Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

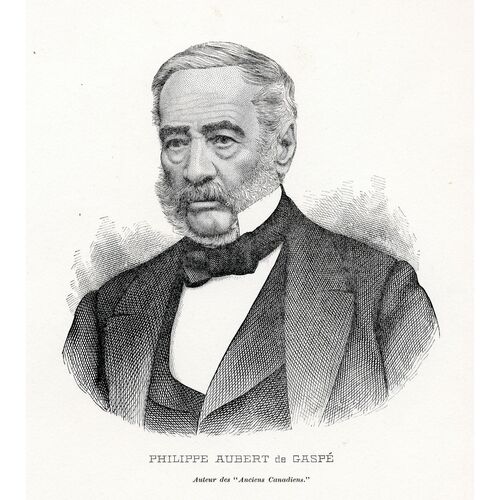

AUBERT DE GASPÉ, PHILIPPE-JOSEPH, lawyer, writer, fifth and last seigneur of Saint-Jean-Port-Joli (L’Islet County); b. 30 Oct. 1786 at Quebec; d. 29 Jan. 1871 at Quebec, and buried in the church of Saint-Jean-Port-Joli.

Philippe-Joseph Aubert de Gaspé was the eldest son of Pierre-Ignace Aubert de Gaspé, a legislative councillor, and Catherine Tarieu de Lanaudière. His father had distinguished himself at the siege of Quebec in 1775, as had his grandfather, Ignace-Philippe*, throughout the Seven Years’ War. The founder of the line, Charles Aubert* de La Chesnaye, an important figure in the fur trade, had arrived in New France in 1655, became subsequently a member of the Conseil souverain, and was ennobled by Louis XIV in 1693. One of his sons, Pierre, was the first to adopt the name Gaspé, in 1709. By his ancestors on both his mother’s and his father’s side, Philippe Aubert de Gaspé belonged to the most illustrious families in Canada bearing names such as Coulon de Villiers, Legardeur de Tilly, Jarret de Verchères, and Le Moyne de Longueuil. He also numbered among his forbears Robert Giffard* de Moncel and Pierre Boucher*.

At an early age Philippe was sent to Quebec; he boarded first with the Misses Cholette (1795–98), then at the seminary of Quebec, where he received his classical education (1798–1806). Louis-Joseph Papineau and the doctors Joseph Painchaud and Pierre-Jean de Sales Laterrière* were his fellow-students. From 1804 to 1806, while taking philosophy at the seminary, he lived at the boarding-school of the Reverend John Jackson, Church of England minister, where he was, he said, the only French Canadian. Afterwards he studied law first under Jonathan Sewell*, the future chief justice, then under Jean-Baptiste-Olivier Perrault*. He was called to the bar on 15 Aug. 1811. On 25 September of the same year, at Quebec, he married Susanne Allison, daughter of Thomas Allison, a captain in the 5th regiment of foot, and Thérèse Baby. Thirteen children were born of their marriage.

The young Gaspé, with a generous and enthusiastic disposition, had every advantage at the beginning of his career: high birth, financial sufficiency, an excellent education, advantageous connections in political, judicial, military, and social circles. He took part in a host of cultural, sporting, and even financial ventures. He was vice-president of the first literary society of Quebec in 1809, and a founding member of the Jockey Club in 1815 and of the Quebec Bank in 1818. In addition, in 1804 he had received a commission as lieutenant in the Quebec and District militia; in 1812 he became a captain in the 1st Battalion of Quebec District, and in the same year was promoted to the general staff of Lower Canada, as deputy judge advocate. He practised law at Quebec and “on the Kamouraska circuit” until 9 May 1816, when he received a commission as sheriff of the district of Quebec. In this capacity it was he who had the responsibility or the honour of proclaiming in the streets of the town, on 24 April 1820, the announcement of the recent accession of George IV to the throne.

