Source: Link

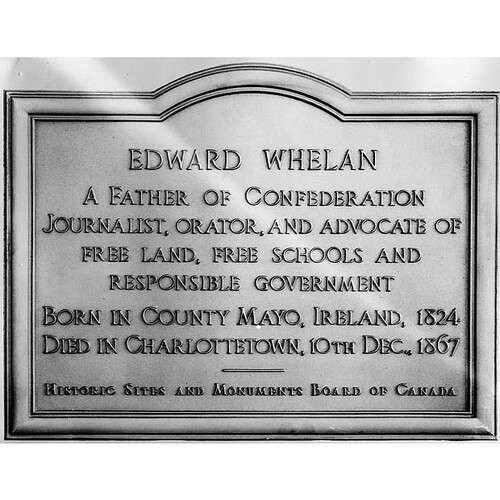

WHELAN, EDWARD, journalist and politician; b. 1824 at Ballina, County Mayo (Republic of Ireland), son of a soldier in the British infantry; d. 10 Dec. 1867 in Charlottetown, P.E.I.

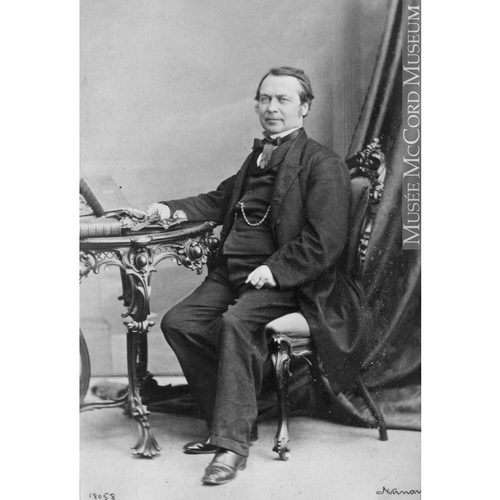

More than that of any other major figure in Prince Edward Island history, the early life of Edward Whelan is shrouded in romantic legend. He appears to have received a rudimentary education in Ballina and in Scotland before immigrating with his mother (who may have been widowed) to Halifax, N.S. In reply to insinuations by political enemies that they had arrived destitute, and that he had had to beg for his bread, Whelan wrote in 1855 that “enjoying in his mother’s right the fruits of no small amount of property, he was never placed in [an] abject condition.” According to the most precise account he has left, the year of their immigration was 1831, and he immediately enrolled in St Mary’s school. In the following year he was apprenticed in the printing office of Joseph Howe*, who encouraged him to continue his education through reading, as he himself had done. Thus Whelan spent his formative years at the intellectual centre of English speaking British North America: the Halifax of Howe, Thomas McCulloch*, Thomas Chandler Haliburton, and “The Club.” He eventually attended St Mary’s Seminary, and studied directly under its first superior, Father Richard Baptist O’Brien, a dynamic Irish priest, who commenced classes in January 1840. Both O’Brien and Howe profoundly influenced the precocious youth. In early 1842, against Howe’s wishes, Whelan left his office, where he had apparently remained during his studies at the seminary, and was ready, at age 18, to become an editor. Active in various Irish societies in Halifax, he succeeded O’Brien in directing the Register, an Irish Roman Catholic and Liberal newspaper strongly committed to repeal of the union between Ireland and England [see Laurence O’Connor Doyle]. While yet in his teens, he also became known as a speaker at the mechanics’ institute and at the Young Men’s Catholic Institute, an organization established by O’ Brien, a teacher of elocution and a well-known platform orator in his own right. One of Whelan’s later associates wrote that as an orator he was “brilliant, impassioned, exciting. He had the faculty of seizing at once upon the minds of his hearers, and carrying them along with him. . . . His language was always correct, well chosen, and gracefully delivered.” Writing several years after Whelan’s death, James Hayden Fletcher, himself an accomplished public lecturer, stated that “As a popular orator, we doubt if the Island has ever witnessed his equal.”

