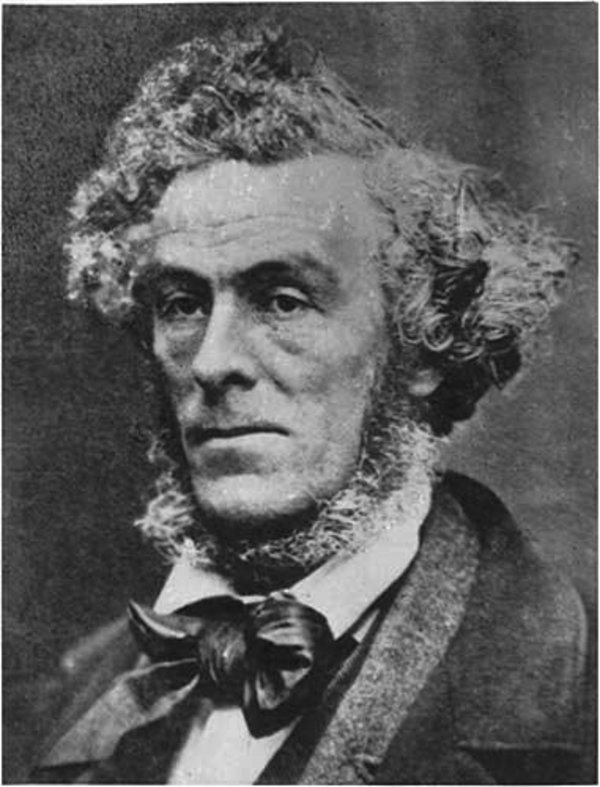

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

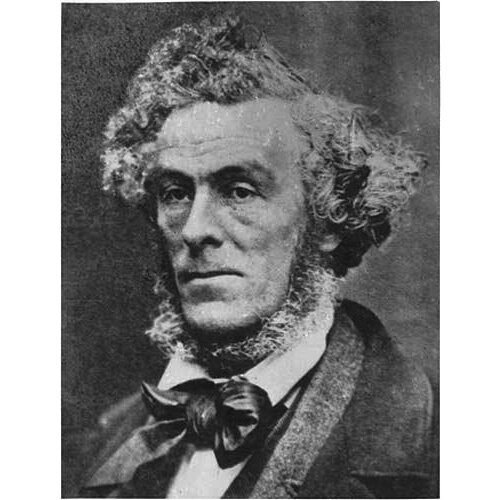

KRIEGHOFF (Kreighoff), CORNELIUS, painter; b. 1815 at Amsterdam, Holland, son of Johann Ernst Krieghoff, a coffee-house servant, who in 1811, at Amsterdam, had married Isabella Ludivica Wauters; d. 9 March 1872 at Chicago, Illinois.

Cornelius Krieghoff, the third of four children, learned the rudiments of music and painting from his father. At the age of 16 he was sent to relatives at Schweinfurt, Bavaria, to study painting. He returned to Düsseldorf two years later, where his parents had been living since about 1815–20; he no doubt studied here the works of artists who had been trained at its academy. Under the direction of their professor, Wilhelm von Schadow, these artists devoted themselves to genre painting, and presented similar subjects: card-players, drunkards, tricksters, outings, and children’s festivities. At the beginning of 1837 Krieghoff sailed for New York. There he enlisted as a volunteer in the American army, at a time of war against the Seminole Indians of Florida. On 5 May 1840, after three years in uniform as an artist, he was discharged at Burlington, Vermont. His services had earned him the rank of corporal. There is a record of his marriage, at Manhatten, to Louise Gauthier, dit Saint-Germain, a French Canadian. This is about all we know of Krieghoff before his arrival in Canada.

Anything else is a matter of hypothesis. His father, who apparently became a maker of carpets in Düsseldorf and also in Schweinfurt, was interested in arts and music. Young Cornelius is thought to have learned to play the violin, the guitar, the flute, and the piano. After his father’s death, he travelled with a friend, probably an artist like himself. Little is known about his travels. He may have spent two years at Rotterdam with his mother’s parents, and studied painting there. He was in Austria, Italy, and France, and then returned to Holland. His talents as a musician and painter do not seem to have been great enough to earn him a livelihood in Germany. He sailed for New York. For what reasons? To see his brother Ernst, who was settled at Toronto? To try his luck in America? Love of adventure? No doubt all of these. Unfortunately, the numerous pen and pencil drawings – about 100 – that he made while serving in the American army have been lost, and it is impossible to form an idea of this first artistic work. The circumstances attending his leaving the army and his marriage remain rather obscure. On the very day of his discharge, he rejoined the army, then deserted. The fact of his meeting Louise Gauthier perhaps explains his behaviour. Born at Longueuil, near Montreal, she had worked as a servant in New York. The reaction of her father, a fairly well-to-do farmer, to the announcement of the marriage is not known. Finally, there is no link which would make it possible to determine what influence American genre painting may have had on Krieghoff’s work.

