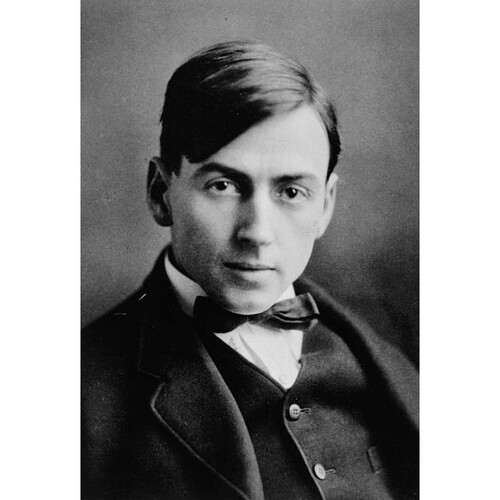

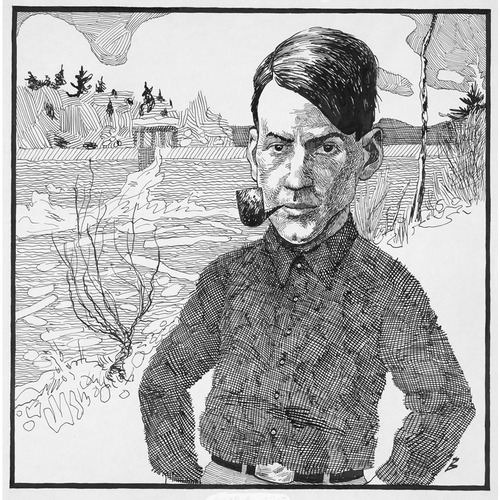

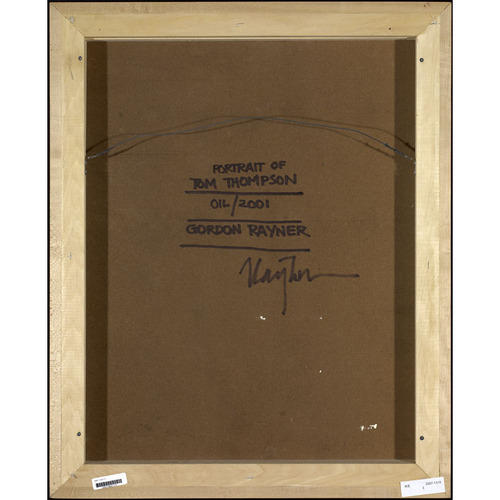

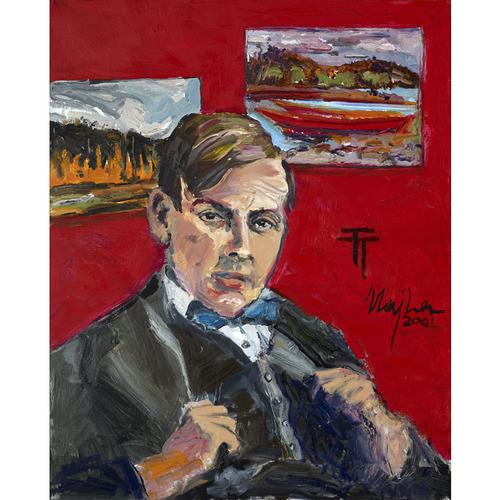

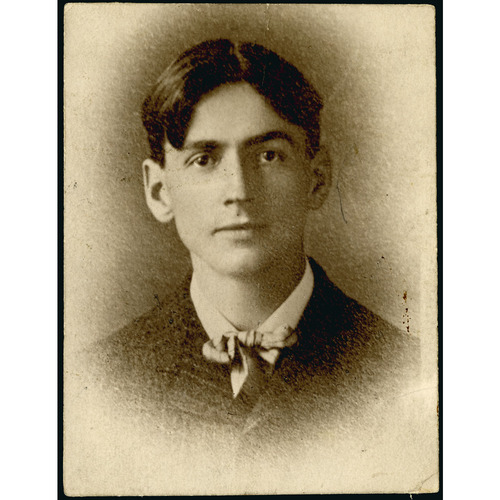

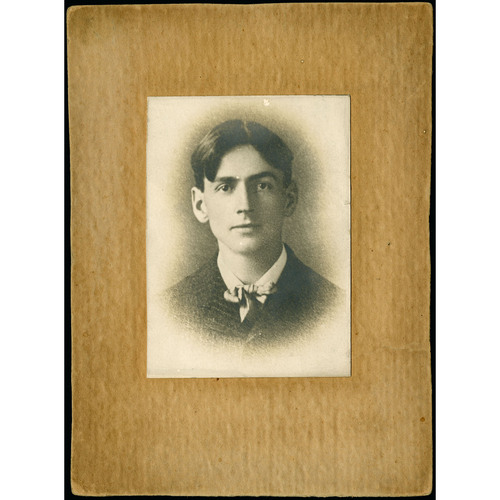

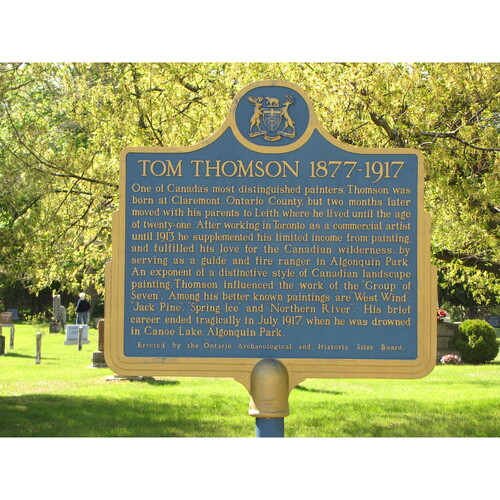

THOMSON, THOMAS JOHN (Tom), artist; b. 5 Aug. 1877 near Claremont, Ont., sixth of the ten children of John Thomson, a farmer, and Margaret Mathewson; d. unmarried 8 July 1917 in Algonquin Park, Ont.

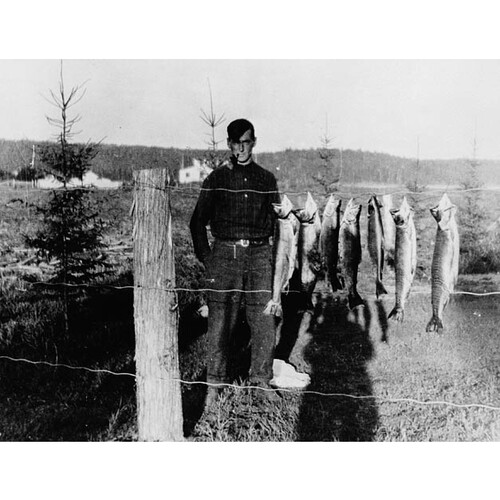

When Tom Thomson was just two months old, his family moved to a farm in the vicinity of Leith, near Owen Sound on Georgian Bay. Here he spent a normal boyhood; he particularly enjoyed tramping the woods, hunting, and fishing. He participated with his family in traditional cultural pursuits, singing in Leith’s Presbyterian church choir, playing the mandolin and perhaps other instruments, reading (especially poetry), sketching, and painting. At some point he left school for a year because of what was described as “weak lungs” or “inflammatory rheumatism” and roamed the countryside. It is not known if he finished high school.

When Thomson reached his majority, in 1898, he inherited approximately $2,000 from his grandfather, money he seems to have frittered away. The next few years were filled with uncertainty. He tried to enlist three times for service in the South African War, but was rejected each time because of fallen arches, according to his sister. In 1899 he was apprenticed as a machinist to William Kennedy and Sons in Owen Sound, but he stayed only eight months. After an interval at home, he followed the example of two elder brothers and enrolled in the Canadian Business College in Chatham, Ont. In 1901 he joined his brother George in Seattle, Wash., where George had helped establish the Acme Business College. Tom signed up there for a course