In early 1843 Whelan left the Register, hoping to start a new Liberal semi-weekly in Halifax. The prospectus he issued for the Spectator did not avow any specific ethnic or religious commitment. But the project miscarried, and that summer Whelan left Halifax for Charlottetown. Accounts by Peter McCourt, William Lawson Cotton, D. C. Harvey*, Emmet J. Mullally, and Wayne E. MacKinnon, appearing many years after Whelan’s death, assert that Island Reformers had consulted Howe on the choice of a journalist to found a newspaper independent of the local family compact, and that Howe had recommended the 19-year-old Irishman. This story, like so many others surrounding Whelan, appears to be apocryphal, for in 1855 he emphatically denied that he had come to the Island “under the auspices” of Howe. In any event, by mid June 1843 he was circulating a prospectus for the Palladium, a semi-weekly, in which he declared that his object would be “to investigate and assail, if not remedy, the evils which have grown out of the Landocracy System, a system whose principle is ‘monopoly,’ whose effect is oppression.” In his first number, on 4 Sept. 1843, he also pledged “not to outstep the line of demarcation prescribed by the constitution.” Edited with great gusto, the Palladium was a self-conscious advocate of local reform. Island Reformers had suffered defeat at the polls in 1842 following their failure to gain the acquiescence of the imperial government in their policy of escheat [see William Cooper]. The ideology of escheat was certain to come into question in this period of regrouping, and, while agreeing that the system of land tenure was pernicious, Whelan carefully avoided either becoming identified with escheat as a solution, or condemning it outright. He allowed Escheators access to his columns and admitted the justice of at least a partial escheat, but claimed that advocacy of a general escheat was impractical until responsible government had been obtained. This monumental reform, he argued, would provide the necessary leverage to force an end to leasehold tenure. Thus, from the beginning, Whelan tried to unify Island Reformers around the constitutional issue; although accepting the prevailing assumption that the root of the Island’s problems lay in the land system, he would not commit himself firmly on local matters over which Reformers might disagree, such as escheat or annexation to Nova Scotia as solutions to the land question.

Whelan later wrote that although he had not wished to make the Palladium “peculiarly Irish or Catholic in its tone,” a majority of his subscribers had been Irish Roman Catholics. This can probably be attributed to his vigorous advocacy of repeal. “Ireland will be a nation again. And where is the obstacle to prevent the accomplishment of her Nationality? English hatred and English jealousy.” References to “Saxon villainy and perfidy” may have restricted his readership, but Whelan adduced different causes for discontinuing the Palladium in May 1845. He expressed bitterness at the failure of Island Liberals to make good their promises of financial support, despite a steadily increasing subscription list. Nineteen months of publication had left him with some £400 in bad debts. Deeply disillusioned, Whelan decided to leave the Island, and indeed there was a discernible slackening of interest in local news throughout the last months of the Palladium. He devoted the rest of 1845 to winding up its affairs, but, because of unforeseen circumstances, he remained on the Island several more months. To the surprise of many, he was named editor of the previously Tory Morning News in May 1846. The reasons for his appointment are not known with certainty, but it was probably linked to a growing rift between the local oligarchy and Lieutenant Governor Sir Henry Vere Huntley. The publisher of the News, E. A. Moody, leaned towards Huntley; Whelan, for his part, believed the Reformers could exploit the feud for their own benefit. Consequently the Morning News became the organ of liberal reform on the Island until Moody’s death in October. Apparently alarmed at the success of the News, which then had the largest circulation of any Island newspaper, the compact seems to have bought the press, thus depriving Whelan of his new editorial chair.

Yet in August 1846 Whelan had cemented his connection with the Island by gaining election as an assemblyman for St Peters in Kings County, at age 22. In his nomination speech at Grand River he stated that “the numerous slanders” of “my Charlottetown enemies” had been an important factor in his decision to contest the election. He was, in the words of one contemporary, “hated and sneered at by his opponents . . . [and] also feared. . . . In fact, like [Daniel O’Connell] he was the best abused man of his day.” More than once over the years Whelan would return to this theme: “the desire for retaliation has given us more than anything else a personal interest in the struggle, from gratifying which no sacrifice or inconvenience will deter us.” It was this fighting spirit which made his newspapers such effective journaux de combat; it also brought him before the courts several times, on charges of trespass, “riot and assault,” and both civil and criminal libel. At least once, in 1850, he was a successful plaintiff in an assault case. Although he remained an assemblyman until the last year of his life, he never developed into a great parliamentarian. His attendance was sporadic, his interventions in most years were infrequent, and the debates never seemed to awaken in him the genius and passion apparent in his printed work. Perhaps this lack is a reflection of the fact that Whelan was always more artist than logician. In any event, the press remained his primary forum. Over the years in Charlottetown, Whelan was also a leading member of such community organizations as the mechanics’ institute, the Charlottetown Repeal Association, the Benevolent Irish Society, and the Catholic Young Men’s Literary Institute.

