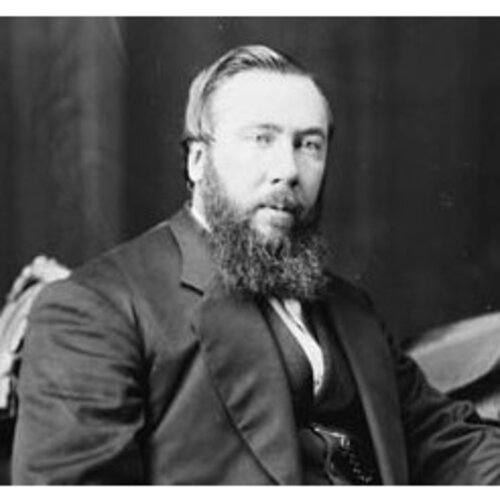

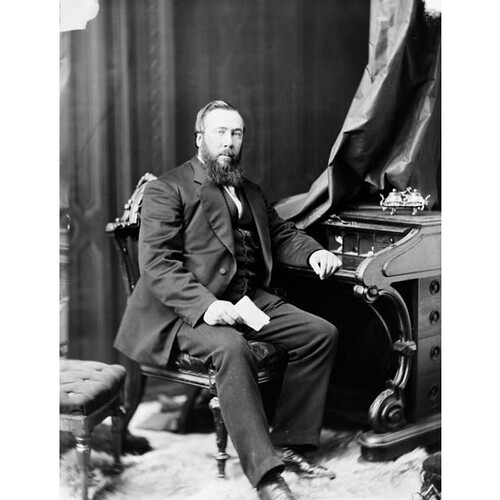

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

HOWLAN, GEORGE WILLIAM, businessman, politician, and office holder; b. 19 May 1835 in Waterford (Republic of Ireland); m. first 25 Oct. 1866 Elizabeth Olson (d. 1876) in Saint John, N.B.; m. secondly 22 Feb. 1881 Mary E. Doran in Kingston, Ont.; he had no children; d. 11 May 1901 in Charlottetown.

George William Howlan emigrated to North America with his parents in the late 1830s. They landed in Pugwash, N.S., but in 1839 moved to Prince Edward Island. Educated at Central Academy in Charlottetown, George began his business career there as a clerk in Henry Haszard’s store in 1850. In 1853 he moved to Cascumpec (Alberton) to work as clerk and agent for a Boston merchant named Captain Ryder. Within several years he was in business for himself. The thriving Island economy of the 1850s, in combination with Howlan’s investments in shipbuilding from 1853, established him as an increasingly wealthy merchant. Though he eventually eased himself out of shipowning, he would remain active as an entrepreneur until his death and would hold various business-oriented positions, such as consular official and vice-president of the Dominion Board of Trade.

Howlan’s business was only a small part of his life. His passion was politics, and after moving to Cascumpec he was careful to keep up on the political gossip from Charlottetown. In 1863 he stood for election to the House of Assembly as a liberal in Prince County, 1st District, and, though his party failed to win a majority, he was returned. Howlan entered a house – and a party – divided over the issue of religion in education. Since the mid 1850s the colony’s Protestants had been demanding that biblical instruction be made part of the school curriculum, a move opposed by the Catholics, who generally supported the liberals [see Peter McIntyre*; Edward Palmer*].

The atmosphere surrounding this and other issues of religion was often bitter, but Howlan, a Catholic who cast himself as a moderate, stressed in his first speech to the house that there could be common ground between Protestants and Catholics. Subsequently his stature in the legislature grew. In 1867, when the liberals returned to power under George Coles*, he was named to the Executive Council. The key to his power lay in the fact that his party’s Catholic members looked to him for leadership. The denominational strife of the previous decade had turned the liberals into a fragile coalition of Protestants and Catholics, and now Catholic support of the government would come only with a price.