in penmanship. After six months, he went to work for a photo-engraving firm. Perhaps predictably, the peripatetic Thomson soon accepted a higher-paying position with the Seattle Engraving Company. In all he spent three years in Seattle, during which time he seems to have initiated his study of commercial art and pursued, in desultory fashion, pen-drawings and water-colours. One of his earliest known works, Self-portrait: after a day in Tacoma, is from this period.

According to contemporaries, Thomson left Seattle precipitately in 1904 after he had been rebuffed in a marriage proposal. He went back to Ontario to continue the commercial-design work he found to his liking. For the next five years he worked for a variety of photo-engraving companies, including Legg Brothers of Toronto, possibly Reid Press of Hamilton, and, as of 1907 or 1908, Grip Limited in Toronto. As well, he began to use oil-paints in a tentative way. It is said that he took a few art lessons at this time, possibly from William Cruikshank, who taught life classes and traditional study of the old masters.

It was at Grip that Thomson found further stimulation for his artistic and philosophic interests. Albert Henry Robson*, the director of the engraving department, conducted what he called “a sort of graphic arts university.” Conscientious and astute, Robson hired artists of promise, among them James Edward Hervey MacDonald*, Franklin Carmichael*, Frederick Horsman Varley*, Arthur Lismer*, Francis Hans (Frank) Johnston*, Thomas Wesley McLean, William Smithson Broadhead, Harry Ben Jackson, and Thomson. The artists, formally dressed, sat at workbenches pushed close to the windows for light. Amid much fun and good spirits, work of high quality was produced. When Robson left Grip in October 1912 to join the art department of the printing firm of Rous and Mann Limited, Thomson and several others would follow him.