The young couple decided to leave the United States and settle in Canada. They went to Toronto. The reasons for their choice, and the length of their stay, are unknown. Ernst Krieghoff no doubt advised his brother to take up residence in Toronto because of its artistic activities. He owned a studio of photography, and was probably acquainted with the possibilities open to a young artist. Cornelius worked as a professional painter, belonged to an art circle, and exhibited at the Toronto Society of Artists in 1847. But all had not gone according to his wishes, since by that date he had already left Toronto for Longueuil; two years later he went to Montreal to live. In five years there he occupied four different dwellings.

Montreal did not bring good fortune any more than had Toronto or New York. His pictures would not sell: he went from door to door and offered his paintings for $5 or $10 each. The merchants and important businessmen had scant interest in painting, and furthermore Krieghoff’s subjects held little attraction for them. They could not look too favourably upon scenes, costumes, and dwelling-places that reminded them of their peasant origins. He was expected rather to do paintings of horses imported from England, and signs for banks and stores. In fact Cornelius Krieghoff became more or less a housepainter in order to provide for his wife and their daughter Emily, who had been born in 1841.

The city of Quebec, however, possessed an aristocracy, formed of military men of a certain standing and other officers, who attached some importance to things of the mind. Moreover in the colleges and in society numerous literary, philosophical, and musical circles were being formed. At the Petit Séminaire of Quebec alone, more than seven societies came into being. People liked to meet to discuss literature, hear a play, and also on occasion talk about painting [see Octave Crémazie].But this discussion was hardly art criticism; the aesthetic concerns of European art centres were on a quite different level. The English officers liked to send their families a canvas on which was perpetuated some typical scene of the Canadian countryside or its people. The merchant wanted to have his own portrait, a tangible sign of his importance.

In 1851 Krieghoff had an opportunity to make contact with a representative of this society. John Budden, an auctioneer for A. J. Maxham and Company, met him at Montreal and bought some pictures from him. Did Budden make certain proposals to Krieghoff? Did he know him already or was this the first meeting? We do not know. But the pictures must certainly have captivated people in Quebec, for three years later Budden again met Krieghoff at Montreal and brought him to Quebec with his family. This new migration seems to have been carried out without much enthusiasm. Once more the family had to leave an environment to which they had become accustomed, and their relatives. Ernst had come to take up residence at Montreal with his wife and three children, and Cornelius would apparently have liked his brother to follow him to Quebec.

Cornelius Krieghoff resided at Quebec for 11 years: 11 years of intense productivity, 11 years of prosperity. Budden shared his house with the Krieghoff family, and introduced the painter to his friends and acquaintances. The artist met influential people, and was even host to the governor general, Lord Elgin [Bruce*]. Too much importance should not be attached to this visit, but undoubtedly such marks of esteem contributed greatly to the growth of Krieghoff’s popularity. With Budden, he took numerous trips around Quebec, to see people and landscapes and to familiarize himself with ways of living. Two schools asked him to give a few hours’ teaching: the Quebec School for Young Ladies and Miss Plimsoll’s establishment. His teaching seems to have been confined to having his pupils copy his own paintings.

During the year 1854 Krieghoff went to Europe for six or eight months. Little has been discovered about this voyage. We do not know if he went alone, his reasons for going, or the countries he visited. To a desire to see once more the places of his youth were probably added practical reasons, such as the opportunity to make a show of his popularity and to meet the English publishers who had made engravings of his works. He may have stayed two months in Paris, where he sold a collection of Canadian plants assembled during his excursions in the woods. Of his alleged stay in Germany nothing is known. This voyage does not seem to have had great importance from the strictly artistic point of view, for Krieghoff’s manner underwent no change during the succeeding years.

