As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

Source: Link

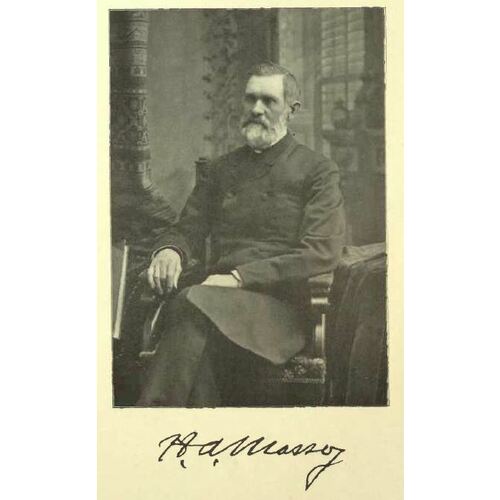

MASSEY, HART ALMERRIN, businessman, office holder, jp, and philanthropist; b. 29 April 1823 in Haldimand Township, Upper Canada, eldest son of Daniel Massey* and Lucina Bradley; m. 10 June 1847 Eliza Ann Phelps in Gloversville, N.Y., and they had five sons, one of whom died in infancy, and a daughter; d. 20 Feb. 1896 in Toronto.

Born on his father’s farm in Northumberland County, Hart Almerrin Massey was educated locally and at Watertown, N.Y., where he had relatives; between 1842 and 1846 he attended three sessions at Victoria College, Cobourg. An experienced teamster and farmer, he was given title to the homestead in January 1847, the year Daniel Massey opened a foundry near Newcastle. Five months later Hart married a young American girl whose Methodist Episcopal upbringing complemented his own devout Methodism (he had undergone conversion at age 15). They settled in Haldimand, where Massey came to notice as a school trustee, magistrate, and member of the local reform association.

In 1851 he moved to Newcastle, becoming superintendent of his father’s works, and two years later, on 17 January, they formed a partnership, H. A. Massey and Company. By the late 1840s mechanization of agriculture had spread from the northeastern United States into Upper Canada, where the production of implements would be nurtured by protective tariffs, and patent legislation. Between 1851 and 1861 Hart, following rapid American technological developments with calculated interest, returned from trips to New York state with a series of production rights – for a mower, a reaper, a combined reaper and mower, and then a self-raking reaper – that were to enhance the reputation of the Massey foundry. At the provincial agricultural exhibition in October 1855 its implements garnered prizes. In February 1856, nine months before Daniel’s death, the partnership was dissolved. Hart became sole proprietor of the business with Daniel’s strong financial backing in the form of interest-free notes totalling £3,475. Under Hart’s aggressive direction, the foundry flourished.

Having established an excellent credit rating, Massey enlarged the Newcastle works in 1857. An advertisement in the Newcastle Recorder listed a broad range of products, including steam-engines, lathes, stoves, tinware, and a combined mower and reaper “with Massey’s improvements.” It characteristically boasted that the firm could “compete with any establishment of a similar kind in Canada or the United States.” Hart apparently did worry, however, about the dumping of implements in the province by American manufacturers during the economic recession of 1857 and he shared that concern at a meeting in Toronto for the promotion of Canadian industry. As a result of the tariff increases of 1857–58 [see William Cayley*], American competitors were virtually excluded.

In 1861 some 31 factories (mostly foundries) in Upper Canada were producing agricultural implements worth more than $454,000 annually. Contributing factors were the ready adoption of mechanical harvesting devices by farmers (beginning apparently in Northumberland and Durham counties), a scarcity of farm labour, increases in wheat production, completion of railways, and further reduction of American competition because of the Civil War. Massey recognized the potential, but his firm’s output of implements was valued in the 1861 census at only $2,000 and, as in most other factories, those implements still constituted a small segment of Massey’s output. Greater annual production of implements was recorded for Massey’s major competitors: Luther Demock Sawyer and P. T. Sawyer of Hamilton, Alanson Harris of Beamsville, Joseph Hall of Oshawa, Peter Patterson of Vaughan Township, William Henry Verity of Francistown (Exeter), and Ebenezer Frost and Alexander Wood of Smiths Falls. But only Hall had invested more in his works than Massey and only a few reported any concentrated production of mowers and reapers. In this line Massey would climb.

During the 1850s and early 1860s Massey consolidated his standing as an excellent business manager, developing sound networks of supply and distribution and the means for expansion. In 1861, a key year, he obtained the rights to produce a mower and a self-raking reaper invented by Walter Abbott Wood of New York. He immediately put these acclaimed machines into production and boldly presented them to the province’s farming community. Having grasped early the need for advertising, Massey took steps during the winter of 1861–62 to publish his first profusely illustrated catalogue, using American graphics. It showed the medal awarded for his threshing machines in 1860 by the Board of Arts and Manufactures of Lower Canada. The prominent reference to successful field trials and prizes, much coveted by Massey for mass publicity, became a standard feature of his sales literature. In March 1864 fire destroyed the Newcastle works, forcing Massey to assume a $13,500 loss, but the plant was soon rebuilt to meet a stream of orders for implements. Other products were dropped. In 1867 his combined reaper and mower, sent by the Board of Agriculture of Upper Canada to the international exposition in France, won a medal, with Massey present to commence promotion. His first European orders followed. That year he brought into the business his 19-year-old son Charles Albert, a graduate of the British American Commercial College in Toronto who shared his father’s entrepreneurial flair.

Rising also was Massey’s prominence in Newcastle. For the local Methodist congregation he helped erect a new church and served as Sunday school superintendent. He continued to act as a magistrate, and in 1861 was appointed coroner of the United Counties of Northumberland and Durham. A freemason, he joined Durham Lodge No.66 in 1866, becoming a master mason 11 years later. He also became head of the Newcastle Woollen Manufacturing Company.