Until that time success had thus come readily in everything to this man now in his thirties, who no doubt on that account had lived in the most easy-going contentment. However, by his liberality and want of foresight he had gradually brought himself to the brink of ruin. That ruin was startlingly revealed when “the iron hand of misfortune” descended upon him. In debt to the crown for a large sum of money and unable to reimburse it, he was relieved of his office as sheriff on 14 Nov. 1822. Shortly afterwards, on 13 Feb. 1823, his father died. It was then that he was forced to seek refuge, with his large family, which already numbered seven children, in the manor-house of his mother, the seigneuress of Saint-Jean-Port-Joli.

This forced retirement lasted 14 years, during which he lived in the midst of his family, continually haunted by fear and the threat of creditors who might some day have him imprisoned for debt. And this is what finally happened, on 29 May 1838. To extricate him from this predicament, in a troubled period, required as many negotiations and legal proceedings as had been necessary to get him implicated. They are summarized in a report which a special committee of nine members presented to the Legislative Assembly on 3 Aug. 1841, when commenting on the petition that Gaspé had presented on the previous 18 July. The report shows that he was put in prison in conformity with a judgement delivered against him on 20 June 1834, on behalf of the crown, for the sum of £1,169 14s.; that subsequently, in May 1836, he had attempted to avail himself of the provisions of the law respecting insolvent debtors by transferring all his personal and landed property, an expedient which the Court of King’s Bench had endorsed; but that the Court of Appeal had reversed its decision in November 1836, on the grounds that this statute did not extend to debtors of the crown. The report ended thus: “Considering the long period during which Mr. De Gaspé has been imprisoned, his advanced age [55], and that his health is impaired by his long confinement, and that he has ‘given unto Court, upon Oath, a faithful statement of all the property and estate he possessed in the world,’ with a view to the discharge of his debts, they [the members of the committee] respectfully recommend that an Act be passed for his relief, and accordingly report a Bill for the purpose.”

This bill, ratified by both houses, was passed without amendment on 18 Sept. 1841, and received royal sanction some days later. At the beginning of October Gaspé was therefore enabled to regain his liberty, after a captivity of 3 years, 4 months, and 5 days.

The long period of misfortunes since his dismissal in 1822 does not show items solely on the debit side. True, he was kept apart from public life, where he doubtless might have played an eminent role, but his withdrawal to the country, followed by his seclusion, was a splendid preparation for the literary career that was to add lustre to the last part of his life. First of all, his tribulations made him a wiser man. They led him to look into himself and to reflect deeply upon his past conduct and his family memories. Furthermore, the solitude of the long winters allowed him, while he saw to the education of his numerous children, to complete his own literary education by steady association with authors, both ancient and modern, English and French, through contact with whom his taste was refined. An outcast as it were from urban society, he appreciated all the more the frank, simple companionship of the farmers, the censitaires of the seigneury. He found pleasure in associating with them, and accompanied them on hunting and fishing trips, lending an attentive ear to their talk and their stories, and recording in his prodigious memory the legends, tales, and songs that were to provide material for his books.

More especially, without being clearly aware of it, he acquired his first experience as a novelist through that of his eldest son and namesake. In 1837 the latter published, under his name alone, L’Influence d’un livre. But there is no doubt that the first French Canadian novel bears in more than one place the mark of the father, and not only, according to a tradition that is related by Philéas Gagnon* and Abbé Henri-Raymond Casgrain*, in the legend of Rose Latulipe (chapter five, “L’Étranger”). To support this new interpretation, it is necessary to retrace briefly the career of the son.

Young Philippe-Ignace-François Aubert de Gaspé (1814–41) was tutored by his father before entering the seminary of Nicolet in 1827. Once his studies were completed, or broken off, in 1832, he was for several years a stenographer and journalist with the Quebec Mercury and Le Canadian. Following an altercation with Dr Edmund Bailey O’Callaghan, member of the assembly for Yamaska, who questioned his professional integrity, he was sentenced in November 1835 to a month in prison. In February 1836, to avenge himself, the turbulent protester placed in the hall of the House of Assembly a bottle of asafoetida, which forced the members to evacuate the building. The situation was serious. To escape another warrant for his arrest, he left town and sought refuge in the manor-house at Saint-Jean-Port-Joli, where nobody worried him further. It was there, under his father’s watchful eye, that he composed his novel.

