As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

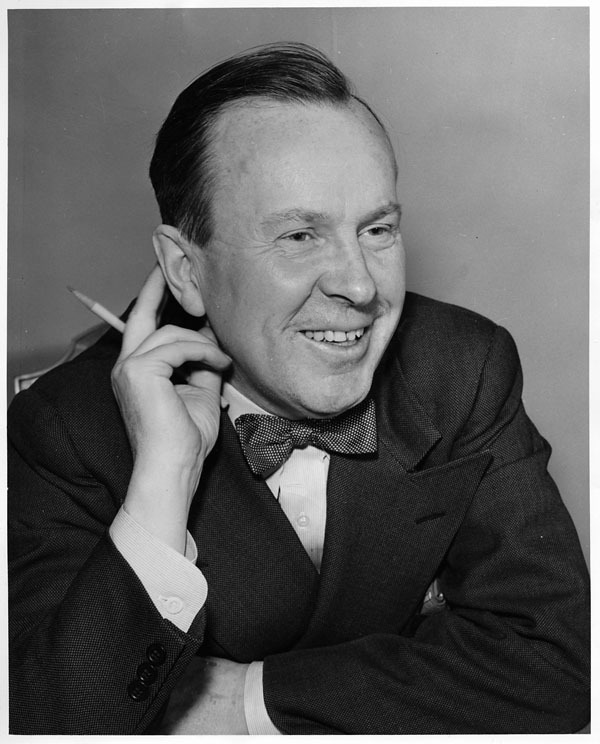

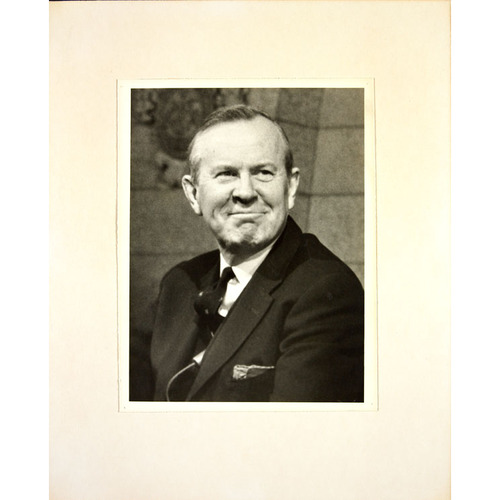

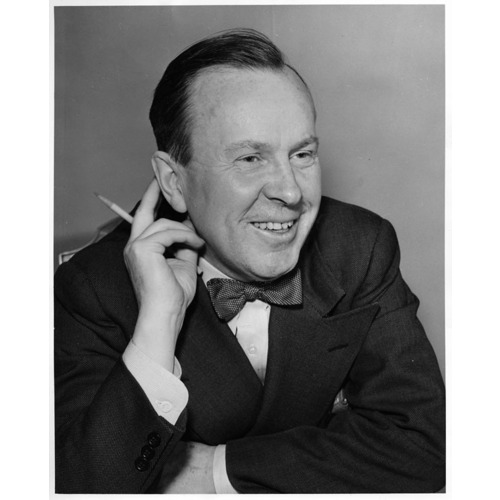

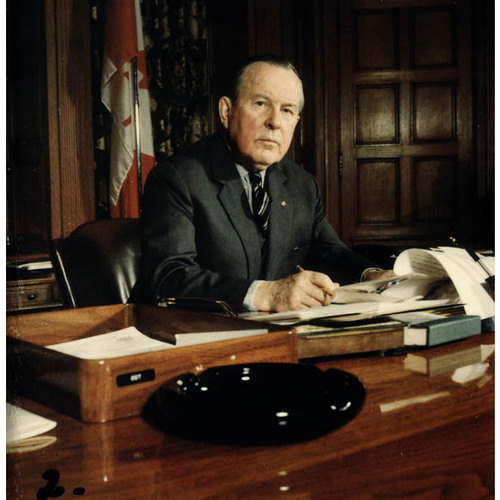

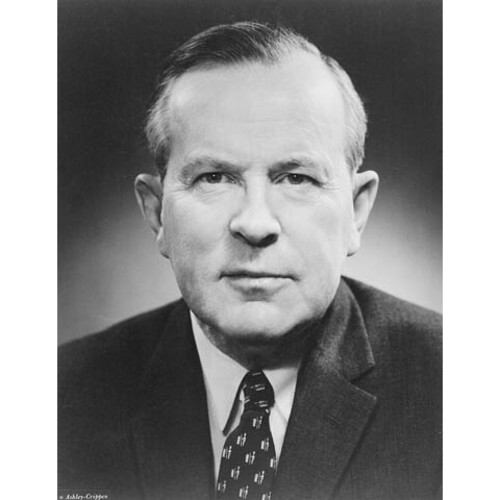

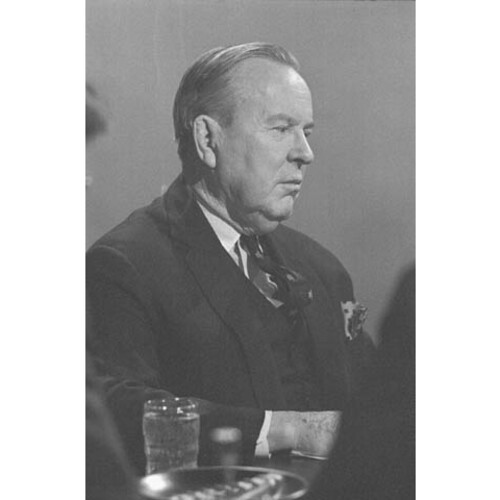

PEARSON, LESTER BOWLES, professor, office holder, diplomat, and politician; b. 23 April 1897 in Newton Brook (Toronto), second of the three sons of Edwin Arthur Pearson, a Methodist minister, and Annie Sarah Bowles; m. 22 Aug. 1925 Maryon Elspeth Moody in Winnipeg, and they had a son and a daughter; d. 27 Dec. 1972 in Ottawa.

Born on St George’s Day in the year of Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee, Lester Pearson would be brought up in a home that reflected fully the ambitions and character of Canadian Methodism in the last decade of the 19th century. Although neither the Bowleses nor the Pearsons were notably religious in Ireland before they emigrated, they became enthusiastic and prominent Methodists after their arrival in Canada, in the 1820s and 1840s respectively. Pearson’s paternal grandfather, Marmaduke Louis, was a well-known Methodist minister; his mother’s cousin the Reverend Richard Pinch Bowles, later the chancellor of Victoria University, Toronto, had officiated at the marriage of Annie and Edwin. Edwin Pearson stepped aside from the heated debates about the Social Gospel that marked early-20th-century Methodism. Athletic and easygoing, he was a popular pastor who moved often because he received calls from other churches.

The family’s frequent changes of residence meant that Lester did not have a home town, but the values of the various places in southern Ontario where he lived were strongly defined. Alcohol was loathed, education celebrated, and the sabbath holy. Edwin was a strong imperialist whose scrapbook is filled with clippings about the royal family; his three boys shared his enthusiasm for sports and the empire. An excellent student in high school, Lester is revealed in the diary of his second year at Victoria University as a polite young man whose enthusiasm for sports exceeded his interest in his courses. He referred to his parents fondly and respectfully. His brother Marmaduke (Duke) had left university as soon as he turned 18 to fight in Europe during World War I. As the war intensified, Lester became ever more eager to volunteer. On 23 April 1915 he enlisted in the University of Toronto hospital unit and became a private in the Canadian Army Medical Corps. His younger brother, Vaughan, would soon be overseas as well.

Although Pearson would later claim in his memoirs that the war was a decisive event in his development, his presentation of its impact is not supported by contemporary evidence. Like many others, he was to argue that his experience of the war disillusioned him. However, his letters home, his comments in a diary reconstructed from wartime scribblings, and his writings during the early 1920s indicate that he remained conventional in his attitudes. In common with most English Canadians, he had strongly supported conscription in 1917, continued to look to Great Britain for leadership, and honoured the fallen as heroes.

Pearson’s own war service reveals an unachieved desire for heroism. After very basic training, he had arrived at the quiet front in Salonica (Thessaloníki, Greece) on 12 Nov. 1915. Greece was neutral, but the British and French stationed troops in the region of Macedonia to minimize contact between the Bulgarians and their Austro-Hungarian allies. Almost immediately, Pearson sought transfer to the Western Front. Thanks to the intervention of the Canadian minister of militia and defence, Sir Samuel Hughes*, a fellow Methodist, a transfer to Britain finally came. After arriving in England in late March 1917, Pearson went for training to Wadham College, Oxford, where his platoon commander was the famous war poet Robert von Ranke Graves. When he finished training, he and his brother Duke decided in late summer to become aviators instead of infantry officers.