The same was apparently not true of his family life. His wife disappeared, but no one knows when or how. Some say that she left Krieghoff, discreetly, after they arrived at Quebec; others assert that she died at Longueuil in 1858 after a short illness. However, the Archives Judiciaires of Quebec and Longueuil possess no death certificate in the name of Louise Gauthier for the year 1858. Krieghoff may have had a second wife, about whom we are ignorant. His life is thus hardly known, and the most important sources of information about Krieghoff are indubitably his paintings.

Krieghoff’s art found its inspiration in everyday life and in the countryside surrounding Quebec. No mythological painting came from his studio. Was it through ignorance of the ancient literatures? It does not seem so, for he possessed a well-stocked library and had seen European paintings in museums. There are also no nudes; the one he painted, around 1844, was a cause of some scandal in his entourage. Religious themes are rare too: no Pietà, no Madonna with child, no Vision. He did paint a few religious pictures, but they are really studies of manners with religion a pretext for a subject.

Cornelius Krieghoff was a genre painter. He was interested not in what had happened once at a given spot, but in what was going on every day around him. His characters are not important individuals in themselves; rather they present an image of a particular profession or social group, or of people of a particular age. The humour that breaks through in the majority of his canvases gives to his work an air of gaiety which recalls the great age of genre painting, the Dutch 17th century.

Genre painting in the 19th century is part of a wider phenomenon that René Jullian has rightly called paysannerie. The peasant world did occupy some place in the minds of artists and writers before this period, but it was not a major preoccupation. Even when they became interested in the peasant, they surrounded exact details with an idealized setting, as in the novels of George Sand. In painting, Millet directed his art exclusively towards paysannerie, as we see in “La Barateuse,” “The Winnower,” and many others. In the same way Courbet wanted “living art” in his “Stonebreakers,” “Vendange à Ornans,” and “Paysans de Flagey revenant de la foire.” Novelists, such as Max Buchon and Balzac, described peasant customs at length, and showed various social groups in opposition. In Spain, Leonardo Alenza y Nieto, an admirable costumbrista, was untiring in his descriptions of the maja, the casuchas, the poor, and all the little people of Madrid. Krieghoff also made peasant life his principal theme. Without seeking to idealize, he depicted numerous scenes showing the customs and landscapes of a given region, and his regionalism thus linked him with this artistic movement of the 19th century. In the same way as Max Buchon and Courbet revealed Franche-Comté, and Alenza portrayed Madrid types, Krieghoff took the inhabitants of Quebec as his theme.

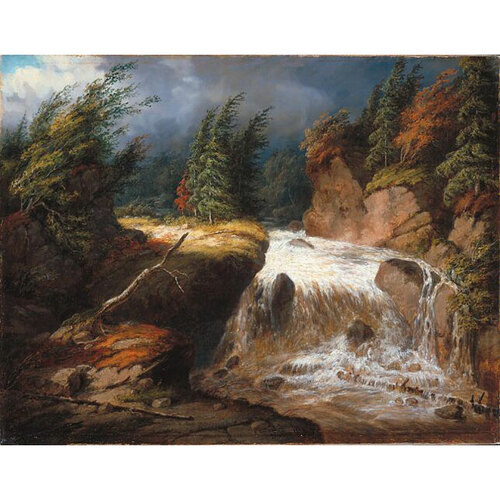

Krieghoff was interested in the imposing natural setting of the town of Quebec, and made it a favourite theme. The main subject of many of his pictures is the landscape. Landscape appeared tardily in Canadian painting with the first efforts of Joseph Légaré*. Krieghoff seems indeed to have been the first to take a constant interest in landscapes. Untiringly, he painted the rich colours of autumn at the moment when the forests are decked with the brightest vermilions, dazzling yellows, and deep greens. Many have taken him to task for using over-bright colours, without being aware of the brilliance of the Quebec forests in the autumn, when, for example, a sheet of water doubles their image. The mother-of-pearl whiteness of winter appealed to his palette just as strongly, and he has given us a great variety of landscapes in which firs and birches share the vast expanses of snow. Mountains pleased him equally, and serve as a backdrop for many compositions whose principal theme is the Canadian farm. Generally his attention was taken by a squalid looking dwelling. He has been reproached for painting tumble-down houses rather than the lavish seigneurial mansions of the Beaupré shore, and admittedly he has not left many pictures representing the aristocracy, but it is useless to hold this against him. His farms are pleasing because of their calm and realistic character. The little house with the pointed roof, the shelter where firewood and tools are to be seen, the shed some distance away, the sleigh pulled by a workhorse, the children playing in the snow: here was the spectacle that the Quebec countryside set before him. Often a stream runs through his paintings, or a lake occupies the centre of the composition. The river motif returns frequently, and he has left images of the Montmorency as well as of the lakes close to Quebec.

