As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

![B.T. [Benjamin Tingley] Rogers - City of Vancouver Archives Original title: B.T. [Benjamin Tingley] Rogers - City of Vancouver Archives](/bioimages/w600.13110.jpg)

Source: Link

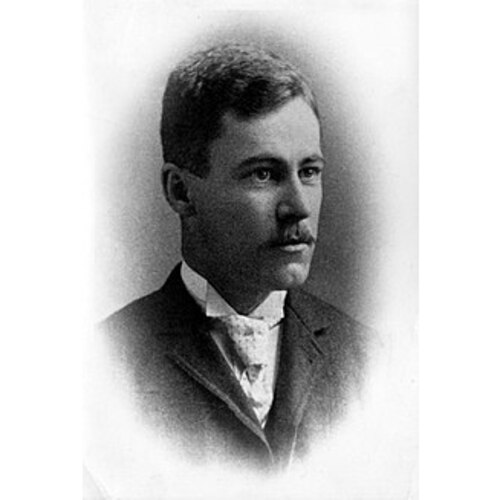

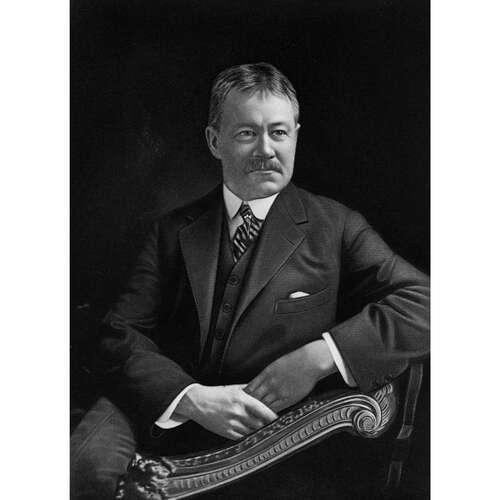

ROGERS, BENJAMIN TINGLEY, businessman; b. 21 Oct. 1865 in Philadelphia, second son of Samuel Blythe Rogers and Clara Augusta Dupuy; m. 1 June 1892 Mary Isabella Angus in Victoria, and they had four sons and three daughters; d. 17 June 1918 in Vancouver.

B. T. Rogers enjoyed a privileged upbringing and family ties to important businessmen in the American sugar industry. His father had become head of a refinery in Philadelphia, and in 1869, with his brother-in-law, Senator Henry Sanford, bought a sugar plantation in Louisiana. Samuel next established a refinery in New Orleans. After attending the prestigious Phillips Academy in Andover, Mass., Benjamin took a course in sugar chemistry at the Standard Refinery Company in Boston. When his father died in 1883, Rogers moved from New Orleans with his family and joined the Havemeyers and Elder refinery in Brooklyn (New York City), then the most modern plant in the United States. Within four years he had mastered the difficult process of sugar boiling.

Rogers aspired to organize his own business. The chance came in 1889 when he went to Montreal to install a new filtering process at George Alexander Drummond*’s Canada Sugar Refinery. While there he heard much about Vancouver, the terminus of the Canadian Pacific Railway on the west coast. Rogers saw in the city, and in the Canadian west, an untapped market for processed sugar, and he quickly took steps to establish a refinery in Vancouver. Led by the Havemeyers, New York businessmen undertook to buy shares and lend credibility to the venture. Lowell M. Palmer, a New York manufacturer of sugar barrels, arranged for Rogers to meet William Cornelius Van Horne, president of the CPR. Eager to promote its western terminus, Van Horne strongly supported Rogers’s plan and with other CPR directors – Richard Bladworth Angus*, Sir Donald Alexander Smith, Edmund Boyd Osler*, and Wilmot Deloui Matthews – bought shares in the British Columbia Sugar Refining Company. Boosters in Vancouver were equally enthusiastic. On 15 March 1890, by a vote of 174 to 8, electors approved a bylaw that granted B.C. Sugar money for a site, a tax exemption on land and improvements for 15 years, free water for 10 years, and a municipal loan. On 27 March the company was incorporated.

The politics behind the bylaw are especially interesting. In February the initiative to grant the bonus had come from John M. Browning, chair of the finance committee of Vancouver City Council and also a land commissioner for the CPR and the representative of the directors financing the refinery. Headed by a development-minded mayor, David Oppenheimer*, council did not consider Browning’s dual role to be a conflict of interest. A month after raising the bonus issue in council, Browning became B.C. Sugar’s first president.