In the most glamorous and dangerous of combat roles in World War I, the aviator had a life expectancy of months. Pearson joined the Royal Flying Corps in October and began his aerial training at Hendon (London). Two months later his career ended, as he later said, “ingloriously,” when a bus struck him during a London blackout. His medical and other records indicate that the accident did not disable him, but that he broke down emotionally in the hospital and during recuperation in early 1918. He was sent home to Canada on 6 April, after a medical board declared him “unfit” for flying or observer duties because of “neurasthenia.” The war changed Pearson as it did his nation. His resentment of persons in authority, especially British officers, strengthened his democratic and nationalistic instincts. His emotional breakdown probably contributed to his tendency to keep his feelings private and to deplore irrationalism in public and personal life. The war also gave him the enduring nickname of Mike.

Pearson tried to return to the war, but the medical board denied him his wish. He had constant headaches, trembled, and could not sleep. He joined the staff of No.4 School of Aeronautics at the University of Toronto and lived at Victoria once again. After the war, he enrolled at Victoria and became a star on the playing field and in the arena. Sports played a major role in his recuperation and would remain a central part of his life until his final years. He received credit for war service and graduated ba with a specialization in modern history in June 1919. He then began articling with the Toronto law firm of McLaughlin, Johnston, Moorhead, and Macaulay, but left quickly to play semi-professional baseball in Guelph, where his father was a pastor. Like many other young Canadians of the day, he found better prospects in the United States. He and Duke joined Armour and Company, an important meat company in Chicago of which their uncle was president. After a brief apprenticeship stuffing sausages in a Canadian subsidiary, Pearson went to Chicago in February 1920.

There he began work as a clerk in the fertilizer division of the Armour empire. The anti-British tone of Chicago politics, where the Irish and the Germans held sway, offended the young imperialist and business did not attract him. He told his uncle and his parents that he wanted to go to Oxford. With the help of a fellowship from the Massey Foundation, he left for St John’s College in the fall of 1921. At Oxford, he achieved a solid second, but once again impressed his tutors and fellow students more with his sporting skills and his wit. He took a two-year ma degree and returned to Toronto as a lecturer in the university’s department of history in 1923. In that small unit he made lasting friends, such as the future diplomat Humphrey Hume Wrong*; he also met his wife.

The daughter of a Winnipeg doctor and nurse, Maryon Moody enrolled in Pearson’s history tutorial for the fall term of 1923 in her final year at university. The attraction was immediate and within a few weeks the professor had persuaded his pretty female student to attend a party with him. On 13 March, five weeks later, Maryon wrote to a close friend, “Don’t tell a soul because we aren’t telling the public till after term. I am engaged.” She admitted that she had “known him really at all well [for] a little over a month” but they “loved each other more than anything else in the world.” They were married in Broadway United Church, Winnipeg. Their son, Geoffrey Arthur Holland, who would become a diplomat, was born in December 1927 and daughter Patricia Lillian arrived in March 1929.

Maryon is one of the most interesting of the Canadian prime ministerial wives. Deeply religious as an undergraduate, she became a sceptic and, privately, a non-believer. Excited about the possibility of a life as a writer, she would never work in a paying job after her marriage. Against Pearson’s enemies, she was a ferocious defender of her husband. After his death, she would be bereft and resentful of her widowhood. Yet when they were together, she was known for her barbed comments directed towards her spouse, as when she famously said, “Behind every successful man there is a surprised woman.” They fought often and both had close relationships, perhaps affairs, with others. She despised politics but would take a close interest and would influence critical decisions, especially the selection of Pearson’s cabinet. Her sharp and sardonic wit wounded some, but enlivened many dinner parties. She and her husband moved together along the modernist paths of the 20th century in their choices in literature, their attitudes towards religion, and even in their methods of child rearing, but they remained grounded in the traditions of Anglo-Canadian Methodism. In a later time, they might have divorced, but they would remain a couple, forming a partnership that deeply influenced their times and their country.

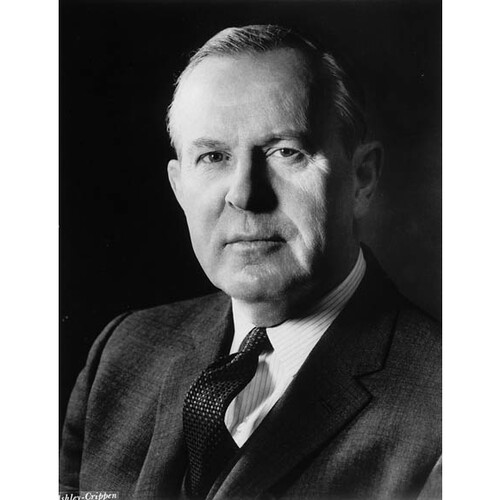

After their marriage the Pearsons lived close to the university and entertained young faculty in their home. Reports vary on Pearson’s success as a lecturer, but all agree that he was a major figure in the athletic activities of the university and a minor contributor to the professionalization of the field of Canadian history in the 1920s. He proposed to write a book on the loyalists and spent the summer of 1926 at the Public Archives of Canada in Ottawa. At the university, he faced a choice between accepting promotion through which he would become a major figure in the athletic department or demonstrating stronger devotion to scholarship and the classroom. Both options lacked the appeal of the Department of External Affairs in Ottawa which, under Oscar Douglas Skelton*, the under-secretary of state, was hiring bright young Canadians with advanced degrees. Wrong, Pearson’s closest friend in the history department, went to Washington as a junior diplomat in the spring of 1927 and Skelton expressed interest in Pearson, whom he had met in the summer of 1926. Pearson took the foreign service examination and stood first among a distinguished group of applicants. He had, at last, a métier.

Hugh Llewellyn Keenleyside*, another academic who became a foreign service officer in the late 1920s, shared an office with Pearson in Ottawa after Pearson’s arrival in August 1928. Pearson, he would later write, was in “good physical shape, vigorous and alert.” He was “cheerful, amusing, keenly interested in his work, ambitious for the service and for himself.” He remained so throughout his career in the department. There would be frustrations, especially with Skelton’s lack of organizational skills and the idiosyncrasies of prime ministers Richard Bedford Bennett* and William Lyon Mackenzie King*. Nevertheless, Pearson’s intelligence, artfully concealed ambition, good looks and health, and exceptional personal charm were qualities that identified him as an extraordinarily effective public servant and diplomat.

The times were bad in the early 1930s, but the opportunities for Pearson were many. In a small department attached to the office of the prime minister, he found himself with different tasks. He attended the London Naval Conference in 1930, meetings of the League of Nations, and the first World Conference on Disarmament in Geneva in 1932, but in Ottawa his major work was in the field of domestic politics. He served as secretary to the royal commission to inquire into trading in grain futures in 1931 and the royal commission on price spreads in 1934-35. His skills impressed Bennett, who recommended him for an obe in 1935, the same year he posted him to London in the prestigious position of first secretary. As would occur often in his life, Pearson found himself at the centre of an international whirlwind and managed to keep his balance in turbulent times.

Pearson began his European experience badly when he advised the Canadian representative to the League of Nations, Walter Alexander Riddell*, to put forward a proposal to impose sanctions on Italy after it invaded Abyssinia (Ethiopia) in October 1935. King, who became prime minister later that month, angrily repudiated the Riddell initiative in December, but Pearson escaped blame. King and Skelton had both lost faith in the League of Nations and fretted about British policy towards European border tension and the Spanish Civil War that they feared would lead to confrontations, not only with Italy but, more dangerously, with Adolf Hitler’s Germany. Pearson shared some of these concerns in 1936 and 1937, but his views differed from those of his political superiors as Hitler’s ambitions grew. When King “rejoiced” at the Munich agreement of 1938 between Hitler and British prime minister Arthur Neville Chamberlain, Pearson dissented in a letter to Skelton. Munich was not a peace with honour, he wrote. “If I am tempted to become cynical and isolationist, I think of Hitler screeching into the microphone, Jewish women and children in ditches on the Polish border, [Hermann] G[ö]ring, the genial ape-man and [Paul Joseph] Goebbels, the evil imp, and then, whatever the British side may represent, the other does indeed stand for savagery and barbarism.” It was fine to be on the side of the “angels,” but Pearson knew that “in Germany the opposite spirits are hard at work. And I have a feeling they’re going to do a lot of mischief before they are exorcised.”

