As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

Source: Link

TRENHOLME, CLEMENTINA (Fessenden), imperialist and author; b. 4 May 1843 in Kingsey Township, Lower Canada, daughter of Edward Trenholm and Mary Ann Ridley; m. 4 Jan. 1865 Elisha Joseph Fessenden, and they had four sons, including Reginald Aubrey*; d. 14 Sept. 1918 in Hamilton, Ont.

Clementina Trenholme’s father had emigrated from Yorkshire, England, and her mother had come from Ireland. Trenholme was the fourth of 12 children in a household that fostered a passion for loyalism and British tradition. Through tales of how they had sheltered British troops during the rebellion of 1837–38, her parents showed her that convictions should be reflected in action.

Clementina was educated at the school and high school in the village of Trenholm, and then at Miss Loy’s Seminary in Montreal. Following her marriage to Anglican priest Joseph Fessenden, the couple lived in East Bolton, Lower Canada, in Fergus, Ont., and, from 1879, in Chippawa, where Trenholme raised her children and served as editor of the Niagara Woman’s Auxiliary Leaflet. In 1895 her husband became rector at Ancaster, and Trenholme continued her interest in church-related activities and writing there. She contributed to the Ontario Churchwoman, edited the Niagara Leaflet of the West, and petitioned successfully to have the ascription restored in the prayer-book used by the Woman’s Auxiliary of the Anglican church.

The approach of Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee (1897) intensified the concern of both Trenholme and her husband about Canada’s ties to the British empire. Alarmed by the prospect of a diminishing sense of British heritage in Canada, she viewed non-British immigration and lingering continentalist ideas [see Erastus Wiman*] as threats that had to be averted. She began to devise plans to make the British presence a permanent facet of Canadian life. Having started to identify herself with the image of the queen, Trenholme often dressed like her and was pleased when the resemblance was noticed. With this focus on history and nationalism, she joined the League of the Empire, the Brome County Historical Society in Quebec, and the Wentworth Historical Society, of which she was recording secretary.

In 1896, in the midst of organizing support for a flag day, her husband died, and Trenholme’s efforts took on the overtones of a providential mission. She sold all her household possessions to raise money, moved to Hamilton, and in 1897 mounted a vigorous public campaign to combine imperialism, patriotism, and education through the establishment of an empire day in Canada’s schools. The idea had come to her as she witnessed the enthusiasm of her granddaughter on being made an honorary member of the Wentworth Historical Society. It had been, Trenholme said, “the imperial spirit which, through the guiding hand of a child, led the way for me.” Though faced with opposition and indifference, she spoke at meetings, wrote articles, made presentations to the Hamilton Board of Education, and gained the support of Ontario’s sympathetic minister of education, George William Ross. She also tried to enlist the backing of Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier, a friend of her brother Norman William, a Montreal lawyer, but he politely responded that he had “made it a rule, long ago, not to interfere in educational matters,” which were outside federal jurisdiction. Nevertheless, Trenholme’s scheme found wide acceptance and Empire Day was first observed in 1898 at Dundas, Ont., on the last school day before 24 May (the queen’s birthday).

During the South African War and the years of imperial fervour that followed, Trenholme discovered new outlets for her promotion of a greater Canada within the empire. In 1900 she was the founding secretary of the first Hamilton chapter of the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire, known as the Fessenden Chapter. The next year it purchased new colours for the 13th Regiment, members of which had served in the war, and Trenholme read the chapter’s address to the visiting Duke of Cornwall. She was made a councillor of the League of the Empire in 1903 and seven years later the imperial cadet authorities named a rifle contest and its prize in her honour.

When patriotic values took symbolic form, Trenholme could be a relentless agitator. She was fanatically anti-American, and the presence of the Stars and Stripes anywhere in Canada – whether at circuses, cottages, or exhibitions – drew her ire. For eight years after the publication of her pamphlet Our Union Jack (1898), she tried unsuccessfully, through the Ontario Historical Society’s flag committee and other means, to persuade the boards of education of Toronto and elsewhere to purchase a chart she had had printed showing the British heritage of the Canadian Red Ensign. In 1900 she began her two-year curatorship of Dundurn Castle, after she had appeared before a meeting of Hamilton’s aldermen to ask that the one-time mansion of Sir Allan Napier MacNab* be preserved as a museum. Often she spoke through a barrage of letters, usually to the newspapers, and she occasionally resorted to direct confrontation. In 1902 she added her protest to that of the OHS to block plans for a monument to American major-general Richard Montgomery* in Quebec City. To press her case she tracked down a government official in Maine, who observed with exasperation that she had “rather novel ways of finding out things – as I am in Maine on personal matters.” Immediately after the Montgomery affair she and William Kirby* launched a campaign to persuade the bishop of London to abandon the idea of a monument to George Washington in St Paul’s Cathedral, a project that would not finally be given up until 1913. On behalf of the Wentworth County Veterans’ Association, she raised money and public support for a monument commemorating the graves of soldiers who had died in the battle of Stoney Creek (1813) and attended its unveiling on 1 Aug. 1910. She also ran a ceaseless campaign to have herself legally recognized as the founder of Empire Day, with an annuity from the dominion government, and she defended her claim in 1910 in The genesis of Empire Day.