Such was Massey’s commercial success that in September 1870 he took steps (effective in January) to have his company incorporated as a joint-stock firm, the Massey Manufacturing Company, with a capital of $50,000. Hart was president and Charles vice-president and superintendent, clearly his father’s successor. In September 1871 Charles was left in charge when the Masseys, apparently because of Hart’s ill health, moved to Cleveland, Ohio. Chester Daniel, the sickly second son, engrossed in Methodist activity, saw in the move “God’s guiding hand to bring Father under better influences . . . and for the spiritual general good of our whole family.” Massey meant to enjoy his semi-retirement: in 1874 he built a “princely mansion” on Euclid Avenue at the edge of the city. Shocked, Chester soon accepted it: “Father said he wouldn’t live on any other street.”

The Masseys remained in Cleveland until 1882. Hart took well to life there and in 1876 became an American citizen. Politically, his reform interests may have become Democratic leanings, but that is uncertain, for the family admired Republican presidents Ulysses S. Grant and Rutherford Birchard Hayes. He travelled a great deal, touring the southern states a number of times, once in 1873 with the Reverend William Morley Punshon*. Soon after the move, Hart, his daughter, Lillian Frances*, and Chester had entered Ohio’s Methodist community; Hart was particularly active in the erection of churches, sabbath school affairs, camp meetings, and conferences. As president of the trustees of First Methodist Episcopal Church, he sanctioned a typically Methodist set of “General Rules,” drafted by Chester. Those prohibiting “laying up treasure upon earth” and borrowing money or “taking up goods” without the “probability of paying” give point to the family’s evolving philosophy of philanthropy and its reconciliation of wealth and faith.

During these years Massey became imbued with the evangelicalism of the Methodist Episcopal Church. He early embraced the principles of the Chautauqua Assembly, established at Chautauqua Lake, N.Y., in 1874 by Lewis Miller, another manufacturer of agricultural implements, and Methodist Episcopal clergyman John Heyl Vincent, whose stepsister would marry Chester. Organized as a popular religious-educational movement in a camp setting, the assembly also became for many rich Methodists a summer resort. Massey, a trustee, had a tent and in 1880 he erected a “fine cottage of the Swiss style of architecture.”

Not surprisingly, Massey was drawn into business in Cleveland, with mediocre results. He was president of the Empire Coal Company (1873–74) and the Cleveland Coal Company (1876–77), and he invested in residential real estate. His combined undertakings left him, when he returned to Ontario, with little more than worked-out mines, problems of realty management, and an unshakeable reputation for “being little and mean,” as one Cleveland lawyer later put it. Still, he had no reason to worry. As a result of Charles’s bullish management and relentless publicity (notably with catalogues and Massey’s Pictorial, a tabloid begun in 1875), the Newcastle works had continued to prosper. In 1874 the tariff on implements had been raised to 17.5 per cent and in 1879, under the Conservative government’s National Policy, it would go to 25 per cent. In 1876 Charles could assure a parliamentary committee that the tariff level was satisfactory. During the current depression the business, an agent for R. G. Dun and Company reported, was “going on in a very careful way & not pushing trade.” In 1878 it introduced the Massey harvester, “the first machine of wholly Canadian design.” Instant success created unprecedented demand, which, with the bounty from the tariff increase, enabled a major expansion and relocation.

Hart appears to have begun foresightedly accumulating land in Toronto as early as 1872. Negotiations initiated by Charles in September 1878 to acquire much of the Ordnance reserve block on King Street, near railway lines, were easily concluded the following spring. His father came to Toronto to superintend the construction of works. Production resumed that fall. In Cleveland or Toronto, Hart participated in or advised on developments between 1879 and 1884 that significantly affected the company. In the fall of 1879 the Ontario Agricultural Implement Manufacturers’ Association was formed, a means by which the Masseys and other producers, notably A. Harris, Son and Company of Brantford [see John Harris*], could control prices and output. The refinement of self-knotting devices for binding grain had an enormous impact. In 1879 the Masseys purchased their first model for a self-binder from Aultman, Miller and Company of Ohio. Their acquisition of the Toronto Reaper and Mower Company in September 1881, and of its patent rights, led them in 1882–83 into the purchase of further American prototypes, field trials, and the production of a lucrative line of binders. Purchase of manufacturing and sales rights for at least one American machine was arranged by Hart Massey and Lewis Miller at Chautauqua in August 1882.

Because of their binders, both the Massey and the Harris firms achieved extraordinary sales during the 1880s. In the summer of 1881, to capitalize on Manitoba’s promise as a major grain producer, the Masseys opened a branch in Winnipeg managed by Thomas James McBride. In Toronto their newly organized department for popular advertising used lithographic illustration to promote the Massey brand name by such means as idyllic depictions of the “model Canadian farmer who patronizes the Massey Mfg. Co.” In 1881–82 the Massey works was enlarged and in January 1882 Chester came to Toronto to begin Massey’s Illustrated, an advertising handout that would become a periodical directed at rural subscribers.

Anticipating direct involvement with the growing firm, Hart moved to Toronto in the summer of 1882, purchasing a property on Jarvis Street later named Euclid Hall. That fall he was struck by an illness falsely diagnosed as terminal stomach cancer. “We passed through great sorrow,” Chester confessed in his diary. In December the family joined the cathedral of Methodism in Canada, Metropolitan Church. By early January Massey was able “to devote his whole attention” to the complex business Charles had shaped so efficiently. Politically he had found it commercially expedient to adopt both the Conservative party and its protectionist policy.

The three Masseys were a potent combination in Canadian manufacturing, a team that participated vigorously in the cut-throat competition of the implement industry. An increase in the tariff to 35 per cent in 1883 served not only to solidify the position of delighted Canadian manufacturers but to intensify the so-called binder war between the Massey and Harris firms. In June and July 1883, the Massey company sent some 19 flag-decked box-cars of machines to Manitoba via the United States, “the largest solid freight train from any single manufacturing firm” to leave Canada, one newspaper claimed. In bitter contrast, Charles’s sudden death from typhoid on 12 Feb. 1884 hit his father hard, leaving him with the deep persuasion that the family should never be forgotten by the public and the realization that the company was his responsibility again. A hall was opened at the works in December in memory of Charles for workers’ concerts, readings, meetings, and later a sabbath school. Publication by Massey of a memorial sketch of Charles and a collection of sermons and condolences illustrates his propensity to aggrandize his family in the public eye. Still, through the mid 1880s Massey received sympathetic treatment in newspapers throughout the dominion.