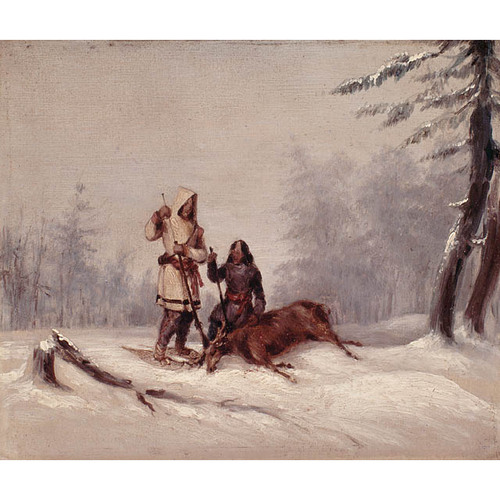

Krieghoff observed the work people did, and transposed its picturesque aspects to his canvas. He liked to represent the sugaring-off time, when the whole family shared in gathering the sap of the maple and the mother busied herself boiling the liquid under a shelter of planks. With tireless enthusiasm he repeated hunting scenes in the great forests. Wearing snowshoes and heavily clothed, the hunters pursue the stag and exhaust it in the soft snow before bringing it down. Sometimes it is their conquered victim that is the centre of the composition. He also portrayed trappers at work or workers busy laying in stocks of ice.

But Krieghoff’s most engaging theme is perhaps that of people enjoying themselves. The inn scenes show gatherings of jolly fellows who are having a fling, dancing and drinking copiously. The canvas called “Merrymaking” is undoubtedly his greatest success with this group. Other scenes at the Jolifou Inn similarly delight by their spontaneity. The men have gone to get the horses from the stable, and harness them either to a heavy sleigh or to an elegant carriage. Meanwhile, the women are taking their leave on the inn porch or giving their husbands the blankets that have been carefully warmed to protect them from the cold during the journey. Others are adjusting their snow-shoes. The “fiddler” has come out, violin and bottle in hand, and takes the first step of a dance, to the amusement of the people around.

It is well known that at this period the French Canadians valued their horses greatly: the animal’s beauty, and his skill and speed, were important to them. On many occasions Krieghoff depicted wild rides on the snow and ice, and the moment when two teams entered into competition. He often represents a low sleigh on which two or three men stand to travel over the countryside. At that time Montmorency Falls drew people of every class because of its varied attractions. The great frozen plain was eminently suitable for drives, and the women of fashion showed off their rich finery. The men guided their elaborate and high-spirited teams with an air of pride. The enormous ice cone at the foot of the falls delighted sliders, who found this place less formal than the slide before the citadel. Drinks were even served in a little room set up in the cone itself. The seminary of Quebec possesses an admirable print of Krieghoff’s representing this place, with dozens of small figures enjoying themselves in a fairylike setting. Even the games of children – who are numerous in Krieghoff’s work – captured his attention. They are most lively when they are coming out of school: they jostle each other, organize snowball fights, or slide on brightly coloured toboggans.

Travellers often appear in the artist’s pictures. A canoe glides silently over the water or passes between banks covered with vegetation. Even in the 19th century the canoe was still a principal means of locomotion. There were portages around rapids and dangerous spots; it might be necessary to risk paddling between blocks of ice, or to hoist the canoe onto a frozen surface and then put it back in the water: all this in icy temperatures. These were the conditions under which the mail was dispatched from Quebec to Lévis and travellers ventured the crossing. Each year the Quebec carnival revives these perilous scenes, which Krieghoff has immortalized. Other kinds of locomotion – horse and snow-shoe – offered material for interesting studies.

Paintings of the fur trade with the Indians and the transporting of pelts give an opportunity to observe men, rough and strong, who resemble the lumbermen of today. The pedlar, the timber merchant, the go-between, even customers of the general store appear in this world of tough, grasping individuals.

Religious scenes are infrequent in Krieghoff’s work. The mystical aspect of convent life, the activities of clergy or nuns, interested him little. When he did portray a member of the clergy, Krieghoff sought rather to express a tension between two social groups. One thinks of “Le Carême”: the parish priest calls on a family unexpectedly and finds that they are feasting away royally. This is a grave offence against religious precepts and against the priest, who expected every home to take his rigorous teaching seriously.

