Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

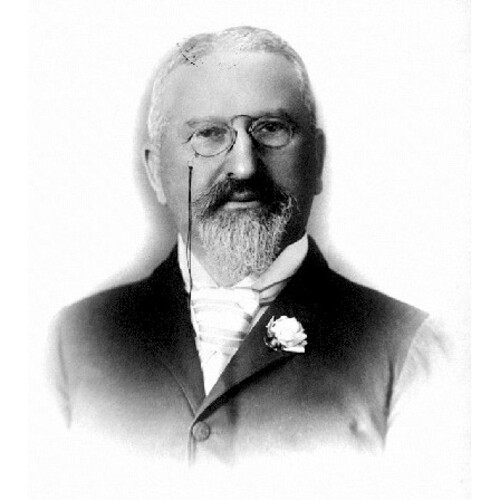

OPPENHEIMER, DAVID, businessman, politician, and author; b. 1 Jan. 1834 in Blieskastel (Federal Republic of Germany), fourth son of Salomon Oppenheimer, a merchant, and Johanetta Kahn; m. first c. 1857 Christine (Sarah) — (d. 1880); m. secondly 3 Jan. 1883, in San Francisco, Julia Walters of New York City, and they had a daughter; d. 31 Dec. 1897 in Vancouver.

David Oppenheimer was born into a Jewish family in the market town of Blieskastel. Despite certain career restrictions and religious, educational, and some residential segregation, the Jews in the town were important to the local economy as merchants and financiers, and they were fully accepted in the heterogeneous culture of the region. During the great exodus of 1848 connected with failed harvests and political turmoil, David and probably most of his ten brothers and sisters emigrated to the United States, but evidence that they left taxable property behind suggests they may have planned to return. The family first made its way to New Orleans, where David may have studied bookkeeping and worked in a general store. On 27 Feb. 1851 he and an older brother, Charles, arrived in San Francisco via Panama. By 1852 David was in Placer County, Calif., the heart of the gold-fields, working as a trader with Charles and a younger brother, Isaac. Five years later he was in Columbia, Calif., where, with his new wife and his brothers, he became active in real estate and the restaurant business. Just before the decline of the region in 1860, he probably began to cut his ties with Columbia to work in Victoria, Vancouver Island, in the supply business Charles had set up there in 1858–59.

As the gold seekers moved up the Fraser Canyon into the Cariboo district of British Columbia in 1860–61 [see William Barker], David and Isaac followed, supplying them from the Charles Oppenheimer and Company store in Yale. They expanded into wholesale business and opened new stores and warehouses in Hope, Lytton, Barkerville, and Fisherville. By the summer of 1866 they were operating their own pack-train, purchasing acreage near Lytton and in the Cariboo, and buying, developing, and selling lots in Barkerville.

Such verve was not without financial and legal risk. In October 1866, at a time of general economic decline, Charles Oppenheimer and Company was briefly put into trusteeship. Trustees were again assigned in September 1867 and David and Isaac were specifically banned from any role in managing the company, which was subsequently sold to a competitor, Carl Strouss. By March 1868 David had recouped his losses sufficiently to begin rebuilding the business from Yale while Isaac took charge in Barkerville. A disastrous fire in Barkerville that year prompted David to make one of his first civic contributions, the donation of a fire-engine. In 1871 Charles bought out Strouss and soon installed David and Isaac as partners in the newly named family firm, Oppenheimer Brothers. Around that time the importance of Barkerville began to wane, and their store there was sold in September 1872.

During the next decade Yale was the centre of the company’s operations, which were principally under David’s shrewd care. Renowned as a generous host, he became a zealous guardian of local interests. In March 1877, for example, he vigorously contested the “monopolistic” freight rates charged by Captain John Irving* on the Fraser River, and he threatened to have a consortium of Yale businessmen charter their own boats. In January 1880 he joined a syndicate with Andrew Onderdonk* to raise money for the construction of three difficult sections of the Canadian Pacific Railway near Yale. That November, despite the recent death of his wife after a long illness, Oppenheimer quickly rallied local support to protest any attempt to divert federal railway funds from the lower mainland to Vancouver Island.

Despite more than a million dollars’ worth of business with the CPR, Oppenheimer Brothers experienced cash flow difficulties, perhaps the result of granting easy credit to railway contractors. These difficulties caused the firm to adopt the cash system in March 1881. The following month creditors, among them the Hudson’s Bay Company, threatened receivership when they determined that the company had debts of more than $80,000 against assets of $187,000. Nevertheless, through persuasiveness and astute financial dealings, by mid August David had confirmed control of the company by himself and Isaac. Two weeks later fire destroyed Yale’s business section, including, despite their vaunted brick firewall, the Oppenheimers’ storey-and-a-half store and stock, together worth $170,000 but reportedly insured for only $49,000. Their imposing house was gutted, although most of its contents were saved.

