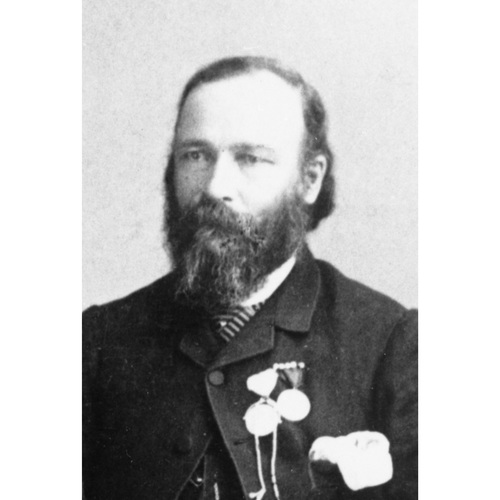

![Jean L'Heureux. [ca. middle 1880s]. Image courtesy of Glenbow Museum, Calgary, Alberta. Original title: Jean L'Heureux. [ca. middle 1880s]. Image courtesy of Glenbow Museum, Calgary, Alberta.](/bioimages/w600.11512.jpg)

Source: Link

L’HEUREUX, JEAN, interpreter; b. c. 1837 in Lower Canada; d. 19 March 1919 in Midnapore, Alta.

Historians once said that Jean L’Heureux was born in L’Acadie, Lower Canada, but this claim proved to be an error. There are sources stating his birthplace was in France, at Trois-Rivières, near Saint-Hyacinthe, and at Longueuil. L’Heureux himself commented that his mother was buried “only a few miles” from Montreal. Similarly he is alleged to have attended the seminary in Montreal, Saint-Hyacinthe, or Trois-Rivières, but none has a record of him. However, he was obviously well educated and, according to recollections of Oblate priests, he had studied for the priesthood but was expelled because he was either caught as a thief or exposed as a homosexual.

An early mention of L’Heureux in western Canada appears in a letter from Father Albert Lacombe to Bishop Alexandre-Antonin Taché* in 1861 when he refers to the “famous L’Heureux.” Correspondence indicates that L’Heureux wanted to work for the Oblate order. During that summer he stayed at St Albert mission, just north of Fort Edmonton (Edmonton), but was caught in the act of sodomy. The priests arranged for him to join a band of Blackfoot who had come to trade and he travelled with them to Montana. During this time he donned a cassock and told the Indians he was a priest labouring for the Oblates. In Montana he passed himself off to the Jesuits as a secular priest. In the spring of 1862, according to a letter written to Methodist missionary Thomas Woolsey by a Stoney Indian, L’Heureux saved some Stoney from starving to death and from being killed by Blood Indians. The Stoney praised him and identified him as “the priest at the Chief Mountain.” In the summer L’Heureux returned to St Albert indicating he had built a church for the Jesuits at Chief Mountain, on the present Alberta–Montana boundary. “It appears,” wrote Father Lacombe, “that he has deceived the Jesuit fathers even better than he has me.”

Later that summer L’Heureux sent a package of gold-bearing sand to a trader in Fort Benton, Mont., stating that he could guide prospectors to the gulch where it had been found. A party of 11 men immediately set out and travelled north almost to Fort Edmonton without finding either L’Heureux or gold. Some were convinced that he had deliberately victimized them while others believed he had changed his mind, fearing an influx of whites into Indian lands.

Over the next several years L’Heureux lived with the Blackfoot, often wearing a cassock and performing baptisms and marriages. He was despised and vilified by the clergy and fur traders both for being homosexual and for pretending to be a priest. He was also mistrusted because of his complete devotion to the Indians who, he had discovered, did not condemn homosexuality. He took the Blackfoot name of Nio’kskatapi, or Three Persons, after the Holy Trinity.

Although he was anathema to the Catholic clergy and the Hudson’s Bay Company, both made use of him. The traders supplied him with goods and arranged for him to bring the Blackfoot in to trade; the priests used him as a guide and interpreter. Also, in 1865 the latter provided him with a baptismal register and permitted him to act as a participant when a priest administered sacraments among the Blackfoot.

L’Heureux’s first concern appeared to be the Indians. In 1865 he brought Father Lacombe to a Blackfoot camp during a measles epidemic. When Lacombe fell victim to the disease, according to Father Paul-Émile Breton, “L’Heureux took excellent care of the young priest and succeeded in saving his life.” L’Heureux then rode to Fort Edmonton to report the epidemic and to beg for medicines to help the Indians. In 1869 he wrote to the Sisters of Charity of the Hôpital Général of Montreal at St Albert, describing the symptoms of a Stoney woman who was subject to fits and seeking their advice and prayers. In 1879 he begged the North-West Mounted Police at Fort Calgary (Calgary) to send food to the Blackfoot who were starving. And in 1883 he travelled in mid winter to report a typhoid epidemic among the Blackfoot and to request medicine for them.

Because he was such an embarrassment to the Oblates, they seldom mentioned him in their historical accounts. For example, one of the most colourful events of Father Lacombe’s career occurred in 1865 when he was in a Blackfoot camp which was attacked by Cree. Lacombe rushed out of a lodge and tried to stop the fighting but was wounded by a spent bullet. Although the battle was told and retold in Catholic literature, including an account by Lacombe, no reference was made to the fact that L’Heureux was by the priest’s side during the entire incident. Only in interviews with Indians is this fact revealed.

In 1869 the American army killed a large number of Peigan Indians in an attack on the Marias River, Mont. This massacre came at the culmination of a series of incidents between tribes of the Blackfoot confederacy and Montanans. Many Peigan and Blood fled across the border into Canada for the winter and, fearing to return, they sent L’Heureux as their peace emissary. He drafted a letter to Brigadier-General Alfred Sully, dictated by the chiefs, which stated that “the Three-Persons [L’Heureux] will go to your lodge. He will give news to you that our will is all good. . . . We pray for peace with your white children.” The letter was forwarded to Washington and, as a result, better relations were restored.

L’Heureux’s literary talents were exhibited on a number of occasions. In 1871 he prepared a manuscript, “Description of a portion of the Nor-West and the Indians.” In 1873 he did a map and census of Blackfoot territory for the HBC trader at Rocky Mountain House (Alta). Acting on behalf of the chiefs of the Blackfoot, Blood, and Peigan, in 1876 he drafted a “Petition of . . . chiefs of the Chokitapia or Blackfeet Indians of North West Territory.” In 1878 he compiled an English-Blackfoot dictionary for a trader at Fort Calgary, and in 1884 he wrote “Ethnological notes on the astronomical customs and religious ideas of the Chokitapia or Blackfeet Indians, Canada.” The latter was prepared for submission to the British Association for the Advancement of Science.

Our Lady of Peace mission was built near the future site of Calgary in 1873, and L’Heureux spent the winter of 1874–75 there as interpreter and assistant to the resident priest, Constantine Michael Scollen. The following year he brought Blackfoot chief Old Sun [Natos-api*] and his band to the mission.

In 1877, when Treaty No.7 was negotiated between the Blackfoot tribes and the Canadian government, Lieutenant Governor David Laird tried to engage L’Heureux as his interpreter. But L’Heureux indicated that he would be interpreting for Crowfoot [Isapo-muxika*] and the other chiefs. However, he did provide the commissioners with a list of chiefs and bands. Frank Oliver*, who attended the event, commented, “He stood unswervingly with the Indians as an Indian.” L’Heureux also inscribed the Blackfoot names on the treaty document and signed as a witness.

L’Heureux accompanied the Blackfoot into Montana in pursuit of the diminished herds of buffalo in 1879. While there, he was approached by Louis Riel*, who wanted his help in seizing the Canadian west in order to create a special territory for the Indian and Métis people. L’Heureux informed the authorities, and when members of the tribe went to Fort Walsh (Sask.) that autumn to collect their treaty money, he was hired by the Indian affairs branch as an interpreter. The Blackfoot returned to Canada in 1881 to settle on their reserve east of Fort Calgary. He stayed with them and was an employee of the Department of Indian Affairs for the next ten years. He accompanied the chiefs on a trip to Regina in 1884 to meet Lieutenant Governor Edgar Dewdney, remained with the Blackfoot and counselled peace during the uneasy period of the North-West rebellion, and in 1886 was the interpreter for the “loyal” chiefs (Crowfoot, Red Crow [Mékaisto*], and others) during a trip to Montreal and Ottawa.

L’Heureux was dismissed by the department in 1891 after an Anglican missionary accused him of showing favouritism to the Roman Catholic Church. An investigation showed that he had been giving religious instruction to pre-school Blackfoot children to assure their admittance into the Catholic mission. L’Heureux moved to Father Lacombe’s hermitage at Pincher Creek and then retreated into the foothills where he became a virtual recluse. In 1912 he was admitted to the Lacombe Home in Midnapore, still wearing his cassock and clerical collar. He died there in 1919 and was listed in the church records as a “lay missionary.”

Jean L’Heureux’s 1871 “Description of a portion of the Nor-West and the Indians” is preserved in NA, MG 29, C33. The 1876 petition is in PAM, MG 12, B1, no.1265, and the manuscript English-Blackfoot dictionary is in GA, M4418, D970.3/T586. L’Heureux’s 1884 paper on the Blackfoot was published in Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Journal (London), 15 (1886): 301–4.

Arch. de l’Archevêché de Saint-Boniface, Man., T 1611–14 (Fonds Taché, lettre d’Albert Lacombe, 30 août 1862). NA, RG 10, 3766, file 32864. PAA, Arch. of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, Prov. of Alberta-Saskatchewan, 71.220, item 6532. Ben Bennett, Death, too, for The-Heavy-Runner (Missoula, Mont., 1982). P.-É. Breton, The big chief of the prairies: the life of Father Lacombe, trans. H. A. Dempsey (Montreal, 1956). P. H. Godsell, “The Lost Lemon mine,” Wide World Magazine (London), August 1948: 281–84. R.[-J.-A.] Huel, “Jean L’Heureux: Canadien errant et prétendu missionnaire auprès des Pieds-Noirs,” in Après dix ans . . . bilan et prospective, sous la direction de Gratien Allaire et al. (Edmonton, 1992), 207–22. J. [C.] McDougall, George Millward McDougall, the pioneer, patriot and missionary (Toronto, 1888). Alexander Morris, The treaties of Canada with the Indians of Manitoba and the North-West Territories . . . (Toronto, 1880; repr. 1971). Frank Oliver, “The Blackfeet Indian treaty,” Maclean’s (Toronto), 44 (1931), no.6: 8–9, 28, 32, 56. [Patrick] Robertson-Ross, “Robertson-Ross’ diary, Fort Edmonton to Wildhorse, B.C., 1872,” ed. H. A. Dempsey, Alberta Hist. Rev. (Calgary), 9 (1961), no.3: 5–22. Thomas Woolsey, Heaven is near the Rocky Mountains: the journals and letters of Thomas Woolsey, 1855–1869, ed. H. A. Dempsey (Calgary, 1989).

Cite This Article

Hugh A. Dempsey, “L’HEUREUX, JEAN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 2, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/l_heureux_jean_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/l_heureux_jean_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Hugh A. Dempsey |

| Title of Article: | L’HEUREUX, JEAN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | April 2, 2025 |