Even before Moody died, Whelan had decided to establish a new publication, one he would fully control and which would guarantee his security of tenure. He circulated a prospectus for a weekly, the Examiner, in the autumn of 1846, but was, according to Huntley, refused access to the existing presses “upon any terms; the Compact forbade it.” The plant he purchased in Boston did not arrive before the close of navigation, and hence the first number of the Examiner did not appear until 7 Aug. 1847. The biting wit and brilliant writing of the Palladium remained, but two differences were immediately apparent: a general moderation in tone and a lack of concentration on Ireland. Indeed there was no editorial commentary on Ireland, apparently the result of a calculated decision to broaden the audience to which he appealed. The sensitivity of the Irish question became apparent when, on 16 Oct. 1848, with Ireland in a state of semi-insurrection and state trials being held, Whelan finally broke his silence. Although criticizing the rebel leaders for incapacity and bad judgement, he declared his faith in the justice of their cause. Their fault was that they had blundered into “beginning a war of independence, which they had neither men nor money to sustain . . . we cannot but regret, that such men ever espoused such a cause, or having espoused it, they did not succeed.” He expected them to be convicted of high treason, given that they were being tried by “partizan judges . . . and a partizan jury.” These were strong words, and the editorial was gleefully reprinted by the Tory Islander and Royal Gazette. Such leading local Liberals as William Swabey* (who was rumoured to have paid for the purchase and importation of the Examiner’s press) and Alexander Rae quickly dissociated themselves from Whelan’s sentiments. The controversy over his brief resumption of commentary on Ireland may have been a cause of the Examiner’s suspension of publication between February 1849 and January 1850; the ostensible reason was once again the failure of subscribers to pay.

Whelan’s moderating of his tone was of a piece with the orientation of the Reform forces in P.E.I. in the late 1840s. With George Coles* firmly in command, moderation took control. Indeed in the third number of the Examiner Whelan drew an explicit distinction between “the Liberal Party, as now constituted,” and “the old Escheat party.” The break was more than a matter of semantics. In the columns of the Examiner responsible government replaced the land question as the focus of agitation. Constitutional change was often presented as a goal for its own sake or as a general panacea, rather than as a prerequisite to solution of the land question. In emphasizing this lowest common denominator of reform, Whelan was probably drawing upon his first-hand knowledge of the recent history of Nova Scotia, where Reformers had been slow to find a common platform. It was the peculiar virtue of Whelan as a strategist that he recognized the need, if the Reformers were to gain power by parliamentary means, to focus on an issue which would bring together the diverse Reform constituencies of the colony. In this respect, he and Coles displayed greater political acumen and resolution than Howe. Part of the reason must have been that Whelan, as an Irish Roman Catholic immigrant, had fewer inhibitions about challenging the status quo than did Howe, the reverent son of a loyalist.

The struggle for responsible government grew in intensity in 1850, particularly after the electoral victory of the Reformers in February, and the subsequent refusal of the lieutenant governor, Sir Donald Campbell*, to accede to their demands. Throughout the year Whelan relentlessly hammered away at the issue. He spoke at numerous public meetings, and in late February decided to publish on a semi-weekly schedule in order to reach the public more frequently. In this highly charged atmosphere of confrontation, the Examiner was indispensable to the Reform cause in explaining and popularizing the idea of responsible government. By the time it was attained, Whelan’s stature in the Reform movement was second only to that of Coles. Hence it was no surprise that in April 1851 the 27-year-old journalist was named to the first Executive Council formed on the principle of responsible government. In July he was also appointed queen’s printer, despite intense indignation on the part of the incumbent of 21 years’ standing, James Douglas Haszard*. Whelan held the position until 1859 (with the exception of several months in 1854) and again in 1867. He discontinued publication of the Examiner and made the hitherto rather staid Royal Gazette into something much more than a vehicle for official notices and proclamations. “Of all papers the Gazette should, in our estimation, be the political paper.” The Gazette was to be the defender of the Liberal government par excellence, and thus was in every sense the successor of the Examiner, which was not resurrected until early 1854.