The Indians, also, are a rich source of inspiration for Krieghoff. No doubt he came into contact with them in the United States, during the expedition to Florida. At Montreal he painted the Indians of Caughnawaga, and at Quebec, those of Lorette. The majority of scenes are situated in the Laurentians, where the Indians are portrayed in habitual dress and their special way of life. He shows their sleighs, their mocassins, their great bright-coloured cloaks. Women place their children near a fire, in a basket made of branches or leather thongs, and prepare a meal, while the men smoke their long pipes. Or else we see Indians with baskets they have made for sale. This social group, still strongly individualized at the time, had in Krieghoff a sympathetic and prolific interpreter.

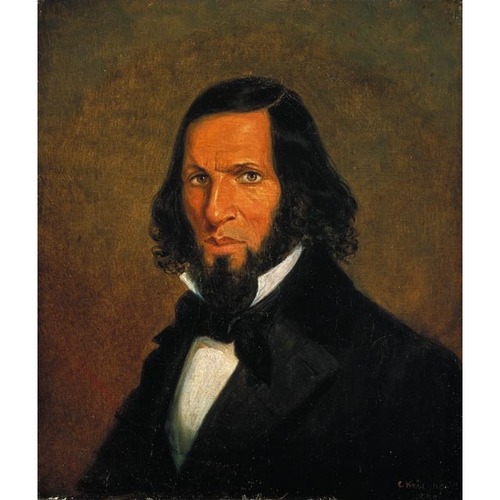

Krieghoff as a portrait-painter had a period of real celebrity. “He shows us the old Canadien, with keen, clear eye, slightly hooked nose, mat complexion, cheeks ruddy and brightened by the winter cold, and graying side-whiskers, which frame the face of a man wrapped and buttoned up to his neck in his cloak of local cloth.” As well as these portraits, in which he reproduced the features of those who lived around him, he did others of important people, for example, Lord Elgin. The McCord Museum at Montreal possesses a fine portrait of this governor. Krieghoff has also left us an interesting portrait of his friend John Budden. Elegantly garbed in check trousers and a golden-brown jacket, he is in a restful pose, nonchalantly seated by a stretch of water. Behind him he has placed his tall hat, his gun, and his game-bag. Krieghoff did not miss the opportunity to recall his subject’s partiality towards hunting. The scene stands out against a background of forest and heavy rocks.

Krieghoff painted an enormous number of pictures, and it is at present impossible to determine exactly the extent of his work. From the catalogue of 500 pictures established by Charles-Marius Barbeau*, a number must be removed. On the other hand, many should be added. He seems to have painted some 700 pictures. Nine were destroyed in the chamber of the Legislative Assembly when the parliament of Quebec was burned down in 1881, others have been stolen. A re-evaluation of Krieghoff’s art would necessitate a systematic effort to establish an exact catalogue of his works. While this task remains to be done, fresh information may come to light but Krieghoff’s work cannot be known in all its complexity.

Krieghoff does not seem to have done any engraving himself, but he may have had works lithographed during 1848, that is during his stay at Montreal. Lithography, a new technique, had been invented in 1796 and had become popular in Europe during the 1820s. In 1848 Krieghoff had four of his paintings lithographed by the firm of Borum in Munich. These lithographs, dedicated to Lord Elgin, were sold by subscription. Then a Philadelphia company published two prints representing beggars: “Pour l’amour du bon Dieu!” and “Va au Diable!” In 1860 John Weals of London published at least two engravings: “Passengers and mail crossing the river,” and “Indian chief.” The seminary of Quebec possesses an excellent coloured engraving representing “The Ice Cone at the Falls of Montmorency.” This print was made by the lithographic studios of Day and Son of London, and published by the Ackermann Company.

Was Krieghoff a prolific sketcher? It seems not, since no known drawing of his now exists. For some years it was thought that an admirable book of 36 sketches, representing several sites at Montreal, was his work, but it has now been proved that these are by James Duncan*. Krieghoff’s impulsive temperament was probably ill suited to lengthy study; he painted from life and without the help of preliminary sketches.

