Source: Link

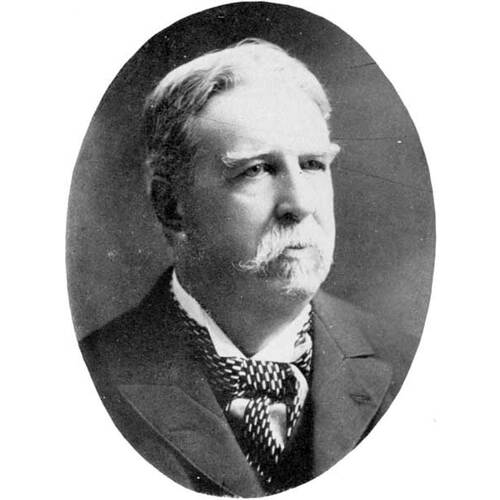

WHEELER, CHARLES HENRY, architect, musician, choirmaster, and music and drama critic; b. 1838 in Lutterworth, England; m. 9 May 1859 Annie Wakefield in Coventry, England, and they had seven children; d. 7 Jan. 1917 in Winnipeg.

From his early years Charles Wheeler’s interest in architecture was encouraged by his parents. He was apprenticed in carpentry, bricklaying, painting, and stonemasonry, acquiring fundamental skills. He also learned pattern-making at the Coventry Engine and Art Metal Works. For 20 years his career in Great Britain included assignments as construction foreman, clerk of works (project supervisor), and architect on churches, mansions, and bridges. In addition, he had a two-year contract with the British government to supervise construction of a jail in Shanghai. He spent some time working for noted British architect George Edmund Street of London and for the well-known firm of William Martin and John Henry Chamberlain in Birmingham.

After reading a glowing account of the opportunities on the Canadian prairies, Wheeler decided to emigrate. He arrived in Winnipeg with his wife and six children in late February 1882, after the peak of a frenzied land boom [see Alexander Logan*]. He first came to the notice of Winnipeggers through his interest in music. On 19 April it was announced that he would perform as a bass soloist during a recital at Holy Trinity Anglican Church. The event was billed as the “richest musical treat of the season.”

Holy Trinity awarded prizes for the design of a new church building in the spring of 1883, but Wheeler, who had submitted a proposal, was not among the winners. Shortly thereafter, however, a new call for tenders was issued at a revised cost of $60,000. The chosen proposal was that entered by James Chisholm and Wheeler. Wheeler worked with Chisholm for a brief time to acquaint himself with methods of construction on the Canadian prairies, but the drawings for Holy Trinity, in Gothic style, are in his hand and he is acknowledged as its architect. Under his supervision, construction was completed in July 1884. The design, based on early-13th-century English churches, introduced a restrained, British academic style of architecture to the conception of places of worship in the city. It attested to Wheeler’s reputation as a skilled professional architect who brought respectability and vitality to Winnipeg.

In the fall of 1884 controversy arose over the construction of Winnipeg’s new city hall, being built according to the plans of Wheeler’s rivals Barber and Barber [see Charles Arnold Barber]. Wheeler, hired as examining architect, disapproved of the contracts drawn up by the Barbers and of their methods of heating, plumbing, and specifying materials. After the Barbers were dismissed from the project, Wheeler and Chisholm were appointed to superintend its completion.

Wheeler was commissioned in 1887 to design a brick and stone warehouse for the firm G. F. Galt and J. Galt, wholesale grocers [see George Frederick Galt*]. It is the earliest local example of Wheeler’s use of Romanesque Revival detailing for a commercial building; he would apply this type of exterior ornamentation to the majority of his subsequent projects. The lower level of the warehouse is of rusticated stone which supports giant pilasters that rise three storeys, giving a distinct bay-by-bay division. Wheeler’s typical window plan is clearly articulated: large round-headed windows on the main floor are broken down into pairs on the second floor and triplets on the third. Elaborate brick corbelling was used to finish the building. The entrance way was set at the corner, creating the effect of a tower. All the windows have a stone sill and hood mould for additional articulation.

By 1889 Wheeler, assisted by two of his sons, Alfred Harry and Charles William, had the busiest architectural firm in the city. Projects included the Deaf and Dumb Institute in Winnipeg, the Home for Incurables in Portage la Prairie, and the Merchants’ Bank of Canada in Brandon, all in 1890, as well as business blocks in Regina, Methodist churches in Moosomin (Sask.) and Morden, Man., and numerous residences and warehouses. Throughout the 1890s he continued to receive many prestigious commissions. For the province he designed an insane asylum (1892) in Brandon and won a competition for the court-house (1893) in Winnipeg. The court-house displayed the Romanesque Revival style, but with the added touch of a red brick finish and limestone highlights. This same style was used for two identical buildings – the Argyle Street and Dufferin schools – which Wheeler planned in 1896 for the Winnipeg School Board. In 1895 he had designed a new Romanesque Revival home for former mp Hugh John Macdonald*. Preserved as a local museum, Dalnavert shows Wheeler’s skill as an architect and his commitment to honesty in his work.