From the time he resumed control, at 61, Massey dominated his firm in a paternal, calmly aggressive fashion, taking advice only from a few valued employees and company officials, among them his sons. He planned methodically to tighten his control of the company and ensure its growth. In 1884, against the wishes of other shareholders, and again in 1885, he increased the company’s capital stock, a necessary step, he explained, in order to be able to build warehouses in Montreal and Winnipeg, carry a large inventory of binder twine (indispensable for mechanized harvesting), and accommodate the slow collection of debts from farmers on machinery. The firm could thus “avoid borrowing,” something he rarely did. Privately he manoeuvred without sentiment to acquire company assets, wresting a large portion of stock from a company officer and some even from Charles Massey’s estate. In March 1887, when stock was again increased, Chester recorded that Massey had succeeded in purchasing “all the stock . . . held by parties outside our family.”

The Canadian binder market was now largely controlled by Massey and Harris: in 1884 Massey sold 2,500 in Ontario, Harris 1,700, and Patterson 500. In 1885, professing great confidence in the northwest despite the North-West rebellion [see Louis Riel*], Massey sent another much-publicized freight train to Manitoba, with 240 “Famous Toronto Light Binders.” A Globe advertisement proclaimed: “Riel! Poundmaker! Big Bear! Clear the Track, Implements of Peace to Supplant those of War.” Western farmers, however, would become synonymous for Massey with difficulty in collecting; in July he was one of a delegation to Sir John A. Macdonald from the boards of trade of Toronto, Montreal, Winnipeg, and Hamilton urging disallowance of the Manitoba act exempting property under certain values from seizure. In 1886 a Massey agency was set up in Montreal and by May 1887 the Maritimes and British Columbia also had agencies. In Ontario, Massey’s membership in the Binder Manufacturer’s Association scarcely hid his part in efforts to control the market in binder twine. Working through a tractable minister of customs, Mackenzie Bowell*, Massey laboured to secure reduced duties on imported sheet steel, elimination of duties on some parts, and especially, when the firm began selling abroad, an increase in drawbacks (the refund of duties on parts or materials used in machines made for export).

The depth of Massey’s control of his company was sounded in 1886. His Toronto works, employing some 700 workers, was easily the city’s largest factory. He had never experienced organized industrial unrest. By quietly rewarding long-time service, encouraging technological innovation by employees, or doffing his black suit-coat to appear in group photographs, Massey had cultivated close association with his men. Indeed, his genuine and sometimes progressive interest in them and his notions of popular education – the sort he knew from Cleveland and Chautauqua – can be seen in the creation of a reading-room (and with it the Workman’s Library Association), a band, a mutual benefit society, and, in 1885, an in-house workingman’s newspaper, the Trip Hammer. Nevertheless, in 1883 complaints over wage reductions had emerged through Maple Leaf Assembly 2622 of the Knights of Labor. In February 1886 some 400 workers peacefully struck over wages and Massey’s dismissal of five members of the local. Here he was supporting the plant superintendent, William F. Johnston, whose long service and technical contribution to the firm’s patents had earned him a solid place. The Knights’ leader, Daniel John O’Donoghue*, described Massey as a “brute . . . devoid of soul.” Massey was unnerved by the Knights’ “unwarranted interference.” A hastily distributed circular brought him promises of support from implement producers throughout the province. However, faced by solidarity among the workers, the intervention of Mayor William Holmes Howland, and the decision on day three by the highly skilled tool-room to join the strike, an embarrassed Massey conceded on day five. Saving face where he could, he took steps to repair labour relations (he opposed the “eight-hour” movement that spring on the grounds that workers would not be able to make ends meet) and to restore the operating efficiency that was vital to his plans for the company in 1886.

In his report to stockholders in April 1886, Massey lamented the “labour question” and also the “continued financial embarrassment of the country,” especially pronounced on the Prairies where agriculture was proving to be uneconomic. For him, the solution to the company’s problems, including the war with the Harris firm, lay in expansion, not further into western Canada – “that Lone Land” he called it – but into foreign trade. With its large capacity the firm could “make nearly twice the number of machines that our Canadian trade would demand.” This capacity, combined with demands for labour-saving implements from other grain-growing countries and the continuation of drawbacks, enabled Massey to counter Canada’s shorter seasons and greater transportation costs and its emerging agrarian backlash against the high costs of tariff-protected machinery by entering overseas markets, one of the first North American producers to do so.

By March 1887 Massey had selected his second cousin Frederick Isaiah Massey, vice-president of the Iowa Iron Works and head of a firm of commission merchants in Chicago, as manager for Britain and Europe. He himself had prepared the ground, by attending the Colonial and Indian Exhibition in London in August 1886 to measure the competitive strength of his “Toronto Light Binder.” This and other machines won medals and pre-arranged sales produced useful testimonials, from among others former governor general Lord Lorne [Campbell*] and later from Lord Lansdowne [Petty-Fitzmaurice*]. In early 1887 Massey took steps to open a branch in Argentina. That year 24 binders were sent to Australia on speculation; by May 1888 Walter Edward Hart Massey*, who had joined the firm after Charles’s death, was chastising his father for delays in shipping machines to London and Australia, where field trials in 1889 confirmed their superiority – or so the Masseys claimed – over those of the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company in the United States and others.

The response in Canada to Massey’s international success was highly favourable. The press viewed it in terms of national well-being, a point he too never failed to make. Moreover, returning from the London exhibition, he had a euphoric welcome from his workers, whom he credited for the company’s success at the “Colonial” and to whom he promised fair treatment. “This is a very great change in the last 8 months,” the Canadian Labor Reformer observed.

