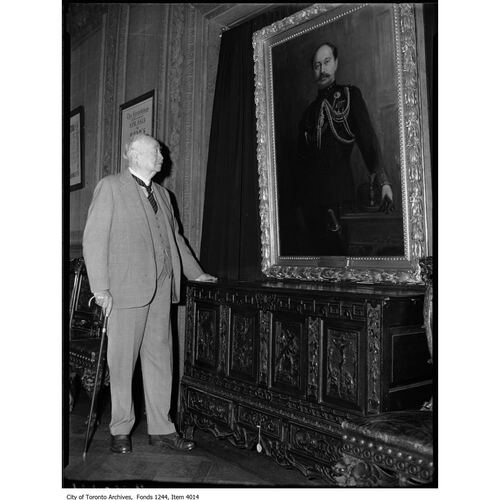

![Sir Henry Pellatt views his own portrait at Casa Loma. [ca. 1930]. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 4014, William James family fonds. Original title: Sir Henry Pellatt views his own portrait at Casa Loma. [ca. 1930]. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 4014, William James family fonds.](/bioimages/w600.11615.jpg)

Source: Link

PELLATT, Sir HENRY MILL, athlete, businessman, militia officer, and philanthropist; b. 6 Jan. 1859 in Kingston, Upper Canada, eldest son of Henry Pellatt and Emma Mary Holland; m. first 15 June 1882 Mary Dodgson (d. 15 April 1924) in Toronto, and they had a son; m. secondly 12 March 1927 Catharine Welland Merritt (d. 19 Dec. 1929) in St Catharines, Ont.; d. 8 March 1939 in Mimico (Toronto).

Henry Pellatt Sr had begun his career in London, England, with the Royal British Bank. In Kingston he clerked for the Bank of British North America in 1852 and then the Bank of Upper Canada. A side venture into mercantile trade ended in collapse and the family’s move to Toronto in 1859, when his eldest son was still an infant. Pellatt resumed work with the Bank of Upper Canada; after its failure in 1866, he made a fresh start as a notary, financial agent, and broker. The following year fellow bank employee Edmund Boyd Osler* became his partner. Riding the emerging shares market, they joined the Stock Exchange Association in 1871.

By this time the Pellatts had moved from Toronto’s Cabbagetown district to the more fashionable Sherbourne Street. Harry was raised with three sisters and two brothers; there was little in his boyhood to herald his future persona. He entered the Model Grammar School in 1868 and subsequently spent three months at Upper Canada College in 1876. His modest academic proficiency was surpassed by his athletic prowess. The trim youth excelled at track, especially the mile; his speed was honed after he joined the Toronto Lacrosse Club (TLC). Between 1875 and 1880 he swept meets in central Ontario. Hailed (and reviled) as one of Toronto’s “crack runners,” he won the dominion mile in 1878 and the American amateur mile the next year. He had become expert as well at shooting following his enlistment in 1876 in the 2nd Battalion of Rifles (Queen’s Own Rifles), commanded by TLC founder William Dillon Otter*. Pellatt saw his only active service when the unit was called out in January 1877 to quell a riot of striking railway workers at Belleville.

He had withdrawn from school to concentrate on his apprenticeship in his father’s firm, where he had been clerking part-time since he was 15. In 1881 he appeared as a scrutineer at the annual meeting of the Standard Bank of Canada. When Osler left the partnership the following year, Harry took his place in the brokerage, now called Pellatt and Pellatt, and became a member of the exchange. Though he had given up running, he participated in the annual stock-exchange games and would retain a lifelong interest in sport. For the 23-year-old, who had begun to enjoy travel to Europe, 1882 also marked his social arrival. In May he visited with Oscar Wilde after the Irish author’s Toronto lecture on aesthetics, a topic not lost on the young dandy. A few weeks later he married Mary Dodgson, a graduate of the elite Bishop Strachan School. They honeymooned in Europe and soon moved into their own residence on Sherbourne. From there Pellatt thrust himself further into society.

Given the smallness of the securities market, the Pellatt brokerage had also engaged in mortgages, loans, and insurance. The safest vehicles, it advised, were bank and loan-company stocks and government securities. Pellatt Sr, who was credited with producing the earliest financial reports in local newspapers, became president of the Toronto Stock Exchange (TSE) when it was incorporated in 1878. It was energized in the 1880s by a boom in bank and western land stocks. Other brokerages were opening, including that of Alfred Ernest Ames, as well as a key firm in the development of the bond market, George Albertus Cox*’s Central Canada Loan and Savings, where Harry would be appointed auditor in 1890.

Pellatt had quickly carved out a niche within the family business. He always held a chunk of his father’s cash for immediate investment. He was a good fit with the clubby milieu of the exchange, drew in militiamen who needed financial help, and attended to his own gain. With an abandon questioned by some financiers, he bought up as much stock as he could in Osler’s Canada North-West Land Company, which reputedly constituted the basis of Pellatt’s first fortune. In 1885–86, mostly on behalf of veterans of the North-West uprising [see Louis Riel*], the Pellatts handled substantial amounts of volunteer scrip for land. Henry Jr fixated as well on the emerging field of electricity. In 1883 John Joseph Wright* had founded the Toronto Electric Light Company (TEL), which supplied steam-generated energy. Pellatt joined as secretary; his low salary belied his grasp of the new technology. The city also awarded contracts for street lighting to Consumers’ Gas, but in 1889, while still obliged to tender, TEL secured rights to lay underground wires and operate appliances for 30 years, after which the city would take over its assets. In 1891, buoyed by its second five-year contract, the company issued its first dividend.

Pellatt’s wealth mounted in the 1890s, as depression gave way to boom. When his father retired in 1892, he took control of the brokerage and brought in Norman Macrae as a partner, but the firm did not absorb all of Pellatt’s time. In 1892 TEL had begun selling power for streetcars to William Mackenzie*’s Toronto Railway Company, which, significantly, in 1891 had obtained a 30-year franchise from the city. In 1895, by which date Pellatt had become president of TEL, it obtained another contract. The following year its absorption of Toronto Incandescent Electric Light brought into the fold the technical wizardry of Frederic Thomas Nicholls*.