These comments reveal much about Pearson and his success as a diplomat and international security analyst. He was pragmatic but deeply principled and his principles were based upon a liberal conviction that brutal dictatorships not only repress many of their own citizens but also threaten the security of democratic nations. Moreover, he had sufficient confidence in his perceptions and his accomplishments to disagree with his superiors, a risky course for any public servant. Finally, he had become, by the late 1930s, a superb analyst of international politics and personalities. The British often turned to him for advice and he began to gather a group of international supporters who would assist his career. When the war began in September 1939, he was well placed to influence Canadian policy, particularly since he had told his doubting superiors that war would come and that Canada must fight.

The children, and then Maryon, returned to Ottawa, but Pearson stayed in England and worked ceaselessly to strengthen British-Canadian ties. Those times remained a cherished memory for him and their spirit is preserved in the diary of his colleague Charles Stewart Almon Ritchie* and the novel, The heat of the day (London, 1949), written by Ritchie’s lover, Elizabeth Dorothea Cole Bowen. The death of Skelton, however, forced Pearson’s return to Ottawa in the spring of 1941 and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, in December took him to Washington as minister-counsellor in June 1942. He arrived just as the centre of wartime decision-making was shifting to Washington from London and there was no doubt that the United States would dominate in reconstructing the international system after the war. The Canadian minister to Washington, Leighton Goldie McCarthy, was weak and Pearson quickly took on the major role in representing Canada, not only to the American government but also in the numerous committees that were the birthplace of post-war international institutions. Unlike many Canadians and most Britons, he had realized as early as 1940 that power had shifted from London to Washington and that the British Commonwealth of Nations would be a secondary actor on the international stage. For Canada, the political and economic implications of these changes were enormous.

Pearson quickly captured attention, especially from the American news media. He became a minor celebrity on a radio quiz program and, significantly, a close friend of several major American journalists. His diplomatic colleagues noted his skill in presiding over committees and in July 1943 he became the chair of the United Nations Interim Commission on Food and Agriculture. The committee was to become the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN in October 1945. Pearson would decline the chance to head the new institution. From 1943 to 1946 he also chaired the important committee on supplies of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. On 1 Jan. 1945 he became Canada’s second ambassador to the United States (earlier representatives had been ministers). He had become one of the foremost diplomats of the time and, in Canada, a public figure.

Pearson knew the United States well and admired its energy and creativity. Unlike his brother Duke, now a businessman and a Republican, he was an enthusiastic supporter of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the New Deal. He enjoyed American popular culture, especially its cinema, Broadway musicals, and, above all, baseball. Nevertheless, he thought American democracy too encumbered by major financial interests, its public life too vulgar, and its self-confidence sometimes abrasive. As Canada moved from its British past to its North American future, he anticipated many problems. Some in his department had written very negative comments on American policy, but he was always a pragmatist. In 1944 he had written: “When we are dealing with such a powerful neighbour, we have to avoid the twin dangers of subservience and truculent touchiness. We succumb to the former when we take everything lying down, and to the latter when we rush to the State Department with a note everytime some Congressman makes a stupid statement about Canada, or some documentary movie about the war forgets to mention Canada.” This advice to a junior colleague neatly defined his central approach to Canadian-American relations throughout his diplomatic and political career.

Although unhappy about the shape of the UN and, especially, the dominance of the Security Council by the great powers, Pearson did not protest as strongly as the Australians did at the San Francisco Conference, where delegates met to draw up the charter in 1945. When the new organization took form, many favoured him for the post of secretary general. He was, however, too closely identified with American interests to satisfy the Soviets. He also knew that political changes were occurring quickly in Ottawa and he did not encourage friends who wanted to promote his candidacy. King was leaving and he had already spoken with Pearson about “entering Canadian public life,” and the diplomat had the idea “very much in mind.” To assure Pearson’s presence in Ottawa as King slowly took his retirement, the prime minister appointed him under-secretary of state for external affairs. Pearson returned to Ottawa in September 1946. He served under the new secretary of state for external affairs, St-Laurent. The two quickly acquired confidence in each other and shared their doubts about the weary prime minister. As a minister from the traditionally isolationist Quebec and as King’s favoured successor, St-Laurent gave Pearson valuable cabinet and political support for an innovative and energetic foreign policy. He needed such backing because King was wary of Pearson’s enthusiasms and his tendency to commit Canada to international agreements and institutions.

The Cold War between the Soviet Union and the west was young but fierce during Pearson’s tenure as under-secretary. The Soviet use of the veto handcuffed the UN’s Security Council and Soviet influence in eastern Europe became control as coalition governments in nations such as Czechoslovakia and Poland fell to Communism. Although the war’s end did not bring depression as it had in 1919, the economic future was uncertain, since Canada’s traditional European markets were either destroyed or, in the case of Britain, essentially bankrupt. Pearson took three major policy initiatives between 1946 and 1948. First, he continued to hope that the UN would gain strength and, much to King’s despair, he backed UN involvement in the settlement of conflict in Korea and in other troubled areas such as Palestine. Secondly, he recognized the economic and political predominance of the United States. The shortage of American dollars in Canada was solved initially by a special arrangement and Pearson was willing to work out a free trade agreement with the Americans. King stopped the free trade negotiations, fearful of their political impact. Finally, Pearson tried to balance American influence by the creation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and he argued strongly for a socio-economic component to the pact. He played a major role in the discussions and persistently urged Canada’s chief negotiator, Hume Wrong, to take a broad approach to the treaty. By the time the pact was finally signed in Washington in the spring of 1949, his numerous accomplishments had gained him further recognition. With the strong encouragement of King and St-Laurent, he entered politics and was appointed secretary of state for external affairs in the St-Laurent government on 10 Sept. 1948. He ran successfully for a seat in the House of Commons in a by-election in Algoma East on 25 October and retained the seat in the general election of 1949, in which St-Laurent’s government won a resounding victory. He would represent the riding throughout his political career.

Pearson would remain Canada’s minister of external affairs until the defeat of the Liberals in 1957. Historians have called his times the “golden years” of Canadian diplomacy. Although there are justifiable doubts about the glitter of the period, Pearson’s own reputation retains its lustre. He had unusual freedom because of the consensus within the Liberal Party and the commons on the nature of the Soviet threat. His department was talented, strong, and well funded. The times were especially kind to him. He was a unilingual anglophone who had little experience outside London, Ottawa, New York, and Washington, but for a Canadian minister of external affairs in the 1950s little else mattered. He recognized that the rebirth of the European economies would make Canada a relatively less significant actor within the western alliance. He also acknowledged that Canada’s relationship with the United States had become the principal concern of a Canadian foreign minister. He nonetheless retained his pre-war unease that the United States was sometimes an “intoxicated” nation and, in that state, “middle courses” were difficult to follow. Yet there was no doubt that the Canadian course in the Cold War years must follow closely behind the American juggernaut. Occasionally, a clever Canadian initiative could alter the course slightly, but Canada and the United States were on the same journey.

In the late 1940s Pearson worried that the United States would revert to pre-war isolationist tendencies and his rhetoric and policies reflected this concern. Beginning in the 1960s, critics such as Robert Dennis Cuff and Jack Lawrence Granatstein would point to Pearson’s strong and, in their view, strident anti-Communist speeches and his sternly anti-Communist policies in the first years of the Cold War, a position later adopted by historian Denis Smith, political scientist Reginald Whitaker, and journalist Gary Marcuse. These revisionists would suggest that Pearson overestimated the dangers of Soviet Communism. Pearson equated Communism with Nazism. He warned, for example, that “we did not take very seriously the preposterous statements of the slightly ridiculous author of Mein Kampf. We preferred the friendly remarks of ‘jolly old Goering’ at his hunting lodge.” Mein Kampf had been the true agenda; similarly, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin showed a gentle side to the American vice-president, Henry Agard Wallace, in 1944, but Pearson warned that the west should look at Stalin’s harsh statements, “which form the basic dogma on which the policy of the USSR [Union of Soviet Socialist Republics] is inflexibly based.”