Krieghoff is perhaps one of the most controversial Canadian artists. Some praise him to the skies, others cannot find sufficiently uncomplimentary expressions to apply to his work. In the 19th century Krieghoff seems to have been much appreciated, and to have sold his paintings easily. At Quebec, the English officers, who liked to buy souvenirs for their families, were ready purchasers of his pictures, offered at trifling prices. This popularity can be confirmed from the auction sales organized by the firm of Maxham to which Budden belonged.

On 1 Aug. 1861, Le Journal de Quebec announced for 7 August a sale of engravings collected by Krieghoff. On 21 December the same paper announced a sale of 100 of his works, mentioning “Divertissement” [“Merrymaking?”] and “The Alchemist.” The lot included copies after English and other masters. It was stated that “this is the last and sole opportunity to procure works from the pencil of Mr. Kreighoff, since he is soon leaving for Europe.” But the sale seems not to have taken place, for almost the same announcement appeared on 27 March 1862. This time the lot sold fairly well, since on 13 December the firm announced the sale of the remainder of the lot, that is 30 paintings with Canadian subjects and a few engravings. On 13 December also, Le Journal de Quebec informed its readers of the sale of his collection of stuffed birds, of coins and Chinese curios, and particularly of his library, made up of 1,200 volumes, historical and scientific as well as classical. His library can therefore be considered among the large private libraries, the majority of which in the first half of the 19th century contained less than 500 volumes. This sale casts new light on the painter’s personality. His vast curiosity and his collector’s tastes prove indeed that Krieghoff was not the gay dog, the tippler and roisterer, that people have taken pleasure in presenting, by identifying him too readily with certain figures in his paintings.

After Krieghoff left Quebec, works still appeared on the market. Thus, on 18 Oct. 1870, Le Journal de Quebec announced a sale of paintings from Europe and “some Canadian, Russian, and English subjects by Krieghoff.” There was apparently no auction sale of Krieghoff’s works before 1862, but before he left the artist wanted to sell off his works, his collections, and even his furniture. It would therefore be an exaggeration to say that it was the auctioneers of the firm of Maxham who launched Krieghoff, by ordering pictures from him which would fetch a good price thanks to skilful publicity. The truth seems simpler. Krieghoff sold his pleasing, lively canvases regularly to art lovers. On the eve of his departure, his friend Budden helped to sell his collections and works by putting them up for auction.

The announcement of his leaving Quebec in 1862 raises a few problems. The artist does not appear to have gone to Europe. It seems more likely that he rejoined his daughter Emily and lived with her from then on. Her first husband had been Lieutenant Hamilton Burnett, whom she had married at Quebec; her second was Count de Wendt, a Russian who had emigrated to Chicago. At the end of his life, Krieghoff may have visited Quebec and Montreal. On 9 March 1872 he died suddenly at Chicago.

In the 20th century two currents of opinion have formed, while the commercial value of his works continues to soar. In 1893 John George Bourinot* first praised Krieghoff in his volume Our intellectual strength and weakness. He commended him as the first painter to draw attention to the beauty of Canadian scenes, and George Moore Fairchild corroborated this judgement in 1907. Henri-Arthur Scott exaggerated so grossly the value of this artist that it was easy to foresee an eventual reaction in the opposite direction. Scott, lost in admiration, exclaimed: “We have seen paintings of Krieghoff, sunsets of a brilliancy that truly recalls the marvellous splendours of the western sky, and permits us to affirm that the richness of his palette was in no way inferior to the finest examples of this genre in the museums of Europe. But why then is this painter not known over there, not placed among the great landscape-painters, the Corots, the Courbets, the Ziems, the Théodore Rousseaus ? He painted our ‘few acres of snow,’ and this was not enough to stir up public opinion in Europe.” In 1925 Newton McFaul MacTavish*, speaking of Krieghoff’s talent for caricaturing the types that he encountered, compared him to William Hogarth.