Pellatt had also begun engaging in small-property development, while in the brokerage business he started to take subscriptions for shares in industrial companies. Banks and insurance firms, looking for new investments for their capital, found industrials, especially those with government franchises, attractive. Toronto’s money-men also scrambled to handle the unprecedented flood of equities from mining promotions in the Klondike and British Columbia. Brokers saw chances to invest funds, to form companies in order to create share issues, and to ally themselves with industrialists. Few worked these openings better than Pellatt, who “bloomed like a magnolia tree in the national garden,” one journalist commented. In 1899, when he bought into Cox’s western Crow’s Nest Pass Coal Company, he was well positioned to offer new industrials, among them the Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Company of Australasia and the Caribbean and South American utilities spearheaded by Mackenzie. Seen as a valuable addition to corporate boards, he became a director of Dominion Telegraph in 1895, of Toronto Railway, and of Canadian Lake and Ocean Navigation when it was founded in 1902, and he eased himself onto the boards of several more firms, among them Hamilton Electric Light and Power [see John Patterson*] and the Crow’s Nest Pass Railway [see John Duncan McArthur*]. In the bond and underwriting business, he invested heavily in Cox’s Dominion Securities Corporation, formed in 1901 on the initiative of Edward Rogers Wood*. That year Pellatt joined John Castell Hopkins*, who recognized his sway in the financial world, in launching the Canadian annual review of public affairs.

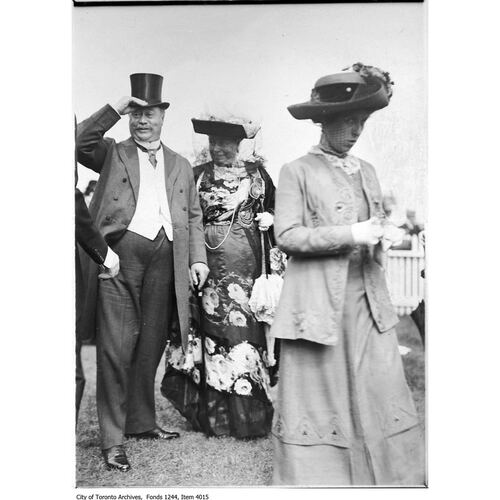

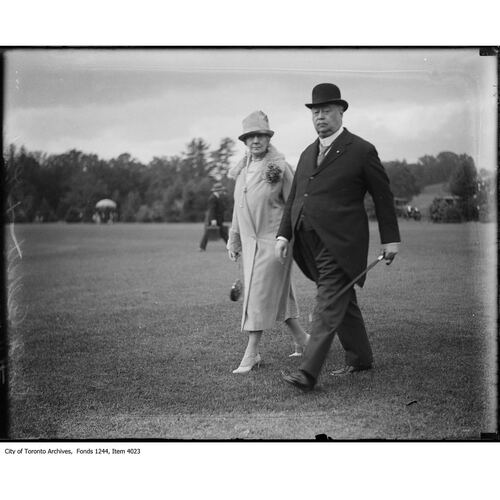

Pellatt’s rise in business sustained an escalating social prominence, some of it reflective of his family’s experience. His father, a club-man and Anglican with a summer home near Orillia, filled his Toronto house with art. Even if Emma Pellatt’s reported drinking problem created a rift with her eldest son, he was shaping up as a paterfamilias and would give his brothers jobs in his electric company. His landed assets included farms near Pickering and Port Credit (Mississauga) and, east of Toronto, a summer cottage that he named Cliffside, designed in 1891 by Langley and Burke [see Henry Langley*]. Pellatt’s ready mortgaging of properties such as these set one primary pattern for his generation of financial capital. Dilettantes both, he and Mary Pellatt began assembling their own art collection, which included Canadian works. They supported the Toronto Home for Incurables and the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), while Henry served as an honorary president of the Woodbine Cricket Club, commodore of the Royal Toronto Sailing Skiff Club, and a director of the Toronto Conservatory of Music [see Edward Fisher*]. A generous donor of awards – he presented a challenge trophy for drill to the Church Boys’ Brigade in 1896 – he played the part of benefactor. “Pellatt had an air of monied aloofness about him,” his biographer writes. “With hooded eyes that gave him a benign, sleepy appearance, an angular, well-trimmed moustache, and an insidiously receding hairline …, he was a compendium of characters that encompassed everything from kindly paternalism through to shrewdness and military severity.” Photographs reveal his increasing girth.

The press had already started to critique Pellatt or seek his views, as the Toronto Daily Star did in 1895 on civic government by commission and in 1901 on union with Newfoundland, but it was his military omnipresence that got the most attention. The Queen’s Own Rifles (QOR), a socially oriented cauldron of militia politics, was also an efficient unit. Pellatt trained assiduously; in 1889 he had formed a revolver association within the regiment. Promotions had come steadily – provisional lieutenant (1879), lieutenant (1880), captain (1883), brevet major (1893), major (1895) – and he served on the headquarters staff at the Niagara camp in 1898 and 1899. Behind the scenes, he was instrumental in efforts to oust his brother-in-law Robert Baldwin Hamilton, the QOR’s unpopular commander, who was succeeded in 1896 by Joseph Martin Delamere.

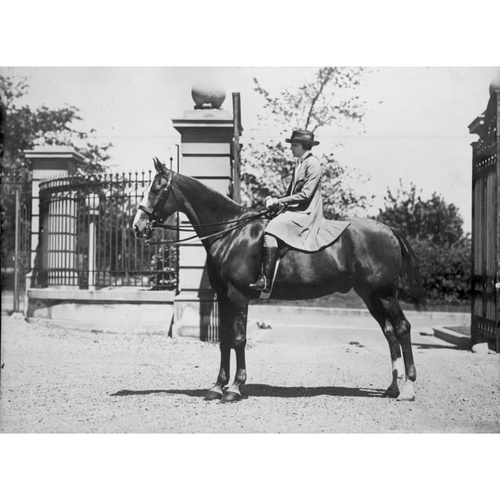

Family, holidays, and business drew Pellatt to Britain. The military further brought out his Anglophile tendencies. In 1897 he accompanied the Canadian contingent to the celebration of Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee and commanded the colonial guard of honour at St Paul’s Cathedral. He was upset that the troops received only a lukewarm reception. Two years later he paid to send his regiment’s bugle band to a tattoo in Montreal. However, when members of the QOR volunteered for the South African War, it was Frederick Mill Pellatt, not his brother, who stepped forward to serve, which he did for seven months in 1901–2. Henry remained in Toronto to tend to business and the political intricacies of the militia. His politics were pragmatically fluid. Favouring Sir Wilfrid Laurier*’s Liberals, then in power in Ottawa, he turned away a bid by Conservative heavyweights to get him to contest Toronto Centre in 1900. G. A. Cox, now a Liberal senator, had already laid out Pellatt’s military credentials in a letter to the influential minister of militia and defence, Frederick William Borden*. By early 1901 Pellatt had opened his own correspondence with Borden. In March that year he was appointed commanding officer of the QOR and promoted lieutenant-colonel. A devotee of pageantry, he was responsible for massing 11,000 soldiers on Toronto’s exhibition grounds in October for review by the Duke of Cornwall (the future George V), who rode Pellatt’s prized stallion.

