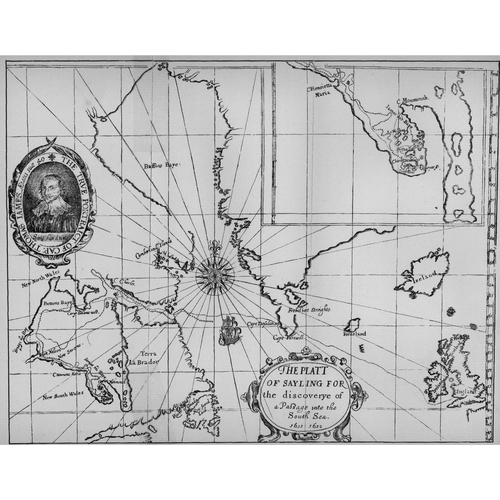

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

JAMES, THOMAS, Welsh navigator, explorer, and author who, in 1631–32, explored the west coast of Hudson Bay and James Bay in an attempt to find a northwest passage; b. 1593?; d. 1635 or early 1636.

Little is known of James’s ancestry and early life; however, it is now doubtful that his antecedents were in Bristol although he spent part of his adult life in the city. Available evidence indicates that he was the second son of James ap John Richard of Wern-y-cwm, Wales, and Elizabeth Howel and was brought up in a Welsh border parish near Abergavenny in Monmouthshire. He was a barrister before he turned to the sea and was probably wealthy.

James’s opportunity to head a northwest passage expedition arose through the commercial rivalry between London and Bristol merchants. Capt. Luke Fox had persuaded a group of London merchants to support him in a search for a northwest passage. The Bristol Society of Merchant Venturers determined to send a similar expedition, for they feared the London merchants might secure a monopoly of whatever markets or trade Fox might discover. Capt. James represented the Bristol merchants at court and obtained for them from Charles I a promise of equal rights and privileges in whatever discoveries either expedition might make, in proportion to each city’s investment in the dual venture.

On 3 May 1631, James sailed from Bristol in a 70-ton ship, named Henrietta Maria after England’s queen, with a crew of 22 men. He took no one who had ever sailed on a northern voyage for fear that opinion based on previous experience might conflict with or diminish his own authority. On 5 June the ship entered the ice near Davis Strait and there James and his men began an almost uninterrupted series of harrowing adventures.

They took nearly a month to penetrate Hudson Strait, and ice prevented them from proceeding farther north than Nottingham Island. On 16 July James turned southwest into Hudson Bay and, on 11 August, after a miserable crossing, he sighted Hubbert’s Hope, near present-day Churchill.

During the latter part of July, James and Fox separately explored the Hudson Bay coast south of Cape Churchill, a coast James named the New Principality of South Wales. On 26 July James lay in the estuary of a great river that he named the New Severn. On 29 and 30 July occurred the only meeting of James and Fox in Hudson Bay, a meeting that Fox records with scorn.

On 3 September James sighted and named Cape Henrietta Maria and on the 7th he began his only independent exploration, a reconnaissance of the west coast of the bay to which he gave his name. James planned to plumb this bay, to round “Cape Monmouth” (a non-existent projection of land that he imagined separated an “east” bay from the “west” bay which Henry Hudson had discovered and in which he had perished), and then to seek a route to the St. Lawrence River. In early October, greatly troubled by storms, shoals, and ice, James sought an anchorage and found one off Charlton Island, where he wintered – the first deliberate wintering of a European party in the Canadian north.

During October and November, the crew built cabins on the island. On 29 November James sank his ship in a desperate move to prevent its being swept away by storms. Fearing the ship could not be raised again, he attempted to build a pinnace of local wood during the winter. Because of inexperience and inadequate provisions and clothing, James and his men suffered from cold and malnutrition. By February 1632, most of the crew showed symptoms of scurvy. Four men died. Throughout these tribulations, James carefully recorded scientific information, taking special note of low-temperature phenomena.

