Source: Link

FOX (Foxe), LUKE, English navigator and arctic explorer, son of Richard Fox, master mariner of Hull; b. 20 Oct. 1586 in Kingston-upon-Hull, Yorkshire; married Anne Barnard, of Whitby, 1613 (there is no record of any children); d. c. 15 July 1635.

Fox’s formal education was limited but he became well read in navigation and arctic history. As a youth he sailed in European waters and acquired ability, as he says, in “the use of the globes and other mathematicke instruments.” By the age of 20 he was fascinated by the possibility of discovering a northwest passage to the Orient. Gaining the patronage of Henry Briggs, the mathematician, and Sir John Brooke, late in 1629 he petitioned King Charles for assistance in a voyage. He was successful, and the stimulus of a rival plan of Capt. Thomas James at Bristol won Fox the further support of a group of London adventurers, including Sir Thomas Roe.

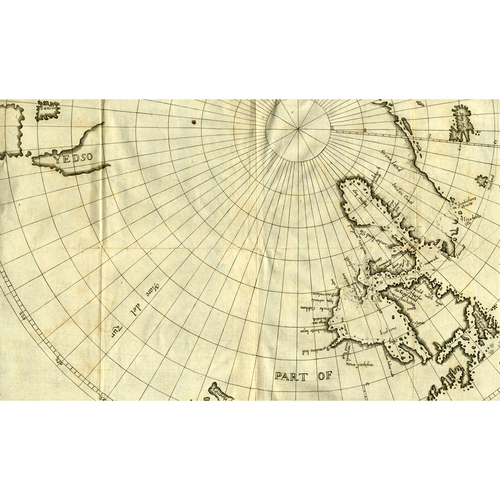

Preparations advanced with Fox’s usual thoroughness, and H.M.S. Charles, a pinnace of 70 or 80 tons, with 20 men, 2 or 3 boys, and 18 months’ provisions, left London 28 April 1631 (MS journal), quitting Deptford 5 May (published journal), 2 days after James left Bristol. Fox was captain and pilot. By way of the Orkneys, Fox reached Hudson Strait 22 June, skirted the western shore of Hudson Bay “never without sight of land,” but discovered no likely opening (he apparently missed Chesterfield Inlet). At Port Nelson he found relics of Sir Thomas Button’s 1612–13 wintering. He met James by chance, 29–31 August, near Cape Henrietta Maria, turned north, and was the first to sail beyond Foxe Channel (named by Parry* nearly 200 years later) into Foxe Basin. He followed the coast of what is now Foxe Peninsula, making soundings and tidal observations all the way, to the point he named Cape Dorchester, the land about being whimsically dubbed (22 September) “Fox his farthest” and by his reckoning just beyond the Arctic Circle (66º47´N) but more likely about 1´ south of it. Turning homeward, he reached the English Channel 31 October, “Having beene forth neere 6 moneths.”

Fox did not discover a northwest passage, though he considered what is now Roes Welcome Sound promising. He cancelled the last hope for Hudson Bay, and found the tide through Foxe Channel to be from the southeast (not from the west, as Henry Hudson and Button had encouragingly reported); these were negative discoveries, but they abated the zeal for arctic exploration for almost 200 years. Moreover, he writes that he had gone farther than any predecessor “in lesse time and at less charge.” His return in the same year undoubtedly saved lives (his genuine concern) and money, but it gave rise to adverse criticism, and Fox found it necessary to append a defence to his book.

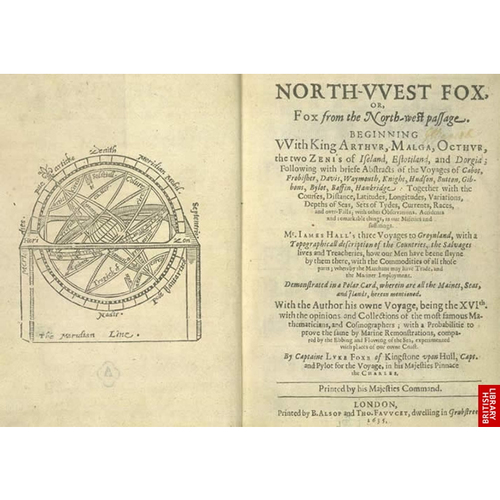

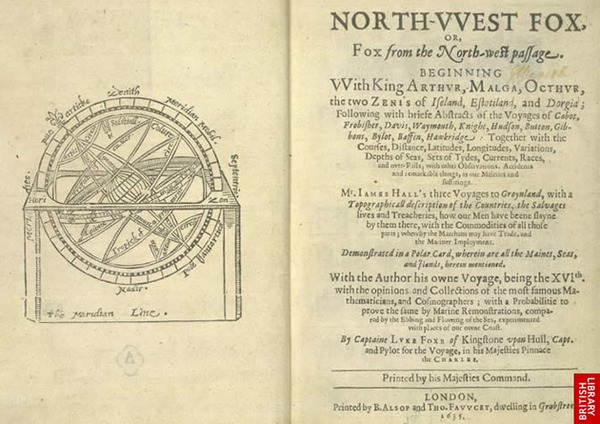

This work, fancifully named North-West Fox . . . (London, 1635), is now rare, excessively so with Fox’s circumpolar map, described by C. H. Coote (DNB) as “one of the most interesting and important documents in the history of Arctic exploration.” The British Museum has a copy of an MS version of Fox’s narrative. The book begins with a review of arctic explorations, perhaps the first ever attempted, including the only contemporary account of Button’s great voyage to Hudson Bay. The journal of Fox’s own voyage illustrates the span of his curiosity, embracing observations on tides, soundings, ice formations, aurora, and arctic flora and fauna. He describes a native burial ground on an island he named Sir Thomas Roe’s Welcome (now applied to the encompassing strait). In the same vicinity he honoured other patrons in naming islands Brooke Cobham (now Marble Island) and Brigges His Mathematickes (now disused). His geographical designations are numerous; Christy (p. cix) lists 27 of them, 8 surviving in usage. North-West Fox, which Markham aptly calls “the quaintest and most amusing narrative in the whole range of Polar literature,” Fox himself recognized as being “rough hewn.” Self-made, he was somewhat vain and pedantic, but a diligent researcher and an able navigator, being one of the first to use logarithms (learned from Briggs) in his navigation and to write of the use of log and line in measuring a ship’s run.

Though he was frugal and temperate, the years after his voyage were spent in poverty, “having received neither sallery, wages, or reward.” Perhaps if he had lived on after the publication of his book he might eventually have benefited; but he died in unmerited neglect a few months after it appeared.

North-West Fox . . . has been reproduced in Voyages of Foxe and James (Christy). Dodge, Northwest by sea, 156–64. DNB. C. R. Markham, The lands of silence (Cambridge, Eng., 1921), 151–56. Narratives of voyages towards the North West in search of a passage to Cathay and India 1496 to 1631, . . . , ed. Thomas Rundall (Hakluyt Soc., 1st ser., V, 1849), 152–86. Oleson, Early voyages, 169–70.

Cite This Article

William F. E. Morley, “FOX (Foxe), LUKE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fox_luke_1E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fox_luke_1E.html |

| Author of Article: | William F. E. Morley |

| Title of Article: | FOX (Foxe), LUKE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1966 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | March 30, 2025 |