This book recounts the misfortunes of an over-credulous peasant under the spell of Le Petit Albert, a collection of magical recipes by means of which he hopes to acquire wealth. Hence the justification for the title L’Influence d’un livre. The main theme also includes the story of a quack hanged at Quebec for a murder that was actually committed at Saint-Jean-Port-Joli in 1829. The whole is embellished with a little love plot, as well as with legends and folksongs. Absurd though the novel may appear at first sight, and despite many borrowings from books, it is none the less based on the attentive observation of many customs of the time, and on anecdotes some of which the son could have learned only through his father. An example is the hero’s visit to the sorceress Nolet from Beaumont in chapter eight. This is a transposition into the novel of a recollection of 1806 belonging to Gaspé Sr. As the old woman Nolet died in 1819, his son was certainly not able to question her himself. In this way one can establish a series of significant rapprochements between the memories and works of the father and the novel of the son. These cross-checks are in no sense intended to deprive the son of his title of first French Canadian novelist, but rather to emphasize that by 1837 the father had acquired a certain amount of experience in the writer’s trade.

We know that L’Influence d’un livre appeared at a most unfavourable moment, when all people were concerned more with politics and rebellion [see Papineau] than with literature. The author was even the object of sharp criticism. He had stated in his preface: “Public opinion will decide whether I should go no further than this first venture,” and he found he had to defend himself against the attacks of Le Populaire. There was no one to bring him the slightest word of encouragement. On the contrary, a correspondent of La Gazette de Québec concluded, on 10 Feb. 1838, that “great was the disappointment of the subscribers over M. de Gaspé’s historico-poetic mish-mash.” This total lack of comprehension eventually discouraged the young novelist and destroyed his career. Subsequently he went to Halifax to try his luck, and died there suddenly on 7 March 1841, while his father was in prison at Quebec.

It is not impossible that even at this time Gaspé Sr thought of accepting the challenge and taking up the pen that his son had broken. This hypothesis is confirmed to some degree by a contemporary testimony. Aimé-Nicolas, dit Napoléon Aubin* relates in his prison memories (Le Fantasque, 8 May 1839) that “there, buried in his black thoughts, lay Mr Hunter, who, like the old Indian, considered that not enough beavers were being killed in prison.” The allusion to Gaspé is transparent, if we recall that it was precisely around this anecdote that the author of Les Anciens Canadians was to build the speech for his own defence which he attributed to one of his characters.

But before carrying out the plan that was to rehabilitate him in his own eyes and in those of his compatriots, Gaspé had to wait some 20 years for favourable circumstances. In the meantime his existence returned to normal. In October 1841 he was restored to his family, who during his captivity had found shelter at the house of his mother, the seigneuress Aubert de Gaspé, a few steps away from the prison on Rue Sainte-Anne. The seigneuress died shortly afterwards, on 13 April 1842, only a week after her sister, Louise Tarieu de Lanaudière. A double inheritance then brought Philippe Aubert “the usufruct and possession of the fiefs and seigneuries of Port Joly and La Pocatière,” as well as the “other lucrative and honorary rights” that were attached to them. He now went to take up residence on Rue des Ramparts at Quebec, and resumed his summer trips to Saint-Jean.

For several years there is nothing noteworthy in his biography except for the succession of intimate events that are particularly frequent in a large family. His children got married, his daughters making the most advantageous matches available in Lower Canada: Susanne was married to William Power; Adélaïde; to Georges-René Saveuse de Beaujeu; Elmire, to Andrew Stuart*; Zélie, to Louis-Eusèbe Borne; Zoé, to Charles Alleyn*; Atala, to J.-Eusèbe Hudon; and Wilhelmine-Anaïs, to William Fraser. The youngest girl, Philomène, became a nun in France. As for his son Thomas, he became a priest in 1847, the same year that his mother died. Philippe Aubert also discovered and practised early the art of being a grandfather. With his numerous descendants around him, he was able once more to enjoy respect.