In April, the party discovered to their surprise that the sea had not frozen solid and that water drained from the ship’s hold at low water. They repaired the damaged hull and pumped out the ship. During May they complained of the daily heat, although the nights continued freezing cold. In June they rehung the rudder with great difficulty and moved the ship into deeper water. They had restored their health by eating green plants found along the shores. Mosquitoes, they learned, were a more painful affliction than the cold of winter.

On 24 June 1632, James took possession of Charlton Island in the king’s name. On 1 July, when the expedition took formal leave of its dead, James recited a poem he had written for the occasion, a poem that Robert Southey praised in his Omniana (1812). The next day, on Danby Island, James found two stakes that “had beene cut sharpe at the ends with a hatchet, or some other good Iron toole, and driven in, as it were with the head of it.” These stakes were possibly relics of Henry Hudson and his men, who had been abandoned thereabouts some 20 years earlier.

Hindered by severe ice conditions, the ship took nearly three weeks attaining Cape Henrietta Maria and approached Cape Tatnam only on 14 August. James then sailed northeast across Hudson Bay and, on the 24th, sighted Nottingham Island. He attempted to penetrate what is now called Foxe Channel, not knowing that his rival had explored it on his homeward trip the previous year. James reached about 65°30′N before he turned back. The Henrietta Maria arrived at Bristol on 22 October in such a state that her crew had thought it a daily miracle that she did not sink.

Of the two voyages, Fox’s was the more productive in geographic discovery, and it was easily executed; Fox’s rough common sense and professional seamanship are in strong contrast to James’s academic qualities and his amateurish misadventures. But James’s narrative, a literary success, had the greater popularity. Some critics think that Coleridge drew upon James’s account of hardship and lamentation in writing The rime of the ancient mariner. Robert Boyle quoted many passages from it in New experiments and observations touching cold (London, 1665).

James rightly concluded that no northwest passage existed south of 66°N. This conclusion and the account of his sufferings in James Bay so discouraged promoters of expeditions seeking a northwest passage that the search, begun by Frobisher in 1576, was interrupted until 1719 when James Knight* began a new chapter in northwest-passage exploration. There was no recorded voyage into Hudson Bay, after James, until 1668, when Chouart Des Groseilliers and Zachariah Gillam accomplished the fur-trading mission that resulted in the formation of the HBC.

Upon his return from Hudson Bay, the Admiralty appointed James to a command in the Bristol Channel squadron. His will is dated 28 Feb. 1635, and he may have died that spring. He must have predeceased his elder brother, John, who died in April the following year. His place of burial is uncertain. James’s knowledge of mathematical navigation was unusual for the time. His account of his voyage, one of the classic narratives of exploration, demonstrates the author’s fluent grace of expression, learning, and scientific curiosity.

Records relating to the Society of Merchant Venturers of the city of Bristol in the seventeenth century, ed. P. McGrath (Bristol Record Soc., XVII, 1952). Voyages of Fox and James (Christy): see Introduction, I cxxxi-ccix, and James’s “The strange and dangerous voyage of Captaine Thomas James, in his intended discovery of the northwest passage into the South Sea wherein the miseries indured, both going, wintering, returning; & the rarities observed, both philosophicall and mathematicall, are related in this journall of it,” II, 447–611. DNB. Dodge, Northwest by sea. C. M. MacInnes, “The north-west passage,” in A gateway of empire (Bristol, 1939), 107–23. J. F. Nicholls, Capt. Thomas James and George Thomas, the philanthropist (Bristol Biographies, II, 1870). Oleson, Early voyages, 169–70. J. W. Damer Powell, Bristol privateers and ships of war (Bristol, 1930).

Revisions based on:

W. K. D. Davies, Writing geographical exploration: James and the northwest passage, 1631–33 (Calgary, 2003), which contains an extensive bibliography on the subject.

Cite This Article

Alan Cooke, “JAMES, THOMAS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 13, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/james_thomas_1E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/james_thomas_1E.html |

| Author of Article: | Alan Cooke |

| Title of Article: | JAMES, THOMAS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1966 |

| Year of revision: | 2013 |

| Access Date: | December 13, 2025 |