Much of Massey’s prominence in the 1880s was based unarguably on his entrepreneurial ability and on the managerial core he developed after Charles’s death. His interests in international expansion and drawbacks suggest a totally pragmatic grasp of the National Policy and the limits of the Canadian market. At the same time he made every effort to exploit the protected industrial environment in which the firm operated and was ever mindful of its political origin. In September 1887 Sir John A. Macdonald, who was being pressed on protection, exhorted Massey to buy into a “first class newspaper” in order to voice his opposition to commercial union with the United States and unrestricted reciprocity. Four months later, in a mood of “crisis,” the prime minister invited Massey and other supporters to meet with him to consider “energetic steps” for maintenance of the National Policy. However, a discerning interview with Massey on the tariff, in the Toronto Daily Mail of 13 Feb. 1888, reveals he had grievances despite protection: high duties on imported steel and iron (the cost advantages of British supplies had long disappeared and Massey now bought in Ohio and Pennsylvania), the need for more rolling mills in Canada, political favouritism towards Nova Scotia’s budding steel industry, from which he also bought, and his professed difficulties in getting rebates on exported machinery. Claiming smugly, and with some political ambiguity, that he could compete effectively against American producers in an open market of commercial union, Massey meanwhile pushed for the removal of duties on imported materials. Such elimination, he told the Mail, bluntly linking his business and national prosperity, was vital in “fostering” the foreign market needed by Canadian manufacturers. In 1888–89 he continued to negotiate with Bowell over the removal of duties on parts, and in March 1888 he met with finance minister Sir Charles Tupper* to discuss both the reduction of duties on iron and the “enormous taxation on agricultural implements.”

In Toronto Hart had been moving to increase operating efficiencies. A printing department was started in 1886 under Walter, then the company’s creative secretary-treasurer. The Masseys’ flair for advertising and mass appeal is evident in their use of cartoons, colour, and grass-roots humour: the product lines for 1887 were labelled “Bee-Line Machines” and on delivery days in rural Ontario, farmers were given the hard sell at receptions featuring “crushed drive wheels on toast,” “crank shaft pie,” and other mechanical delights. However, in 1888–89, he failed in an attempt to gain control of and move the Hamilton Iron Forging Company, a supplier and Ontario’s only large producer of primary shapes. In Toronto, his offer to the city to build a malleable-iron works in exchange for ten taxless years produced controversy in council as the strategy of granting such bonuses to industry became suspect.

There were other difficulties. Massey’s personal parsimony – the petty side of his business persona – was becoming as well known as his King Street factory. In 1887 the cost of treating his sick daughter while she was travelling on a Canadian Pacific Railway train in the west prompted a complaint to general manager William Cornelius Van Horne*. Accusations of “gall and nerve” drifted in. His support for such local Conservatives as Frederick Charles Denison and for the National Policy apparently failed to give Massey real standing in Ottawa (he and Macdonald were certainly incompatible personally). His recommendations in 1888 for municipal reform in Toronto – significant in terms of his later philanthropy – were ignored, in part because of his use of American models and also because his genuine interest in reducing pauperism through tax relief for the “labouring man,” subsidized lectures, and more parks and libraries was thought impractical. If Massey was dissatisfied, the Evening Telegram retorted, he should seek public office. Clearly, any goals he envisioned as he began turning his thoughts to social welfare would have to be accomplished privately. In 1888, to give shape to his dream of a major music hall in Toronto, he asked Sidney Rose Badgley, a Canadian architect in Cleveland, for the plans for that city’s hall.

A bitter controversy over the federation of Victoria College with the University of Toronto and its move from Cobourg [see Nathanael Burwash*] reveals two basic components of Massey’s last years: his philanthropy and the attendant censure of his activities. In the fall of 1888 he offered $250,000 to maintain Victoria as an independent college at Cobourg. But a series of vicious articles in the Toronto World in December, by editor William Findlay Maclean*, alleged Massey had reneged on a prior pledge of financial support for federation. Maclean claimed further, during the much-publicized libel suit filed by Massey, that the pledge had been made to such prominent Methodist leaders and federationists as Edward Hartley Dewart* and John Potts in exchange for their support in the Masseys’ “squeeze-out” of company stockholders years before. Also dragged out in the World was a suit against Massey by his Cleveland church over a subscription he had refused to honour. Obviously, wrote Maclean in stinging but legally clever ridicule, Massey had “worked the hay fork racket” on the college’s senate by swindling and embarrassing the federationists. In January 1889 a plea of justification was allowed in the courts for a trial in the next assizes.

Though sensitive to such criticism, especially when it appeared to attack his cherished agrarian background, Massey could rarely be distracted for long from his determination to dominate implement production in Canada. Carefully staged by W. F. Johnston, superintendent of the Toronto works and probably Massey’s best operator, field trials in July 1889 at the Paris exposition produced awards, which Massey tried to build on through a vainglorious but unsuccessful effort to secure a Legion of Honour from France and recognition of his achievements there by the Canadian government. That year, however, he did receive important confirmation by a committee of the Privy Council of the high level of drawbacks that he wanted to claim. In the spring of 1890 Massey took over the Hamilton Agricultural Works of L. D. Sawyer and Company, forming Sawyer and Massey Company and thus adding a subsidiary strong in threshing machinery. Also that year he bought out the Sarnia Agricultural Works. In one of his few major miscalculations perhaps, Massey balked at a chance to acquire controlling interest in the Hamilton Iron Forging Company.