This debate about the Cold War and the threat of Communism, the so-called revisionist debate, has changed since the Cold War’s end in the late 1980s. On the one hand, the opening of Soviet archives has revealed that Stalin was extraordinarily dangerous and cruel and that Soviet espionage had infiltrated Western security and foreign policy establishments more fully than revisionist historians had suggested. Pearson’s evaluation of the menace was probably more accurate than his critics had thought. On the other hand, the opening of Canadian security files and greater attention to individual rights in Canadian society has drawn attention to discrimination against, and sometimes persecution of, not only political dissidents but also homosexuals in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The argument that Pearson’s strident anti-Communism had contributed to the climate of fear that stifled dissent has some merit. Pearson had little patience with those who made revisionist arguments and the second volume of his memoirs is a reply to the revisionist historians of the late 1960s and early 1970s. On the question of treatment of dissidents, he would have had some sympathy because his support of Egerton Herbert Norman*, a Canadian diplomat accused by an American congressional committee of being a Communist agent, had made him very much a target of American extreme anti-Communists.

Although Pearson did not speak out publicly against the activities of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in harassing dissidents, he did annoy the Federal Bureau of Investigation and some Republican politicians, including Senator Joseph McCarthy. He refused to allow Soviet defector Igor Sergeievich Gouzenko to testify in the United States before the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee and denied that Canadian information confirmed that Harry Dexter White was guilty of espionage. (White was a senior American public servant who is now known to have been an agent of influence for the Soviets.) His refusal to dismiss Norman made John Edgar Hoover of the FBI suspicious of him. The Chicago Tribune, owned by Hoover’s friend Colonel Robert Rutherford McCormick, called Pearson “the most dangerous man in the Western World” in 1953. These attacks and incidents deeply annoyed him, but they did not significantly affect his ability to work with the American administration under President Harry S. Truman and, after his taking office in 1953, under Republican president Dwight David Eisenhower.

The confidence in Pearson among senior Department of State and other American officials had come from his role in promoting the creation of the North Atlantic alliance, his support for American policy in the creation of Israel, and his encouragement of much higher Canadian defence spending after 1949. When the Korean War broke out in 1950, Canadian public opinion was not strongly in favour of Canadian participation. On 25 June, Pearson told journalists privately that he did not believe UN or American intervention would occur. Three days later, after learning that Truman had decided to intervene, he praised the United States for recognizing “a special responsibility which it discharged with admirable dispatch and decisiveness.” He, like Truman, believed that such an intervention under the leadership of the United States and the auspices of the UN - which was possible because the Soviets were boycotting the Security Council - would call the Communists’ bluff and strengthen the UN, whose first years had been very disappointing. At his urging, the Canadians raised their commitment from a token naval presence to a significant involvement in the brutal ground war.

Because of the war in Korea and the perceived threat of a Communist attack on western Europe, Pearson had unusual freedom from normal political restraints. He chaired the NATO council in 1951-52 and in 1952 became the president of the UN’s General Assembly. As president, he had difficulties with the Americans, for he had become a critic of their policies in Asia. Canada had followed the United States in refusing to recognize Communist China, but he had been deeply concerned about the possibility that the war in Korea would become a broad conflagration after the Chinese entered it in November 1950. When American general Douglas MacArthur, the commander of the UN forces in Korea, spoke openly about extending the war, Pearson decided that he must protest. In a famous speech to the Canadian and Empire clubs in Toronto on 10 April 1951, he said that the UN must not be the “instrument of any one country” and that others had the right to criticize American policy. He expressed his belief that “the days of relatively easy and automatic political relations with our neighbour are, I think, over.” And they were, even though Truman fired MacArthur later the same day.

While sharing the American conviction that the expansion of Communism must be halted and contained, Pearson deplored talk of “rolling back” Communism and worried about American excesses. The attack of Senator McCarthy and his allies on the Department of State was, in his view, dangerous and thoroughly irresponsible. The American policy on China especially bothered him. He told his son, soon to become a foreign service officer, that he had attempted and failed to moderate American attitudes toward China. In the winter of 1951 it seemed to him that “emotionalism has become the basis of [United States] policy.” Canada would still “follow” the Americans, but only to the extent of their strict obligations under the UN charter. The Korean War finally came to an end after Eisenhower became president. Pearson had irritated American secretary of state Dean Gooderham Acheson because of his insistence on advancing peace negotiations. Acheson’s Republican successor, John Foster Dulles, was even more difficult and ideological in his approach and Pearson became more determined to find ways to end the Cold War chill, especially after the death of Stalin in 1953.

Despite Pearson’s disagreements with the Americans, they recognized his skill and usefulness. When, in 1952, his name had come forward for the positions of NATO’s secretary-general and the UN’s secretary-general, the United States had supported his candidacy. He had resisted the NATO post and the Russians, as before, had rejected him for the UN appointment. He established strong personal ties with the Scandinavian countries and in the British Commonwealth he and Canada became an influential force. The Colombo Plan, which had been drawn up in January 1950, was Canada’s first major commitment to assistance for developing countries and Pearson had been one of its architects. Although he thought Jawaharlal Nehru puzzling, he fostered the notion of a special relationship between Canada and India. Canada participated in the Geneva Conference of 1954 that sought, unsuccessfully, to bring peace to French Indochina. Canada became the Western voice on the International Control Commission that, again unsuccessfully, attempted to supervise and develop a peace settlement in the region. In October 1955 he was the first Western foreign minister to visit the Soviet Union after the death of Stalin. The trip, which featured a wild night of drinking and debate with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev in the Crimea, did not persuade Pearson that the post-Stalin Soviet Union was a more benign state.

Pearson’s focus remained firmly on the Soviet threat and he believed the United States was weakening itself and its response to that menace by excessive attention to Communist China. He considered recognition of Communist China, but American warnings of retaliation quickly dissuaded him. He was furious, as were the Americans, when the British, the French, and the Israelis, angry about the Egyptian takeover of the Suez Canal, secretly planned and carried out an attack in Egypt on 29 Oct. 1956. The Soviets began to talk of sending volunteers to aid the Egyptians; the Americans, who had not been informed of the plans, moved to condemn their traditional allies in the UN. The Australians backed the British; Canada, for the first time in its history, opposed a British war. Working closely with the Americans, Pearson tried to craft a solution that would end the divisions among Western allies and would reduce the tensions of a broader war. Early on Sunday morning, 4 November, the UN supported a Canadian resolution that called for the creation of a peace force. The British and French backed down. On 14 Oct. 1957 Pearson would receive the Nobel Peace Prize.

Although Pearson gained international laurels, the Canadian position on the Suez crisis met with strong criticism in English Canada. Reluctant to abandon the British ties that had been the foundation of their identity for almost two centuries, many English Canadians linked the Liberal government and Pearson with the increasing Americanization of Canada. They complained that the Liberals had favoured the Americans and had “knifed” Britain in the crisis. The irascible Conservative Charlotte Elizabeth Hazeltyne Whitton, mayor of Ottawa, quipped: “It’s too bad [Gamal Abdel] Nasser couldn’t help Mike Pearson to cross Elliot Lake [in his constituency] when Mr. Pearson did so much to help him along the Suez Canal.”

The Liberals, with St-Laurent as leader, Pearson as his likely successor, and a Gallup poll forecasting another solid majority, called an election for 10 June 1957. The polls were wrong; Progressive Conservative leader John George Diefenbaker’s appeal to Anglo-Canadian nationalism was effective in western Canada, the Maritimes, and British Ontario. His eloquent denunciation of the Liberal minister of trade and commerce, Clarence Decatur Howe*, and the pipeline fiasco had also persuaded electors to vote Conservative. The American-born Howe had used closure to force a bill through the commons to create an American-financed pipeline which would bring western natural gas to Ontario. The Conservatives had opposed it bitterly because of American involvement and had sung “God save the queen” to emphasize their traditional British-Canadian nationalism. The Conservatives won 112 seats with over 38 per cent of the vote and the Liberals 105 seats with over 40 per cent of the vote. After some indecision, St-Laurent resigned as prime minister and as Liberal leader. Pearson was the strong favourite in the Liberal leadership race, especially after he was awarded the Nobel Prize. He became head of the party on 16 Jan. 1958.

Pearson’s victory left him foolishly confident and his first efforts in the commons were feeble. When he called upon the new government to resign, Diefenbaker, with his brilliant sense of parliamentary timing, ridiculed the motion and on 1 February asked for a general election, to be held on 31 March. The Liberals were in disarray and the campaign soon revealed how effective Diefenbaker could be on the hustings and how unprepared Pearson was. Although Pearson and Diefenbaker were of similar background and age, Diefenbaker was the more energetic and convincing campaigner. The Conservatives won the most decisive victory recorded in Canadian federal politics, 208 seats compared to only 49 for the Liberals and 8 for the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation. With characteristic black humour, Maryon Pearson remarked, “We’ve lost everything. We even won our own seat.”