Towards the end of the 1890s a change occurred in architectural practice in Winnipeg. While local architects were designing a variety of buildings in the northwest, important commissions for projects in the city began going to Toronto-based architects. Resident professionals were hired to supervise construction. One of Wheeler’s last major projects was the supervision of a new building for the Canadian Bank of Commerce designed by the Toronto firm of Frank Darling* and John Andrew Pearson*. Wheeler’s architectural practice continued until 1906, the majority of commissions being residences or small additions to buildings he had previously designed. He became second vice-president of the Manitoba Association of Architects at its formation on 25 May 1906.

Wheeler, a self-described “ardent Gothicist,” was influenced by art critic John Ruskin. Consistent with Ruskin, Wheeler held that the exterior decoration of a building must suit its intended use and that the designer must pay attention to proportion, symmetry, and fitness. Wheeler’s approach to design can best be summed up in a description of one of his residences, where there was “no superfluous ornament, every feature is in its proper place and a most pleasing appearance is produced.”

For Wheeler, music and drama were as important as designing buildings. He had probably studied music in Coventry and is known to have written a music column for several weeklies in London. On his arrival in Winnipeg he established himself as a professor of music and immediately became a soloist and choirmaster. Music and drama, as well as architecture, were undergoing profound changes in the 1880s. Amateur performances and variety theatres gave way to melodrama, as travelling stock companies from central Canada and the United States began to arrive in the city [see William Blake Lawrence]. Serious music could be found only in certain churches which imported salaried organists from central Canada, had large choirs, and installed new pipe-organs. Wheeler had joined the choir of Holy Trinity Church shortly after his arrival in 1882, but within months he became choirmaster of Zion Methodist Church. In March 1885 he took over the choir at Knox Presbyterian Church after helping that congregation resolve claims against its contractor.

He started writing critical reviews of Winnipeg’s musical and theatrical events in 1883, submitting articles to various city newspapers. About 1887 he was hired by the Sun and wrote for approximately three years. His Saturday column on music and drama in the Winnipeg Tribune started in 1890 and continued until his death. For over 25 years he was acknowledged as the “Grand Old Man” of Winnipeg’s musical world, with his distinguished deep voice and the image of a “long haired Oscar Wilde individual, dividing his time between musical scores and caustic criticisms of overblown musicians.” Wheeler saw himself as a trained cosmopolitan personality whose duty it was to bring decorum and dignity to the performing arts in Winnipeg. He was committed to improving the quality of vocalists and musicians in the city and criticized freely to that end.

On New Year’s Day 1917 Wheeler was on his way to the Walker Theatre when he fell on an icy sidewalk. He died a week later at age 78. His friend Archdeacon Octave Fortin of Holy Trinity Church remarked that Wheeler’s outstanding quality as an architect had been his “faithful inspection of his buildings” so that “no slovenly or unworthy work ever escaped his vigilance.” As a music critic, Wheeler had exhibited “good judgement and strict honesty.” Three sons carried on their father’s tradition – Alfred Harry was a choirmaster and architect in St Paul, Minn., Charles William was a musician and architect in Port Arthur (Thunder Bay, Ont.), and Arthur Wakefield practised as an architect in Edmonton and Winnipeg.

Charles Henry Wheeler was not an influential designer – he was a cosmopolitan Englishman who came to a prairie city and, because of his integrity, was a model to the citizens whose lives he touched.

Charles Henry Wheeler is the author of “Music and our musicians,” Winnipeg Tribune, 20 Dec. 1890; “The evolution of architecture in northwest Canada” and “Winnipeg,” Canadian Architect and Builder (Toronto), 10 (1897): 8 and 13 (1900): 130 respectively; and “Some personal theatrical and musical reminiscences,” Winnipeg Town Topics, 17 Dec. 1910–18 Jan. 1913.

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Geneal. Soc. (Salt Lake City, Utah), International geneal. index. City of Winnipeg, Arch. and records control branch, Assessment rolls; City Clerk’s dept., building permits, 1900–6. “Charles H. Wheeler: dean of musical and dramatic critics in Winnipeg and Canadian west,” Winnipeg Town Topics, 17 Dec. 1910. Winnipeg Tribune, 1 Aug. 1891, 13 Oct. 1896, 8 Jan. 1917. G. B. Brooks, Plain facts about the new city hall; its inside history from the first down to the present; interesting disclosures (Winnipeg, 1884). George Bryce, A history of Manitoba; its resources and people (Toronto and Montreal, 1906). Canadian Architect and Builder, 1 (1888)–22 (1908). Directory, Winnipeg, 1882–1917. Octave Fortin and C. [C.] Carruthers, Sixty years and after: an historical sketch of Holy Trinity parish, Winnipeg . . . also, an outline of present day activities and possible future developments (Winnipeg, 1928). Saturday Night, 20 Jan. 1917. Reg Skene, “C. P. Walker and the business of theatre: merchandizing entertainment in a continental context,” in The political economy of Manitoba, ed. James Silver and Jeremy Hull (Regina, 1990), 128–50. David Spector, “From frivolity to purposefulness: theatrical development in late nineteenth century Winnipeg,” Canadian Drama (Waterloo, Ont.), 4 (1978): 40–51.

Cite This Article

Giles Bugailiskis, “WHEELER, CHARLES HENRY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 27, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wheeler_charles_henry_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wheeler_charles_henry_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Giles Bugailiskis |

| Title of Article: | WHEELER, CHARLES HENRY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | April 27, 2025 |