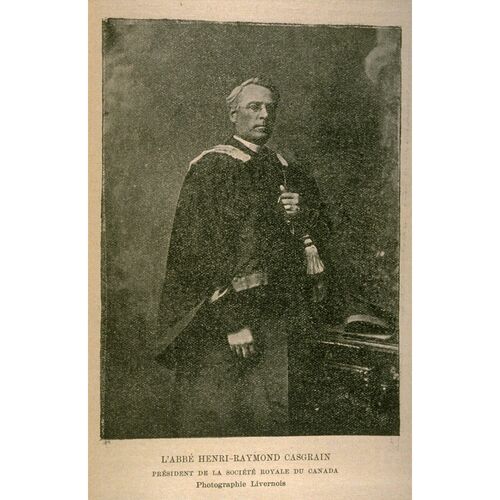

CASGRAIN, HENRI-RAYMOND, Roman Catholic priest, author, publisher, and historian; b. 16 Dec. 1831 in Rivière-Ouelle, Lower Canada, fifth of the 14 children of Charles-Eusèbe Casgrain* and Eliza Anne Baby; d. 11 Feb. 1904 at Quebec.

By the time Henri-Raymond Casgrain entered the Collège de Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière on 23 Feb. 1843, he had acquired from his mother a love of study and reading. At the college Abbé Jean-Cléophas Cloutier interested him in Canadian history, and Abbé Pierre-Henri Bouchy introduced him to French literature. He stood first in Rhetoric, the sixth year of the classical college program, and was “one of the most talented in his class, especially in Philosophy.” He enrolled in the Montreal School of Medicine and Surgery in the fall of 1852, but soon realized he was not suited to the medical profession.

On 2 Feb. 1853 Casgrain began his studies in theology at the Grand Séminaire de Québec, but he contracted bronchitis in the spring of 1854 and returned home for several months. Archbishop Pierre-Flavien Turgeon* of Quebec allowed him to take theology at the Collège de Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière, where he also taught literature, catechism, and drawing. On 5 Oct. 1856, at the college, Casgrain was ordained to the priesthood. Three years later, however, he was forced to give up teaching because of ill health. He was appointed curate of the parish of La Nativité-de-Notre-Dame at Beauport in 1859.

Casgrain began to devote himself to literature at this time. In 1860 he published two French Canadian legends in Le Courrier du Canada under the pseudonym of Mme E. B., his mother’s initials. The first, “Le tableau de la Rivière-Ouelle,” was written as a tribute to the poet Octave Crémazie* and the second, “Les pionniers canadiens,” was dedicated to the historian François-Xavier Garneau*. He wished to win the favour of these two men and thereby gain readier access to Quebec literary circles, where they both were key figures. His appointment on 5 May 1860 as curate of Notre-Dame de Québec permitted the fulfilment of his hopes, for he could now frequent Crémazie’s bookstore, the meeting-place that drew Garneau, Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Ferland*, François-Alexandre-Hubert La Rue*, Joseph-Charles Taché*, Étienne Parent*, Antoine Gérin-Lajoie*, Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau*, and the young poets Alfred Garneau, Louis Fréchette, and Pamphile Le May*. With the publication in September 1860 of a third legend, “Le Saint-Laurent, fantaisie,” written to honour Taché, Casgrain thought he would be accepted into this circle of writers.

The literary movement then taking shape gave rise to two magazines published at Quebec, Les Soirées canadiennes and Le Foyer canadien, both of which contributed to the flowering of French Canadian letters. As a founder of Les Soirées canadiennes, the enthusiastic Casgrain kept the magazine running smoothly; he acquired articles, corrected proofs, and encouraged writers to retell Canadian legends in prose or poetry. He himself published a fourth one, “La jongleuse,” in 1861.

Following a dispute with the publishers Jean-Docile and Léger* Brousseau, Casgrain and four other members of Les Soirées canadiennes left and became publishers and proprietors of Le Foyer canadien in 1863. Casgrain devoted his energies to it. He corrected the proofs of Philippe-Joseph Aubert* de Gaspé’s novel Les anciens Canadiens and prepared the volume issued as a premium in 1864, the second volume of La littérature canadienne de 1850 à 1860, which contained the poems of Crémazie previously published in periodicals and Philippe-Ignace-François Aubert de Gaspé’s novel “Le chercheur de trésors ou l’influence d’un livre.”

