Source: Link

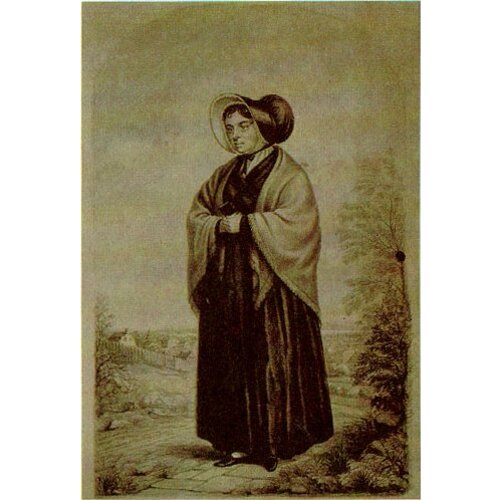

RUCKLE, BARBARA (Heck), b. 1734 in Ballingrane (Republic of Ireland), daughter of Bastian (Sebastian) Ruckle and Margaret Embury; m. 1760 Paul Heck in Ireland, and they had seven children, of whom four survived infancy; d. 17 Aug. 1804 in Augusta Township, Upper Canada.

Normally, the subject of a biography has been a major participant in significant events or has enunciated distinctive ideas or proposals, which have been recorded in documentary form. Barbara Heck, however, left no letters or statements; indeed the evidence for such matters as the date of her marriage is secondary. There are no surviving primary sources from which one can reconstruct her motives and her actions throughout most of her life. Nevertheless she has become an heroic figure in the early history of Methodism in North America. In this instance, the biographer’s task is to define and account for the myth and, if possible, to describe the real person enshrined in it.

The Methodist historian Abel Stevens wrote in 1866: “The progress of Methodism in the United States has now indisputably placed the humble name of Barbara Heck first on the list of women in the ecclesiastical history of the New World. . . . The magnitude of her record must chiefly consist of the ‘setting’ of her precious name, made from the history of the great cause with which her memory is forever identified, more than from the history of her own life.” Barbara Heck was involved fortuitously in the inception of Methodism in the United States and Canada, and her fame rests on the natural tendency of a highly successful movement or institution to glorify its beginnings in order to strengthen its sense of tradition and continuity with its past.

Barbara Ruckle was a member of a distinctive community of German refugees, commonly known as the Palatines, who were settled in Ireland by the British government in 1709. In the wake of John Wesley’s second visit to Ireland in 1748, which would lead to the establishment of the Irish Conference, many in this group of about 100 families became Methodists. Among the converts who were brought together in Methodist societies were Barbara Ruckle and her future husband, Paul Heck. In 1760, the year of their marriage, the Hecks, along with several other families of their faith, emigrated to New York intending to found a linen factory in New York City. This objective was not achieved and the new settlers took various other forms of employment.

At this time Methodism had not penetrated formally to the British North American colonies and without leadership the little group of German-Irish Methodists became religiously indifferent. The tradition, which is doubtless largely authentic, is that Barbara Heck’s concern about their worldliness came to a head in 1766 when she came upon a group of her friends playing cards in her kitchen. Angrily she “lifted a corner of her apron, swept the cards from the table into it with her hand, went to the fire and cast them from her apron into the flames. . . . She put on her bonnet and went to Philip Embury and said to him, ‘Philip you must preach to us or we shall all go to hell together, and God will require our blood at your hands!’” Embury, formerly a local preacher in Ireland, hesitantly took up her challenge and held the first service in his home. It was attended by five persons including the Hecks and their African slave. The congregation grew rapidly and in 1768 the Wesley Chapel (John Street Church), the first Methodist church in New York, was opened.

By the mid 1760s continuous emigration from Britain had brought many former Methodists to the North American colonies. The group gathered by Mrs Heck’s example was one of several which emerged in Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New York. Wesley’s awareness of this development led him to send two missionaries to New York in 1769. They and their successors, notably Francis Asbury, would lay the foundations of the Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States between 1784 and 1800. Meanwhile, through their own movements, the Hecks and other Palatine families participated unwittingly in the diffusion of Methodism.