But from 1922 on another current of opinion was appearing, a current created and fed by French Canadians alone. Pierre-Georges Roy* stated that Krieghoff’s painting could not be valued highly as an artistic achievement. If his paintings sold well it was because he was a foreigner, and was the only one to have treated local subjects. These opinions have clashed and contradicted each other particularly since 1934, the year of the publication of Marius Barbeau’s romanticized study. Numerous criticisms of Krieghoff have appeared in reviews and journals; some have been openly hostile. Jean Chauvin reproached him with liking “the common people, carousing, noisy merrymaking, and knock-about farce,” and with putting his farmers “in huts that looked more like pigsties.” Two years later Maurice Hébert derided Krieghoff’s characters in violent language. “What Prussian faces they display, or should we say Bavarian or Dutch snouts! One of the men lifts a glass of spirits, rubs his belly, licks his chops, and slobbers, all in a grossly stupid manner.” Gérard Morisset* took up these judgements on his own account, and amplified them. According to him, “this painter is a gay dog who does not disdain to souse with his monied clientele; he turns out pictures, as a manufacturer would, which are within everybody’s grasp because of the carousing that he depicts, the besotted faces of his figures, the rather crude comedy of his genre scenes, and his autumn landscapes with their violent and loud colours.” It is true that his canvases please people. Since 1847 the majority of the exhibitions of traditional Canadian art have included pictures by Krieghoff. The 163 paintings exhibited in 1934 caused a stir of interest around Krieghoff, and the prices of his works have not ceased to rise. His paintings sell now for $8,000, $18,000, and even $45,000.

Misunderstandings have distorted many judgements passed on Krieghoff’s art. Certain critics, aristocratic in their taste, wanted grand subjects, noble and worthy themes. Krieghoff, they say, ought to have used a bold brush to paint a complete panorama of French Canadian life in the 19th century. If he had depicted the aristocracy, the rich manor-houses and the stately ceremonies of the period, he would have been pardoned an occasional incursion into less exalted fields. But to devote his entire art to peasants, and to the humble setting in which their undistinguished life unfolded, was unthinkable. He is blamed in addition for not being a truly Canadian artist, and for drawing his inspiration too narrowly from the 17th century Dutch. Are we so certain that Krieghoff always wanted to be a “Canadian” artist? Did not his clientele like to buy “Russian and English” subjects, as we can see from Le Journal de Québec of 18 Oct. 1870? Numerous canvases certainly recall the Dutch, but the attitudes of the characters and the details of the composition are indeed Krieghoff’s. Disappointed at not finding in him all the aspects they would like to see, certain people have come to the point of being unable to appreciate his art.

His themes have great interest in themselves and for their historical value. He is one of the first artists to draw his inspiration from the French Canadian milieu. He perpetuates customs and traditions which it would be hard to rediscover in another way. Krieghoff as a genre painter is undeniably pleasing, and his regionalism, far from lessening the value of his art, adds a component to the vast current of ideas centring around the peasant, both in Europe and in America. Certainly he is not a great master, but his technique is good, and his compositions are simple and firm. With deft touches he paints the face of an old man with graying hair, but he is just as adept at grouping several figures on a canvas, as his scenes of merry-making prove. Thus, brought back to more accurate proportions, Cornelius Krieghoff’s work occupies an important place in the evolution of the arts in Canada.

AJQ, Registre d’état civil, mariage d’Emily Krieghoff. Gazette (Montreal), 23 June 1951; 16 March, 28 Oct. 1957; 19 March, 29 Nov. 1958; 13, 23 April 1959; 4 June 1963. Le Journal de Quebec, 1er août 1861 (announcement of a sale of engravings by Krieghoff), 21 déc. 1861; 27 mars, 13 déc. 1862 (lists of paintings sold); 21 mai 1869 (list of paintings exhibited). Montreal Star, 22 May 1958, 12 March 1963, 19 Nov. 1966. La Presse (Montreal), 25 oct., 28 oct., 8 nov. 1957; 12 déc. 1958; 16 mars 1959. Le Soleil (Quebec), 10 déc. 1966.

Edwy Cooke, Cornelius Krieghoff, ca 1815–1872 (Fredericton, n.d.). The development of painting in Canada/Le développement de la peinture au Canada, 1665–1945 (Toronto, 1945). Encyclopedia Canadiana, VI, 21. Encyclopedia of Canada, III, 348-49. Exposition rétrospective de l’art au Canada/The arts in French Canada, Gérard Morisset, édit. (Quebec, 1952). R. H. Hubbard and J.-R. Ostiguy, Three hundred years of Canadian art: an exhibition arranged in celebration of the centenary of confederation/ Exposition organisée à l’occasion du centenaire de la confédération (Ottawa, 1967). Mexico, Museo nacional de arte moderno, Arte Canadiense ([Mexico City?, 1960]). Ottawa, National Gallery, Exhibition of Canadian painting to celebrate the coronation of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II (Ottawa, 1953). Le peintre et le Nouveau Monde; étude sur la peinture de 1564 à 1867 pour souligner le centenaire de la Confédération canadienne/[The painter and the New World]; a survey of painting from 1564 to 1867 marking the founding of Canadian confederation (Montreal, 1967). A. H. Robson, Catalogue of Toronto centennial historical exhibition, paintings by Cornelius Krieghoff . . . ([Toronto, 1934]). Toronto, Art Gallery, Painting and sculpture; illustrations of selected paintings and sculpture from the collection (Toronto, [1959]). Treasures from Quebec; an exhibition of paintings assembled from Quebec and its environs/Trésors de Quebec; exposition de peintures provenant de Quebec et des environs (n.p., [1965]). United States, National Gallery of Art, Canadian painting, an exhibition arranged by the National Gallery of Canada (Washington, 1950). Vancouver, Art Gallery, The arts in French Canada/Les arts au Canada français ([Vancouver], 1959). Wallace, Macmillan dictionary, 374–75.