Whelan played a leading role in explaining and defending the major Liberal reforms of the 1850s: the Free Education Act, extension of the franchise, and the Land Purchase Act. As a good 19th century liberal he believed that these measures, through increasing the common Islander’s educational attainments, political rights, and chances of becoming a freeholder, would enhance the political development, social stability, and economic prosperity of the community as a whole. Yet when the land reform programme of the Liberals proved inadequate for the task confronting it, Whelan shared Coles’ reluctance to advocate more drastic measures. Indeed in the mid 1850s he polemicized at length with the old Escheators, who were growing restless. The other serious problem for the Liberals in the late 1850s was the dispute over the proper place of the Bible in the educational system. Whelan, always acutely aware of the dangers of religious squabbling in a mixed community, was appalled by the tenor of the campaign waged by Protestant militants for legal authorization of Bible reading in the district schools. He responded with a barrage of ridicule and invective in the Examiner, at one point portraying their organ, the Protector and Christian Witness, as rushing about with “a Bible in one hand and a bludgeon in the other . . . like a big bully . . . [who] while breaking the bones of his victims with the one, pretends to be very desirous of healing the wounds of the spirit with the other.” Yet despite Whelan’s wit and Coles’ hard campaigning, the Bible question brought down the Liberal government in 1859.

The Liberals did not adapt quickly to their return to opposition. In the autumn of 1859 Whelan wrote that the party “appears to be without a leader, has lost heart, and is thoroughly cowed.” Whelan himself provided little leadership: he was absent from the assembly much of the time, and in 1861 self-consciously commented: “I seldom trouble the House with my remarks.” Yet as the politico-religious polemics between William Henry Pope* and David Laird* on the one side, and Father Angus MacDonald* on the other, rekindled the political atmosphere in 1861–62, Whelan became actively involved in the defence of MacDonald and Bishop Peter MacIntyre*, and attacked “Pope’s Epistles Against the Romans.” In the course of the controversies, the Vindicator, an ultramontane newspaper, was founded in Charlottetown, published by Edward Reilly*, a former employee of Whelan, and reputedly edited by MacDonald. In its first number, although conceding that Whelan was a Roman Catholic and had opened his columns to Catholic arguments, it stated rather ominously that “the Examiner is not a Catholic newspaper.” The religious polarization of this period provided the basis for the successful Conservative campaign of 1863.

After the election, religious issues receded in importance. When union of the British North American colonies arose as a question of the day, the Tory government became hopelessly divided between supporters and opponents of confederation. The Liberals were in a position to profit from this situation, for they reflected the distaste of Islanders as a whole for confederation. The sole notable exception in their ranks was Whelan. Immediately prior to the Charlottetown conference he had expressed scepticism about the prospects for union, especially if it involved abolition of local legislatures. But by 5 September he was enthusiastic about the project, particularly because “a union will relieve us from the provoking intermeddling of the Colonial Office in our local legislation. . . . And what is still more gratifying to contemplate, proprietary influence at the Colonial Office would be . . . driven to the wall.” Whelan was selected to be one of the delegates to the Quebec conference. Although not satisfied with the provisions for representation of the Island in federal legislative bodies, he remained an advocate of union, and vigorously promoted it in the columns of the Examiner. He also began to compile a collection of banquet speeches given in connection with both conferences, which he published in 1865. But as it became apparent that his advocacy was having little effect, Whelan grew increasingly disenchanted with “the petulance of this little place.” When the Quebec resolutions were debated in the assembly, Coles pointedly remarked, referring to his long-time colleague, that “There are fewer old party ties to bind us now than formerly.” During the debate on James Colledge Pope*’s “no terms” resolutions of 1866, Whelan complained that “I never, in the course of my parliamentary experience of 20 years, was made the subject of so much calumny – so many false accusations, as in reference to this question.”

The other major issue which dominated the mid 1860s was once again the land question. With the failure of the Tories to make significant progress towards abolition of leasehold tenure, the Tenant League, a society sworn to withhold rents, arose. In the summer of 1865 the Tory government was sufficiently alarmed by the activities of the league, and the inability of the local authorities to deal effectively with it, that they summoned troops from Halifax. They also systematically purged the ranks of district teachers and magistrates of league sympathizers. Whelan’s attitude towards such an organization had gone through several stages, reflecting the ever-present tension within him between the British liberal and the Irish radical. When an abortive tenant league had emerged in 1850–51, inspired by a tenants’ movement in contemporary Ireland, Whelan refused to condemn it categorically, and had simply labelled it “premature”; writing hypothetically in 1855, he had emphatically denied that the government should raise or call upon special forces to assist civil authorities in the collection of rents; and as late as the autumn of 1860, when land agents were collecting rents at harvest-time with unusual zeal and the tenants were exhibiting acute restlessness, Whelan, while not counselling nonpayment, nonetheless advised the tenantry to organize, on democratic principles, centrally directed “Mutual Protection Societies, or Tenant Leagues” which would be necessary if they were “to be prepared, as a united people, for any emergency that may arise.” He reminded his readers that what “was criminal on the part of the few poor devils who were too weak to carry their point, becomes praiseworthy and heroical with the many who are strong enough to bear down all opposition.” But by the time serious disturbances arose in the mid 1860s Whelan had cut himself off from the tenants’ movement, and was firmly committed to parliamentary means. He vigorously attacked the league, defended the use of troops, and indeed argued that the government should have suppressed it upon the publication in 1864 of its “dishonest and seditious pledge” in Ross’s Weekly. Consequently, he became detested by the Leaguers, who no doubt remembered his earlier views, and whose leaders, such as George F. Adams, urged them to withdraw their subscriptions from the Examiner. Together, the land question and confederation ensured the defeat of the Conservatives in 1867. The Liberals, with one significant exception, had opposed confederation, and although not Leaguers, neither were they proprietors nor their agents. These two issues had also left Whelan largely isolated within his own party.