The public knew nothing of Pellatt’s shameless manoeuvring a month earlier for grander cachet, nomination as the duke’s aide-de-camp. Though unsuccessful, he would be unrelenting in his pursuit of decoration and status. In 1902 he went to England in command of the contingent assembled to represent Canada at the coronation of Edward VII (its postponement until after Pellatt’s departure deeply disappointed him). Included was the QOR’s bugle band, whose expenses he covered; personal financing was meant to preclude charges of favouritism against the federal government. His command had been opposed by Governor General Lord Minto [Elliot*] and others who would have preferred a more experienced officer or South African veteran over a parvenu. They had reservations too over personal expenditures, but Borden prevailed. The controversy had been intensified by Pellatt’s brash campaign to form a second QOR battalion with himself as overall leader of the regiment. The move would be unprecedented, argued Richard Hebden O’Grady-Haly, the general officer commanding the Canadian militia from 1900 to 1902, but nonetheless in 1906 the expansion was approved and Pellatt became lieutenant-colonel commandant over the heads of 140 senior lieutenant-colonels. Elevation to colonel followed a year later. His climb had been consolidated in 1905 when he was made an honorary aide-de-camp to Governor General Lord Grey* and knighted. Nominally granted for his work in electricity, the knighthood was pure garnish. Rumours of his appointment as Ontario’s lieutenant governor ensued.

Without question, Pellatt’s connections and means enhanced his effectiveness as the QOR’s commanding officer, even though he saw soldiering as a means to social ascension. He understood the need to sustain the regiment’s size and popular image; enlistment hinged on them. When it came to labour disputes, he had witnessed the decline in volunteers that followed the posting of militia during a strike of streetcar employees in Toronto in 1902 and had cautioned Borden about this impact. But beyond the city the QOR was deployed to deal with unrest, as it was in a riot the following year at Sault Ste Marie, where Pellatt had invested in Francis Hector Clergue’s industries. The regiment’s dependence on his wealth was not unusual – other Toronto units (the 48th Highlanders, the Governor General’s Body Guard, and the Royal Grenadiers) also had rich, involved patrons – but Pellatt was lavish to a fault. He spent untold sums on training and uniforms, sent the regiment to shows, pushed for medals and promotions for personnel, staged socials, and resisted attempts to introduce temperance in barracks. “I am very anxious to keep the Corps up,” he told Borden in 1902 over the matter of getting a store of trousers, in order to prevent the loss of men to the Highlanders. In June 1910, to celebrate the QOR’s 50th anniversary, he backed a week-long celebration and historical pageant. In August, to continue the observance and demonstrate Canada’s assumed readiness for imperial engagement, he took the regiment to England, largely at his own expense, for a month of manoeuvres with Britain’s regular troops and territorials.

On larger militia matters, such as Borden’s drive for greater Canadian autonomy, Pellatt’s espousal of reform was muted. In their correspondence, amendments to the Militia Act in 1904 were rarely mentioned. As commander of the QOR, Pellatt had to show public support for Lord Dundonald [Cochrane], the general officer commanding, who opposed Borden’s changes. Like many other regiments, the QOR benefited from the minister’s move to create service corps within the militia; by February 1905 signals and machine-gun detachments had been added to the unit. Its complaints over the Ross rifle, introduced by Borden, fell to the side. In addresses on imperial mutuality, Pellatt, despite snubs in England, called for a strong Canadian militia capable of assisting Britain in wartime alongside its regular army. His pronouncements nevertheless lack intellectual depth, and he did not rise to the front ranks of imperialist spokesmen.

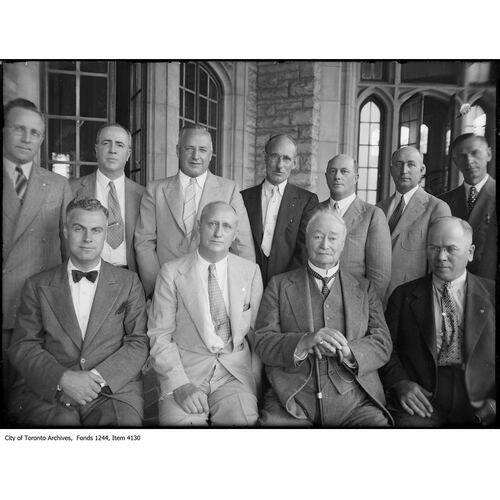

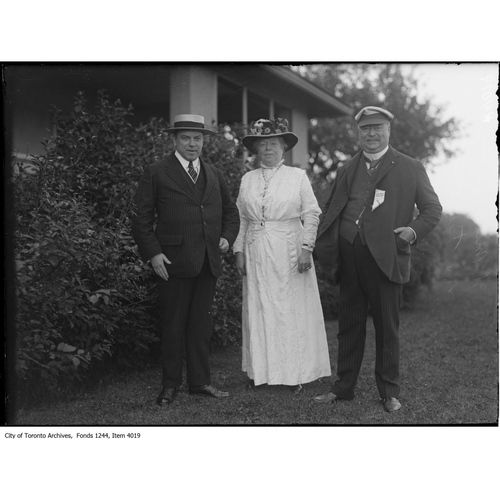

Concurrent with Pellatt’s military ascent in the years 1901–7 were his philanthropic endeavours and dizzying social life. Engagements at such venues as the Royal Canadian Yacht Club abounded, with ample opportunities to kowtow to worthy dignitaries. Extended trips were frequent. In September 1902, for instance, he left to shoot with a senator in Brandon, Man., meet with another (Cox) at Crowsnest Pass (Alta), and inspect oil lands in Colorado. He indulged his aesthetic passions (which some saw as ostentation) as a director and president in 1906 of the Toronto Guild of Civic Art, where, with others devoted to beautiful surroundings, he sat on the city-plan committee. Money provided entrées, and conspicuous spenders such as Pellatt expected recognition for their gifts. Boards embraced him, among them that of the Women’s Welcome Hostel, and in 1903 he financed a wing for Grace Hospital, where Lord and Lady Minto [Grey] unveiled his portrait.