Robson’s influence was felt even outside working hours. Continuing an established artistic pattern, he took an interest in landscape painting and encouraged his staff to do likewise. Groups of painters, abandoning soup-can labels, petticoat advertisements, and the like, spent their Saturday afternoons and Sundays in the country around Toronto, outings similar to those conducted by the Toronto Art League and the Mahlstick Club. With Johnston, Thomson went on sketching expeditions to the Humber valley, and with others to Weston, Lambton Mills, York Mills, Lake Scugog, and beyond. Paintings done by Thomson during his years with Robson, such as Drowned land and Near Owen Sound, start to show promise in their dashing brushwork and apposite tones.

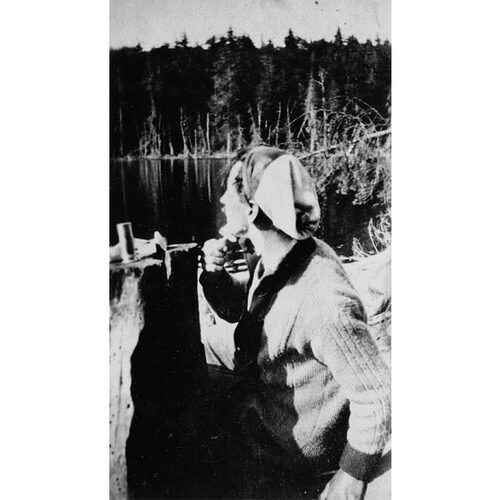

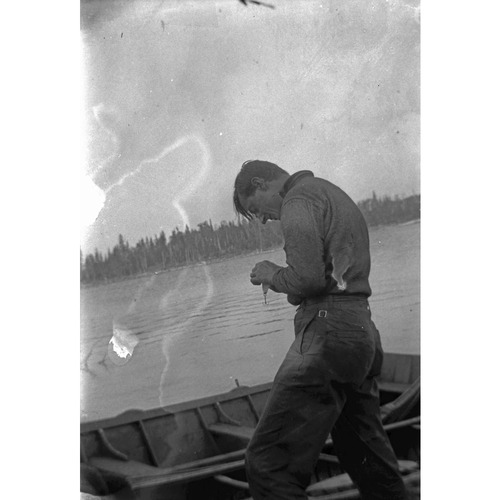

In May 1912 Thomson spent two weeks in Algonquin Park with H. B. Jackson. Already known by artists such as John William Beatty* and Tom McLean, the park was famous for its fishing and forests, and, most important, it was reachable by train. During August and September Thomson and W. S. Broadhead went on a long canoe trip much farther north, in the Mississaga Forest Reserve in the Algoma District. This trip seems to have been Thomson’s first extended experience in the wilderness. He appeared to be more interested in photography than in sketching, but back in Toronto he was encouraged to paint up one of his sketches. The result, A northern lake, is his first important canvas. Restrained in colour, the work gets its power from its open horizontal format – parallel stripes of rock, lake, distant shore, and sky, all framed by bare trees. This frontal perspective was to be used by Thomson over and over again with great success. In the Ontario Society of Artists exhibition of early 1913, A northern lake won the Ontario government’s purchase prize of $250.

Other contributions to this ground-breaking show also seemed to be forerunners of a new mood in Ontario, an intense interest in the Canadian wilderness of a sort not seen since Lucius Richard O’Brien* and others had painted the west. J. E. H. MacDonald exhibited six studies of Georgian Bay and Arthur Lismer hung The clearing, another work executed in the cottage country there. Two other exhibitors, Lawren Stewart Harris* and Alexander Young Jackson*, did not show Canadian landscapes, but among these four painters, as well as others, there was developing a conviction of the need to find a native expression in painting. Artistic developments in other parts of the country, such as the work of Maurice Galbraith Cullen* and Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté* in Quebec, did not, however, mirror this new Ontario thrust towards the theme of a peopleless wilderness with distinct seasonal features.

Through his friends at work, through exhibitions, and through the Arts and Letters Club, Thomson gradually carne to the attention of those men who, in 1920, would form the Group of Seven, Canada’s first national school of art. Stimulated by contemporary nationalistic feelings, which embraced the northern theme recurrent in English Canadian literature, and by the northern Symbolist landscapes hung in an exhibition of Scandinavian art in Buffalo, N.Y., in 1913, these men came to champion the wilderness as the strength of Canada, the north as the location of that strength, and populist, design-based techniques as preferable to “foreign-begot” methods. The fact that they were all southern urban dwellers who had learned art techniques abroad did not worry them one whit.