Around 1850 and even before, he had begun to frequent Quebec society once more. He was a regular visitor to the Club des Anciens, which met each afternoon during the off season at Charles Hamel’s store on Rue Saint-Jean. There he met the historians and archeologists of the old capital, among others François-Xavier Garneau*, Georges-Barthélemi Faribault*, and the commissary general James Thompson Jr. The conversation of all these veterans usually turned on the antiquities of Quebec. Gaspé more than any others, because of his lengthy absence, was able to gauge the manifold changes that had taken place in the old capital since the beginning of the century. It was before this circle, as well as in family reunions, that he related his memories before writing them down.

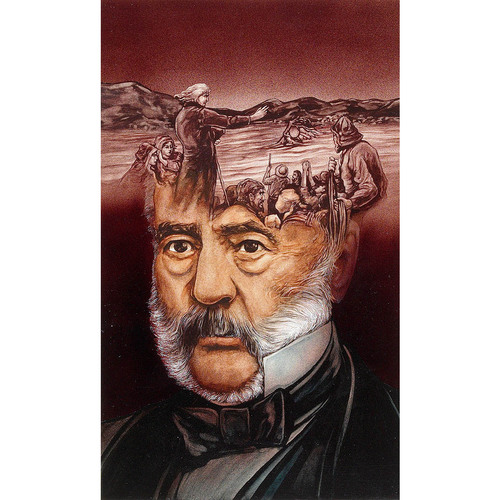

From the first, no doubt thinking of his son, he was minded to give them the form of a novel and to place them at the most crucial moment in the history of New France. A witness of three generations, he had been in his childhood the recipient of the direct memories of the survivors of the old régime. The historical novel, a type of literature conceived after the manner of Walter Scott, one of his favourite authors, offered him the advantage of painting a general picture and at the same time using precise details of seigneurial life as he had lived it at the end of the 18th century or as it had been recounted to him in his family.

Hence the rather simple plot of Les Anciens Canadiens. The spatial setting of the novel is the very places where the author had had his own personal experiences; the main centres of the action are the town of Quebec and the manor-house of Haberville (slight modification for Aubert), to which must be added the picturesque trip along the south shore, with the old servant José Dubé as a mentor. The first part, which covers a good half of the novel (11 chapters), describes at some length seigneurial customs in 1757, at the end of the French régime. Traditional elements are deliberately given first place: the legends of the sorcerers of the Île d’Orléans and the appearance of “la Corriveau” [Marie-Josephte Corriveau*], the spring break-up, the popular feasts of the first of May (the planting of the fir-tree) and Saint-Jean, elaborate meals served as occasion requires, the paying of the seigneurial rents, etc. The protagonists are two young men who on leaving college propose to follow a military career: Jules d’Haberville, the seigneur’s son, in the French army, and Archibald Cameron of Locheil, a Scottish orphan brought from France to New France by the Jesuits after the disaster at Culloden in 1746, in the English army. They are given a warm welcome at the Haberville manor-house before they leave for Europe.

The action of the second part (three chapters only) takes place during the war of 1759. It is the climax of the collective and individual drama. The workings of destiny have brought the two young officers back to New France, but in opposite camps. Archy receives from the invader a ruthless order to burn the dwellings on the south shore, including the manor-house of his former protectors. The dictates of military discipline and honour prevail over his reluctance to carry out this sinister plan. But, taken prisoner by the Indians, the young officer escapes torture and death only because of the gratitude of Dumais, a Canadien whom he had formerly rescued from certain drowning. A little later, on the Plains of Abraham, at the time of the battle of Sainte-Foy, Archy comes face to face with his former comrade and friend. He magnanimously spares Jules d’Haberville’s life, when he has him at his mercy.