A Methodist in business, Massey invariably found time for religion and philanthropic endeavour. He subscribed to Metropolitan Church’s Home Missionary Society (organized in 1888 for evangelistic, mission-school, and charitable work) and to other such groups in Toronto. In May 1889 he was a delegate of the Sabbath School Association of Ontario to the international Sunday school convention in London, England. Early in 1889 John Miles Wilkinson, an audacious downtown Methodist minister, won Massey’s confidence with grandiose plans for a “People’s Tabernacle.” Daring to probe the aloof Massey, Wilkinson spurred him on in June: “I hope Mr. Massey you have not given up your intention of erecting a building that will immortalise the donor & will bring incalculable good to the present & to future generations.” The project would be given shape that winter by the illness of Frederick Victor, Hart’s beloved youngest son and a student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Boston. In January he was brought home in W. C. Van Horne’s private railway car; his death in April, like that of Charles, struck hard at Massey.

The year 1890 brought other strains. In February J. H. Hillerman, a Cleveland insurance agent and defendant in a case brought by the 66-year-old Massey, complained with much truth to Chester: “Your father seems to have a chronic notion that anyone who in any way refers to his business methods is persecuting him.” In March the libel trial involving the World opened, only to find for Maclean. By June, however, amid increasingly negative press over the alleged libel and the federation issue, Massey had left for London on a bold corporate initiative.

Locked in costly competition with the Harris firm, Massey and his sons had resolved at the end of 1889 to “sell their business to an English company.” As a first step, their British subsidiary had been formally registered and capitalized in December. An apprehensive F. I. Massey viewed the proposed sale as a “radical . . . change in business.” In May 1890 the Massey board agreed to sell the parent company “for re-capitalization under British charter” and empowered Hart to carry out negotiations. These got bogged down when a British accounting firm was unable to verify the annual profit levels claimed by Massey, whose testy refusal to pay its expenses negated his awkward efforts to revive the bid. Returning to Toronto, he was forced to beat down a moulders’ strike between October 1890 and July 1891 at his Hamilton and Toronto works. Of greater significance, the Harris firm’s revolutionary open-ended binder, capable of cutting grain of any length, had been put into production for the British market, giving it a clear lead in technology and potential foreign sales.

This lead, the sheer cost of continued competition, the loss of family on both sides, and undoubtedly Massey’s British bubble, encouraged Massey and Alanson Harris to consider merging. Though historians credit Massey with taking the initiative – he excelled in the blunt business of buy-outs and forced merger – his papers are mute on this subject. Other sources, however, including the board minutes of the two companies, reveal much. Blithely ignoring weak anti-combines legislation, the Massey and Harris groups moved quickly. By late January 1891 negotiations were under way for a combination of the Massey and Harris firms and the Consumers’ Cordage Company of Montreal [see John Fitzwilliam Stairs*]; in February the Harris board, abandoning its own interest in selling out to an “English syndicate,” accepted the Masseys’ proposal (conveyed through T. J. McBride of Winnipeg) for a merger that excluded Consumers’ Cordage; on 6 May the Massey-Harris Company was established; on 22 July it was formally incorporated. No new capital entered the firm and controlling ownership remained with the two families. The technical excellence of the Brantford firm was reflected in the placement of James Kerr Osborne as vice-president and Lyman Melvin Jones* as general manager, but Massey held the presidency and with it the largest block of shares and personal control of patents, production methods, and facilities. Between 1891 and 1895 he orchestrated amalgamations with Massey-Harris that further eliminated competition and strengthened its position in specialized lines, including ploughs, steam tractors, and threshing machines [see Jesse Oldfield Wisner]. The only major Ontario works not taken in was the factory of Frost and Wood in Smiths Falls, according to the Monetary Times in November 1891. Massey-Harris was seen as a monopoly, but because the merger had been concluded during a lingering depression, it had to face the financial consequences of several years of aggressive over-selling on credit. Moreover, in the year before the merger, the two firms had accounted for only about half of the domestic sales of large implements in Canada – small manufacturers and to a lesser extent American producers still held a share of the market – and in the decade following Massey-Harris would never capture more than 60 per cent. Between 1892 and 1895 the value of its domestic sales dropped, though there were compensations in export sales.

Massey recognized the difficulties, but old age, illness, and his diversion of interest to philanthropic endeavour would undermine his ability to deal effectively with increasingly complex problems of corporate business. In Manitoba, where Massey and Harris had sold much on credit, there was a massive load of indebtedness. Western farmers in reaction pointed to the grip of the CPR, the grain monopoly [see William Watson Ogilvie], and the protective tariff policy and its industrial offspring. Massey could look to T. J. McBride in Winnipeg for practical advice on collections, but he could never totally comprehend agrarian discontent: “People are using every means possible to vent their spite on the Massey-Harris Co. on account of its consolidation. Why they should do this when they are actually getting their machines at a lower price than they did before, seems strange to us. No doubt it rises very largely from the Patrons of Industry.” Rural newspapers throughout Ontario turned against Massey as his manufacturing and philanthropic interests were confronted by new and vocal strains of radical agrarian and social criticism. In Ottawa opinions of him had changed drastically.

In 1893 he confidently lobbied for the Senate seat left vacant by the death of Methodist businessman John Macdonald*. Massey felt entitled for reasons besides his support of the Conservative government “since 1878.” Naïvely he emphasized his ability to “control and influence more votes than any other businessman,” the need for a strong Methodist voice in government, his contribution to the welfare of Canadian farmers, and his “advancement of Canada’s industrial enterprise.” As if industrial achievement merited political reward, he proudly told Prime Minister Sir John Sparrow David Thompson: “My long experience has enabled me to systematise and put into successful operation one of the largest manufacturing industries in the world.” Indeed he had, but neither Thompson nor his finance minister, George Eulas Foster*, tolerated the ageing millionaire the way Macdonald had, and it was left to Mackenzie Bowell to tell Massey bluntly that the seat had been promised to James Cox Aikins*.