In May 1913 Thomson gave up his commercial design job and left to spend a season in Algonquin Park, sketching, guiding fishing parties, and perhaps fire-ranging. When he returned to Toronto in November, he brought with him at least 30 landscape sketches, including Lake, shore and sky, which he gave to A. Y. Jackson. James Metcalfe MacCallum, a prominent ophthalmologist, quietly became Thomson’s patron and promoter, and a supporter of the wilderness theme. Orchestrated by MacCallum, by January 1914 Thomson and Jackson were sharing a studio in the Studio Building, which MacCallum and Harris had just constructed in the Rosedale ravine. This association was to be mutually beneficial: from Jackson, Thomson learned about colour, for his formal training had been as a graphic artist; from Thomson, Jackson learned about the wonders of the north, for Jackson had till then concentrated on semi-urban and European locations. The association was strengthened by an article in the Toronto Daily Star of 12 Dec. 1913 written by Henry Franklin Gadsby, who derisively labelled the young artists the “Hot Mush School.” J. E. H. MacDonald’s reply, published a few days later, was devastating. Thus was started the tradition of goading the press to excess, a tradition that was to bring the Group of Seven frequent attention from both the press and the public.

In 1914 the painters focused on Algonquin Park, earning themselves another sobriquet, the Algonquin Park School. Tutored by Thomson, Jackson first visited the park in February. In May, Thomson introduced it to Lismer, who, in turn, worked with the inexperienced painter, bringing out, according to Jackson, Thomson’s skills as a designer and his potential for the use of colour. From the park Thomson moved on to spend some time with MacCallum at his cottage on Go Home Bay, on the southeastern shore of Georgian Bay. Sketching was intermingled with fishing and canoeing. In the fall he returned to the park, where he was joined by Jackson for six weeks and later by Varley and Lismer. Over the course of the year his friends discovered much about the quiet Thomson. He “came to life in the bush,” Lismer found, and in October Jackson wrote to MacDonald that in painting “Tom is doing some exciting stuff.”

During the winter of 1914–15 Thomson shared space in the Studio Building with Frank Carmichael. Here he painted up sketches he had produced over the summer. One of the resulting canvases was Northern river, a large piece that Thomson showed at the annual show of the OSA in March–April 1915 at the Toronto Public Reference Library. Northern river attracted attention right away. Commenting on the show, the Toronto Daily Mail and Empire called the work “one of the most striking pictures of its kind in the gallery.” Even Hector Willoughby Charlesworth*, the Saturday Night critic the Algonquin painters loved to goad, wrote of it as “fine, vigorous and colourful. The clever treatment of trees in the foreground gives a most effective composition.” In the foreground Thomson had placed a dark scrim of spruce trees, heavily massed on the right, with a single tree on the left joined by a partially fallen, curving trunk. Through this curtain shimmers the river and the brightly coloured bank beyond. Compositionally the work reflects the Art Nouveau technique of a curviform, organic foreground, dark in value and set off by a lighter middle and background. Well known, this technique was used in design work and by European painters, and was reproduced in international art magazines. Soon after the OSA show, the National Gallery of Canada acquired the “swamp picture,” as Thomson called it, for $500.

In 1915 Thomson returned to Algonquin Park, staying at Mowat Lodge on Canoe Lake. On 22 April he reported to MacCallum that the snow was virtually gone from the woods, but that the ice was still on the lakes, though it was rotting. From his favourite campsite, at the back of Hayhurst Point, he sketched Spring ice in his regular format, on an 8 ½ by 10 ½ inch birchwood panel. Although he had done some guiding the year before, he was not able to do as much this year. Visitors to the park were not as numerous because of World War I. Yet he was out with a group as early as 28 April. He painted sporadically, as was his style. In September he wrote laconically to MacCallum that he had not done much painting, only “about a hundred so far.” He travelled extensively. To MacCallum he wrote, “I will get on the trail again this morning[,] will go back up South River and cross into [North] Tea Lake and down as far as Cuchon [Cauchon Lake] and may make it out to Mattawa but its fine country up this river . . . so there is lots to do without travelling very far.” Thomson was lonely and hoped that Lismer or any of the other artists might join him. Jackson for one could not – he had enlisted in June. In the fall Thomson went to MacCallum’s cottage on Go Home Bay, where, with MacDonald and possibly Lismer, they took measurements and discussed plans for a series of decorative panels for it.