Buoyed by the prestige he had come to enjoy over the years, Casgrain felt ready to spell out new directions for literary endeavours in an essay that he published in Le Foyer canadien in 1866, entitled “Le mouvement littéraire en Canada.” He was not as innovative as he thought, however, for many of his ideas had long since been advanced by other writers. But he does deserve credit for synthesizing the patriotic aspirations of French Canadian intellectuals. His recommendations were followed for many years by writers who saw in this manifesto the guidelines for a national literature oriented towards patriotism and religion.

Casgrain was already quite well known. In particular, he had to his credit a collection entitled Légendes canadiennes (Québec, 1861); a historical work, Histoire de la mère Marie de l’Incarnation . . . (Québec, 1864); and a number of biographies of his contemporaries: Antoine-Sébastien Falardeau* (1862), Auguste-Eugène Aubry (1865), François-Xavier Garneau (1866), Jules-Isaïe Benoît*, dit Livernois (1866), and Georges-Barthélemi Faribault* (1867). Apart from his literary activities, during the years 1865–68 he also discreetly supported the group in Canada that drew its inspiration from French theologian Jean-Joseph Gaume [see Alexis Pelletier].

Although all his life he was troubled by an eye ailment, Casgrain remained full of energy. His collection of poems, Les miettes: distractions poétiques ([Québec], 1869), a work he dedicated to his friend Antoine Gérin-Lajoie, was brought out after a two-year illness. In the next years he published biographies of Philippe-Joseph Aubert de Gaspé (1871) and the American historian Francis Parkman* (1872), as well as caricatures of his own contemporaries in L’Opinion publique (1872) which appeared under the pseudonym of Placide Lépine. He formulated his ideas on literary criticism in Critique littéraire (Québec, 1872), putting forward analytical criteria for a “sound and vigorous” approach.

In September 1872 Casgrain left the ministry permanently on account of his health and went back to Rivière-Ouelle for a few years. The superintendent of the Department of Public Instruction, Gédéon Ouimet, invited him in 1876 to identify “a series of Canadian books for school prizes.” His task was to select the authors and the volumes that best represented the tastes of the Canadian public. Casgrain became the intermediary between the department and the printer. The agreement established a list of Canadian works to be given as prizes, the number to be supplied to the government, and the costs for which the printer and binder were to be paid. Over a ten-year period the department bought some 80,000 volumes. Casgrain sold them to the government for more than they cost him, and after the printers, Léger Brousseau and Augustin Côté, and the binder had been paid, he realized substantial profits of more than $1,000 a year. In return for a life annuity at six to eight per cent, he gave these sums to various religious communities. He became a well-to-do writer by this means and through the substantial income he earned from the sale of copyrights, the publication of articles, and the work he did as publisher.

During these years Casgrain published two historical volumes, Histoire de l’Hôtel-Dieu de Québec (Québec, 1878) and Une paroisse canadienne au XVIIe siècle ([Québec], 1880). He also reprinted a number of biographies. In addition he undertook responsibility for publishing Octave Crémazie’s Œuvres complètes (Montréal, 1882), in collaboration with Honoré-Julien-Jean-Baptiste Chouinard. In 1882 as well he became a member of the Royal Society of Canada, and he was to give several lectures before it, mainly on the Acadians.

Casgrain was a great traveller. Between 1858 and 1899 he made 16 trips to Europe and many visits to the United States. He left Canada every winter, because the glare of the sun on the snow hurt his eyes. His travels benefited his health and gave him an opportunity to increase his knowledge and to study the history of Canada in more depth. When he was abroad Casgrain made many contacts, becoming friends with descendants of the great French families and with archivists, librarians, historians, and writers. He used these acquaintanceships to enhance his role as a representative of the French Canadian élite. Besides engaging in these more formal activities, Casgrain spent his time in Europe copying or obtaining copies of documents about Canada and attending lectures, the opera, and the theatre.

Casgrain was also professor of the history of literature in the faculty of arts at the Université Laval from 1887 to 1895, and then professor of history from 1895 to 1904. From 1887 historical writings constituted the major part of his output. In Un pèlerinage au pays d’Évangéline, brought out at Quebec in 1887 and honoured the following year by the Académie Française, he recounted all the misfortunes of the Acadians during their exile. He fostered a better understanding of the history of Canada, not only through his books, but also through the documents he had copied, including the 12-volume collection of the manuscripts of François de Lévis*, published 1889–95, which he edited for the government. His endeavours were to prove immensely valuable to historians of Canada. Casgrain’s Montcalm et Lévis (Québec, 1891) was a major work using contemporary sources to depict the ancien régime. An ardent champion of the Acadian people, he published Une seconde Acadie . . . (Québec, 1894) and Les sulpiciens et les prêtres des Missions-Étrangères en Acadie (1676–1762) (Québec, 1897), books which portrayed the attachment of the Acadians to their religion and the importance of the clergy as leaders.