Ottawa had changed its position too on tariffs. Foster and Thompson were both mindful of western agitation for the elimination of tariffs on implements. In 1893–94, with exceptional vigour, Massey fought Foster’s much lauded reduction of tariffs on implements, formally announced in March 1894. Yet in 1893 he had welcomed the Democrats’ push in the United States to reduce tariffs as an inducement to expand southward. Newspapers picked him up: “How can he contend that he can compete with the American manufacturers in their country but not in his own?” asked the Globe in November. In truth, discerning limited growth in the Canadian market, Massey had masterfully crafted plans for the international trade of Massey-Harris. In 1894 he secured, through Bowell, an unprecedented 99 per cent drawback on materials put into machines for export and, from his own board, a mandate to establish, by August 1895, an American plant. It would facilitate production for export by having access to electricity (if near Niagara Falls), cheaper rates on iron, and better transit to the east coast.

In 1894 Massey began to falter in his direction of Massey-Harris because of his poor health and engrossing devotion to philanthropic work. By the end of 1895 his health had worsened, the result he was told of “heart disease” or “disease of mucous membrane of the colon.” At times he could attend to business, getting drawbacks “in proper shape” and lobbying on the tariff, but he became caught in a pathetic round of medical consultations and restorative trips. Walter Massey later noted that from 1894 his father, then 71, spent little time on the details of business. Much of the management shifted to him, but with tension. He was irked by the elder Massey’s involvement in petty law suits in 1895, one resulting from his repeated attempt to form a British syndicate to take over Massey-Harris (an intriguing case that also sheds light on differences in business outlooks in North America and Britain). Both Walter and F. I. Massey in London seriously questioned the commercial wisdom of Hart’s move into the production of bicycles, then a popular rage, but they indulged him in a harmless fascination with the prospect of building automobiles. Finally, in a letter in July 1895, after scolding his ailing father for tinkering with the steam launch at the family’s Muskoka camp, Walter unloaded his frustration over Hart’s procrastination on the move into the United States. “This whole matter rests with yourself. . . . Mr. McBride would be available from Winnipeg at any time to take hold of the U.S. business and is only too willing to go.”

If Massey’s competence in business had become impaired, his philanthropic vision became clearer despite close public scrutiny. During his years in the United States he had been drawn to the evolving gospel of wealth – a component of evangelical Protestantism (including Wesleyan doctrine) that held diligence in business to be a Christian duty and wealth to be a trust from God. For Massey, this belief had been reinforced at Chautauqua and through exposure to such popular evangelical revivalists as Dwight Lyman Moody of Chicago. In Toronto during the 1880s, with the Methodist church adapting to a wealthy laity and systematic benevolence growing as a means of grace, Massey received strong clerical and lay encouragement in his sober drive to fill his self-claimed role as a “steward” of God. Other Methodist businessmen, for example John Macdonald, set strong examples. A fervent temperance advocate, Massey continued to support the inner-city mission work of Metropolitan Church. In February 1893, identifying himself in a letter to John Carling* as one of its “foremost workers,” he announced his final goal: “I am preparing for the distribution of my means to the best advantage in the interests of Canada, and am desirous of doing what I can during the remainder of my days towards the advancement of these interests, and the giving of my time largely for the benefit of the public.”

Between 1891 and his death in 1896 Massey zealously supported or began an impressive array of mission and charitable initiatives, among them the Methodist Social Union of Toronto (1892), the Children’s Aid Society, the Salvation Army’s Rescue Home in Parkdale, the Methodist camp at the family’s Muskoka resort (1891), a sanatorium project with William James Gage*, and industrial training in Toronto’s schools. Popular evangelists such as D. L. Moody (whom many Methodists shunned) and the team of Hugh Thomas Crossley* and John Edwin Hunter* received Massey’s enthusiastic support. His donation of $40,000 in 1892 to endow a theological chair at Victoria College (he had eventually accepted relocation and federation) signalled the philanthropic thrust of his last years. In late 1892 he advertised for suggestions on how he could use his wealth “for the greatest good.” Patiently he sifted the responses, favouring Methodist institutions. He received in return the recognition he publicly and privately desired. In May 1895 Albert Carman*, general superintendent of the Methodist Church, close his thanks to Massey for support of Albert College, Belleville, with “Praying you be guided and strengthened in all these grand designs, and that you find satisfaction on earth and reward and glory in heaven.”

Massey’s philanthropic involvement and the public response to it are best illustrated by two well-known projects, both built under his authoritarian control. The mission hall grew out of an urban mission begun in the mid 1880s by members of Metropolitan Church (notably Mary T. Sheffield), the need of the Central Lodging House Association of Toronto for larger quarters, and Massey’s well-funded evangelical drive. By December 1892 he had made the project his own, securing sketches from noted Toronto architect Edward James Lennox* for a “Mission Hall & Men’s home” and gathering information on self-help programs from such institutions as the Industrial Association of Detroit and the Department of Charities and Corrections in Cleveland. Within months it had become identified as a memorial to Fred Victor. His typical insistence upon total involvement led to disputes with both Lennox and the builders. The mission opened in October 1894 to minister to the urban poor and to house homeless men, and was operated by the Toronto City Missionary Society, basically a management board set up by Massey. As a result of his financing and attention to detail, the mission (by contemporary standards) was an exceptional facility, with programs in five departments: evangelical (including deaconesses), industrial, educational, mercy and help, and physical activity. It and the Presbyterians’ St Andrew’s Institute, established in 1890 by Daniel James Macdonnell, were ambitious church innovations, reflecting pioneering efforts in England, Scotland, and the United States in the 1880s. The Massey mission, in the opinion of Margaret Prang, was a “new approach to old social sins in an urban setting” but it was “essentially conservative and rested on no fundamental criticism.” The only cure for idleness was still Jesus Christ. Massey rejected outright the radical social reforms espoused by American economist Henry George and others. Within months of opening, the Fred Victor Mission was attracting more men than it could accommodate, many from the “most degraded class in our community,” Massey was told. But he focused on its cleanliness and the objectionable appearance of men “lounging around on the street in front of the doors.” Ironically, he was the major early benefactor of Wesley College, Winnipeg, a vigorous source of the nascent Social Gospel that would draw inspiration from the conditions of the very farmers who had turned on him.

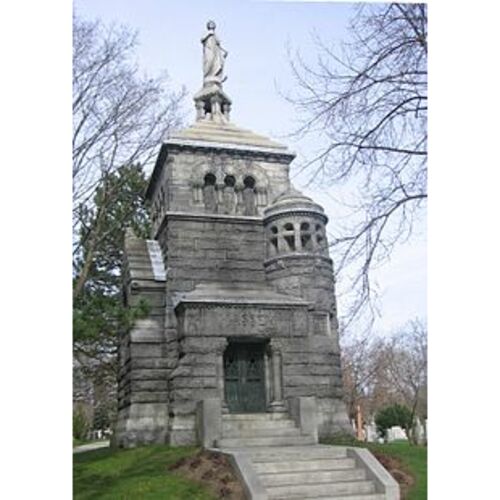

Similar patterns were evident with the music hall. Though never members of the city’s social élite, Massey and his family had long participated in its musical life, again a reflection of their Chautauqua experience. Massey bought organs for Methodist chapels, both Charles and Fred had had musical interests, and music figured in the workers’ programs at the Massey factory. As a vice-president of the reorganized Toronto Philharmonic Society in 1891, Massey knew its leader, Frederick Herbert Torrington*, organist and choirmaster at Metropolitan Church. Torrington’s achievements plus his own turn to philanthropy spurred Massey to build the grand hall that he had been contemplating as yet another memorial to Charles. Designed by S. R. Badgley and built under the supervision of Toronto architect George Martell Miller in 1893–94, Massey Music Hall opened on 14 June 1894 with a performance of the Messiah. An ailing Massey attended against his doctor’s order. Again his almost fanatical involvement produced disputes, with the builders and with Torrington, even though ownership and management had been turned over on 5 June to a board of trustees comprised of John Jacob Withrow and Chester and Walter Massey. In October, apparently during a disagreement about fees, Torrington threatened to file suit over Hart’s insinuation that he and others were attempting to “crush” him. Claiming misinterpretation and reacting perhaps to other pressures, Massey threw his generosity in building the hall in the maestro’s face. Despite Massey’s refined interest in architecture, the Canadian Architect and Builder attacked the exterior of the hall for being “about as aesthetical as the average grain elevator.” Still, it had outstanding acoustical properties and immediately became a major centre for musical and public functions; in the fall of 1894 a series of “evangelical meetings” were held there by D. L. Moody, whose waning appeal had forced Massey to defend the event.

Attitudes toward Massey became harshly polarized before his death. His wealth attracted an extraordinary volume of virulent anti-capitalist sniping, especially from the militant Patrons of Industry, who articulated agrarian discontent in Ontario and the west [see George Wesley Wrigley*]. In 1892 the Patrons’ Canada Farmers’ Sun ridiculed the motives behind Massey’s liberality and singled out his music hall: “Canada never knew the dead Massey, and it wants no public monuments erected in his name.” Two years later, Patron John Miller, speaking before the Trades and Labor Council of Toronto, condemned combines and Massey’s use of money squeezed from farmers and his own workers for “buildings such as that ‘Bummers’ Roost’ at the corner of Jarvis Street.” Massey served as a lightning-rod too for the reformist impulse in religious and social debate. His “ostentatious acts of public charity,” which many believed threatened to destroy true Christianity, were lampooned by such publications as Grip. New social definitions of Christianity emerged to challenge, on intellectual grounds, “economic inequities” and religious opiates such as that propounded by Moody, which appealed to wealthy evangelicals like Massey.

Massey resolutely followed the coverage in the press. The careful segregation of negative commentary in the scrapbooks kept by the family and the barely submerged bitterness of Massey’s sons testify to its feelings. Occasionally Massey entered the debate. To his reaction over a piece in the Ottawa Daily Free Press about the music hall, the journal retorted as others had: “Massey seems to regard the remarks . . . as reflections upon his business methods, his personal honor and his reputation as a manufacturer, but he is mistaken.” Most of the coverage of Massey was laudatory however – philanthropy could still produce rewards on earth – and of course farmers continued to buy Massey-Harris machines. Typical of institutional response to Massey’s support was a report in the Sunbeam, journal of the Ontario Ladies’ College, the Methodist school in Whitby where a feeble Massey spoke in mid 1895: “In listening to Mr. Massey one is powerfully impressed by his earnest and devoted manner . . . . He is simply the steward in whose hands God had entrusted the means of assisting in good work, and [one] hopes that his mind may rightly direct him in such matters.” At the same time, relishing his rare public appearances, at the Toronto Industrial Exhibition on “Pioneer’s Day,” at the Victoria Industrial School in Mimico (Toronto), and in other sympathetic forums, Massey took an old man’s delight in his log-cabin origins. These easily found a place in the growing number of formulaic sketches of Massey, such as that in Benjamin Fish Austin*’s Prohibition leaders of America ([St Thomas, Ont.], 1895).

Massey never left his house after January 1896 and he died on the evening of 20 February. At Massey Music Hall Haydn’s Creation was being performed under the auspices of the Trades and Labor Council; at the end the conductor announced Massey’s passing, whereupon the dead march from Handel’s Saul was reverently performed. The death brought forth an outpouring of obituaries and testimonials to his personal and industrial stature, ranging from hostile commentary to equally distorted eulogies by James Allen, pastor of Metropolitan Church. Undisputed was Massey’s key role in building the largest agricultural implements manufactory in the British empire, in which business he was quietly succeeded as president by his son Walter. The Toronto Evening Star, which could not have known of Massey’s private acts of charity, provided one of the fairer contemporary assessments of this “austere man”: “He expected and exacted a similar punctiliousness from those with whom he did business. By many this was misconstrued into harshness. His charity, splendid as it was, was not such as to make him popular. It moved always on public lines. Even in his generosity, Mr. Massey was a business man . . . . His wealth served to relieve collectively, the individual being lost sight of in the aggregate. . . . Mr. Massey’s charity, working with such stately aloofness, did not provoke that intense love and enthusiasm excited by individual acts of mercy . . . . But his was not the impulsive charity that springs from an exuberant disposition. He gave because he thought it was his duty, not because he loved much.”

Massey’s grandson Charles Vincent* recalled Massey as a “tall gaunt frock-coated figure, his features softened by a white beard, driving to church in an over-full landau behind a pair of well-chosen coach-horses with an old coloured coachman in antique garb on the box, while on the back seat he sat in supreme enjoyment with his adored grandchildren tumbling about his knees, a patriarchal figure of the old school.” Not all the grandchildren received that affection and, as Vincent privately confessed to his own sons, Massey had been “bred in a narrow faith” and consequently had “blind spots” in his character. Yet, as historian Merrill Denison* has observed, given the breadth of Massey’s achievements and the range of reaction to him over time, any narrowly focused image “fails completely to capture any of the interesting conflicts of a rich and complex personality.”

The Star correctly forecast that “Massey’s reputation as a public benefactor lies in the hands of his executors.” By his death, he had given away more than $300,000 – on the music hall, on the mission, and on Methodist institutions (mostly colleges) from New Westminster to Sackville. Under his estate (worth almost $2,200,000, most of it in business assets, including some $150,000 in overdue “farmers’ paper”), generous but not extravagant provision was made for the family. In the Chautauqua spirit of educational pursuit, major gifts were again made to Methodist colleges (Victoria College, Mount Allison College, and the newly founded American University in Washington). The residue, well in excess of $1 million, was to be distributed by his executors in accordance with that spirit. The lengthy and difficult task was carried out by the reclusive Chester, his sister Lillian, and, later, Chester’s son Vincent; it continues in the Massey Foundation.

AO, Clarke Township, abstract index to deeds and deeds for concession 1, lot 28 (mfm.); Haldimand Township, abstract index to deeds and deeds for concession 2, lots 30–32 (mfm.); RG 22, ser.155, estate of Daniel Massey. Arch. of Massey Hall/Roy Thomson Hall (Toronto), Board of Trustees of Massey Music Hall, minute-book, 1894–1933. Baker Library, R. G. Dun & Co. credit ledger, Canada, 14: 60, 141. Can., Dept. of Consumer and Corporate Affairs, Patent Office (Hull, Que.), 52 patents issued to C. A. Massey, Massey Manufacturing Co., and Massey-Harris, 1878–96. CTA, RG 1, A, 1878–80; B, 1878–80. NA, MG 26, F: 5325–26; MG 28, I54 (mfm.); MG 32, Al; RG 31, C1, 1861, 1871 [industrial census, for implement producers identified in the text]. Ont., Ministry of Consumer and Commercial Relations, Companies Branch, Corporate Search Office (Toronto), Corporation files, C-2821. Ontario Agricultural Museum (Milton), Massey-Ferguson Arch. QUA, 2056, box 42. Toronto Land Registry Office, Ordnance Reserve titles, vol.110–12: 186–87, 190. UCC-C, Toronto City and Fred Victor Mission Soc. records; Methodist Social Union of Toronto; Victoria College Arch., Upper Canada Academy and Victoria College voucher-book, 1839–48: 33.

Can., House of Commons, Journals, 1888, app.3. Canadian Labor Reformer (Toronto), 25 Sept. 1886. Canadian Statesman (Bowmanville, Ont.), 1879. Monetary Times, 8 May, 9 Oct., 13 Nov. 1891. Cleveland city directory . . . (Cleveland, Ohio), 1871–83. Commemorative biog. record, county York. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.1. The Massey family, 1591–1961, comp. M. [L.] Massey Nicholson (Saskatoon, 1961). Toronto directory, 1880–96. C. [T.] Bissell, The young Vincent Massey (Toronto, 1981). Paul Collins, Hart Massey (Toronto, 1977). Merrill Denison, Harvest triumphant: the story of Massey-Harris, a footnote to Canadian history (Toronto, 1948). J. F. Findlay, Dwight L. Moody, American evangelist, 1837–1899 (Chicago and London, [1969]). Mollie Gillen, The Masseys: founding family (Toronto, 1965). G. S. Kealey, Toronto workers respond to industrial capitalism, 1867–1892 (Toronto, 1980). Theodore Morrison, Chautauqua: a center for education, religion, and the arts in America (Chicago and London, 1974). E. P. Neufeld, A global corporation; a history of the international development of Massey-Ferguson Limited (Toronto, 1969). W. G. Phillips, The agricultural implement industry in Canada; a study of competition (Toronto, 1956). N. A. E. Semple, “The impact of urbanization on the Methodist Church in central Canada, 1854–84” (phd thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1979). A. E. Skeoch, “Technology and change in 19th century Ontario agriculture” (undergraduate essay, Univ. of Toronto, 1976; copy in Royal Ontario Museum, Sigmund Samuel Canadiana Building, Toronto). Waite, Man from Halifax. Gordon Winder, “Continental implement wars: the Canadian agricultural implement industry during the transition to corporate capitalism, 1860–1940” (progress report for phd thesis research, Univ. of Toronto, 1987; copy in Ontario Agricultural Museum).

W. H. Becker, “American manufacturers and foreign markets, 1870–1900: business historians and the ‘New Economic Determinists,’” Business Hist. Rev. (Boston), 47 (1973): 466–81. Ramsay Cook, “Tillers and toilers: the rise and fall of populism in Canada in the 1890s,” CHA Hist. papers, 1984: 1–20. Gerald Friesen, “Imports and exports in the Manitoba economy, 1870–1890,” Manitoba Hist. (Winnipeg), no.16 (autumn 1988): 31–41. A. E. Skeoch, “Developments in plowing technology in nineteenth-century Canada,” Canadian Papers in Rural Hist. (Gananoque, Ont.), 3 (1982): 156–77.

Cite This Article

David Roberts, “MASSEY, HART ALMERRIN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/massey_hart_almerrin_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/massey_hart_almerrin_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | David Roberts |

| Title of Article: | MASSEY, HART ALMERRIN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | March 28, 2025 |