Even before he began to oversee construction of a new brick store, of which the brothers never actually took possession, David was quietly loosening his ties to Yale. In mid August he offered a ranch for sale and, commuting from Victoria, was selling off company lots in Yale. As Columbia and Barkerville had faded earlier when stocks of gold dwindled, so too did Yale, in February–March 1882, at the same time as railway builders were moving into the lower Fraser valley. In January Oppenheimer Brothers had opened a large import-wholesale business on Wharf Street in Victoria. For a few years that city would prosper as the supply centre for the rest of the province but, with their customary astuteness, David and Isaac soon sensed the greater potential importance of the mainland terminus of the CPR.

Although the brothers did not move to the fledgling community of Granville (Vancouver) until late 1885 or early 1886, David had begun to acquire prime land there as early as 1878, when he persuaded several partners to join him in buying 300 acres on Burrard Inlet. In the summer of 1884 he and other Victoria capitalists bought more land at Coal Harbour and English Bay, lobbied the provincial government to assist the CPR in extending its line westward from Port Moody, and encouraged other landowners to join them in donating about 175 acres to the railway. After the CPR officially announced the extension of its line to Granville, Oppenheimer continued, at least until 1886, to buy more land at government auction. At the beginning of 1887 the assessed value the Oppenheimer Brothers’ holdings, through their Vancouver Improvement Company, was $125,000, the largest after the CPR ($1,000,000) and the Hastings Saw Mill ($250,000).

Oppenheimer Brothers opened the first wholesale grocery house in Vancouver in July 1887, but David concentrated on promoting the development of the city. He urged city council to assist new enterprises, advertised investment opportunities in Vancouver and throughout the province, participated in civic politics, and invested personally in various developmental schemes in the city and in the Fraser valley. These activities, which enhanced the value of his own real estate holdings, were so intertwined that it is frequently impossible to separate his interests as a municipal politician and as an investor and entrepreneur.

Once settled in Vancouver, Oppenheimer had become involved in public affairs. He was one of the “inhabitants of Granville” who petitioned the provincial legislature for the incorporation of the city [see Malcolm Alexander MacLean]. After incorporation, on 6 April 1886, city council met in Oppenheimer’s office until the city hall, built on land he donated, was completed. In the second municipal election, held in December 1886, David and Isaac were acclaimed aldermen for Ward 4, a sparsely settled area on the east side of Vancouver where most of their land was located. As chairman of the finance committee, David earned an excellent reputation for putting the city’s financial affairs in good order. In December 1887 he was acclaimed mayor.

In line with his program of building up commerce, improving civic amenities, exploiting provincial resources, and encouraging the development of suitable industries, Oppenheimer had joined a group of businessmen who were organizing the Vancouver Board of Trade, and in November 1887 he was elected the first president. He also worked personally to draw attention to local industrial opportunities. This task often consisted in boosting the city through such activities as a celebration on the arrival of the Empress of India, the first of the CPR’s new transpacific liners, and sending samples of provincial products to eastern Canadian exhibitions. In 1889 he prepared a pamphlet, The mineral resources of British Columbia: practical hints for capitalists and intending settlers, which was distributed in London and the United States. He went to Europe seeking investors for a blast-furnace, a rolling-mill, and a sugar-beet refinery, and he encouraged the city to offer subsidies either as cash bonuses or as tax concessions to a variety of enterprises, including a dry dock, a smelter, and a sugar-cane refinery. Although the first two failed, mainly through lack of other financial assistance, the British Columbia Sugar Refinery was a marked success.

With city council Oppenheimer spent much time setting up basic services, such as a fire department and water supply, and constructing streets, sidewalks, and sewers. He was proud of his success in selling city bonds in London to pay for such projects. His critics, however, alleged with some reason that his public works projects were “utterly utopian” and tended to scatter the population.