[C.] M. Barbeau, Cornelius Krieghoff, pioneer painter of North America (Toronto, 1934). J. G. Bourinot, Our intellectual strength and weakness; a short historical and critical review of literature, art and education in Canada (Royal Society of Canada series, 1, Montreal, 1893). Canadian painters, from Paul Kane to the Group of Seven, ed. D. W. Buchanan (Oxford and London, 1945). Antonio Drolet, Les bibliothèques canadiennes, 1604–1960 (Ottawa, 1965). G. M. Fairchild, Gleanings from Quebec (Quebec, 1908), 66–74. J. R. Harper, Painting in Canada, a history (Toronto, 1966). R. H. Hubbard, The development of Canadian art (Ottawa, 1963). J.-S. Lesage, Notes et esquisses québecoises; carnet d’un amateur (Quebec, 1925), 52–57. N. M. MacTavish, The fine arts in Canada (Toronto, 1925), 15–20. Gérard Morisset, Coup d’œil sur les arts en Nouvelle-France (Quebec, 1941), 85–87. A. H. Robson, Cornelius Krieghoff (Canadian artists series, Toronto, 1937). P.-G. Roy, “Les peintures de Krieghoff,” in Les petites choses de notre histoire (7v., Lévis, Qué., 1919-44), IV, 168–71. H. A. Scott, Grands anniversaires; souvenirs historiques et pensées utiles (Quebec. 1919), 297–99.

[C.] M. Barbeau. “Krieghoff découvre le Canada,” RSCT, 3rd ser., XXVIII (1934), sect.i, 111–18 and 3 illustrations; “Kreighoff’s [sic] early Canadian scenes. Varied, resourceful, embracing,” Montreal Daily Star, 17 March 1934. Hébert Budden et al., “Cornelius Kreighoff [sic],” BRH, I (1895), 45–46. Jean Chauvin, “Cornelius Kreighoff [sic] agier populaire,” La Revue populaire (Montreal), juin 1934. William Colgate, “Krieghoff, pictorial historian,” Mail and Empire (Toronto), 8 Jan. 1935. E. A. Collard, “Krieghoff’s beautiful oil-paintings,” Gazette (Montreal), 14 March 1959. A. Ch. de Guttenberg, “Cornelius Krieghoff,” Revue de l’université d’Ottawa, XXIV (1954), 90–108. Maurice Hébert, “Quelques livres de chez nous: Cornélius Krieghoff,” Le Canada français (Quebec), XXIV (1936–37), 162–65. “The Jolifou Inn by Krieghoff,” Weekend Magazine (Montreal), V, no.52 (1955). Kay Kritzwiser, “Laing galleries.” Globe and Mail (Toronto), 12 Feb. 1966. Michel Lapalme, “Krieghoff à l’encan,” Le Magazine Maclean (Toronto), May 1969, 59–61. Gérard Morisset, “Cornelius Krieghoff. Réflexions en marge du livre de Marius Barbeau,” Le Canada (Montreal), 19 janv., 21 janv. 1935. “Six Krieghoffs return to Canada,” Montreal Star, 23 Nov. 1966.

[The author would like to thank Mr Luke Rombout, Dept. of Fine Arts, York University (Toronto), for information he supplied. r.v.]

Cite This Article

Raymond Vézina, “KRIEGHOFF (Kreighoff), CORNELIUS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 2, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/krieghoff_cornelius_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/krieghoff_cornelius_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | Raymond Vézina |

| Title of Article: | KRIEGHOFF (Kreighoff), CORNELIUS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | April 2, 2025 |