Pearson briefly considered resignation; Maryon encouraged it. He was over 60, a Nobel Prize winner, and aware that his speaking style did not suit an age when television dominated politics. He considered other offers, but his friends, notably Toronto businessman Walter Lockhart Gordon*, encouraged him to stay. Diefenbaker was a better campaigner than prime minister and the economy was faltering after the long post-war boom. Pearson decided to stay on.

The election of Jean Lesage’s Liberal Party in Quebec in June 1960 presented new challenges for the Conservatives, who had won in 1958 because of strong support from the Union Nationale under Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis*. Pearson began to develop new policies that would reflect the liberalism of Lesage and, to some extent, of John Fitzgerald Kennedy, who was to become president of the United States in January 1961. In September 1960, just after the Liberals moved ahead of the Conservatives in a Gallup poll, the party held a study conference in Kingston. Pearson drew upon his network of friends in journalism, the universities, business, and politics to create a debate about the future of Canadian Liberalism and to draft a platform for the next Liberal government.

Prior to the conference, two of those friends, Gordon and journalist Thomas Worrall Kent, had been wary of each other. At the conference, they worked together to draft a progressive platform, one that reflected Kennedy’s New Frontier policy and the ambitious programs of the Quebec government. Pearson became increasingly concerned about Quebec and he insisted that greater recognition of the French language and of the rights of French Canadians be part of the new Liberal platform. When Diefenbaker called a general election for 18 June 1962, many expected him to lose. The Liberal members had been extremely effective in the commons and Diefenbaker’s ministers had fumbled badly. Nevertheless, the final results were 116 Conservatives, 100 Liberals, 30 Social Crediters/Créditistes, and 19 New Democrats. Despite the loss, it was a triumph for Pearson. Diefenbaker’s government began to crumble. When he hesitated to support the Americans in the Cuban missile crisis of October 1962, not only the Kennedy administration but also many traditional Conservatives turned against him. The confusion surrounding the acceptance of nuclear weapons caused turmoil within the Conservative Party; the minister of national defence, Douglas Scott Harkness*, was a strong proponent of acceptance and the minister of external affairs, Howard Charles Green*, a strong opponent.

Pearson had opposed nuclear weapons for Canada, but on 12 Jan. 1963 he declared that the country must accept them because it had made a commitment to its allies in 1958 to arm the Bomarc anti-aircraft missiles located in northern Ontario and Quebec with nuclear warheads. Complaints came quickly from Quebec intellectual Pierre Elliott Trudeau* and, privately, from Walter Gordon and the young Liberal Norman Lloyd Axworthy. Pearson’s announcement split the Conservatives and some ministers tried to secure Diefenbaker’s resignation. They failed, but on 5 Feb. 1963 the government fell. Most expected Pearson to win the election, called for 8 April.

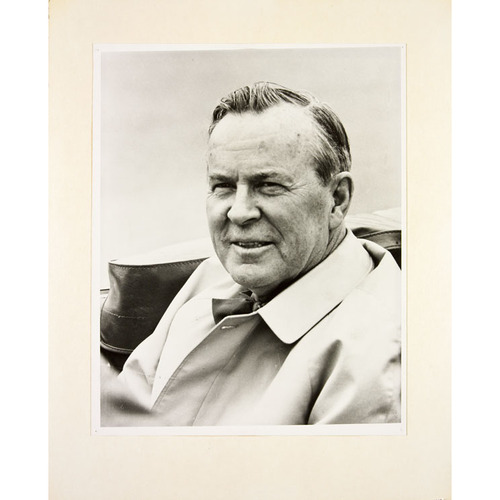

Pearson became prime minister on 22 April, but the majority government that public opinion polls had predicted and that he had craved eluded him. The Liberals had obtained 129 seats and the Conservatives 95, while the Social Crediters/Créditistes and New Democrats held the balance with 24 and 17 respectively. The following day he turned 66, an age when many Canadians had retired. His cabinet impressed Canadian journalists with its regional balance and broad experience. Paul Joseph James Martin* had served in parliament for 28 years. Newfoundland’s John Whitney Pickersgill* was Diefenbaker’s equal in the house. Gordon, Mitchell William Sharp*, and Charles Mills Drury* brought business experience. Guy Favreau*, the major Quebec minister, and Maurice Lamontagne* were respected in Quebec and Ottawa. The poor results in western Canada, however, meant weak representation from that region.

During the election campaign Pearson had promised “sixty days of decision,” but the first two months went badly. Gordon had supported Pearson financially since he had entered politics, had organized his leadership campaign, and had brought influential and capable friends into the Liberal Party. He expected to be minister of finance, but Pearson knew that many in the business community did not have confidence in Gordon’s nationalistic views. Nevertheless, over his wife’s objections, he made the appointment. Gordon turned to outside advisers to prepare the budget because he thought the Department of Finance would be unwilling to accept his nationalist policies. He presented his budget, with a withholding tax on dividends paid to non-residents and a “takeover tax” on foreign acquisitions of Canadian businesses, on 13 June 1963. Bureaucrats complained about his use of outside advisers and many in the business community expressed hostility toward his nationalism. The lack of western Canadian voices in the Liberal caucus meant that their traditional suspicion of Ontario-based nationalism was not often expressed in party debate. The president of the Montreal Stock Exchange, Eric William Kierans*, who would later become a nationalist ally of Gordon’s, attacked the budget, claiming that “our friends in the western world” would realize that “we don’t want them or their money and that Canadians who deal with them in even modest amounts will suffer a thirty percent expropriation of the assets involved.” The attack was unfair, but it and other criticisms led Gordon to withdraw the tax on foreign acquisitions on 19 June. The response was a call for Gordon’s resignation by many major newspapers.

Gordon offered his resignation the next day; Pearson refused. Nevertheless, the distrust between the two friends grew. Pearson himself paid little heed to the details of the budget, but the appearance of a separatist movement in Quebec had captured his full attention. On 21 April 1963 a bomb placed by Quebec separatists had killed a janitor working in a Canadian army recruiting office. On 17 May dynamite had exploded in mail boxes in Montreal. Quebec journalist André Laurendeau* had recommended, in January 1962, a royal commission to investigate bilingualism and Pearson had promised to act. On 19 July 1963 he appointed Laurendeau and Arnold Davidson Dunton* co-chairs of the royal commission on bilingualism and biculturalism, and the so-called Quebec issue became the major domestic concern of Pearson’s years in office. The royal commission was immediately controversial, although few suggested that the question of Quebec’s role in Canadian confederation could be ignored. Critics, especially in the west questioned the focus on the duality of Canada and, though the commission’s terms of reference provided that other ethnic groups should be studied, argued for a broader approach that reflected the diverse origins of the country’s population. The seeds of multiculturalism were born.

The Pearson government stumbled regularly between 1963 and 1965. Gordon never recovered from the budget debacle and Pearson proved no match for Diefenbaker in the cut and thrust of parliamentary debate. The most serious problem was Quebec representation in the cabinet. Pearson’s support for the acceptance of nuclear weapons had weakened his position in Quebec. The nationalist Le Devoir (Montréal) attacked his stand and urged consideration of the New Democrats’ stance opposing nuclear weapons; prominent francophones such as Trudeau and labour leader Jean Marchand* retreated from flirtation with the Liberals. The result was weak Quebec representation in Ottawa. The veteran Lionel Chevrier was the major Quebec minister even though he was, by origin, a Franco-Ontarian. Justice minister Favreau was able, but he was a political novice. Lamontagne, an excellent academic economist, was an uncertain politician. When, therefore, the increasingly nationalistic government of Jean Lesage in Quebec countered the federal government in domestic jurisdiction and, more troublingly, in international relations, the government response lacked force. Pearson’s Quebec ministers seemed ineffectual and unable to face the challenge of a strong provincial government. The impact was immediate in the area of social policy, where the Liberal agenda was ambitious. The Quebec government anticipated a federal contributory pension scheme by presenting its own plan. It argued, with the support of other provinces concerned about federal intrusion into provincial domains, that it was within its rights. Despite strong opposition in the Liberal caucus and cabinet, Pearson agreed that the Quebec plan should be the starting point for a national program. Quebec could “opt out” of the national plan with compensation and could have its own scheme, aligned with the national one. He cleverly guided the agreement through the cabinet and the Canada and Quebec Pension plans would become a reality in 1966.