Rogers proved to be as adept at managing the refinery as he had been at creating it. Since none of his employees had ever worked in a refinery, getting it started was a major technical challenge. With the assistance of an engineer from Havemeyers, the first melt of raw sugar was put through on 16 Jan. 1891. The depression of the 1890s started early in Vancouver, where speculation in real estate had created an unstable economy. In addition to a soft local market, Rogers faced fierce competition in Manitoba from Montreal interests and was forced to retreat from the prairies until the CPR lowered freight rates from Vancouver into the region in 1894. He also faced a challenge from Victoria when Robert Paterson Rithet and others began to sell imported Chinese sugar at below cost. It took Rogers most of the decade to win this battle. B.C. Sugar had lost money in 1891 and 1894, but it turned a profit in 1895; two years later Rogers became president. The settlement of the prairies and mining booms in the Kootenays and the Klondike stimulated demand, and, protected by a tariff from American competition, the company enjoyed a captive market in the far west. In 1899 it was reorganized: British Columbia Sugar Refinery Limited was formed as a holding company, while British Columbia Sugar Refining continued as the operating company.

Even during the depression that gripped British Columbia just before World War I, B.C. Sugar continued to grow. In 1913 Rogers’s chief chemist, Robert Boyd, whom he had recruited from the University of Toronto, developed Rogers’ Golden Syrup, a highly successful creation that used the syrupy by-product of refining. By 1916 the company’s assets had increased from an initial investment of $250,000 to $7.5 million and its daily capacity of refined sugar went from 30,000 to 900,000 pounds. Fearful of public hostility, Rogers carefully protected the resulting profits from the view of outsiders and opposed suggestions that shares in B.C. Sugar be traded on a stock exchange. He none the less had reason to say, as he did in a letter to Sir Edmund Osler in 1916, “I think . . . I am entitled to be proud of what I have been able to do.”

By Vancouver standards, Rogers became quite wealthy. Of the 25 businessmen who headed or managed the city’s largest companies prior to the war and who died before the mid 1920s, only Rogers left a fortune that exceeded $1 million. At every opportunity he had channelled his bonuses, dividends, and salary into company stock. His skill in creating and managing B.C. Sugar offers one explanation for his success. Another is his refusal to speculate in land and resources, especially urban real estate. Like other Vancouver businessmen in the late 1890s, he put money into mining companies in the Cariboo, becoming president of two of them, but thereafter his investment portfolio remained thin. In 1905 he purchased a sugar plantation in Fiji, which generated uneven profits, and a year later he bought a Vancouver hotel, Glencoe Lodge, a solid property that attracted respectable tenants. Believing that capital should be invested only for “legitimate trade purchases,” he avoided speculative investments during the city’s boom of 1909–13; after he died his estate was valued at $1,238,000.

Outspoken, brash, and “extremely self-confident,” Rogers, of all of Vancouver’s top businessmen, comes closest to meriting the label bourgeois. Business connections structured his social life. It was through his ties to the CPR that he met his future wife, Bella, a niece of CPR director R. B. Angus and his brother Forrest, B.C. Sugar’s second president. The Rogers family enjoyed a baronial lifestyle that included many servants and extensive travelling; Benjamin loved machines, especially fine automobiles and grand yachts. The children, who lived an almost separate existence from their parents, were educated in private schools in British Columbia, Ontario, and England. The Rogerses’ second house, Gabriola, the work of architect Samuel Maclure*, was the largest and finest in the city when it was completed in 1900.

While business, family, and leisure preoccupied Rogers, civic affairs did not. Like several other wealthy Vancouverites, he saw himself as part of a cosmopolitan rather than a local community. His English-born wife supported high-status charities and patronized the arts, but B.T., who retained his American citizenship for several years after moving to Vancouver, displayed little sense of civic duty. In 1897 he petitioned against a tramline to Stanley Park that would pass near his house, and in 1906 he joined the Vancouver Garden City Association, which proposed the beautification of streets in his West End neighbourhood. He did join his wife and other leading families in raising funds for a new hospital, became a life governor of the Vancouver General Hospital in 1904, and served on its board. But his name is absent from the debates on most civic issues; on one occasion, according to an obituary, he stated that “he refused to give money to public bodies because they usually squander and waste any money placed in their hands.” A Conservative, he was not politically active. He belonged to élite men’s clubs in Vancouver, Victoria, and Montreal, served as the British Columbia chairman of the Canadian Manufacturers’ Association, and was a member of the Royal Vancouver Yacht Club, of which he was commodore from 1912 to 1918. Walls of privilege enclosed the worlds of B. T. Rogers.