In 1868 the matter of religion in the schools surfaced again as an issue. In response to the divisive question, the liberals had adopted the philosophy of strictly secular education. Howlan and the Catholic wing now argued that the school system was nondenominational in name only, contending that in fact it was run by, and geared to, the Protestant population. Alienated from it, the Catholics were operating schools of their own. “Were it not for the philanthropic efforts” of Bishop McIntyre of Charlottetown, Howlan maintained, “many of the children of that city would be wholly dependent [on] that education which is picked up in the streets.” If the colony was going to support what was, in effect, a Protestant school system, it should also be willing to fund a Catholic one. The colony’s liberal newspapers were appalled by this return to such a dangerous issue, and they held Howlan to blame.

The issue gained momentum as the liberals fell into increasing disarray. Coles was incapacitated by mental illness and the government’s day-to-day operations were directed by Attorney General Joseph Hensley*. In 1869, after Hensley accepted a position on the bench, the party selected Robert Poore Haythome* as leader and premier. The following year he led a deeply divided party into a general election. A confused affair, the election was fought on a number of issues, including education and confederation with the new dominion of Canada. Howlan simply called on the colony’s Catholics to vote for any candidate who favoured grants for Catholic schools. On election day the liberals polled a respectable majority but, in reality, to retain power they would have to reconcile their Protestant and Catholic factions.

On 18 Aug. 1870 Haythorne called his caucus to meet in Georgetown. Howlan’s demands were simple: backing for denominational schools in return for continued support. Haythorne’s Protestant members, however, were intractable, and after two days Howlan had had enough. He went to see the opposition leader, James Colledge Pope*, and offered an alliance between his Catholic liberals and Pope’s conservatives. The deal was struck, and on 10 September a government headed by Pope took office. Howlan seems to have been willing to give his new political allies more leeway on the school issue than he had allowed the liberals. Though Pope promised support for denominational schools, there is no grant listed in the public accounts for 1871 or 1872. Indeed, the issue was quickly forgotten as the administration began addressing the problems of confederation and the Island’s failing economy.

Howlan had demonstrated little interest in confederation before his alliance with Pope. During the crucial assembly debates of 1865 over the union of the colonies he opposed the notion. He felt the Island would have no voice in a federal parliament, and feared confederation would encourage the Canadians to go on a binge of canal and railway building “that Islanders would have to pay for.” Though unenthusiastic over confederation, he did recognize that the demise in 1866 of the Reciprocity Treaty with the United States would force the Island to make economic adjustments. “It is the duty of a government to bring forward every measure in their power which would open up trade and encourage industry,” he preached in 1867. Such measures, he became convinced, included the construction of an Island railway.

In 1869, when the possibility of a railway was first mentioned in the assembly, Howlan derided the idea as too expensive. By 1871, however, he maintained that “the colony could not afford to deny itself of the advantages which such a means of conveyance offer.” The struggle to pass the railway bill in the assembly demonstrated Howlan’s political skills and the delight he took in its rough-and-tumble. “If you are sick of talking about the railway,” he warned a friend in March 1871, near the beginning of the battle, “don’t get sick, for there is a good deal of talk to be done yet.” For the better part of a month he spearheaded the pro-railway force – cajoling, threatening, and, as it would later emerge, bribing potential supporters. By month’s end he was able to boast, “The battle is over and won. . . . We knocked the opposition higher than a kite.”

Though Howlan’s campaign was successful, some of his dealings would be exposed during the railway’s construction. One member charged that he had offered him £1,000 for his vote. Newspapers discovered that the station at Cascumpec was to be built on Howlan’s land. Premier Pope shrugged off these and other allegations of corruption, but, combined with mounting construction costs, they were enough to bring his government down. In the resulting election, in April 1872, Haythorne and his liberals returned to power.

Haythorne’s administration was to be short-lived, for the costs of the railway were running out of control. Debentures went unsold and the Island’s financial institutions were beginning to tremble under the strain. In April 1873 Haythorne was back before the voters, trying to convince them that the only way out of the predicament was to negotiate federal assumption of the Island’s debt. Howlan sheepishly agreed: “I have held anti-confederate views, but I find that no other course is now open to us . . . but to accept the best terms we can procure, and enter the Dominion.” The electoral platform of Pope and Howlan was uncomplicated: they had more friends in Ottawa, they argued, and could thus make a better deal than Haythorne, who had already begun discussions with federal authorities. A weary electorate agreed. Pope, Howlan, and Thomas Heath Haviland* went to Ottawa and completed the negotiations for the Island’s entry into confederation, which took place on 1 July 1873.