Despite its clumsy start and its minority status, the Pearson government implemented some social legislation over its two mandates, including the Canada Assistance Plan, which funded provincial welfare programs (1966), and the Guaranteed Income Supplement (1967). In addition, there was much more funding for university research and university capital expenditures. The government had created the Canada Student Loans Plan in 1964. Combined with provincial support for post-secondary education, these policies transformed the Canadian university system. Pearson was fortunate in that the Canadian economy was strong during his tenure as prime minister. Starting in 1965 and culminating with the creation of an apolitical Immigration Board in 1967, important changes were made to Canada’s immigration policy. Under the leadership of the powerful Quebec minister Jean Marchand, who had been persuaded to join the Liberal Party and enter the cabinet, it was closely linked to the government’s labour policy.

Although health is an area of provincial responsibility, the Liberals had promised a health care program in their platform of 1919, had dangled it before the electorate in 1945, and had made it part of the platform in 1963. The successful but very difficult creation of such a program in Saskatchewan by its socialist government in 1961 had set a standard that Pearson knew the Liberals must match, especially since the Saskatchewan premier, Thomas Clement Douglas*, had become leader of the federal New Democratic Party that year. Pearson did little to shape the Canadian Medicare program, but he did challenge the reluctant provinces, notably Ontario, to accept that Canadians must have equal access to state-provided medical services. Parliament passed the Medical Care Act in 1966 but financial exigencies postponed its operation for a year. The effect of this social legislation was to make Canada more European and less American in its approach to social welfare. There had been no counterpart to Roosevelt’s New Deal, but Canada caught up quickly in the 1960s and moved well beyond the American standard.

If Canada became less American in its approach to social welfare, it became less European in its symbols. The country had no national flag and Liberals had occasionally proposed one. Despite such musings, King and St-Laurent had wisely avoided the controversial issue. Pearson, however, was determined and in 1964, against the advice of many, he insisted on pushing forward. Diefenbaker rallied British Canadians in defence of the Union Jack and the Red Ensign; Liberals told Pearson that he was creating political difficulties over a purely symbolic issue. Nevertheless, he persisted and in the commons on 15 December, with the help of the New Democrats, he managed to secure approval of a design. Liberal mp John Ross Matheson, a war veteran who championed the new flag, would later write that “the fight for a flag became a crusade for national unity, for justice to all Canadians, for Canada’s dignity.” Not all Canadians agreed; many Conservative members wept and the province of British Columbia would not raise the new flag in daylight on its inaugural day. As for the French Canadians, who one might expect to have welcomed the new flag, Trudeau claimed that they did not give “a tinker’s damn” about it.

This flood of legislation was broken up by a general election. The weakness of the Pearson government in the matter of Quebec representation had been made worse by scandals that left even fewer French Canadians in the cabinet. These scandals were the face of national politics that Canadians viewed in 1964 and 1965 and they did not like what they saw. There was, as journalist Peter Charles Newman would later write, a “distemper” in Canada during Pearson’s time in office. Writing in 1990 about his 1968 book on the Pearson years, Newman would recall that “most of the people” he had talked with in airports, at dinner parties, and around hamburger stands were “voicing a dismay at our politics that was hardening into cynicism or despair.” The scandals were the manifestation of profound changes in the Canadian political system that occurred during the 1960s. In the case of the Mafia-linked drug dealer Lucien Rivard, ministerial assistants and even Pearson’s parliamentary secretary had supported Rivard’s attempt to obtain release on bail. More seriously, a ministerial assistant had tried to bribe the lawyer acting on the American request for Rivard’s extradition. Justice minister Favreau was drawn into the fray when he decided not to prosecute the assistant. He told Pearson about the developing scandal in September 1964 but Pearson left the impression that he had not learned about it until November. Finally, Pearson corrected the impression in a letter to the special public inquiry, headed by justice Frédéric Dorion, which he had created to investigate the scandal. Favreau’s reputation was shattered; Pearson’s was damaged. Lamontagne and immigration minister René Tremblay saw their careers destroyed over their failure to pay for furniture from a bankrupt Montreal dealer. Yvon Dupuis, another Quebec minister, although later acquitted, was fired from cabinet because he faced criminal charges involving the acceptance of a bribe to accelerate the granting of a racetrack licence. In the commons, Diefenbaker’s courtroom skills cut through the weak answers of the Liberal ministers and his list of French names linked with the scandals, pronounced in halting French, infuriated francophones.

Drug deals, bribes, and sleazy furniture sales were not as titillating as Canada’s major political sex scandal, the so-called Munsinger affair. Gerda Munsinger had been involved with the Soviets in Germany. While living in Montreal she had had an affair with a Russian lover and, simultaneously, from 1958 to 1960 with Pierre Sévigny*, Diefenbaker’s associate minister of national defence from 1959 to 1963. The relationship attracted the interest of the RCMP and wiretaps. In the heat of debate in the commons on 4 March 1966, Liberal justice minister Lucien Cardin taunted Diefenbaker about the “Monseignor case.” Rumours billowed about the involvement of a Tory minister with an apparently dead but once very sexy spy. Yet another inquiry engaged Canadians’ curiosity and exposed Sévigny. Diefenbaker and Pearson had both behaved badly, the prime minister in calling for the RCMP file on Munsinger and, in Diefenbaker’s view, threatening him with revelations unless the Conservative leader relented in the commons. For his part, Diefenbaker had dragged up old charges that Pearson had passed information to Communists when he was in Washington.

The scandals, the bad mood in the house, and the growing divisions in the Conservative Party persuaded Liberal organizers to call an election. The economy was strong and Oliver Quayle, the American pollster hired by Gordon, reported a Liberal upsurge in the spring of 1965. Although Quayle admitted that Pearson’s image was not strongly positive and that most Canadians thought he was doing only a “fair job,” 46 per cent believed that he would be a better prime minister than Diefenbaker, favoured by 23 per cent of Canadians. Faint praise indeed and enough to cause hesitations. Pearson finally called an election for 8 November after Gordon assured him that he would win a majority and that he would resign if the Liberals failed to obtain one.

Diefenbaker once again proved to be an excellent campaigner, overcoming a large Liberal lead in the initial polls. The Liberals pointed to a remarkable list of achievements: the Canada-United States Automotive Products Agreement (Autopact), the pension legislation, student loans, a revision of the tax system, greatly expanded support for post-secondary and technical education, bilingualism and biculturalism, and a more liberal immigration policy that appealed to new Canadians. Diefenbaker shifted debate away from these issues towards Lucien Rivard’s “escape” from prison, the free furniture for cabinet ministers, and Pearson’s lacklustre leadership. Pearson’s campaign was marred by protesters and, at the final giant rally in Toronto, the failure of the sound system. In Quebec, he had recruited three candidates to rebuild the shattered Quebec front bench: journalist and social activist Gérard Pelletier*, Marchand, and, controversially because of his criticism of the Liberals’ nuclear policy, Trudeau. When the campaign ended, the Liberals had won less of the popular vote than in 1963 and, with 131 of 265 seats, were denied a majority. The Conservatives had obtained 97 seats and the NDP 21, with Créditistes, Social Crediters, and independent candidates making up the balance.

Pearson offered his resignation to cabinet; it was refused. Gordon submitted his resignation to Pearson; to his disappointment, it was accepted. The Gordon team, which included Keith Davey, Richard O’Hagan, James Allan Coutts, and Kent left with him. In a study of the Liberal Party, Joseph Wearing correctly suggests that the Gordon approach concentrated on urban Canada and especially Toronto, Gordon’s home. It was the achievement of the group that so-called Tory Toronto would be no more; however, the aftermath of 1965 was the shift of attention and power to Montreal and Quebec.

Quebec increasingly preoccupied the government after the election of 1965. Pelletier, Marchand, and Trudeau had entered federal politics because they feared that Quebec would drift towards separation as Lesage’s Liberals became increasingly nationalist. The surprising defeat of the Liberals by the Union Nationale in 1966 created a sense of crisis. The new premier, Daniel Johnson*, spoke of “equality or independence” and the defeated Liberals, especially the highly popular René Lévesque*, began to muse about an independence platform for their party. Simultaneously, the French government under Charles de Gaulle lavished attention on visiting Quebec politicians while regularly snubbing Canadian representatives. As a diplomat who had seen how the ties of the British empire came undone so quickly, Pearson believed that the French behaviour was profoundly dangerous and that Quebec’s demands for its own foreign policy bore the seeds of the disintegration of Canada. Despite these doubts, which were not fully shared by his minister of external affairs, Paul Martin, Pearson accepted the demands of de Gaulle that he begin his visit during Canada’s centennial year in Quebec City and that he arrive on a French warship, the Colbert.