Oppenheimer was deeply involved with the promotion of public utilities. As mayor he successfully advocated municipal ownership of such concerns as the Vancouver Water Works Company, and he often put his own capital and energy into enterprises such as a public wharf, which he hoped the city would eventually purchase. Most significant were his investments in electrical utilities. He was an early shareholder of the Vancouver Electric Illuminating Company (founded in 1886), which secured the contract to light city streets. The Oppenheimer brothers also invested in its successor, the Vancouver Electric Railway and Light Company (formed in 1890), whose street railway lines operated near their real estate holdings on both the east and the west sides of the city. Always active in this corporation, David became a major shareholder only after he retired from the mayor’s office in 1891. Even while mayor, however, he was a principal promoter of the Westminster and Vancouver Tramway, a 13-mile electric railway which passed through an area of east Vancouver where the Oppenheimers had extensive holdings suitable for residential lots. Although his estate eventually received $50,000 for his interest in the tramway, David probably lost his direct investment in his other electrical utility ventures without gaining much immediate benefit because of a dull real estate market.

David Oppenheimer’s involvement in these enterprises, notably the tramway, which required the city to open and grade new streets, led political enemies to complain of “boodling.” No one challenged him when in 1888 he ran for a second term as mayor but by the fall of 1889 his popularity was waning. William Templeton, a grocer, accused Oppenheimer of conflict of interest and criticized him for spending too much time building “castles in the air” and not enough on civic administration and law enforcement. Templeton secured 434 votes to Oppenheimer’s 585. The next year Gilbert S. McConnell, a weak candidate, contested the mayor’s seat but gained only 184 of the 960 votes cast. Significantly, more than 300 of those who voted for aldermen did not cast a ballot for mayor. This led the Vancouver Daily News-Advertiser, the champion of the anti-Oppenheimer forces, to suggest that a strong candidate could easily have defeated him. More important, a majority of the aldermen opposed Oppenheimer, who led the city’s east side interests.

The mayor undoubtedly realized his vulnerability. During 1891 council was deadlocked for several months over the dismissal of the city engineer and the appointment of a successor. After Oppenheimer and all but one of the aldermen proposed to resign, the council agreed to name the compromise candidate favoured by the mayor. This short term “signal victory” added to a popular sense that, in the words of the Daily News-Advertiser, Oppenheimer was “blinded by vanity and an overwhelming sense of his own importance.” That December, despite a published request from some 400 residents, including many prominent businessmen, Oppenheimer, who was confined to his hotel room by illness, pleaded health and business concerns and declined to seek a fifth term.

After retiring from active political life, Oppenheimer concentrated on managing his investments, especially on trying to sell the financially troubled Vancouver Electric Railway and Light Company to the city and on refinancing the tramway. In June 1893, however, trustees for the debenture holders took over the railway and in August 1894 the tramway went into receivership.

When Oppenheimer died in 1897 his fortune was in such serious decline and his estate so complex that the provincial finance minister, John Herbert Turner*, accepted the trustees’ estimate of $20,000 as fair value for the entire estate. That conservative estimate in the short run was not unreasonable. The Vancouver Improvement Company was valued at $303,058 but had an overdue mortgage against it. Similarly, Oppenheimer Brothers held 44.8 per cent of the stock of the British Columbia Drainage and Dyking Company, but a flood in 1894 had made its Pitt River lands unattractive. Even the grocery company had suffered an erosion of capital, although it was subsequently reorganized by David’s nephews and continues to operate in Vancouver.

Oppenheimer had suffered years of indifferent health, and his death, no doubt hastened by the tragic loss of his second wife, who had fallen off a train, was not totally unexpected. He lay in state at the masonic temple in Vancouver, where services were conducted, and he was buried beside his second wife in a Jewish cemetery in Brooklyn, N.Y.

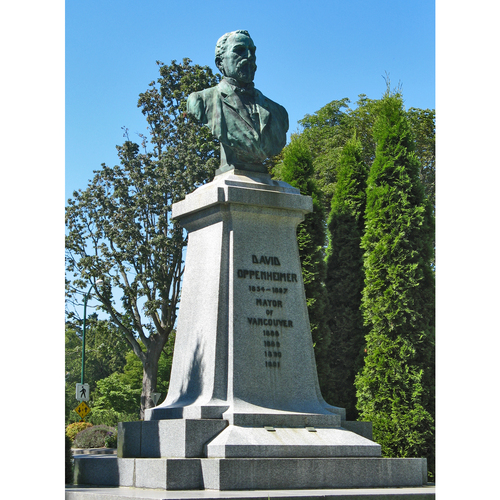

As mayor, Oppenheimer had had many enemies, but his obituaries were uniformly friendly and full of praise for his love of Vancouver and his generosity as an official host to visitors and as a benefactor to such charities as the Young Men’s Christian Association and the Alexandra Orphanage. These tributes were not mere sentimentalities of the moment. In 1911 his friends, through funds raised by public subscription, erected a monument to him at the Beach Avenue entrance to Stanley Park. At the time of the unveiling, the once hostile Vancouver Daily News-Advertiser reprinted its 1898 description of him as “the best friend Vancouver ever had.”