The third part, also short (four chapters), tells the story of slow reconciliation after terrible years of anguish. In it Gaspé makes a critical assessment, as it were, of the misfortunes that befell New France after the shipwreck of the Auguste; then he shows the changes that occurred around 1767 in the environment in which his characters move. As wounds are not entirely healed, Blanche d’Haberville refuses the hand of her suitor Archy, but Jules marries an English girl. And the final episode of the novel portrays a typical scene of the times, with songs, dances, and mirth bringing back gaiety to the Haberville manor-house.

This not improbable plot was only a pretext for Gaspé, whose ambition was above all to “set down some episodes of the good old days.” He received, he said, the encouragement of “some of our best writers, who begged me to omit nothing concerning the customs of the Canadians of old”; he was referring to such men as Faribault, his lifetime friend, Octave Crémazie, who wrote a prefatory poem on Quebec specially for Gaspé’s book, and Joseph-Charles Taché*, whom he entrusted with his first chapters for publication in Les Soirées canadiennes. But he was none the less fearful of unkindly criticism. Consequently he informed purists that he was more aware than anybody of the weaknesses of his book. Let them, he exclaimed, “call it a novel, memoirs, a chronicle, a mish-mash, a hotch-potch: I care little!” The last two expressions, which do not strictly speaking represent literary categories, were without a doubt recalled to his mind by the unfavourable reception given earlier to L’Influence d’un livre.

But his fears were exaggerated. On 3 Jan. 1863 he read the manuscript to Abbé Casgrain; he had already published two chapters in January and February 1862. Casgrain immediately took it to Georges-Pascal Desbarats*, the publisher of Le Foyer canadien, where it appeared at the beginning of April. It was an immediate success. In 1864 there was a second edition “revised and corrected by the author,” as well as an English translation, The Canadians of old. In 1865 the novel was adapted for the stage. One can say after more than a century that the popularity of this work has never declined. To the present time there has been a total of some 20 editions, including three English translations and one Spanish. The work’s popularity is due not so much to the Corneille-like dilemma that faces the principal characters as to the personal recollections of the author, which abound on each page and even overflow into notes and explanations every bit as worthy of attention as the plot itself. This is because the writer of memoirs is everywhere present behind the novelist. The characters themselves are all identifiable prototypes in the family circle or among the former relations of the Gaspé family. For example, José is an old servant the author actually knew in his youth. Archy was suggested to him by an episode in the life of Lieutenant-Colonel Malcolm Fraser*. Moreover, he depicted himself at two periods of his life, first through the impulsive, spirited nature of young Jules d’Haberville, then in the person of Monsieur d’Egmont, an old man grown wise through trials similar in every respect to those Gaspé had experienced himself during his years of tribulation.

The Mémoires published by Gaspé in 1866 are the natural sequel to the notes and explanations in Les Anciens Canadiens. Once freed from the limitation of the novel form, the old author – he was then 80 – allowed his pen to run on at the command of his memory, which he himself called outstanding. He also had a high opinion of his propensity for always telling the truth. “I was born naturally truthful,” he stated. Indeed, these are two qualities in which he is rarely found wanting. But there is another of which he does not boast, although he finds a way to praise it in others. That is the kindness, accompanied by a touch of humour, with which he surrounds the persons of whom he speaks. As their number exceeds a thousand, the effect is the more remarkable.

It is not easy to summarize the Mémoires, which do not unfold in a strictly chronological order. Roughly speaking, the author lingers more over the years previous to 1822, except in so far as his friends, the habitants of Saint-Jean-Port-Joli, are concerned. If he makes only brief mention of his helpmeet, “beautiful among the beautiful,” and speaks only a little of his children, it is because he is writing for them. On the other hand, he never ceases to talk about the early generations of his ancestors, the families friendly with his own, and in general the society he frequented: students of the seminary of Quebec, lawyers, judges, doctors, military men, ecclesiastics, and politicians.