De Gaulle toured Quebec City on 23 July 1967 and, after some controversial statements, travelled to Montreal the following day. There, on the balcony of the Hôtel de Ville, he made his famous declaration, “Vive le Québec libre!” A furious Pearson declared the remarks “unacceptable” and de Gaulle returned to France without visiting Ottawa. Although the event did not break the buoyant spirit of centennial year, it did underline the divisions within Canada. French newspapers tended to believe that Pearson overreacted while English newspapers expressed outrage. Within the government, Trudeau and several officials (notably Allan Ezra Gotlieb, Peter Michael Pitfield, Marc Lalonde, and Marcel Cadieux) met regularly to counter what they considered the drift in the federal government’s policies in the face of Quebec’s initiatives. They began to formulate a strong response to French support for separatism and to the constitutional demands of Quebec. With Trudeau as justice minister, the agenda shifted to, on the one hand, a more coherent constitutional program and, on the other, a more liberal social agenda that responded to the spirit of the times. Trudeau’s famous statement that the government had no place in the bedrooms of the nation signalled a revolution in its attitude toward private behaviour, one that was far from the ethos of the manse where Pearson had been born or, for that matter, the Catholic home and schools of Trudeau’s early years.

Because of Pearson’s own distinguished background in external affairs, he had retained responsibility for a few issues in this department, delegating responsibility for the remainder to his minister, Paul Martin, and government officials. The Commonwealth was a prime ministerial gathering and there Pearson demonstrated his extraordinary diplomatic skills in dealing with Britain and others on the difficult Rhodesian and South African issues. There was one notable exception to his diplomacy: his decision in April 1965 to speak out against American bombing of North Vietnam. Pearson had had earlier meetings with President Lyndon Baines Johnson and had become concerned about Johnson’s style and determination to achieve victory in Vietnam. Like other Canadians, he gave Johnson much latitude because of the difficult circumstances of his accession to power after Kennedy’s assassination and because of the apparent extremist character of Barry Morris Goldwater, who had been the Republican presidential candidate in 1964. Nevertheless, the build-up of American forces in Vietnam troubled him greatly. He feared that the United States would be drawn into a long war and that the North Atlantic alliance would be fundamentally weakened. After conversations with American friends, he decided to call for a halt to the bombing. Martin and the Department of External Affairs opposed the idea, but Pearson used the occasion of an award he was to receive from Temple University in Philadelphia on 2 April 1965 to call for “a suspension of air strikes against North Vietnam at the right time” in order to provide “Hanoi authorities with an opportunity, if they wish to take it, to inject some flexibility into their policy without appearing to do so as the direct result of military pressure.” These careful words brought an invitation to meet Johnson later that day at his Camp David retreat in Maryland. There Johnson berated and swore at Pearson and made his displeasure clear to the press. Their relationship never recovered, although later, in 1966, Pearson agreed to the use of a Canadian diplomat, Chester Alvin Ronning, as a messenger to the North Vietnamese. Canada, ironically, had benefited from the increased defence purchases that came with the Vietnam War and many Americans of draft age had migrated to Canada and contributed much to Canadian life, especially in the universities. Vietnam, the race riots in Detroit and other American cities, and the assassination of President Kennedy were causes of the surge of Canadian nationalism that occurred in English Canada during the centennial year of 1967.

Pearson called a press conference for 14 Dec. 1967 and announced he would resign in the new year. The Conservatives had a new leader, Robert Lorne Stanfield*, and were ahead in the public opinion polls. Pearson’s caucus and cabinet were restless as they prepared to face an election and a possible loss. More troubling to Pearson was the issue of Canadian national unity and he began to work quietly to assure that his successor came from Quebec. His first choice was Marchand, but Marchand recommended Trudeau, whose intellect had impressed Pearson, but whose political skills had not. Pearson did not designate Trudeau his successor, as King had done with St-Laurent, but he told his closest friends that Trudeau was his choice. It was, he believed, the only bet worth taking, given the challenges from Quebec. It was a bet he won. Despite his recent re-conversion to Liberalism, Trudeau won the convention and had parliament dissolved before Pearson’s colleagues and foes could pay tribute to him. The journalist and former mp Douglas Mason Fisher later recalled that in April 1968, when Pearson left office, there was an atmosphere of “indifference” and “a notable keenness by his successor to separate his government distinctly from the bad Pearson years - scandals, leaks, messy, staggering parliaments and disorganized ventures.”

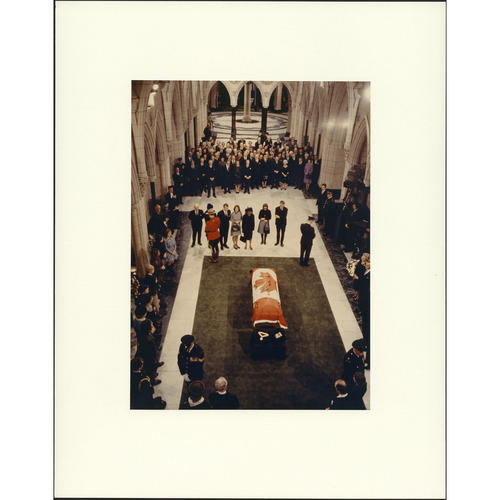

In 1968 Pearson became chancellor of Carleton University in Ottawa and he lectured there in history and political science until the fall of 1972. He chaired a historic commission on international development. Its report, Partners in development: report of the Commission on International Development (New York, 1969), called for a systematic transfer of resources and attention from the rich west and north to the poor south. The so-called “Pearson Report” was the first sustained evaluation of international development assistance. It deeply influenced future debate and policy. Pearson had seldom seen Trudeau after 1968 and the new government’s foreign policy review, with its criticism of post-war strategies, deeply wounded him. Still, he publicly and privately supported Trudeau in the general election of 1972. By that time he knew that he would not vote again. He told his old friend Senator Keith Davey that he would not be able to share his dismay if his beloved Toronto Maple Leafs did not make the playoffs in the spring. He had known since 1970 that cancer would soon cause his death. Despite Maryon’s hopes, he would not retire. On learning of his cancer diagnosis, he rushed his memoirs to publication. The first of his three volumes appeared in 1972 and was an immediate best-seller. His elegant prose and self-deprecating wit made it the finest prime ministerial memoir. It contributed to what Fisher called the rapid “hallowing” of Pearson after his death on 28 Dec. 1972.

The hallowing persisted as Canadians faced continuing challenges to national unity and political independence. When, in 2003, the journal Policy Options (Montreal) asked 30 Canadian academics and public figures to rate Canadian prime ministers since King, Pearson took the majority of first-place votes; Diefenbaker, his great antagonist, won none and finished sixth. One suspects Pearson would have smiled wryly and not taken the results very seriously. Neither should the historian.

One of the most severe critics of Pearson was his former colleague at the University of Toronto, historian Donald Grant Creighton, whose biography of Sir John A. Macdonald* Pearson had generously praised in a personal letter to Creighton. Creighton, like Pearson, was the son of a Methodist parson, a graduate of Toronto and Oxford, and a historian by training, but in the 1950s their agreement about the character of Canadian history and nationality had dissolved. For Creighton, the loss of British identity and the post-war political and economic integration with the United States were giant steps on a path leading towards Canada’s disintegration. The events of the 1960s - the rise of Quebec separatism and secular nationalism, the promotion of biculturalism and bilingualism, and the deluge of American popular media - made Canada’s first century a study in decline and disappointment.

For Pearson, the British empire, whose traditions he had cherished as a youth and a young man, had become a hollow shell by the 1940s. Somewhat regretfully, he acknowledged its decline and recognized its flawed North American successor. Despite his doubts about American policy and about some elements of its society and culture, he linked Canada more closely with the United States in the 1940s and 1950s, mainly because he believed that the greatest threat facing Canada and the world was the Soviet Union and that the United States must give leadership in confronting that challenge. He also accepted that Canadians individually could benefit economically from integration with the strongest economy in the world. A politician had to deliver the goods and, in those days, the Americans had the most and the best.

It was Pearson’s experience as a politician and as a diplomat that persuaded him in the 1960s that French Canada must become more integrally part of the Canadian political and economic system or it would go its separate way. Although he knew little about French Canada or about Quebec, he made Quebec’s place in Canada the focus of his government, thus slowing the momentum for separation. The bitterness of Canadian politics during the mid 1960s derived in part from the sea change that came with the integration of French Canadian politics into the policy centres of the Canadian government. Never again would a Canadian cabinet have a few francophone ministers who could not speak their own language in cabinet and whose deputies dealt with them in English. After Pearson, no Canadian prime minister was unilingual. Ottawa became a different city, Canada a different country.