On the strength of his donations, he had been appointed in 1900 to the endowment and finances board of Trinity College as well as to its council. He served as the board’s treasurer, a job he did well. In 1901 Pellatt suggested a conference on education, but federation with the University of Toronto was a priority, and Trinity provost Thomas Clark Street Macklem gently pushed the idea aside. Pellatt subsequently was a member of the federation committee. In 1910, on the eve of his military trip to England, Macklem proposed that Oxford be approached to give him a degree: “Sir Henry is not an academic man himself; but he thoroughly appreciates all that University means.” After the trip, citing his excellence as an “empire-binder,” friends advocated his elevation to the peerage as “Lord Toronto.” Pellatt remained content with recognition in London by various clubs and the Society of Knights Bachelor, to which he pledged £500 a year. So enamoured was he of things British that during his time in London in 1910 he bought Clifford’s Inn, the famous chancery building; that year he was also made a cvo. At home in Toronto, the country’s most imperialistic city, he belonged to the Canadian Defence League, founded in 1909 by, among others, William Hamilton Merritt*, whom Pellatt had known since their soldiering days in the 1880s.

Between 1907 and 1913, with more than 21 directorships, Pellatt was seen in print and in parliament as one of 23 capitalists anchoring Canada’s economy. Sketches by Alexander Fraser in his two-volume A history of Ontario: its resources and development (Toronto and Montreal, 1907) and Newton McFaul MacTavish* in the Canadian Magazine in 1912 signalled Pellatt’s standing, with few references to his ongoing business battles. At times a maverick, he prided himself on his access to the “inside Crowd” and cultivated the role of a broker to whom “one sort of commodity is about as interesting as another.” In an acknowledgement of Pellatt’s métier, F. H. Clergue offered him $100,000 in stock in 1911 to take over the presidency of a proposed engineering firm. Though Pellatt could harbour intense dislikes, he was valued for his calmness amid turbulence, as in the slumps of 1903 and 1907, but events could outstrip his talents. His failed attempt in 1907 to settle the running conflict between Dominion Coal (in which he held shares) and Dominion Iron and Steel in Nova Scotia was reportedly a factor in his resignation from the latter’s board [see James Ross*]. He was accused of colluding to sustain stock prices, an action he himself viewed as a bid to fend off stock raiders. His risk and engagement were spread across various fields throughout North America: insurance and banks, automobiles and shipbuilding, steel, railways, utilities and telegraphy, land development, natural resources, and publishing. His reach was measured too by his role as an incorporator of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway in 1903 [see Charles Melville Hays*], though his speculations were not above such minor ventures as a company set up to push a new rifle-sight.

Pellatt’s brokerage constituted a base, as well, for the expansion of Mackenzie’s South American enterprises in 1912–13. With knowledge of transoceanic telegraphy gained through his voyages to Britain and his involvement with New Yorker Clarence Hungerford Mackay, Pellatt chaired Northern Commercial Telegraph. He and his associates there shared an interest in early wireless, a field where stock shenanigans were slammed by American muckrakers. Pellatt shuttled between Montreal, Ottawa, London, New York, and the southern states, often to meet with bona fide magnates. In 1906, when Crow’s Nest Pass Coal was being recapitalized, he represented the company in consultations with the James Jerome Hill* group. He was not a known player in grand consolidations in the style of William Maxwell Aitken*, but he did launch some modest combinations. In 1910 he attempted with others to take over railways in the northeastern United States and brought Canada’s four radiator companies together to form Steel and Radiation. The following year, with QOR protégé Arthur Godfrey Peuchen*, he organized Standard Chemical, Iron and Lumber. Pellatt’s flirtation with British armament makers partly explains his interest in steel and shipbuilding in Nova Scotia. In 1911, with a British group, he bid to open a shipyard at Sydney, but despite a large municipal bonus, failure to secure naval contracts doomed the undertaking.

In broking Pellatt faced stiff competition, especially from blue-chip securities firms whose principals stuck to their business. In January 1907 his much-indulged son, Reginald, had become a partner in Pellatt and Pellatt. The size of its clientele is unknown, but its customers included former cabinet minister Sir Adolphe-Philippe Caron*, W. D. Otter, and Frederick Borden. Some authorities felt Sir Henry’s investments for clients were sounder than his own; Otter’s worth rose from $852 in 1909 to $41,592 in 1911. Pellatt also acted for his family. After the deaths of his mother in 1901 and his father eight years later, he took over their financial estates on behalf of his siblings, a duty complicated by difficult brothers-in-law. Mary Kate Hamilton had separated from her husband about 1904 (though they would appear together socially), and Emily Montford Rogers’s husband wanted money for his store.

During his rise to prominence, Pellatt drew censorious attention from the establishment, journalists, and in 1906 the federal royal commission investigating the life-insurance industry. He had been a key figure in two Toronto companies: a director (1899) and vice-president (1901) of Temperance and General Life and first vice-president (1902) of Manufacturers Life, which had been taken over by a Mackenzie-led syndicate that included Pellatt and had subsequently absorbed Temperance and General. As chair of the finance committee of Manufacturers, he had moved, often without authorization, to invest the company’s reserves in firms in which he had interests. He had also borrowed from the firm to cover a personal loss, providing securities and mortgages as guarantees. Company manager James Frederick Junkin, who saw nothing wrong, testified before the commission that Pellatt was considered a “good authority” on potential investments. Pellatt had borrowed too from Confederation Life, whose managing director disclosed other transactions made through Pellatt’s brokerage. Unmoved by theoretical standards of fiduciary principle, he never testified – he was in Britain on business – and on his return he declined comment, but the commission’s report of 1907 chastised him for his conflict of interest in Manufacturers Life, which it categorized as barely legal. Ontario premier James Pliny Whitney* privately regarded Pellatt’s modi operandi as “queer.” Harsher conclusions were drawn by William Findlay Maclean*’s World. On the other hand, this socially sanctioned process of funding ventures and creating demand for related securities was hardly aberrant. In a market with minimal regulation, differentiating between legitimate and unlawful speculations was difficult.

In 1906–7 Pellatt was preoccupied with more substantial matters, notably the enormous hydro potential of Niagara Falls and the high-stakes contest for control of electricity in Toronto. The provincial Liberal government of George William Ross*, which supported private development, had previously granted generating franchises to two American groups, with room for a third. Pellatt entered the picture to secure power for Toronto Electric Light. Early in 1902 parliament incorporated the Mackenzie group’s transmission company, Toronto and Niagara Power, with Pellatt as president. He played all the angles: he told Laurier he wanted to resist American capitalists, had one eye on the Hamilton market, and wished to bring in Borden as a director to link him with Mackenzie and “the rest of the financial men.” By November Pellatt, Mackenzie, and Nicholls had formed a parent syndicate, the Electrical Development Company of Ontario (EDC). The agreement with the province was signed on 29 Jan. 1903, and EDC was incorporated in February.

While Mackenzie was busy with his national railway enterprise, Pellatt’s work was crucial. After he had marshalled subscriptions and underwriting, control of EDC was transferred to Toronto Railway. The franchise rights were vested in EDC on 21 March, at which time Pellatt became president and Nicholls manager. Through stock manipulation Pellatt built up its worth, though it would remain constrained by a tight capital market. To handle excavation for the generating system at Niagara, begun in 1904, they had hired hydraulics expert Frederick Stark Pearson*. Construction of the ornate power station, designed in 1903–4 by Edward James Lennox, started in May 1906. Power began flowing in November, and TEL gradually shifted from steam production. Financiers in England were reluctant to take on EDC bonds, but through Borden’s introduction, Pellatt had persuaded the firm of Arthur Morton Grenfell to invest. Under Pellatt, administration was cliquish: in 1905 his broking partner’s brother, Hubert Hamilton Macrae, became manager and secretary of EDC and Toronto and Niagara Power.

Tarnished by public animosity against TEL and Toronto Railway, both of which had records of accidents and disruptions, EDC was treated with suspicion by the press and the city. “The Toronto papers have all been hammering us pretty bad re the Power Company,” Pellatt confessed to Borden in January 1903. “The public seem to think that the cities and towns ought to have built this … Company instead of private individuals, which of course is absolutely ridiculous and to commence with impossible.” The Evening Telegram, in particular, had been pecking at him since his coronation junket. Limited in his ability to deal effectively with his critics in a hotbed of civic populism, Pellatt nonetheless remained upbeat. At the cornerstone ceremony for the generating station, and elsewhere, “the great captains of industry” were praised by some for their risk taking, but support for the utility adventurers was cool.

The election of the Conservatives under Whitney in 1905 brought the issue of publicly owned hydroelectricity to the fore. Adam Beck*, the ideologically driven chairman of the Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario, which was created the following year, aggressively challenged the financially vulnerable EDC. Reluctant to see it collapse, Whitney, with whom Pellatt still socialized, wanted some accommodation, but Beck was ruthless. In January 1907 Toronto ratepayers authorized a by-law for a contract between the city and Ontario Hydro. In the subsequent fight over a second proposed by-law, which would fund a local electrical infrastructure, Beck gained from EDC’s weak base in the business community and Pellatt’s inability to muscle his way into the political arena. When necessary, Whitney blocked him with ease. Along with Wright and Nicholls, Pellatt spoke out against the by-law and the “cult” of public ownership; his proposal in the fall of 1907 that the city either buy TEL or place nominees on its board came too late. In January 1908 the by-law passed. The city set up an electrical department, and in the June provincial election Whitney’s hydro policy was endorsed. The by-law, the premier concluded, terminated any chances for Pellatt and his associates.

In subsequent attempts to buttress EDC, a stressed Pellatt was not a prime player. Mackenzie’s formation of a holding entity, Toronto Power, gave EDC new guarantees, but his offer to build a distribution system under government regulation could not slow Ontario Hydro. A vice-president of Toronto Power, Pellatt defended the consolidation on the grounds that the public-power lobby’s harassment had hurt EDC’s search for capital. Over the course of the contest, cartoonists, notably Samuel Hunter of the World, lampooned Pellatt, whose controversial promotion to colonel did not help. In the spring of 1908 the Globe refused to give his cause any space. The Mackenzie group hit back by trying to stir up investors’ fears and seeking disallowance of Hydro legislation through the federal government. Pellatt and H. H. Macrae’s brash attempts in Britain in 1908–9 to exert influence only alienated capitalists and produced further ridicule at home. The Toronto Hydro-Electric System, so named in 1909, began operations two years later.

During the fight Pellatt remained busily engaged as president of an emasculated TEL, which gave up its street lights and poles. In negotiations with the city it was Mackenzie who took the hard line, not Pellatt, who (writing from England in 1910) pleaded with Whitney for help. To consolidate his utilities, Mackenzie bought TEL (his “best customer”) in 1911 and concluded further reconstruction to produce a group strong enough to continue alongside Toronto Hydro. Pellatt’s proposal to Mackenzie to unite TEL and EDC as “one concern” fell on deaf ears. How Pellatt felt about such relegation is uncertain. From the sidelines he unwisely believed that TEL was solid until its contract expired in 1919 and that the alignment of TEL and EDC with Toronto Power would be good for their securities, which would in fact dive during the financial crisis of 1913. As late as April 1914 Pellatt and Wood were planning to exchange an issue of Toronto Power bonds for EDC stock (in order to reduce debt) but only, Pellatt explained, “if we can get Mackenzie to sanction this.”

Pellatt’s capacity to manage multitudinous interests was astounding. In 1906, as the insurance commission and the electrical gambit were unfolding, his attention had also been grabbed by the silver-mining boom in the Long (Cobalt) Lake region to the north. The plethora of claims, companies, frauds, and stockjobbing all made for an exciting but volatile market in Toronto. Given his inside knowledge and experience with mines in Colorado, British Columbia, and the Lake of the Woods area in Ontario, the lure for Pellatt was irresistible. Despite their sparring over hydroelectricity, the Whitney government gave him a way in, at a price. In August 1905 it withdrew two lake beds and a timber limit from exploration and claim. On 22 Nov. 1906 the Cobalt bed was put up for sale. An Ottawa-led syndicate combined with a Toronto group that included Pellatt, and their astounding bid, $1,085,000, was accepted the next month.

Almost immediately the Cobalt Lake Mining Company was formed, with Pellatt as president. It began shipping ore in January 1908. Though far from being the area’s richest mine, the operation brought him great wealth. At the end of 1912, over shareholder objections, he brokered its acquisition by a London syndicate, a deal that included the sale of his one million shares. Silence about the mine’s luck was vital. “I want it kept as private as possible,” he had written to Frederick Borden in July 1911, “for the ultimate success is in keeping the stock down as such a large amount has to be bought for cancellation and if the stock was to go up, it would be impossible to carry out our scheme.” Opponents also challenged, without success, the allocation of 380,000 shares as “promotional stock” and 100,000 shares to Pellatt for his brokerage expenses. Likely with the syndicate’s imprimatur, he returned in 1914 as president of the Mining Corporation of Canada, with which he would remain involved into the 1920s. By 1917 his interest had extended to the Porcupine goldfield [see Benjamin Hollinger*]. His northern engagement was extensive: a president, director, and troubleshooter with various companies, he acquired options, arranged syndicates, grubstaked prospectors, and maintained a private lodge.

Most challenging for Pellatt in the long run was property development in Toronto. Between 1911 and 1914 he had acted through yet another British syndicate to purchase large tracts. In 1911 he sold land on Bay Street to the TSE for permanent quarters. As president of Arena Gardens of Toronto, the one-time athlete promoted the construction of an artificial-ice rink on Mutual Street. Opened in May 1912 under the management of Lawrence Solman, it was home the following winter to two professional teams in the National Hockey Association of Canada. In 1912–13 Pellatt launched three subdivisions on the outskirts of the city – Glen Grove Park, Cedar Vale, and Pelmo Park – all ambitious in scale. In Cedar Vale, which was handled by one of his three realty firms, British and Colonial Land and Securities, the surviving Connaught Gates near Bathurst Street attest to the grandeur planned. In 1913 he was involved with a holding company, Toronto Properties, in finding the money for a big hotel project that fell through. Less expansive was his likely role in the group that bought into Forest Lawn Mausoleum in York Mills (Toronto) in 1913.

Much of Pellatt’s suburban work was delayed by the Great War, a situation that forced him to carry the financing for longer than he had expected. Equally problematic was the hostility of city officials and the press, especially the World, which was disgusted by the arrogance of such “land butchers.” Among the financial establishments, the Bank of Montreal kept its distance. It was the small, Toronto-based Home Bank of Canada that played close. Run by James Mason and from 1916 by his son, Pellatt’s military associate James Cooper Mason, it had long been converting deposits into loans and funding the Pellatt brokerage. In 1912 a profit of $889,000 was generated by Pellatt’s purchase for development of farmland north of property he had acquired for his own use and the farmland’s sale to his Home City Estates, a gain achieved through stock-watering and loans from the bank, with no certainty of repayment. Favour begat favour; in December that year a Pellatt syndicate acquired shares in the troubled Banque Internationale du Canada [see Sir Rodolphe Forget*], facilitating its takeover by the Home Bank.

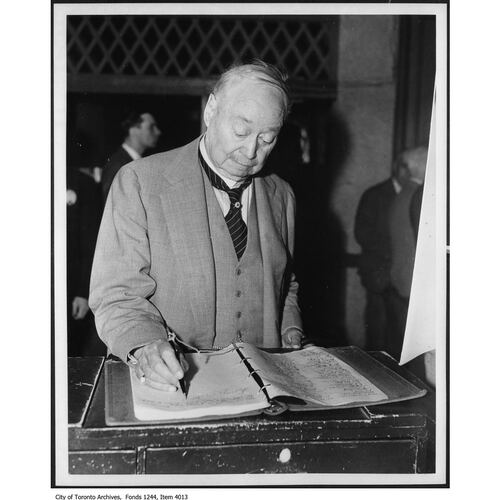

In late 1913, in the midst of development work, the Pellatts moved into their own grandiose but unfinished mansion looking south over the city. In 1903–5, in his wife’s name, Henry had bought lots on the escarpment, already called Casa Loma, near the stately houses of music dealer Samuel Nordheimer and entrepreneur Albert William Austin. His interest in residential glory befitting his self-perceived status was no secret. The name Casa Loma, meaning house (on a) hill, had romantic connotations in art and literature, and Pellatt relished the imagery. The building was his greatest architectural initiative. He would later explain his goals in different, sometimes unlikely, ways. A habitation, a soldiers’ hospital, and a military museum and library emerged often; to one journalist he confessed, “I intended it for a spectacle.” Its creation, he boasted, “gave vent … to an architectural flair which I exercised, in study and observation, all over the world.” To design the complex Pellatt chose his favourite architect and Sherbourne Street neighbour, E. J. Lennox, rather than a cutting-edge designer, and good ones were available in both Toronto and Montreal. Lennox indulged Pellatt’s liking for castles, grand hunting lodges, and mansions in Europe, and he was given a bottomless budget. Construction began in 1905 on a temporary cottage dwelling and a massive stable; in late 1909 work started on the main building, formed of grey-brown sandstone with white, cast-stone trim and red tile roofs. Its irregular plan contains a square north tower above a massive porte-cochère, a round western tower of five storeys, and a dramatic eastern tower. Between them are crenellations and lofty chimneys. Within are nearly 100 rooms, including a library for 10,000 books, and state-of-the-art electrical systems.

Lennox’s designs were executed in a medley of Edwardian revivalist styles. Though Casa Loma displays craftsmanship of a high order, the architectural result is derivative and undisciplined, major changes having occurred during construction. Lacking stylistic innovation, outdated even, the project was not Lennox at his best. Architectural journals and critics largely ignored it, while public reaction was mixed. Some found it to be the epitome of distasteful display, reflective of Pellatt’s absurd side; others lauded its bold projection on Toronto’s skyline; one newspaper would dub it a “Canadian Baronial Castle.” Close in spirit to the smaller but still garish mansions of American magnates in the Thousand Islands, Casa Loma was the largest private residence ever built in Canada, instantly a major landmark and a monument to unrestrained capitalism. Upon hearing of Pellatt’s plans in 1905, the Brantford Expositor had concluded, “Manifestly social conditions are changing in Canada and the plutocrat is with us at last.” Looking about Toronto society in 1911, Colonel George Taylor Denison* maintained, “Parvenus are as plentiful as blackberries and the vulgar ostentation of the common rich is not a pleasant sight.” A year later Sir William Bull, a visiting mp from Britain and registrar of the Society of Knights Bachelor, of which Pellatt was knight principal (president), likened Casa Loma to the “most beautiful palace of the best princess” in the “most expensive illustrated fairy tale” from London’s premier bookstore. He was equally dumbfounded by the model farm and summer retreat that Pellatt had begun to create in 1911 north of Toronto at Bales Lake, which he renamed Lake Marie after his wife (it would eventually be called Mary Lake). “If I were rich I do not think I should be so eager to show all my possessions to my friends,” Bull wrote, though publicly he would call Pellatt “the Cecil Rhodes of Canada.”

Casa Loma cost Pellatt millions – estimates range up to three and a half million dollars. It was an enormous responsibility, its relationship to the city rough. Starting in 1903, he had tackled both Toronto and York Township for land, road allowances, and service concessions. The animosity of councillors and departmental staff would be intensified by the hydroelectricity disputes. The recession of 1913 contributed to Casa Loma’s unfinished state, and the city’s abolition of fixed assessment that year boosted Pellatt’s taxes sixfold. Nonetheless, the potential for display was tremendous. The Pellatts brought their collections with them and added a profusion of imported antiques and reproductions. The library, however, would never be filled. In 1912 Sir Henry had struck an agreement to acquire old arms and armour for himself and the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) through its curator, Charles Trick Currelly*.

The mansion gave the couple a splendid stage for their social and philanthropic endeavours. A patron and member of local chapters of the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire (IODE), Lady Pellatt was named the first chief commissioner of Canada’s Girl Guides in July 1912. Seemingly reserved, she believed she had “sufficient influence” for this imperial-minded task, not to mention the finances to open the Guides’ initial headquarters in December. As well, she had the support of her husband (a donor to the more martial Boy Scout movement) and the wives of his associates, among them Rosaline Rebecca Torrington from the Toronto College of Music [see Frederick Herbert Torrington*]. Sir Henry’s interests were widespread: imperial organizations (he was a life member of the Empire Club of Canada and had “Imperial” added to the name of the Society of Knights Bachelor), coronation medallions for schoolchildren, and a stream of nobles and other visiting dignitaries. In 1911 he established a Canadian district of the St John Ambulance Brigade Overseas and became dominion deputy commissioner. The following year he supplied the first uniforms for St John’s personnel in Canada, was made a knight of grace by the Order of St John of Jerusalem in England, and received an honorary dcl from King’s College in Nova Scotia, where in 1914 he would endow a chair in philosophy. A knowledgeable equestrian and showman, he was consulted for Reginald Symons Timmis’s Modern horse management (London and Toronto, 1914). Some of his commitments would stop in bad times, as was the case with his pledges to the ROM.

Always, there was the military. In February 1912 Pellatt had relinquished command of the QOR, though his tenure was extended to April. In February he was also made commandant of the 6th (Toronto) Infantry Brigade (with the continuing rank of colonel) and in June honorary lieutenant-colonel of the 2nd Battalion, QOR. He participated in militia exercises at Niagara that on 12 November reportedly involved an early use of wireless in Canada, reflective of his commercial interests and experience with military radio in England in 1910. As well, he was a president of the Canadian Infantry Association and a member of the Canadian Military Institute. His politics remained fluid. He had supported the Liberals’ push for reciprocity in 1911, but when they lost power to the Conservatives under Robert Laird Borden that year, he backed the selection of his old friend Samuel Hughes* as minister of militia and defence. In 1912 Pellatt was placed on the department’s committee on railways. Not the least of his concerns were his fanatical pursuit of his own Coronation Medal, which he eventually received in 1913 through rare royal intervention, and his plans to fund a new armoury for the QOR, which never materialized. Rumours had him in line for high commissioner in London, foreign papers lavished praise, and the mayor of Sydney, desperately wanting Pellatt’s shipyard, dubbed him the “uncrowned king of Canada.” Likening him to the grandeur-deluded money-grubbers in Arcadian adventures with the idle rich (New York and Toronto, 1914), a collection of satirical sketches by Stephen Butler Leacock*, his sister Mary’s son-in-law, is not far-fetched. Leacock was certainly familiar with social theories on esteem acquired by displays of wealth. Then as now, in a template that fits Pellatt, the primary motivations for aggressive ostentation are status and prestige.

At the beginning of 1914, with Canada moving away from recession but with war looming, his outlook was positive. Like many others, he anticipated a struggle of short duration. For years he had been gratuitously pitching the dominion’s place in any imperial conflict. He even leaked letters seeking his opinion on the readiness of Canadians to serve. The war had a dramatic impact on business, but Pellatt was adaptive. He had been routinely attending to a range of interests, among them a never-ending run of stock offerings that included United Motion Picture Theatres in January 1914. By early the next year his Steel and Radiation company in Toronto had secured shell contracts that would test his political savvy. Conscious of claims in the press that Pellatt had reported “inordinate” profits, the chair of the Shell Committee [see Hughes], under prodding from the prime minister, had him issue a refutation in December 1915. The next year Conservative mp Frank Stewart Scott caused a stir when he described Pellatt as a “self-advertiser” who at war’s end would dump Steel and Radiation stock on an “unsuspecting public.” Pellatt ignored such slurs, though he did challenge some in court. The plant of another of his wartime promotions, Curtiss Aeroplanes and Motors, was sold to the Imperial Munitions Board at a substantial profit in 1917 [see Sir Frank Wilton Baillie*]. That same year, moving on a project deferred from 1914, he brought together three companies to form Security Life Insurance.