About each of the names he mentions he recalls anecdotes, a little at random, as he must have done during casual conversation. In short, his art is that of a brilliant conversationalist, and therefore of a story-teller. The anecdotes contained in the Mémoires, taken as a whole, constitute one of the best pictures we possess of Canadien society, both urban and rural, at the beginning of the 19th century. Above all Gaspé, although an aristocrat, was the first to make heard through a written work the pleasing voices of the habitants of the country. For his period, his work provides an unrivalled description of popular traditions of all kinds.

In a word, on many events and on a vast number of people, Gaspé sheds a light resulting from a balanced judgement, which makes the Mémoires, as also the posthumous fragments collected under the title of Divers (1893), a human testimony of major importance for Canadian history and literature. By his irreplaceable work the author of Les Anciens Canadiens and Mémoires thoroughly redeemed the errors of his youth. He became the most illustrious of his line to bear the name of Gaspé. Like Alfred de Vigny he might have said, paradoxically, had it not been for his modesty: “My ancestors will spring from me.”

AQ, Autographes, ff.68–73. Archives de l’université de Montréal, Collection Baby, Correspondance générale, dix lettres de Philippe Aubert de Gaspé. Archives du collège Bourget (Rigaud, Qué.), Philippe Aubert de Gaspé, Les Anciens Canadiens. Archives judiciaires de Montmagny (Qué.), Greffe Simon Fraser, 17 juin 1841. ASQ, Cartons, S, 110; Cartons, T, 128, 130; Fonds Casgrain, I, 115, 118–19; Fonds Casgrain, II, 17, 20.

Philippe-Joseph Aubert de Gaspé, Les Anciens Canadiens (1re éd., Québec, 1863; 2e éd., revue et corrigée par l’auteur, 1864; 16e éd., 1970); The Canadians of old, trans. G. M. Pennée (1st ed., Quebec, 1864), trans. C. G. D. Roberts (3rd ed., New York, 1898); Divers (1re éd., Montréal, 1893); Mémoires (Ottawa, 1866). Philippe Aubert de Gaspé (fils), L’Influence d’un livre; roman historique (1re éd., Québec, 1837).

D. M. Hayne et Marcel Tirol, Bibliographie critique du roman canadien français, 1837–1900 (Toronto and Quebec, 1968), 42–59. H. R. Casgrain, Philippe Aubert de Gaspé (Québec, 1871). V. I. Curran, “Philippe Aubert de Gaspé; his life and his works,” unpublished phd thesis, University of Toronto, 1957. [François Daniel], Histoire des grandes familles françaises du Canada . . . (Montréal, 1867), 347–70. P.-G. Roy, A travers les « Anciens Canadiens » de Philippe Aubert de Gaspé (Montréal, 1943); A travers les « Mémoires » de Philippe Aubert de Gaspé (Montréal, 1943); La famille Aubert de Gaspé (Lévis, Qué., 1907). André Bellessort, “Les souvenirs d’un seigneur canadien,” Reflets de la vieille Amérique (Paris, 1923), 216–58. Narcisse Degagné, “Philippe Aubert de Gaspé, étude littéraire,” Revue canadienne (Montréal), 2e sér. XXI (1895), 456–78, 524–51. Charles ab der Halden, “Philippe Aubert de Gaspé,” Études de littérature canadienne française (Paris, 1904), 43–52. Luc Lacourcière, “L’enjeu des Anciens Canadiens,” Cahiers des Dix, XXXII (1967), 223–54; “Philippe Aubert de Gaspé (fils),” Livres et auteurs canadiens, 1964; panorama de la production littéraire de l’année (Montréal, [1965]), 150–57. Camille Roy, “Les Anciens Canadiens,” Nouveaux essais sur la littérature canadienne (Québec, 1914), 1–63.

Cite This Article

Luc Lacourcière, “AUBERT DE GASPÉ, PHILIPPE-JOSEPH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 21, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/aubert_de_gaspe_philippe_joseph_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/aubert_de_gaspe_philippe_joseph_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | Luc Lacourcière |

| Title of Article: | AUBERT DE GASPÉ, PHILIPPE-JOSEPH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1972 |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | December 21, 2024 |