As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

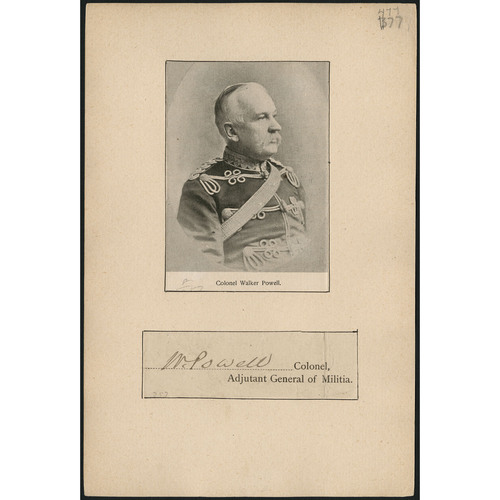

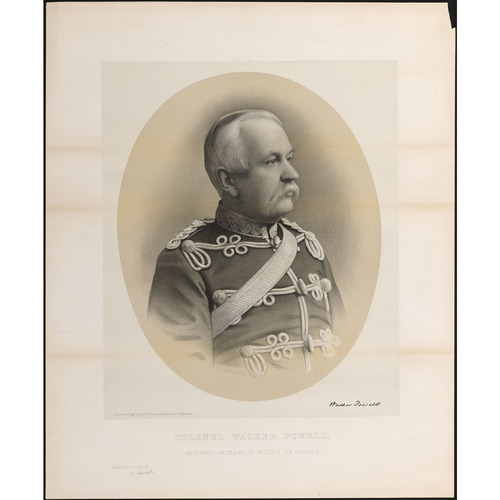

POWELL, WALKER, office holder, businessman, politician, and militia officer; b. 20 May 1828 in Waterford, Upper Canada, son of Israel Wood Powell, a merchant, and Melinda Boss; brother of Israel Wood Powell; m. first 18 April 1853 Catherine Emma Culver (d. 1855) in Woodhouse Township, Upper Canada, and they had one daughter; m. secondly 12 Oct. 1857 Mary Ursula Bowlby, and they had five children, four of whom lived to adulthood; d. 6 May 1915 in Ottawa.

Walker Powell was educated at the Norfolk County grammar school and at Victoria College, Cobourg, and returned home to share the family’s intense involvement in local and county life. The population of Port Dover, where they had moved, grew 50 per cent in the six years after the Reciprocity Treaty of 1854, and Powell grew with it. He had wealth and influence enough for public life. Beginning as a trustee of the county grammar school, he progressed to chair the united board of the grammar and public schools and served seven years on the Norfolk County Council, ending as warden in 1856. From 1847 Powell had also been an officer in the militia, becoming adjutant of the 1st Regiment of Norfolk. By 1858 he was town reeve, commissioner for the Court of Queen’s Bench, agent for two insurance companies, and head of I. W. Powell and Sons, shipping agents. His shipping and trading interests made him a moderate Reformer, and his county elected him to parliament in 1857.

In 1861 the Trent affair [see Sir Charles Hastings Doyle*], with its threat of war with the United States, forced the pace of militia reform, and Powell became deeply involved. By 1862, when Attorney General John A. Macdonald* of Upper Canada proposed a scheme based on compulsory training, British reinforcements had arrived and the crisis had cooled. A host of factors, including angry militia officers, defeated the militia reforms and the government and brought the Reformers under John Sandfïeld Macdonald* to power. Powell, who had lost his seat in 1861 and whose personal affairs may have been in serious disorder, won the post of deputy adjutant general for Upper Canada on 19 Aug. 1862. In 1868, after confederation, his political past was forgotten: Sir George-Étienne Cartier*, the new dominion’s minister of militia, promoted him to be the sole deputy adjutant general, with a salary of $2,800. Five years later, when the adjutant general, Colonel Patrick Robertson-Ross*, resigned, Powell was promoted colonel and filled his place, and when a British officer, Major-General Edward Selby Smyth, was appointed in 1875 to command the militia, his Canadian subordinate was confirmed in the post and received an increase in salary to $3,200.