Howlan’s subsequent career was one of increasing honour but declining power. With entry into Canada, he believed, the Island’s legislature had become a political backwater. Mindful too, perhaps, of his financial security, he had accepted the collectorship of customs at Charlottetown in June. Eager to enter the federal political arena, he resigned in September to run in the special elections held that month to select the Island’s members of parliament. He lost in Prince, but in October he was appointed to the Senate. For reasons that are not clear, he later resigned for a short time (27 Dec. 1880–5 Jan. 1881). He found that being a senator, though attended by prestige, carried little real power. By 1884 he was ready to return to the Island, and was actively agitating for his appointment as lieutenant governor. He failed in his bid, partly as a result of the obstruction of Senator Jedediah Slason Carvell*. The following year he found an issue that offered a return to active politics.

Under the terms of confederation, the Island had been promised “continuous communication with the railway systems of the Dominion.” This commitment was difficult to keep, especially in wintertime, when the province was surrounded by ice. After the failure of a series of government-subsidized steamers, Islanders became convinced that the only secure link to the mainland would be a rail tunnel under the Northumberland Strait. Howlan seized on the issue and raised it in the Senate. In fact, he stood to make more than political points on a tunnel: in 1886 he formed a company to build the project in return for complete ownership of the Prince Edward Island Railway and an annual operating subsidy. His colleagues in parliament, however, were not listening, then or later. He decided he could do more for the project from the House of Commons, so he resigned from the Senate in February 1891 to run in the forthcoming general election. He campaigned in his old constituency, Prince County, but though the project was popular, Howlan was not. He went down decisively at the polls. His old friend Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald* reappointed him to the Senate in March. In 1894 Howlan was finally invited to become lieutenant governor of Prince Edward Island, an office he held until 1899. Two years later he died in Charlottetown.

George Howlan was described in Prince Edward Island illustrated as having “the social talents of a warm-hearted and highly intelligent Irish gentleman.” He was also a political operator of remarkable ability. For ten of the most critical years in Island history he was one of the colony’s most powerful politicians. Though he never led a party, he commanded a constituency that reached into every riding. In breaking with the liberal party he shattered the old alliance between the colony’s Catholics and reformers, and so reshaped Island politics. In engineering the passage of the railway bill of 1871, he fashioned the policy that would ultimately force the Island into confederation. He cannot be described as a visionary, for he probably never saw much beyond the immediate political expediency of his manoeuvres. His actions, however, had a far greater effect than those of many of his more famous contemporaries.

Memorial Univ. of Nfld (St John’s), Maritime Hist. Group, Atlantic Canada Shipping Project, Shipping registries of Prince Edward Island (microfiche; copy at PARO). PARO, Acc. 2851; Acc. 2654. PRO, CO 231/53–54. Examiner (Charlottetown), 11 May 1863; 3 July 1865; 23 April, 3 Sept. 1866; 29 March 1869. Islander, 26 Aug. 1870. Morning Guardian, 13 May 1901. Patriot (Charlottetown), 6 March 1869. Summerside Journal and Western Pioneer (Summerside, P.E.I.), 5, 8 Sept. 1870. Boyde Beck, “Tunnel vision,” Island Magazine (Charlottetown), no.19 (spring–summer 1986): 3–8. F. W. P. Bolger, Prince Edward Island and confederation, 1863–1873 (Charlottetown, 1964). Canadian annual rev. (Hopkins), 1901: 506. Canadian directory of parl. (Johnson). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). CPG, 1891: 51. Dominion annual reg., 1880–81: 257. P.E.I., House of Assembly, Debates and proc., 1867–69, 1871–72. Prince Edward Island illustrated (Charlottetown, 1897). I. R. Robertson, “Religion, politics, and education in P.E.I.” Vital statistics from N.B. newspapers, 1866–67 (Johnson), no.820.

Cite This Article

Boyde Beck, “HOWLAN, GEORGE WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 14, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/howlan_george_william_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/howlan_george_william_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Boyde Beck |

| Title of Article: | HOWLAN, GEORGE WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | April 14, 2025 |