colleagues had capitulated, Angers put up a bold front, even refusing a comfortable seat on the Supreme Court of Canada. However, he evidently was not inclined to keep up the pressure on the government, which soon collapsed because of resignations. Bowell was replaced by Sir Charles Tupper, who brought Angers back into the cabinet as president of the Privy Council. The Conservatives were crushed in the next general election and Angers lost in Quebec Centre to François Langelier. Tupper tried to reappoint him to the Senate seat he had resigned, but the governor general refused.

Angers moved to Montreal, where at the age of 59 he had to resume practising law. He would have to wait until the Conservatives’ return to power in 1911 for another lucrative public office, that of legal counsel to the Montreal Harbour Commission. On 1 Jan. 1913 he was made a kcb.

When Sir Auguste-Réal Angers died in 1919, journalist Omer Héroux* was convinced that his 1895 resignation would be remembered as “the high point of his career.” Instead, his name remains associated with the dismissal of Mercier, a courageous act according to the Conservatives, an unconstitutional and dictatorial decision according to the Liberals, and a partisan settling of scores according to a number of observers. But whether he was right or wrong in taking a step similar in many respects to Letellier’s “coup d’état” of 1878, it is unlikely that such a strong-minded man would have let himself be forced into a line of conduct contrary to his ideas and his principles.

AC, Montréal, État civil, Catholiques, Cimetière Notre-Dame-des-Neiges (Montréal), 16 avril 1919. ANQ-Q, CE1-1, 5 oct. 1837, 8 juin 1869; CE1-58, 16 avril 1890. NA, MG 27, I, C1 (photocopies at ANQ-Q). Le Devoir, 15 avril 1919. Le Monde illustré (Montréal), 2 mai 1891. La Presse, 15 avril 1919. F.-J. Audet et al., “Les lieutenants-gouverneurs de la province de Québec,” Cahiers des Dix, 27 (1962): 227–30. J.-C. Bonenfant, “Destitution d’un premier ministre et d’un lieutenant-gouverneur,” Cahiers des Dix, 28 (1963): 9–31. Canada Gazette, 20 Nov. 1880: 582; 29 Oct. 1887: 990; 24 Dec. 1892: 1186; 2 May 1896: 2074. Canadian biog. dict. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). Thomas Chapais, “A. R. Angers,” trans. W. O. Farmer, Men of the day: a Canadian portrait gallery, ed. L.-H. Taché (32 ser. in 16v., Montreal, 1890–[94]), 16th ser. Chemin de fer de la baie des Chaleurs; dossier officiel complet: correspondance officielle entre son honneur le lieutenant-gouverneur et M. Mercier, premier ministre (Québec, 1891). Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.2. J.-A.-I. Douville, Histoire du collège-séminaire de Nicolet, 1803–1903 . . . (2v., Montréal, 1903). DPQ. J. [A.] Macdonald, Correspondence of Sir John Macdonald . . . , ed. Joseph Pope (Toronto, 1921), 420–21, 423–27. Qué., Assemblée Législative, Débats, 1874–78, 1889. P.-G. Roy, Les avocats de la région de Québec; Fils de Québec (4 sér., Lévis, Qué., 1933), 4: 170–72; Les juges de la prov. de Québec. Rumilly, Hist. de la prov. de Québec, vols.2, 5–8. J. T. Saywell, The office of lieutenant-governor: a study in Canadian government and politics (Toronto, 1957), 96–97, 122, 128, 204. J.-I. Tarte, 1892, procès Mercier: les causes qui l’ont provoqué, quelques faits pour l’histoire (Montréal, 1892).

Cite This Article

Gaston Deschênes, “ANGERS, Sir AUGUSTE-RÉAL,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 12, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/angers_auguste_real_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/angers_auguste_real_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Gaston Deschênes |

| Title of Article: | ANGERS, Sir AUGUSTE-RÉAL |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | November 12, 2024 |