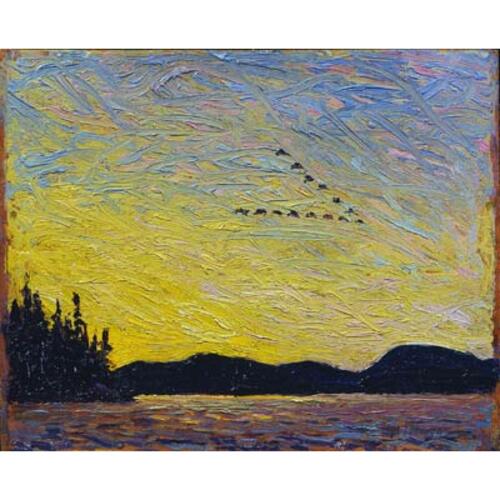

The sketches that Thomson produced in 1915 were more accomplished than his previous work, especially in the development of colour, where he used hues closest to the primaries. In Tea Lake dam he created a bold diagonal foreground of green foliage, a contrast to the inky lake, which he enlivened with fast-moving waters rendered by vigorous slashes of white, yellow, green, and orange. This activity is anchored by the dark horizontal dam, the far shore, and large clouds on the horizon. Blue Lake is similar in composition, though here Thomson added a curtain of birch trunks in the foreground. In Sunset he eliminated the foreground and concentrated instead on the sweep and grandeur of a red and yellow sky above dark hills and a reflecting lake.

In November 1915, before returning to Toronto, Thomson went to Owen Sound to see his sister Minnie Harkness and her family. On this occasion he talked about trying to enlist, but feared he would be turned down. Although he hated the war and Jackson’s involvement “in the machine,” as he called it, he was determined to try to participate. Just why he was refused is hard to know. Members of his family again suggested problems with his feet – a toe broken in his youth and faulty arches.

Since all the studios in the Studio Building had been rented for the winter, Harris and MacCallum renovated a small frame structure that had been used as a tool-shed during the construction of the Studio Building. Thomson moved in and built himself a bunk, shelves, a table, and an easel. Soon the shack, as it was called, attracted a stream of visitors. Ensconced there, Thomson tackled part of the commission from MacCallum for the panels for his cottage, which were to be a birthday surprise for his wife. MacDonald and Lismer were the other contributors to this fun-filled project. It appears that Thomson was to do seven panels, although only three were installed, in April 1916. Titled Forest undergrowth I, II, and III, they were executed in a flat Art Nouveau style with a limited palette, an approach closer to commercial-design work than to painting.

In the shack Thomson also worked on his larger canvases. Spring ice is based on the compositional format of both A northern lake and Jackson’s Frozen lake, early spring (1914), with the same high horizon and emphasis on a foreground framed by spindly trees. A comparison between the sketch and the finished canvas shows how he was willing to make subtle but important modifications to enhance mood. The hues of the sketch were an overall rosy brown. In the canvas he emphasized the difference between lake and land by setting off the cold blue lake against the orange-yellow land. As well, he added a pair of trees on the right edge to contain the piece. The pool and In the northland are compositionally similar and relate to Northern river with its emphasis on a decorative screen in the foreground. Yet in moving from sketch to canvas on these works, Thomson modified his palette and his vision by dropping the stylistic device of a dark scrim and using more primaries and fewer mixed hues in the foreground.

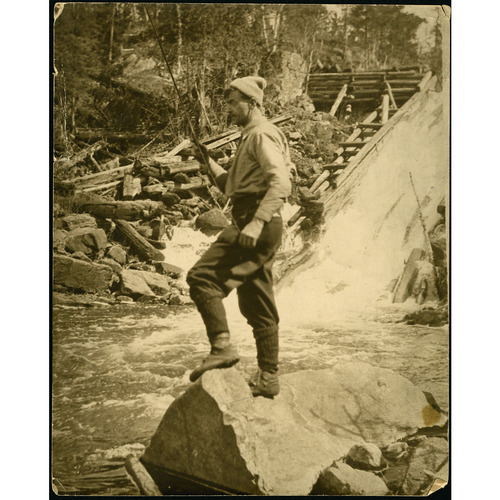

As soon as he could in the spring of 1916, Thomson returned to Algonquin Park. By now the call of the north was too insistent to be ignored. He started the season with MacCallum and possibly Harris and his cousin as companions, in the northeastern portion of the park. Petawawa gorges was one of the sketches that Thomson produced there. Others might well include his sketches for The west wind and The jack pine. To help support himself he took a season’s job as a fire-ranger; in May he reported for work in the park’s eastern section at Achray, a railway station at Grand Lake on the Petawawa River. Fire-rangers were assigned to specific areas and worked in pairs. Thomson and Edward Godin followed one of the timber drives of J. R. Booth and Company down the Petawawa below Grand Lake. According to a letter Thomson wrote to MacDonald, he found the location “a great place for sketching” and intimated he had had time to paint because there had been no fires. On 4 October, however, he reported that he had “done very little sketching this summer as I find that the two jobs don’t fit in.” He invited MacCallum to join him in Achray, noting that the fall colours would be at their best by the end of the week.