The year 1898 was marked by a rather deplorable episode in Casgrain’s life: he altered the text of an inscription for the monument at Quebec to Samuel de Champlain*, which Narcisse-Eutrope Dionne* had prepared at the request of a committee. To edit the text without the committee’s consent, take credit for it, and attempt to justify himself in a pamphlet printed in limited numbers shows that he was impressed with his own merit and sought personal honours. He was again seeking his own advantage, as he had done in claiming the author’s copyright to Crémazie’s Œuvres complètes in 1882 and to Aubert de Gaspé’s Les anciens Canadiens in 1883.

Casgrain devoted his last years as an author to his memoirs. His “Souvenances canadiennes,” written between 1899 and 1902, recounts many anecdotes about his life, travels, and acquaintances and relates various episodes illustrating French Canadian customs. In his unfinished work “La vie de famille,” he gives a vivid picture of such typical rural scenes as haying, harvest, flax-crushing, and hunting. After more than 40 years as a writer, he was forced by blindness to end his literary career.

Casgrain’s name is closely connected with the literary history of Canada in the second half of the 19th century. As story-teller, biographer, poet, critic, and historian, he produced some 30 literary and historical works which, despite certain weaknesses, were highly regarded because their romantic style suited the taste of the period. Casgrain believed that a national literature could be created and gave himself wholeheartedly to the cause. By calling for an edifying and patriotic Canadian literature he stimulated writers to produce works that took their inspiration from the Canadian scene. Thus his true ministry in life was to promote wholesome literature, to criticize writers in a kindly manner, and to be their confidant.

As a historian, Casgrain had neither the impartiality nor the exactitude of a Garneau or a Ferland. He was not objective in his interpretation of facts and analysis of documents. Both as critic and as author he looked at history from the viewpoint of a Catholic and a French Canadian, highlighting religious values and extolling the patriotism of French Canadians. Nevertheless, he holds an important place among historians of his time, for he made his narratives lively and presented well-constructed, coherent texts.

Noted as a writer, Casgrain left a body of work in which there is a good deal of local colour. Several of his works portray various aspects of rural life in minute detail. His highly romantic imagination is evident in Légendes canadiennes. However, in addition to pleasant pages with unadorned depictions of French Canadian life, there are negative features, such as his heavy style and, worse still, macabre accounts of the ferocity of the Indians. His biographies of contemporaries were intended as a testimony to those who had helped make Canada better known. Despite frequent digressions, they are based on previously unpublished documents of great interest. Over the years Casgrain acquired a stronger sense of style and produced interesting texts. His memoirs and accounts of his travels were better suited to his manner of writing, since he gave free rein to his pen in setting down not only what he observed and knew, but also what he thought of people and events.

Energetic, vain, and opportunistic, Casgrain led a comfortable life which he enjoyed to the full despite his eye trouble. He was praised by some and criticized by others, but no one who knew him was indifferent to him. Both his activities and his writings make him an important figure in 19th-century Canada. He had an engaging but complex personality, and his occasional acts of pettiness should not be allowed to obscure all that he accomplished in promoting and popularizing Canadian literature, both in Canada and abroad.

The most complete bibliography of Henri-Raymond Casgrain’s writings and of studies about him appears in Jean-Paul Hudon, “L’abbé Henri-Raymond Casgrain, l’homme et l’œuvre” (thèse de phd, univ. d’Ottawa, 1977).

AC, Québec, État civil, Catholiques, Saint-Jean-Baptiste (Québec), 15 févr. 1904. ANQ-BSLGIM, CE4-1, 16 déc. 1832.

Cite This Article

Jean-Paul Hudon, “CASGRAIN, HENRI-RAYMOND,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/casgrain_henri_raymond_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/casgrain_henri_raymond_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jean-Paul Hudon |

| Title of Article: | CASGRAIN, HENRI-RAYMOND |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | December 30, 2025 |