If he had not become Canada’s prime minister, Pearson would still be a significant figure in Canadian history as the country’s only Nobel Peace laureate and the most eminent Canadian diplomat. Some may cavil, as Creighton did, about Pearson’s work as a diplomat, but few deny his skill and influence. His prime ministerial tenure, however, remains controversial. During his turbulent and fairly brief years in office, his governments transformed Canada. Although Canadians did not want a more open immigration policy, his governments introduced it, transforming the face of urban Canada. Although bilingualism was controversial, the Pearson governments adopted it and set the framework for an official policy that made the federal public service so different from what it had been. Although social welfare was, constitutionally, a provincial responsibility, the Pearson governments legislated boldly in the field and made Canada a country unlike its American neighbour, which had previously been the more generous North American nation in its social policies. Later in the 20th century, social disturbances in Canadian cities, separatism in the province of Quebec, and neo-conservative philosophies made some question the achievement of the Pearson years. Yet foes and friends already recognize that Pearson was a remarkable Canadian whose life and work profoundly changed the country he served.

The major primary source for this biography is the Lester B. Pearson fonds at Library and Arch. Canada (Ottawa) (MG 26, N). It contains an abundance of public papers, Pearson’s correspondence with his colleagues, and a diary that he occasionally maintained. The collection is particularly good for the period between 1935 and 1948, when his career as a foreign service officer advanced quickly.

Material there and elsewhere on his early years is sparse. Some letters to his parents exist, but exchanges with his brothers and friends before 1928, when he entered public service, are missing. Even afterwards, there is little family correspondence. Because of their frequent long separations, correspondence between Maryon Elspeth Pearson and her husband would probably have been abundant, but she apparently destroyed nearly all of it. This biography did benefit from letters between Pearson and his children held by Geoffrey Arthur Holland Pearson of Ottawa and Patricia Lillian Pearson (Hannah) of Toronto. The correspondence between Geoffrey, a foreign service officer, and his father is especially valuable since his father often expressed sharp views on the personalities and events of the time. After he became minister of external affairs, however, Pearson rarely commented frankly or extensively on individuals.

Many other manuscript collections at Library and Arch. Canada offer extensive information on Pearson. The William Lyon Mackenzie King papers (MG 26, J) have much that is relevant to any study of Pearson and there are many comments on him and his ambitions in King’s diary. The Louis St-Laurent papers (MG 26, L) are less useful, but Pearson’s activities in the late 1940s and early 1950s are described well in the records of the Department of External Affairs (RG 25) and in its Documents on Canadian external relations, ed. R. A. Mackay et al. (24v. to date, Ottawa, 1967-?). Because Pearson was one of the most eminent diplomats of the time, the records of the British Foreign Office and its successor, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, held by the National Arch. (London, Eng.) and the records of the American Department of State (RG 59) at the National Arch. and Records Administration (Washington) offer many comments on him and his activities. On the whole, the British documents are a richer source.

The papers of John George Diefenbaker at the Right Honourable John G. Diefenbaker Centre for the Study of Canada, Univ. of Saskatchewan (Saskatoon), provide a sustained criticism of Pearson’s political career. Before he became a minister in the Pearson government in 1967, Pierre Elliott Trudeau had also been a frequent critic of Pearson and his remarks are found in his papers at Library and Arch. Canada (MG 26, O). Other collections with Pearson material include the Arnold Danford Patrick Heeney fonds (MG 30, E144) and especially the Walter Lockhart Gordon papers (MG 32, B44), both at Library and Arch. Canada, the Tom Kent fonds at Queen’s Univ. Arch. (Kingston, Ont.), and the Bruce Hutchison fonds (MsC 22) at the Univ. of Calgary Library, Special Coll.

Pearson wrote the best prime ministerial memoirs: Mike: the memoirs of the Right Honourable Lester B. Pearson, pc, cc, om, obe, ma, lld (3v., Toronto, 1972-75). The first volume, 1897-1948, is superb, although guarded in discussing personal affairs. The second, 1948-1957, edited by J. A. Munro and A. I. Inglis, is a solid academic account of Pearson’s career as minister of external affairs. The last volume, 1957-1968, also edited by Munro and Inglis, regrettably was completed after his death and does not possess the voice and accuracy of the first two. As a public figure, Pearson also published numerous books of speeches and reflections. The best is Words and occasions: an anthology of speeches and articles selected from his papers (Toronto, 1970), which brings together some of his early essays and speeches. Others include: Democracy in world politics (Toronto, 1955), Diplomacy in the nuclear age (Toronto, 1959), Peace in the family of man: the Reith Lectures, 1968 (Toronto and New York, 1969), and The Commonwealth, 1970 (Cambridge, Eng., 1971).

There are several biographies of Pearson. The longest is John English, The life of Lester Pearson (2v., New York and Toronto, 1989-92), divided into two periods, Shadow of heaven, 1897-1948 and The worldly years, 1949-1972. Earlier biographies include Robert Bothwell’s perceptive Pearson: his life and world, gen. ed., W. K. Lamb (Toronto, 1978), the popular J. R. Beal, The Pearson phenomenon (Toronto, 1964), W. B. Ayre, Mr. Pearson and Canada’s revolution by diplomacy ([Montreal, 1966]), and Bruce Thordarson, Lester Pearson, diplomat and politician (Toronto, 1974). Another work that has Pearson as a principal player is the academic study by Joseph Levitt, Pearson and Canada’s role in nuclear disarmament and arms control negotiations, 1945-1957 (Montreal, 1993), which should be read with G. A. H. Pearson’s Seize the day: Lester B. Pearson and crisis diplomacy (Ottawa, 1993).

There are several contemporary works that deal with Pearson’s controversial tenure as prime minister. P. C. Newman’s two books Renegade in power: the Diefenbaker years (Toronto, [1963]) and The distemper of our times: Canadian politics in transition, 1963-1968 (Toronto, [1968]; repr. with new intro., 1990) are important in the history of Canadian journalism and are deeply informed, though highly critical. Similarly, some of Pearson’s colleagues have been critical of his leadership, notably Julia Verlyn (Judy) LaMarsh in Memoirs of a bird in a gilded cage (Toronto, 1968) and W. L. Gordon in A political memoir (Toronto, 1977). P. [J. J.] Martin is more balanced in A very public life (2v., Ottawa, 1983-85), as are J. W. Pickersgill’s Seeing Canada whole: a memoir (Markham, Ont., 1994), M. [W.] Sharp’s Which reminds me . . . : a memoir (Toronto, 1994), and Trudeau’s Memoirs (Toronto, 1993).

There are numerous works that touch upon the varied aspects of Pearson’s career. Among the most important are Denis Smith, Rogue Tory: the life and legend of John G. Diefenbaker (Toronto, 1995), and several works by J. L. Granatstein: A man of influence: Norman A. Robertson and Canadian statecraft, 1929-68 (Ottawa, 1981), The Ottawa men: the civil service mandarins, 1935-1957 (Toronto, 1982), and Canada, 1957-1967: the years of uncertainty and innovation (Toronto, 1986). Two more specialized works also merit attention: Stephen Azzi, Walter Gordon and the rise of Canadian nationalism (Montreal, 1999), and Greg Donaghy, Tolerant allies: Canada and the United States, 1963-1968 (Montreal, 2002). Finally, the centenary of Pearson’s birth brought forth an excellent compilation, Pearson: the unlikely gladiator, ed. Norman Hillmer (Montreal, 1999).

Among the other sources consulted are: Canada, House of Commons, Debates (Ottawa), 1948-68; D. G. Creighton, The forked road: Canada, 1939-1957 (Toronto, 1976); Douglas Fisher, “A personal view: the quick, unusual hallowing of Lester B. Pearson,” Executive ([Don Mills, Ont.]), 15 (1973), nos.7/8: 54; H. L. Keenleyside, Memoirs (2v., Toronto, 1981-82); J. R. Matheson, Canada’s flag: a search for a country (Boston, 1980); Denis Smith, Diplomacy of fear: Canada and the Cold War, 1941-1948 (Toronto, 1988); and Reginald Whitaker and Gary Marcuse, Cold War Canada: the making of a national insecurity state, 1945-1957 (Toronto, 1994).

Cite This Article

John English, “PEARSON, LESTER BOWLES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 20, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/pearson_lester_bowles_20E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/pearson_lester_bowles_20E.html |

| Author of Article: | John English |

| Title of Article: | PEARSON, LESTER BOWLES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 20 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2016 |

| Access Date: | March 28, 2025 |