A member of both the Women’s Institute and the National Council of Women of Canada, by 1913 Trenholme had turned her attention to the much-discussed issue of women’s suffrage, which she vociferously opposed. Speaking through a series of newspaper letters, she described votes for women as an empty promise of power since only men were in positions to enforce legislation. The women’s movement was acceptable, in so far as it strengthened women’s influences within the domestic sphere, but suffragism, she wrote in the Hamilton Spectator in 1913, “was just the thin edge of the wedge, opening the door to the inner room of socialism, agnosticism, anarchy, feminism, each and all making for the ‘dismemberment of the Empire.’”

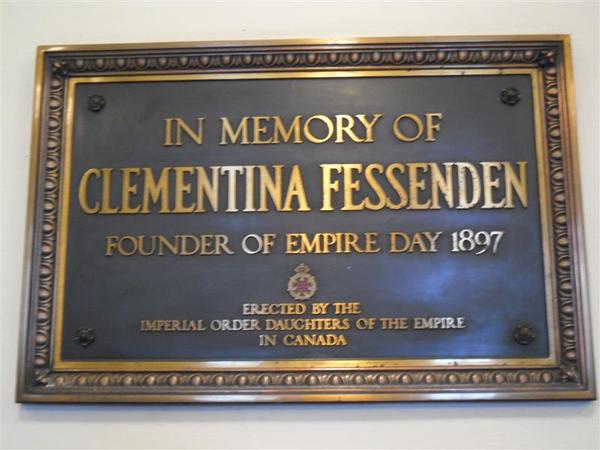

During World War I Trenholme worked on the Belgian Relief Committee in Hamilton. In 1915 she opposed the efforts of the Women’s Peace Party, headed by Jane Addams of Chicago, by circulating an anti-peace petition calling for total victory over Germany. Two months before the armistice she died, at the age of 74. For some years after her death the IODE held Empire Day services at her grave-site at St John’s Anglican Church in Ancaster, and in 1928 the order installed a commemorative plaque there.

Clementina Trenholme Fessenden, who frequently visited her son Reginald in Massachusetts, wrote a series of columns entitled “Breezy bits from Boston,” which appeared in the Hamilton Spectator between July 1908 and March 1909.

ANQ-E, CE1-45, 25 janv. 1844. AO, RG 22-205, no.4136. HPL, Arch. files, Canadian Club papers; Clipping files, Mabel Burkholder, “Essays on Ontario’s history,” vol. 1 (1944), Hamilton biog., and Hamilton – organizations and societies – IODE; Scrapbooks, Battle of Stoney Creek, H. F. Gardiner, vols.90, 274, and St John’s Anglican Church, Ancaster, vol.1. Niagara Hist. Soc. Museum (Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ont.), H.IV (Clementina Fessenden papers) (mfm. at AO, F 1138). Hamilton Spectator, 1909-10, 1913, 1918. J. S. Belrose, “Fessenden and the birth of radio communication” (unpublished paper, Ottawa, 1991; copy in possession of the contributor). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). DHB, vol.3. The Hamilton centennial, 1846–1946, ed. A. H. Wingfield ([Hamilton, Ont.], 1946). Gerald Killan, Preserving Ontario’s heritage: a history of the Ontario Historical Society (Ottawa, 1976). R. M. Stamp, “Empire Day in the schools of Ontario: the training of young imperialists,” JCS, 8 (1973), no.3: 32–42. J. B. Wray, “One hundred and twenty-six years of arrangements by Blaford and Wray,” Wentworth Bygones (Hamilton), no.8 (1969): 64.

Cite This Article

Molly Pulver Ungar, “TRENHOLME, CLEMENTINA (Fessenden),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/trenholme_clementina_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/trenholme_clementina_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Molly Pulver Ungar |

| Title of Article: | TRENHOLME, CLEMENTINA (Fessenden) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | March 29, 2025 |