Although the Liberals had won decisively in 1867, victory brought its own problems. The question of the Tenant League, whose withholding of rents Coles had also opposed, had created a deep fissure between radicals and “Old Liberals.” Whelan especially had suffered from this division, and the radical Liberal members were not disposed to return the queen’s printership to him. Nonetheless, after a caucus debate which lasted two days, the “Old Liberals” won this test of strength, and Whelan was restored to his former office. The difficulty was that its acceptance obliged him to resign his seat in the assembly and to contest it again. Although he had won every previous election over a period of 21 years, he lost the by-election to Reilly, who was then editor of the Charlottetown Herald. He nevertheless remained queen’s printer, for Reilly refused to accept the post on the condition of running for re-election.

There is no single cause or explanation for Whelan’s defeat. His denunciations of the Tenant League and Fenianism (which he called an “infamous conspiracy”) had cost him support among his traditional followers, i.e. leaseholders and Irish Roman Catholics. His advocacy of confederation was equally damaging. In 1867, anti-confederacy was a virtual test of fitness for the local legislature, and Whelan was the only prominent heretic in a party which was sound. On each of these three issues Reilly had the advantage: he had espoused the tenants’ cause with single-minded vigour, was non-committal on Fenianism, and was unequivocally opposed to confederation, over which he had polemicized with Whelan since 1864.

But, for Whelan, the decisive cause of his defeat was to be found elsewhere. Two days before the election he wrote that “there would not be the shadow of a doubt about the matter if the Catholic electors, who are the majority of the voters, were not subjected to unseen influences that cannot be easily met and overcome.” After his loss he charged that Reilly had “had a most unscrupulous person of a certain clerical ‘order’ to canvas for him incessantly.” He was undoubtedly referring to Father William Phelan, recently arrived from Ireland, a friend and partisan of Reilly, who had just displaced Father Ronald Bernard MacDonald in St Peters parish. According to the Roman Catholic historian Father John C. Macmillan, MacDonald “was well known to be a personal friend of Mr Whelan,” and many believed that his timely removal after only a few months’ service at St Peters was a sign of Bishop MacIntyre’s displeasure with the queen’s printer.

The reasons for the bishop’s disapproval are obscure but nonetheless important. In the first place, Whelan’s advocacy of confederation had made him an ally of William Pope, the most tenacious Island confederate and the bête noire of Island Catholicism. Secondly, Bishop MacIntyre was a crusader for total abstinence from alcoholic beverages, and Whelan, the leading Roman Catholic public man in the colony, was something less than an exemplar for the masses in this respect. One of his former reporters, Thomas Kirwan, would write in an obituary article that “he was a fast liver, and fast livers do not generally attain to patriarchal age.” But perhaps most important was a factor noted by Macmillan: “A rumor . . . was in the air, that Mr. Whelan had grown somewhat indifferent in matters of faith, and had been for a time utterly neglectful with regard to the practices of his religion.” Rumours of this nature concerning Whelan had been circulating for many years, fuelled on at least one occasion by his own remarks in the assembly. At this remove it is impossible to determine the truth with any precision; yet some lack of orthodoxy may be inferred from the fact that his second marriage, on 21 Oct. 1850 to Miss Mary Major Hughes, was performed by a clergyman of the Church of England. Thus, for a number of reasons, it seems likely that relations between Whelan and the bishop were strained. Indeed, the Vindicator, which appears to have been the organ of the Roman Catholic clergy, had been a conscious rival of Whelan for the attention of Island Catholics. In 1867 Bishop MacIntyre, an ardent and energetic ultramontane with little patience for dissenting views, was in all probability mobilizing his forces in order to gain public financial support for his educational institutions. In early 1868 he would present a memorial to the Coles government for such assistance. Whether Whelan would have supported anything more than a grant to St Dunstan’s College is dubious, since he was an initiator of the secular Free Education Act, had publicly denied that Catholics were bound to accept political direction from ecclesiastics, and in 1860 had declared that “clergymen are generally the most incompetent persons in the world to have anything to do with the administration of secular affairs.” It is true that in 1851 he had advocated public assistance for a Roman Catholic school in Charlottetown, but it had then become subject to the standard district school regulations; and throughout the succeeding years Whelan had repeatedly expressed his belief that separate schools would only entrench religious and national prejudices.

In any event, Whelan was convinced that his defeat had been owing to undue clerical influence. In September he noted with evident satisfaction the failure of Archbishop Thomas Connolly*’s manifesto in favour of confederation. “We hope this complete overthrow of his Grace’s influence in the political world will be warning to all ecclesiastics everywhere not to meddle too much in political affairs.” Apparently he never recovered from the bitterness of the defeat, which was the culmination of several unpleasant turns in his political career. Over the summer and autumn of 1867 his health slowly deteriorated. On 10 December he died at age 43, a broken man. The cause of death was given as dropsy. His obituary in the Examiner said that his “mantle, we fear, falls on no man.” This was true in two respects: Prince Edward Island was never to know a more talented journalist, and the Roman Catholic laity did not for many years find another leader of his stature.

Whelan has become known as a romantic, even tragic figure, and deservedly so. Not only did he die before his time, a disappointed man, but, some five months after their marriage, his first wife, Mrs Mary Weymouth, a widow 11 years his senior, had died on 15 Oct. 1845 following the birth of a boy who also appears to have died shortly afterwards; his two daughters by his second marriage predeceased him; and his son Edward, the only child to survive him, later perished in a drowning accident on Dominion Day, 1875, at age 20, on the threshold of a promising career in journalism. On the day before his death he had been awarded a prize for English composition at St Dunstan’s College. The Island Argus reported that the son’s funeral was “one of the very largest ever witnessed in Charlottetown. The name of the Hon. Edward Whelan is still cherished by the people.” In 1900 the same writer, J. H. Fletcher, would recall that, growing up a Liberal in Prince Edward Island, he had read every word of every number of the Examiner and had come to believe “that its editor was the greatest man that lived on the Island. And I am still of the same opinion.”

Edward Whelan’s historical reputation has rested primarily on his contribution to the struggle for responsible government, and on his advocacy of confederation at a time and in a place where that cause was intensely unpopular. His role in each case reflects well on his political courage and tenacity, but it was undoubtedly in the former that he was more effective, and his behaviour in it deserves the more careful analysis, both in terms of Island history and for an understanding of his career as a whole. In the 1840s he had come to Prince Edward Island as a remarkably precocious young man, and effectively mobilized the newly settled Irish tenantry behind the Reform cause. At the same time he played what was probably a decisive part in moderating the demands of Island Reformers, suppressing points of difference, and creating the unified movement of which George Coles would assume leadership. Although no one was more aware than Whelan, the Irish immigrant, of the land question’s importance, his strategy was “responsible government first.” Yet after constitutional reform had been won, the land question continued to bedevil the colony, and since gradualism seemed to have exhausted its potential, Whelan’s constituency began to drift towards radical solutions and direct action in the countryside, which he ultimately rejected. Contemporaneously, Irish nationalists, particularly in the exile communities, were becoming more willing to countenance violent methods. Whelan, who had begun his journalistic career in Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island by appealing primarily to Irishmen, and whose strength had been his uneasy synthesis of British liberalism and Irish radicalism, suffered from this split in the Irish movement. He became more and more of a liberal constitutionalist in his later years, and grew increasingly impatient with radicalism whether at home or abroad. This isolation from the original sources of his strength in public life, when combined with his adherence to the confederate cause and his problems with the Roman Catholic clergy, led to his political downfall and hastened his death.

[Edward Whelan’s private papers perished in a fire at his former residence in 1876. But his newspapers and the records of proceedings in the Island assembly provide a comprehensive and detailed picture of his views. For the assembly debates see: Royal Gazette (Charlottetown), 1847–53; Islander, 1854; and P.E.I., House of Assembly, Debates and proc., 1855–66. The following years of his newspapers have survived to a greater or less degree: Register (Halifax), 1843; Palladium (Charlottetown), 1843–45; Morning News (Charlottetown), 1846; Examiner (Charlottetown), 1847–51, 1855–67; and Royal Gazette, 1851–59, 1867. From August 1854 on his Royal Gazette resumed a traditional character. The author believes that Peter McCourt, in his Biographical sketch of the Honorable Edward Whelan, together with a compilation of his principal speeches; also interesting and instructive addresses to the electors . . . (Charlottetown, 1888), 10, and D. C. Harvey, The centenary of Edward Whelan: lecture delivered in Strand Theatre, Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, August 9,1926 (n.p., n.d.; republished and more accessible in Historical essays on the Atlantic provinces, ed. G. A. Rawlyk, (Toronto, 1967)), 214, were wrong in stating that Whelan published the short-lived Reporter (Charlottetown) of 1847; nonetheless, it appears that he may have been its editor. There is no evidence to sustain the story Thomas Kirwan repeated in an otherwise excellent obituary article in the Summerside Progress (Summerside, P.E.I.), 16 Dec. 1867, that “Mr. W.’s first essay in publishing was made in one of the western towns of Nova Scotia.” Important articles and letters from the Morning News (Charlottetown) of 16, 20, 23, 27 May 1846 will be found in McCourt, Biographical sketch . . . , 5–10, and in PRO, CO 226/69, 345–51.

The following individual numbers of newspapers are particularly useful for a study of Whelan’s career: Colonial Herald (Charlottetown), 17 June 1843. Constitutionalist (Charlottetown), 9, 23 May, 6 June, 5 Sept., 3, 10 Oct. 1846. Examiner, 7, 14, 21 Aug., 18 Dec. 1847; 26 June, 31 July, 14 Aug., 11, 18 Sept., 16, 23, 30 Oct., 13 Nov. 1848; 1 Jan., 12 Feb. 1849; 12 Jan., 23 Feb., 2, 13 March, 3 Aug., 23, 30 Oct., 6, 9, 20 Nov., 11 Dec. 1850; 8, 11 Jan., 14, 28 April, 13 May, 7 July 1851; 18 June, 10 Dec. 1855; 14 July, 8 Dec. 1856; 19, 26 Jan., 2, 9 Feb., 13 July 1857; 7, 28 June, 19 July 1858; 12, 26 Sept., 3 Oct., 26 Dec. 1859; 11 Sept., 23 Oct., 5, 12 Nov., 17 Dec. 1860; 7, 14 Jan., 4 Feb., 20 May, 10, 24 June, 22 July, 5, 26 Aug., 16, 23 Sept. 1861; 17 March, 23, 30 June, 22 Sept., 10 Nov. 1862; 19 Jan., 9 Feb., 23 March, 24, 31 Aug., 16 Nov., 14 Dec. 1863; 4, 11, 25 Jan., 1 Feb., 2, 23, 30 May, 5 Sept., 17 Oct., 21 Nov., 26 Dec. 1864; 24 April, 12, 19, 26 June, 10, 24 July, 7, 21 Aug., 16 Oct., 13 Nov., 18 Dec. 1865; 12 March, 4 June, 16 July, 1 Oct., 10 Dec. 1866; 4 Feb., 18 March, 15, 29 April, 6 May, 16, 23 Sept., 16 Dec. (obit.), 30 Dec. 1867; 5 July 1875. Express and Commercial Advertiser (Charlottetown), 9 Nov. 1850. Herald (Charlottetown), 28 Dec. 1864; 24 April, 18 Dec. (obit.), 25 Dec. 1867; 8 Jan. 1868. Island Argus (Charlottetown), 6, 13 July, 21 Sept. 1875. Islander, 8 Sept. 1843; 18 Oct. 1845; 20 March 1847; 6, 20 Oct. 1848; 12 July, 8 Nov. 1850; 30 April 1852; 8 June 1855; 4 Jan., 3 Oct. 1856; 6 Jan. 1860; 23 Aug. 1861; 15 Jan. 1864; 26 April, 3 May, 13 Dec. (obit.) 1867; 15 Jan. 1869. Morning News (Charlottetown), 11, 15, 22, 29 April, 3, 10 June, 26 Sept., 3 Oct. 1846. Palladium (Charlottetown), 4, 7, 11, 14, 25 Sept., 16, 30 Nov., 14, 28 Dec. 1843; 4 Jan., 29 Feb., 21 March, 11, 25 April, 23 May, 27 June, 4, 11 July, 3, 10 Oct., 16 Nov., 21 Dec. 1844; 29 March, 19 April, 3 May 1845. Patriot (Charlottetown), 12 Dec. 1867 (obit.); 3, 8, 15 July 1875. Protestant and Evangelical Witness (Charlottetown), 12 Nov. 1864. Register (Halifax), 10 Jan., 25 April, 2 May 1843. Royal Gazette (Charlottetown), 5 Sept. 1843; 6, 13 May, 21 Oct. 1845; 24 Oct. 1848; 16 July 1850; 11 March, 14 July 1851; 23 Feb., 15 March, 26 April, 3, 24 May 1852; 24 Oct., 7 Nov., 26 Dec. 1853; 1 Aug. 1854; 22 March 1855; 26 Dec. 1867. Summerside Journal (Summerside, P.E.I.), 12 Dec. 1867 (obit.). Summerside Progress (Summerside, P.E.I.), 25 March, 23 Dec. 1867. Vindicator (Charlottetown), 17 Oct. 1862.