Despite Thomson’s disclaimer, he does not seem to have reduced his output greatly, especially in the spring and fall. Works such as Northern lights and Moose at night show his sure hand, his delight in the paint medium, his freedom of form, and his directness of approach. A boldness of colour contributes to the simplicity and immediacy of impact. Values and hues are laid down with vigorous and distinct brush strokes. Emphasizing the northern nature of the seasons, Thomson delighted in autumn foliage in pieces such as Tamaracks and The waterfall.

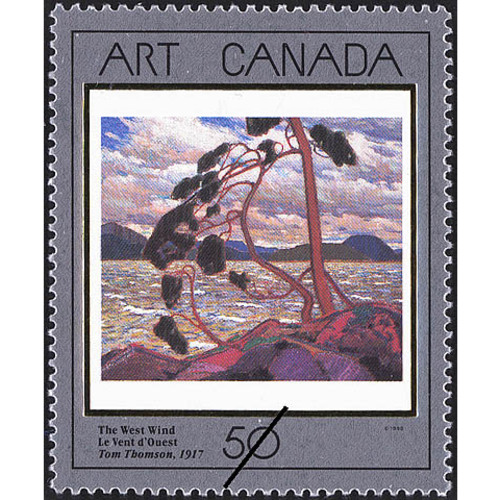

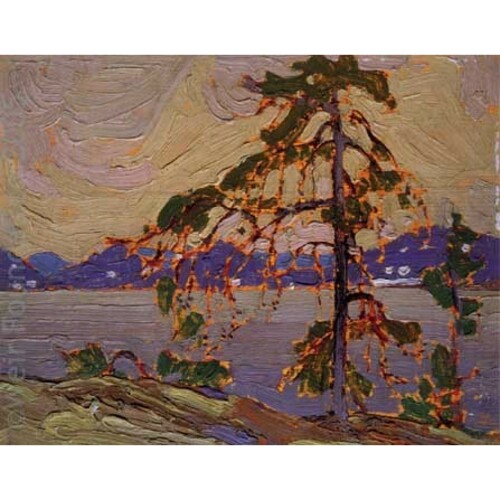

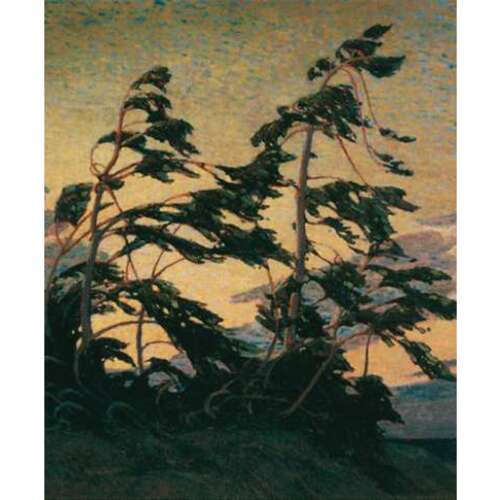

As had become his custom, Thomson returned that winter to his shack in Toronto to paint up his sketches. He worked on at least four canvases, including Woodland waterfall and The drive. The two that are best known today, icons of Canada, are The west wind and The jack pine. The west wind, which Lismer later described as “the spirit of Canada made manifest in a picture,” and The jack pine form an interesting contrast in mood but they are fundamentally alike in form. Each consists of a strong vertical (a single tree) overlaid on a series of horizontals (foreground, lake, distant shore, and sky). Writing about Thomson sketching furiously in the midst of a gale, Lawren Harris would later comment: “Here was symbolized . . . the function of the artist in life: he must accept in deep singleness of purpose the manifestations of life in man and in great nature and transform these into controlled and ordered and vital expressions of meaning.” Thomson himself rarely, if ever, discussed his artistic consciousness or techniques, a tendency that forces a discriminating analysis of his work and a cautious acceptance of posthumous judgements such as Harris’s. That Thomson was approaching the peak of his artistic power there can be no doubt. The west wind and The jack pine both speak to the artist’s deep interest in the mood of nature at a particular time in a defined place. The west wind is transitory, lithe, enduring; The jack pine is monumental, static, ageless.