[The City of Vancouver Arch. has a small collection of Oppenheimer family papers (Add. mss 108); the most interesting material in it, the records of probate for Oppenheimer’s estate, is largely duplicated in PABC, GR 1415, P216. Much of the remaining material in the Oppenheimer papers has been copied in a typescript miscellany, “His Worship Mayor David Oppenheimer; mayor of Vancouver, 1888, 1889, 1890, 1891,” comp. J. S. Matthews (Vancouver, 1934), available in the library of the City of Vancouver Arch. It includes contemporary newspaper articles eulogizing Oppenheimer and telegrams and invitations, mainly of a social nature. The civic archives holds extensive records of the early municipal governments, notably in the correspondence of the City Clerk’s Dept.

Some business records of the early electrical utility companies in which Oppenheimer invested have also survived and are included in the British Columbia Electric Railway Company Ltd. records at the Univ. of B.C. Library, Special Coll. (Vancouver), M75. Information on Oppenheimer’s land purchases in Vancouver can be gleaned from a variety of materials in the PABC, notably B.C., Dept. of Lands and Works, vol.138; GR 824, 5; the diaries of Edgar Crow Baker (Add. mss 707); and the correspondence of Dr I. W. Powell (GR 1372, F 1445). In addition, the three publications compiled or written by Oppenheimer himself suggest some of his promotional activities: Vancouver City, its progress and industries, with practical hints for capitalists and intending settlers (1884), Vancouver, its progress and industries . . . (1888), and The mineral resources of British Columbia: practical hints for capitalists and intending settlers . . . (1889), all published in Vancouver.

Most contemporary information on the years in Yale, Barkerville, and Victoria is contained in the following newspapers: British Columbia Tribune (Yale), 10 April 1865–8 Oct. 1866; British Columbia Examiner (New Westminster; Yale), 9 Nov. 1866–28 Dec. 1868; Inland Sentinel (Emory, B.C.; Yale), 1880–84; Cariboo Sentinel (Barkerville), 6 June 1865–30 Oct. 1875; and the Victoria British Colonist, 1858–60, and Daily British Colonist, July 1860–October 1880. Similarly, Oppenheimer’s Vancouver career is well documented in the friendly Vancouver Daily World, 1888–98, esp. 31 Jan. 1892, and Daily Herald, July 1887–June 1888, and in the frequently critical Daily News-Advertiser, 1866–98, esp. 1 Jan., 2 June 1891, 5 Jan. 1892; 14 Dec. 1911.

Authoritative secondary sources on Oppenheimer are few: Gutkin, Journey into our heritage: the story of the Jewish people in the Canadian west (Toronto, 1980), for instance, is not consistently reliable. Two articles on early Vancouver, however, do provide valuable information on Oppenheimer and the milieu in which he operated as a businessman and local politician: Norbert Macdonald, “The Canadian Pacific Railway and Vancouver’s development to 1900,” BC Studies, no.35 (autumn 1977): 3–35; and R. A. J. McDonald, “The business elite and municipal politics in Vancouver, 1886–1914,” Urban Hist. Rev. (Ottawa), 11 (1982–83), no.3: 1–14. p.l. and p.e.r.]

American Jewish Arch. (Cincinnati, Ohio), Oppenheimer family tree, comp. W. S. Hilborn (Los Angeles, 1974). Landesarchiv Saarbrücken (Saarbrücken, Federal Republic of Germany), Index zum Inventar der Quellen der jüdischen Bevölkerung in Rheinland-Pfalz and Saarland von 1800/1815–1945, Bd.20, Akten 2035–38, 2045, 2053, 2055; Municipal records of Blieskastel. PABC, GR 216, 195; GR 833. Stadtamt Blieskastel (Blieskastel, Federal Republic of Germany), Docs. recording first Jewish presence (1690s) and first appearance of name Oppenheimer (1720s) in Blieskastel; first registration of Jews, 1808; David Oppenheimer, birth certificate, 1834; Oppenheimer family vital statistics. Colonial farm settlers on the mainland of British Columbia, 1858–1871 . . . , comp. F. W. Laing (Victoria, 1939).

Cite This Article

Peter Liddell and Patricia E. Roy, “OPPENHEIMER, DAVID,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/oppenheimer_david_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/oppenheimer_david_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Peter Liddell and Patricia E. Roy |

| Title of Article: | OPPENHEIMER, DAVID |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |