Source: Link

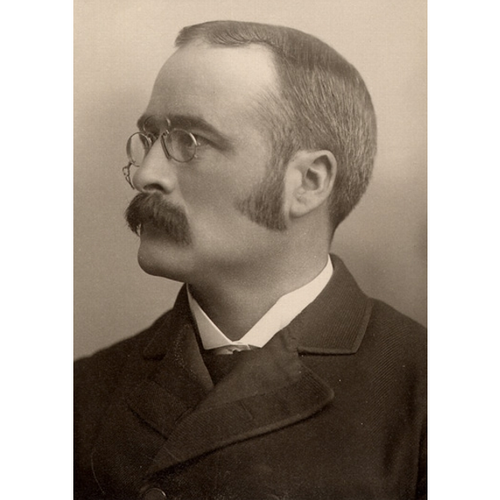

CANNON, LAWRENCE JOHN, lawyer, office holder, and judge; b. 18 Nov. 1852 at Quebec, son of Lawrence Ambrose Cannon, a lawyer and city clerk at Quebec, and Mary Jane Cary; m. 2 Aug. 1876 Marie-Hermine-Aurélie-Alida Dumoulin, daughter of Jean-Gaspard Dumoulin* and Alida Pacaud, in Saint-Christophe-d’Arthabaska, Que., and they had eight children; d. 30 Jan. 1921 at Quebec.

The great-grandson of Edward Cannon*, an Irishman who settled at Quebec in 1795 and worked there as a master mason with his son John*, Lawrence John Cannon belonged to one of the city’s prominent families. At his baptism, his godfather was Augustin-Norbert Morin*, who was then co-premier of the Province of Canada with Francis Hincks*. Lawrence John did his classical studies at the Séminaire de Québec (1862–70) and the Séminaire de Nicolet (1870–71), and then enrolled at the Université Laval, where he obtained a degree in law in June 1874. Called to the bar in July, he practised for a few months at Quebec before moving in 1875 to Arthabaskaville (Victoriaville), where he went into partnership with Édouard-Louis Pacaud*. He soon became part of the little circle of friends which included the Pacaud brothers, Wilfrid Laurier*, Marc-Aurèle Plamondon*, and Joseph Lavergne. As the Liberal candidate for the riding of Drummond and Arthabaska in the federal election of 20 June 1882, Cannon was defeated by the Conservative incumbent, Désiré-Olivier Bourbeau. When the Temperance League of the County of Arthabaska was founded in 1885, he was a member of the first board of directors, along with Laurier and others. On 2 Feb. 1891 the government of Honoré Mercier* appointed him deputy attorney general and law clerk for the province of Quebec, an office he retained under successive Conservative and Liberal administrations until 1905. On 29 July of that year he became a judge of the Superior Court for the district of Trois-Rivières.

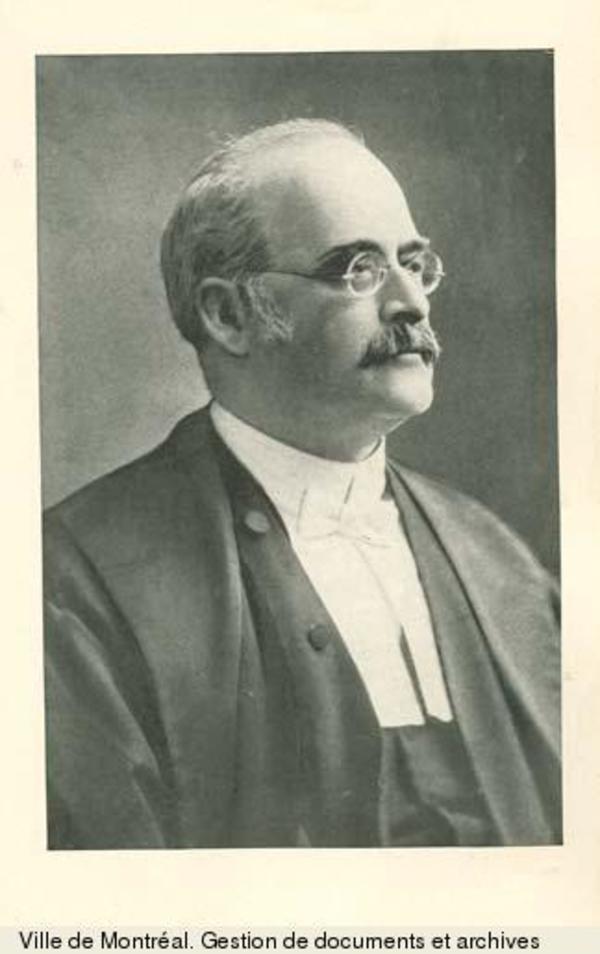

The most important event in Cannon’s judicial career was his appointment on 7 April 1909 by the government of Sir Lomer Gouin as a one-man royal commission to make a general and complete inquiry into the administration of the affairs of the city of Montreal. This commission, which would also be known as the Cannon inquiry, was set up in response to pressure from a committee of citizens which, among others, included former mayor Hormisdas Laporte*, notary Victor Morin, and Senator Raoul Dandurand*. In view of the inefficient management by the committees of the city council, these citizens called for reforms in the municipal administration and especially for the creation of a board of control having the executive power. With the assistance of a secretary, lawyer Arthur Gagné, Cannon commenced his work on 19 April but adjourned it until 27 April, the date on which the inquiry really began. He held 115 sessions and heard 914 depositions, in the course of which 548 pieces of evidence were produced. His mandate required him to submit a report before 15 July, but the hearings, at which the lawyers for the citizens’ committee, Joseph-Léonide Perron and Napoléon-Kemner Laflamme, acted as prosecutors, did not conclude until 14 September.

Reported in detail by the Montreal press, the hearings showed that there had been corruption and patronage in the innermost reaches of the city’s administration. On 20 September, before Cannon had submitted his report, the provincial government held a referendum on the amendments it had made to the city’s charter under a statute enacted in May 1909. These amendments reduced the number of aldermen per ward and created the board of commissioners, a board of control consisting of the mayor and four members elected for four years. A third of the citizens of Montreal took part in the referendum; 88 per cent voted in favour of creating a board and 92 per cent for reducing the number of aldermen from two to one per ward.

On 13 Dec. 1909 Cannon finished writing his report. He made it clear from the outset that the evidence presented to him enabled him to “form an accurate idea of the existing abuses and irregularities in the civic administration of Montreal.” Following the course of the inquiry, he dealt first with the organization and operation of the police. He concluded that there was systemic tolerance with regard to houses of prostitution, gaming houses, and the sale of alcohol on Sunday, that appointments and promotions required payments, and that the chief of police was sometimes “a too subservient instrument in the hands of certain aldermen.” He recommended that the police commission, composed of aldermen who supervised the police department, be abolished, and that the number of police officers be increased. Turning to the fire department, the judge again attacked a jobs-for-sale system controlled by go-betweens, aldermen, and officers of the fire brigade [see Zéphirin Benoit]. His comment on the situation was unequivocal: “It is hard to imagine a more wretched occupation.” The evidence concerning the roads department led him to the conclusion that it had to be entirely reorganized if it was to become economical, efficient, and honest. He recommended the abolition of the roads commission which supervised the department.

When he made these recommendations, Cannon knew that the voters had approved the board of commissioners, which marked the end of commissions made up of aldermen. He noted that this new authority “will have to find a solution to current abuses.” Evidence of corruption and patronage involving other authorities was mentioned by the judge. For example, he was led to describe the city’s decision to drop charges against dairymen who supplied products of inferior quality as “quasi-criminal interference from the aldermen,” because, in his view, it endangered the health of the population. On the completion of his general inquiry, Cannon concluded that “the administration of the affairs of the City of Montreal by its Council since 1902 has been saturated with corruption arising mainly from the scourge of patronage” and that reduction of the number of aldermen and creation of a board of control would improve municipal administration. His recommendations concerning the creation of a “council composed of aldermen, representing the whole city,” as well as prosecution and fines for the individuals named by the inquiry, would not be acted on. In February 1910 the candidates backed by the citizens’ committee took control of the city council. All the aldermen incriminated by the report either were defeated or did not stand for re-election. The board of commissioners would be retained until 1918.

On 6 July 1910 judge Lawrence John Cannon was transferred to the Quebec district, where he served until his death in 1921. The daily Le Soleil referred to him at this time as “that brilliant magistrate whose worthy and honourable career had won him the esteem and respect of all,” and it mentioned that his report on the administration of Montreal “is still famous both for the facts brought to light and for the conclusions of the learned judge.” Two of Cannon’s sons would also be appointed to the bench: Lawrence Arthur Dumoulin*, judge of the Court of King’s Bench and of the Supreme Court of Canada, and Lucien, judge of the Superior Court for the district of Quebec.

Lawrence John Cannon is the author of Rapport sur l’administration de la ville de Montréal, décembre 1909 (s.l., n.d.) and, with François Laroche, of Tariffs of officers of justice and registrars in the province of Quebec, with supplement and index (Quebec, 1902), also published in French.

ANQ-MBF, CE402-S2, 2 août 1876. ANQ-Q, CE301-S1, 18 nov. 1852. VM-DGDA, P39; VM6, Dossiers de coupures de presse, D010.9: enquête-commission Cannon-année 1909. Le Soleil, 31 janv., 1er févr. 1921. J.-P. Brodeur, La délinquance de l’ordre: recherches sur les commissions d’enquête (1v. paru, La Salle, Qué., 1984– ), 55–71. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). I.-J. Deslauriers, La Cour supérieure du Québec et ses juges, 1849–1er janvier 1980 (Québec, 1980), 166. “Les disparus,” BRH, 33 (1927): 210. Michel Gauvin, “The reformer and the machine: Montreal civic politics from Raymond Préfontaine to Médéric Martin,” Journal of Canadian Studies (Peterborough, Ont.), 13 (1978–79), no.2: 20–21. Linteau, Hist. de Montréal, 258–60. C.-V. Marsolais et al., Histoire des maires de Montréal (Montréal, 1993), 198–204. Que., Statutes, 1885, c.54. P.-G. Roy, Les juges de la prov. de Québec, 90–91. Rumilly, Hist. de Montréal, 3: 397–412.

Cite This Article

Mario Robert, “CANNON, LAWRENCE JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 4, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cannon_lawrence_john_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cannon_lawrence_john_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Mario Robert |

| Title of Article: | CANNON, LAWRENCE JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2013 |

| Access Date: | April 4, 2025 |