Thomson returned to Algonquin Park in late March 1917, staying at Mowat Lodge on Canoe Lake. On 16 April he detailed to his brother-in-law Thomas J. Harkness his plans for the summer: “I will be camping again for the rest of the summer. I have not applied for the fire-rangers job this year as it interferes with sketching to the point of stopping it altogether so in my case it does not pay. . . . I may possibly go out on the Canadian Northern this summer to paint the Rocky’s but have not made all the arrangements yet.” On 28 April he took out his guide’s licence and in early July he noted that he had done some guiding and expected other trips with fishing parties later in the month and next, “with probably sketching in between.”

On Sunday, 8 July, Thomson set off in his canoe filled with fishing equipment and supplies. The canoe was seen floating upside down that afternoon. On 16 July his body was pulled from Canoe Lake. The verdict at the inquest was “death by accidental drowning.” The hurried nature of the inquest, however, left many questions unanswered. Those who knew Thomson found it difficult to accept such a verdict in the death of so skilled a woodsman. Rumours and speculation have continued, adding to the legend that Tom Thomson has become. His body was buried at Canoe Lake but was soon reinterred in Leith. A memorial cairn was placed by MacCallum near Hayhurst Point overlooking Canoe Lake in September. J. W. Beatty was responsible for the stonework and J. E. H. MacDonald designed the bronze plate.

Thomson’s fellow artists were among the first to mourn his loss and explain his contribution, at times with an exaggeration bordering on deification. From overseas A. Y. Jackson wrote to J. E. H. MacDonald in August: “Without Tom the north country seems a desolation of bush and rock. he was the guide, the interpreter, and we the guests partaking of his hospitality so generously given . . . my debt to him is almost that of a new world, the north country, and a truer artist’s vision because as an artist he was rarely gifted.” Later that month Jackson prophetically declared that Thomson “has blazed a trail where others may follow and we will never go back to the old days again.” With Thomson’s death the Algonquin painters conclusively ended their search for a subject. He had led them into Algonquin Park and, perhaps unwittingly, into a serious cult of nature. As well, with the help of his friends, Thomson had set a revolutionary style of wilderness painting. Lismer acknowledged that “even the Northland itself began to look like Thomson’s paintings.” Both the man and his art became a source of nationalistic inspiration for the painters who would form the Group of Seven. In 1927 Jackson called his friend “our ideal of an artist. The more you think of Tom Tompson the greater the man becomes.” Lismer wrote that “what he saw and did set the stage for what we know about Canada, satisfying the curiosity about the remote and vast hinterland of the North. If art . . . is a part of the national establishment then Thomson’s contribution was unique and stimulating.” For MacCallum, who did much to shape public perceptions of Thomson, the power of his works was their truthfulness to the north country, that special place which the Group of Seven would develop into the symbol of Canada. In 1918 MacCallum noted of Thomson: “The north country gradually enthralled him, body and soul. He began to paint that he might express the emotions the country inspired in him; all the moods and passions, all the sombreness and all the glory of colour, were so felt that they demanded from him pictorial expression.”

In 1918 the National Gallery of Canada bought The jack pine, Autumn’s garland, and 27 sketches. A memorial exhibition of his paintings was held at the Art Gallery of Toronto in February 1920. Although the reviewer for the Daily Mail and Empire felt that most viewers would be “shocked and startled and amazed,” he concluded that many of Thomson’s paintings “are colour raptures and that the great, free spirit of the northland blows unrestrained through his glowing and emancipated canvases.” The reviewer for the Rebel, Barker Fairley*, picked up on what he felt was Thomson’s weakness: his naïvety, his lack of artistic sophistication, the simplicity of his image making. Yet Fairley identified his work “as something stern, solid, horizontal, even static, that would itself be forbidding were it not wonderfully saturated with colour.” Lismer, Harris, and Jackson all saw Thomson’s relationship to the wilderness as his most important legacy. Lismer wrote that “Thomson was a sort of Whitman: a more rugged Thoreau if you will, but he did the same things, sought the wilderness, never seeking to tame it but only to draw from it its magic of tangle and season, its changing skyline and its quiet or vigorous moods.” The jack pine was part of Canada’s contribution to the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley (London) in 1924. Critics were overwhelmed by the Canadian paintings and the London Times described Thomson’s canvas as the most striking work in the show. The adulation has not abated. For his championship of the Canadian wilderness, for his delight in colour, for his uncomplicated rendition of a northern landscape, Tom Thomson has become one of Canada’s heroes, a considerable feat for an artist.

There are numerous monographs, studies, exhibition catalogues, and articles on Thomson’s life, work, and death. Only the most important items are cited here. Other sources published before 1971 are listed in A bibliography of the Group of Seven, comp. D. [R.] Reid (Ottawa, 1971); materials published up to 1981 are covered in Art and architecture in Canada: a bibliography and guide to the literature to 1981, comp. L. R. Lerner and M. F. Williamson (2v., Toronto, 1991).

Most of the extant Thomson correspondence is held in his file in the National Gallery of Canada Library, Ottawa. Additional correspondence is preserved at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ont. Material relating to him is also available in collections at the AO, including the William Colgate papers, sect.ii (F 1066, MU 583); documents concerning his death (F 775, MU 2130, 1917, no.4); and his birth registration (RG 80-2-0-99, no.20170). Public institutions holding his paintings include the Art Gallery of Ontario (Toronto), the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, the National Gallery of Canada, and the Tom Thomson Memorial Art Gallery, Owen Sound, Ont.

Published correspondence by Thomson appears in “Tom Thomson writes to his artist friends,” ed. W. [G.] Colgate, Saturday Night, 9 Nov. 1946: 20, and Two letters of Tom Thomson, 1915 & 1916, ed. W. [G.] Colgate (Weston, Ont., 1946).

Books concerning Thomson include Ottelyn Addison with Elizabeth Harwood, Tom Thomson; the Algonquin years (Toronto, 1969); Blodwen Davies, Paddle and palette: the story of Tom Thomson (Toronto, 1930) and Tom Thomson; the story of a man who looked for beauty and for truth in the wilderness ([rev. ed.], Vancouver, 1967); R. H. Hubbard, Tom Thomson (Toronto, 1962); W. T. Little, The Tom Thomson mystery (Toronto, 1970); Joan Murray, The art of Tom Thomson (exhibition catalogue, Art Gallery of Ontario, 1971); D. [R.] Reid, Tom Thomson: “The jack pine” (Ottawa, 1975) and Photographs by Tom Thomson (Ottawa, 1970); A. H. Robson, Tom Thomson (Toronto, 1937); and Harold Town and D. P. Silcox, Tom Thomson: the silence and the storm (Toronto, 1977).

Among the numerous publications dealing with the Group of Seven, the following are worth noting: F. B. Housser, A Canadian art movement: the story of the Group of Seven (Toronto, 1926; repr. 1974); Peter Mellen, The Group of Seven (Toronto, 1970); and D. [R.] Reid, The MacCallum bequest of paintings by Tom Thomson and other Canadian painters . . . ([Ottawa, 1969]) and The Group of Seven (exhibition catalogue, National Gallery of Canada, [1970]).

Articles by contemporaries include A. Y. Jackson’s foreword to An exhibition of paintings by the late Tom Thomson (exhibition catalogue, Arts Club of Montreal, 1919); L. [S.] Harris, “The Group of Seven in Canadian history,” CHA, Report, 1948: 28–38; three essays by Arthur Lismer: “The west wind,” McMaster Monthly (Hamilton, Ont.), 43 (1933–34): 163–64, “Tom Thomson, 1877–1917: a tribute to a Canadian painter,” Canadian Art (Ottawa), 5 (1947–48): 59–62, and “Tom Thomson (1877–1917): Canadian painter,” Educational Record of the Prov. of Quebec (Quebec), [70] (1954): 170–75; R. P. Little, “Some recollections of Tom Thomson and Canoe Lake,” Culture (Quebec), 16 (1955): 200–8; J. M. MacCallum, “Tom Thomson: painter of the north,” Canadian Magazine, 50 (November 1917–April 1918): 375–85; J. E. H. MacDonald, “A landmark of Canadian art,” Rebel (Toronto), 2 (1917–18): 45–50; Graham McInnes, “Tom Thomson,” New World Illustrated (Toronto), 1 (1940): 27–28; and H. Mortimer-Lamb, “Studio-talk,” Studio (London), 77 (1919): 119–26.

Daily Mail and Empire, 13 March 1915, 21 Feb. 1920. Toronto Daily Star, 10 Sept. 1927. Carl Berger, The sense of power; studies in the ideas of Canadian imperialism, 1867–1914 (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1970). Jonathan Bordo, “Jack pine – wilderness sublime or the erasure of the aboriginal presence from the landscape,” JCS, 27 (1992–93), no.4: 98–128. Joan Murray, “The world of Tom Thomson,” JCS, 26 (1991–92), no.3: 5–51. Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell).

Cite This Article

Ann Davis, “THOMSON, THOMAS JOHN (Tom),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 12, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/thomson_thomas_john_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/thomson_thomas_john_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Ann Davis |

| Title of Article: | THOMSON, THOMAS JOHN (Tom) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | December 12, 2025 |