In 1770, evidently dissatisfied with life in New York, a group including the Emburys and the Hecks settled in Camden Township near modern Bennington, Vt. Again Embury formed a society, at Ashgrove, N.Y., which subsequently became a major centre of Methodism in the New York Conference. The growth of the Camden community was interrupted, however, by the onset of the American Revolutionary War. Paul Heck enlisted in a loyalist regiment and inevitably, in 1778, his farm was confiscated by the rebels. The Hecks, offspring of refugees, now became refugees themselves, members of the motley collection of people who were caught between the bitter proponents of the imperial government and of colonial independence. As such, they sought refuge in Montreal, Que., and as loyalists were resettled in 1785 in Township No.7 (Augusta).

Paul and Barbara Heck and their surviving children established a new home on the third concession of Augusta. They and other former Palatine families who came to this area and to the Bay of Quinte townships apparently sought to keep alive the rudiments of Methodist fellowship and discipline. These two groups were the nuclei of the first circuits in what would become the Canada Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church. Paul Heck died in 1795; Barbara died suddenly on 17 Aug. 1804 in her son Samuel*’s home. She was buried in the cemetery of the Blue Church (Anglican), near modern Prescott.

In 1909 the Methodist churchman Albert Carman* commented that Barbara Heck “led a humble, holy, blameless life, and died among her kindred with her Bible . . . on her knees.” It is characteristic of the legendary quality of that life that the Bible she held was not in German, as tradition has it, but in the Netherlands language; and that the recently demolished Heck house which was claimed to be her home was not the one in which she spent her last years. There is no reason, however, to doubt Dr Carman’s assessment. Her determination surely had something to do with the growth of Methodism in New York City; similarly her faith must have influenced her family and her friends to remain loyal to Methodism in adversity and migration. Samuel Heck’s career as a prominent local preacher in the St Lawrence settlements was at least in part a testimony to his mother’s strong convictions. It is wrong, however, to assert as older Methodist writers have that Barbara Heck and the Palatine families played a decisive part in the foundation of Methodism in the British North American colonies. They were a minute group in an evangelical movement in the North Atlantic world which was fostered by a multitude of persons galvanized by the preaching of John Wesley, George Whitefield, Jonathan Edwards, and many lesser figures.

In retrospect, it is evident that the glorification of Barbara Heck reflected the pride of Canadian and American Methodists in the rapid growth of their denomination in the 19th century and their firm belief that history is the record of the work of Providence in time. Viewed from a longer and different perspective, the study of her life illuminates the ease with which history can become hagiography, and the persistent search in our society for meaningful personal links with the past.

[The accounts of Barbara Heck in the older secondary sources are essentially hagiographical. They do incorporate, however, letters and reminiscences by persons who knew her children, grandchildren, and other relatives. The information contained in these is consistent with the available documentary evidence, most of which concerns Mrs Heck’s relatives and friends. Paul Heck’s “German Bible,” actually a Dutch New Testament and Psalter, is at the United Church Arch., Central Arch. of the United Church of Canada, Toronto.

In From Wesley to Asbury, infra., Professor Baker has clarified the outlines of the first phase of Methodist history in the Thirteen Colonies. g.s.f.]

United Church Arch., Central Arch. of the United Church of Canada, “A collection of documents relating to the Hecks, Emburys, and other clans” (copies). Frank Baker, From Wesley to Asbury: studies in early American Methodism (Durham, N.C., 1976). J. [S.] Carroll, Case and his cotemporaries . . . (5v., Toronto, 1867–77). William Crook, Ireland and the centenary of American Methodism . . . (London, 1866). E. C. Lapp, To their heirs forever (Picton, Ont., 1970). Abel Stevens, The women of Methodism . . . (New York, 1866). W. H. Withrow, Barbara Heck: a tale of early Methodism (Toronto, 1895). J. W. Hamilton, “Address at the unveiling of the monument to Barbara Heck,” Christian Guardian (Toronto), 4 Aug. 1909: 23–26.

Cite This Article

G. S. French, “RUCKLE, BARBARA (Heck),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ruckle_barbara_5E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ruckle_barbara_5E.html |

| Author of Article: | G. S. French |

| Title of Article: | RUCKLE, BARBARA (Heck) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1983 |

| Year of revision: | 1983 |

| Access Date: | December 30, 2025 |