Upper-class attitudes also animated his relationship with labour. He believed that owners had the right to manage their businesses as they saw fit, “without reference to any union.” To keep his refinery from being “spoilt” by a union, he adopted a style of management that was both dictatorial and paternalistic. In the 1890s he sponsored the B.C. Sugar Literary and Social Club, which held annual socials for employees. In addition, in compliance with the company’s original bonus arrangement and anti-Chinese sentiments in the province, the refinery employed no Chinese workers. For 26 years such policies kept it running without a union or a strike. In 1917, however, inflation, a slow-down caused by wartime shipping disruptions, and Rogers’s refusal to authorize additional wage increases led the workforce of 206 men and 36 women to form a union. A violent, ten-week strike ensued. Attacked by the British Columbia Federationist as a “sugar lord” despised even by the “members of his own tribe of industrial despots and profit chasers,” Rogers remained uncompromising. Through detectives and strikebreakers he forced the strikers back to work on his terms, which now included some concessions on wages. That same year the company was exonerated on charges of price-fixing.

B. T. Rogers died in June 1918 of a cerebral haemorrhage and was succeeded as president by his son Blythe Dupuy. Obituaries expressed admiration for the achievements of a successful “captain of industry,” but, noticeably, they lacked any warmth of feeling for the man.

BCARS, GR 1415, file 1918/5079. B.C., Attorney General, Registrar General (Victoria), Company registration files, file 133 (1890); file 330 (1897). British Columbia Sugar Company Arch. (Vancouver), B. T. Rogers, private letter-book, 1892–1918; Share-book, 1890–93. City of Vancouver Arch., Add. mss 46 (William McNeill papers), docket no.2, John Hendry to McNeill, 15 Aug. 1910; Add. mss 54 (J. S. Matthews coll.), .03489; By-laws, vol.1, no.94: 561–68 (mfm.); City Council, minute-books, vol.3, 3 Feb., 17, 24 March 1890 (mfm.). British Columbia Federationist (Vancouver), 4–18 May, 8, 22 June, 6–13 July 1917. Daily News-Advertiser (Vancouver), 20 Jan. 1891; 27 Oct. 1892; 1 Aug. 1896; 11 May, 13 Aug. 1897; 26 July 1898: 13 Feb., 1 June 1906; 21 Jan. 1912. Vancouver Daily Province, 9 March, 21 July 1900; 28 Aug. 1902; 17 Oct. 1911; 9 March 1912; 18 June 1918. Vancouver Daily World, 12 Oct. 1901, 25 Jan. 1902, 10 May 1917, 18 June 1918. B.C. Sugar, [ed. M. I. (Angus) Rogers] ([Vancouver, 1958]). British Columbia Gazette (Victoria), 27 March 1890: 291; 11 May 1893: 376. Richard Feltoe, Redpath: the history of a sugar house (Toronto, 1991). M. I. Rogers, 1869–1965, [comp. and ed. Michael Kluckner] ([Victoria, 1987]; copy in Univ. of B.C. Library, Special Coll. and Univ. Arch. Div., Vancouver). Scholefield and Howay, British Columbia. John Schreiner, The refiners: a century of’ BC Sugar (Vancouver, 1989). Vancouver Club, Historical notes; constitution and house rules, list of members, amended to 31st May 1936 ([Vancouver, 1936], 7–11; copy in City of Vancouver Arch., Add. mss 306 (Vancouver Club fonds)). Vancouver General Hospital, Annual report, 1904: 7, 27. Vancouver social register and club directory (Vancouver), 1914 (copy in Univ. of B.C. Library, Special Coll. and Univ. Arch. Div.).

Cite This Article

Robert A. J. McDonald, “ROGERS, BENJAMIN TINGLEY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rogers_benjamin_tingley_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rogers_benjamin_tingley_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robert A. J. McDonald |

| Title of Article: | ROGERS, BENJAMIN TINGLEY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | March 29, 2025 |