For some of Whelan’s more important contributions to debates in the assembly, see Royal Gazette, 2, 16 March, 13 April 1847; 22 April 1851; 29 Jan. 1852; 7 March 1853. Islander, 28 Feb. 1854. P.E.I., House of Assembly, Debates and proc., 1855, 35–38, 66; 1856, 27; 1857, 61–63; 1859, 63, 82, 86–88; 1860, 15; 1861, 16, 40–41, 135; 1862, 16; 1863, 44–45; 1864, 56–59; 1865, 7; 1866, 42, 107, 120; also see 1868, 147.

Whelan’s compilation of speeches surrounding the Charlottetown and Quebec conferences appeared under the title The union of the British provinces: a brief account of the several conferences held in the Maritime provinces and in Canada, in September and October, 1864, on the proposed confederation of the provinces, together with a report of the speeches delivered by the delegates from the provinces, on important public occasions (Charlottetown, 1865; repr. Summerside, P.E.I., 1949). Several of Whelan’s addresses, both in and out of the assembly, are reproduced in McCourt, Biographical sketch. . . . McCourt’s collection contains an account of Whelan’s life. Whelan has been the subject of two shorter studies: Harvey, The centenary of Edward Whelan, and E. J. Mullally, “The Hon. Edward Whelan, a father of confederation from Prince Edward Island, one of Ireland’s gifts to Canada,” CCHA Report,1938–39, 67–84. Neither is fully reliable, and even the better, by Harvey, leans too heavily on McCourt, particularly concerning Whelan’s early years, and consequently reproduces his factual errors.

See also: PAPEI, P.E.I., Land Registry Office, Land Conveyance Registers, liber 54, f.390. P.E.I., Supreme Court, Estates Division, liber 7, f.399 (will of Edward Whelan, 7 Dec. 1867) (mfm. at PAPEI). PAC, MG 26, A, 338, pp.154610–16. PANS, MG 20, 67. PRO, CO 226/69,324–35; 226/71,67–76; 226/72, 109–10; 226/75, 17–21; 226/100, 231–32. C. T. Bagnall, “A name which sends our thoughts back to the old time,” Prince Edward Island Magazine (Charlottetown), 4 (1902–3), 351–53. F. W. P. Bolger, Prince Edward Island and confederation, 1863–1873 (Charlottetown, 1964), chaps. 1–8. W. L. Cotton, “The press in Prince Edward Island,” Past and present in Prince Edward Island . . . , ed. D. A. MacKinnon and A. B. Warburton (Charlottetown, [1906]), 116. J. H. Fletcher, “Newspaper life and newspaper men,” Prince Edward Island Magazine (Charlottetown), 2 (1900–1), 69–70. A. A. Johnston, A history of the Catholic Church in eastern Nova Scotia (2v., Antigonish, N.S., 1960–71), II, 160, 166–67, 179–80, 215. W. E. MacKinnon, The life of the party: a history of the Liberal party in Prince Edward Island (Summerside, P.E.I., 1973), chaps. 2–4. J. C. Macmillan, The history of the Catholic Church in Prince Edward Island from 1835 till 1891 (Quebec, 1913), chaps. 9, 11, 14, 16–17, 19–20. Robertson, “Religion, politics, and education in P.E.I.,” chaps. 1–7, and pp.315–16. [Edward Whelan], “Edward Whelan reports from the Quebec conference,” ed. P. B. Waite, CHR, XLII (1961), 23–45. i.r.r.]

Cite This Article

Ian Ross Robertson, “WHELAN, EDWARD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 24, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/whelan_edward_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/whelan_edward_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | Ian Ross Robertson |

| Title of Article: | WHELAN, EDWARD |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1976 |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | December 24, 2025 |