A politically astute businessman was not a bad choice. Powell needed business habits to cope with masses of routine paperwork and political astuteness to keep him out of the militia squabbles. In 1862 the Toronto Globe insisted that the militia could be made efficient without any great amount of expenditure: this aim became a bipartisan policy which Powell upheld for the rest of his long career. As the militia’s senior Canadian officer, Powell possessed no special knowledge of military affairs, but he had a capacious institutional memory and a reassuring Canadian presence amidst a succession of British generals with rigid opinions about discipline, efficiency, and proper channels. When the generals dismissed Canadian officers as ignorant colonials, men like Lieutenant-Colonel George Taylor Denison* could find a sympathetic reception from Powell. In his intervals as acting head of the militia, Powell provided discreet and realistic advice to those who consulted him. He discouraged the recurrent campaigns to allow the British army to recruit in Canada, understood that Canada’s security was enhanced if the United States did not feel threatened, and recognized that military preparedness was not a developing country’s top priority. In his words, “Where the energies of the population are so largely needed in the prosecution of the ordinary pursuits, it is indispensable that any provision for the defence made by Canada should be . . . of such nature as to cause the greatest good to result from the least expenditure.”

As an Ottawa administrator, Powell had little direct influence on militia policy, but politicians on both sides of the House of Commons trusted him. In 1874 he persuaded Alexander Mackenzie*’s Liberal government to adopt Kingston, Ont., as the site for a new military college [see Edward Osborne Hewett*], though it was in Sir John A. Macdonald’s riding, and he supported making the institution more like a Canadian university and less like its American exemplar, the United States Military Academy at West Point, N.Y.

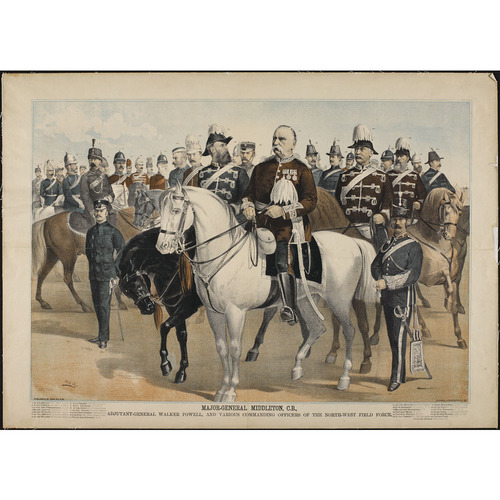

In the Red River expedition of 1870, and again during the 1885 campaign in the North-West Territories, when his British superior, Frederick Dobson Middleton*, was absent on active service, Powell carried the huge administrative burden of maintaining a militia army in the field without expanding his tiny staff. Middleton recommended Powell for a cmg, but awards of honours were scrapped when Sir Adolphe-Philippe Caron*, the minister of militia, recognized that no list would satisfy all who expected recognition. Powell’s only reward was to be sent on an official mission to Hawaii in 1887.

Powell’s influence as the sole staff officer at militia headquarters was challenged in the 1890s with the advent of Major-General Ivor John Caradoc Herbert* and an era of militia reform. Herbert clashed repeatedly with the elderly adjutant general. Matters reached a climax in 1894, when, without Herbert’s authority, Powell published the minister’s directive to suspend summer militia camps as the price of buying new rifles. Herbert accused him of insubordination, suspended him, and locked his office. Herbert’s action provoked a storm of protest. The Canadian Military Gazette (Montreal), an organ for militia officers, proclaimed Powell “the most valuable officer connected with the volunteer force throughout the Dominion.” An embarrassed minister quickly reinstated Powell and tried to defend his general: “The work of the militia is not a camping-out like a Knights of Pythias expedition.” For a variety of reasons, it was Herbert who left the following year.

On 31 Dec. 1895 Powell retired. He lived on in Ottawa, enjoying the Rideau Club, where he had been president in 1893. On 6 May 1915 he finally died, very old and forgotten save by two surviving daughters and a son.

NA, MG 26, A: 39747; MG 29, E28; E29, 1: 559; 3. Can., House of Commons, Debates, 17 July 1894. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.1. Directory, Can., Prov. of, 1851, 1854, 1857/58. Desmond Morton, Ministers and generals: politics and the Canadian militia, 1868–1904 (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1970). Norfolk County marriage records, 1795–1870, ed. W. R. Yeager (mimeograph, Simcoe, Ont., 1979), 146, 155. R. A. Preston, Canada and “Imperial Defense”; a study of the origins of the British Commonwealth’s defense organization, 1867–1919 (Toronto and Durham, N.C., 1967), 145–46; Canada’s RMC: a history of the Royal Military College (Toronto, 1969). C. P. Stacey, Canada and the British army, 1846–1871: a study in the practice of responsible government (rev. ed., Toronto, 1963), 136. Wallace, Macmillan dict.

Cite This Article

Desmond Morton, “POWELL, WALKER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/powell_walker_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/powell_walker_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Desmond Morton |

| Title of Article: | POWELL, WALKER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | March 29, 2025 |