The sacrifices of war made Pellatt’s excessive style look anachronistic, even as his quest for honorifics went unabated. In 1915 he had pestered Hughes and others to help secure his promotion to brigadier-general, a rank he would receive on a temporary basis in July 1916. Named a Toronto member of the federal Military Hospitals Commission (MHC) in June 1915, he was formally the local chair and he understood the need to care for veterans, but the driving force was businessman William Kerr George. The commission’s meeting in December at Pellatt’s office was followed by a dinner and concert at Casa Loma. When such extravagance failed to bring him the standing he expected, he dropped out of active involvement, though in 1918 he would be named to the MHC’s successor, the Invalided Soldiers’ Commission. In 1915 he also accepted W. H. Merritt’s invitation to become a trustee of the Canadian Aviation Fund. Between June 1917 and the war’s end, in addition to his brigade duties, Pellatt held temporary command of the QOR. He and his wife appeared regularly in support of the troops, as patrons, through the IODE, St John Ambulance, the Canadian Red Cross Society, and patriotic and fund-raising committees, and as hosts at Casa Loma of such luminaries as the Duke of Devonshire [Cavendish], the governor general. Lady Pellatt directed the move to have the Canadian Council of the Girl Guides Association federally incorporated in 1917, four years before she retired as commissioner because of illness, but not all viewed the organization with fervour. In 1915 Protestant churches and the YWCA had founded Canadian Girls in Training in a show of dissatisfaction over the Guides’ secularism, failure to involve girls in decision making, and imperialist intent.

Pellatt’s decline was stark. Scott had not been the only one to prick his image in 1916. Journalist Augustus John Bridle*, who knew the broker from such mutual interests as the National Chorus [see Albert Ham], gave a mean sketch of him in Sons of Canada: short studies of characteristic Canadians (Toronto, 1916). He ridiculed Pellatt’s “plethoric and pompous figure” on parade and his penchant for self-promotion, a hustler spewed out by boom times. “Any good standard recipe for building a new nation might safely include one Pellatt. More would be dangerous.” Like his life in finance, Pellatt’s military career ceased when he was in his sixties: in 1920 he was transferred from brigade command to the reserve, and the next year he received his final promotion, to major-general. In the pecuniary sphere, loans from Mackenzie were outstanding, and his debt to the Home Bank from at least 1911 had been mounting, an account worsened by his risky real-estate ventures and the shift in his loan securities to industrials in which he had interests. The bank was reluctant, during a wartime economy, to close in on Pellatt, a man of presumed stature. Some officials thought he would pay off his debts, but as early as 1915 three western directors were sounding alarms over the bank’s weak state, particularly three major accounts. Pellatt’s obligation stood at $2,191,732.81 on 30 November that year. Elgin Development Land Securities, which he formed in 1916, allowed for some restructuring; it was this company that would take over his office building in 1923 and other of his properties.

At the end of the war a circumspect E. R. Wood attempted without success to get him to clean up his accounts before the economy slumped. Pellatt and Pellatt had been surpassed by other securities houses, A. E. Ames’s being one, and though it continued to operate – it even had its own real-estate department – Sir Henry was winding down. He looked shaky. Feuds opened up in his mining companies and American oil projects failed. In 1920, in the midst of the troubled British Empire Steel merger [see George Henry Murray*], he gained a place on the new board of Dominion Iron and Steel, only to see the enterprise flounder. His presidency of Toronto Electric Light had ended unceremoniously in 1919. With the electric and street-railway franchises expiring, bitter negotiations were followed in 1922 by the takeover of the Mackenzie group’s interests in the Toronto region. A gutsy spokesman to the end, Pellatt was chastised in the press. William Henry Pope Jarvis, who had gone after Pellatt’s Cobalt manipulations, revived his attack in 1920, while in Maclean’s and the Financial Post Joseph Lister Rutledge tracked the broker’s “careless optimism.” “He isn’t a financial genius and never was,” Rutledge wrote, though, confronted by Pellatt’s opaque front, “one questions if anything in the way of an accurate estimate of him could be made.”

Between 1919 and 1921 Home Bank officials rebuked him for deceiving them on land deals and for skimming funds, but they could not let him off the hook. As he brazenly explained, he had borrowed from nine institutions, and removing him from his maze of debts and holdings would have dire consequences. Though he had reported income of $66,006 in 1920, not all bankers saw him in the same light. He was regarded at the Dominion Bank “as a man of means,” but Herbert Deschamps Burns of the Bank of Nova Scotia claimed that “he is always hard up.” In 1923 Pellatt established the first of two holding companies to give the Home Bank control of his assets while releasing him from further liability. However, late that year, during the fallout from the bank’s failure in August, the Pellatts had to move from Casa Loma to an apartment. The inquiry into the bank’s demise opened on 16 April 1924, the day after Lady Pellatt died. Pellatt did not testify, but his account and properties were publicly dissected. In June the contents of Casa Loma, technically his wife’s estate, began to be sold at auction.

Pellatt still garnered attention, including an audience with the Prince of Wales in 1924 and a massive gathering at Lake Marie in 1926 to honour his half-century with the QOR. The following year he lent his name to the formation of the North American Relations Foundation. Other bright spots were his marriage in 1927 to W. H. Merritt’s sister, a veteran of the IODE who had known him since she was 12, his receipt of the Colonial Auxiliary Forces Long Service Medal two years later and accolades from the Canadian Military Institute, and his election as president of the St George’s Society in 1930. He had retired from his brokerage in 1925, leaving it to his son, but he kept up some involvement in business. His peddling of shares in a land speculation near Detroit, Mich., was pathetic. His operation of Dominion Telegraph Securities, set up in 1925 to manage capital, later produced tax problems. Through a new syndicate Pellatt revived work on the Cedar Vale subdivision. In 1927 he possessed shares in 56 companies, including interests in brewing and industrial alcohol, and still held the presidencies of a few mines and Dominion Sewer Pipe and Clay Industries, which he led into a merger, only to see it run afoul of infighting. At most turns his money was controlled by the trustee appointed in the liquidation of the Home Bank. Funds that did come his way were put into new schemes or spent, and he mismanaged the assets from his parents’ estates. Leacock had justified fears that Pellatt was draining off Mary Hamilton’s share. Plans to convert Casa Loma into apartments and a hotel, sometimes with Pellatt’s involvement, were overwhelmed by difficulties. To recoup taxes, the city took over the property in 1933 and considered forcing him into bankruptcy. It must have been hard too for him to give up Lake Marie, the core of which was sold in 1935, during the Great Depression, to the Marylake Agricultural School and Farm Settlement Association, a Roman Catholic organization.

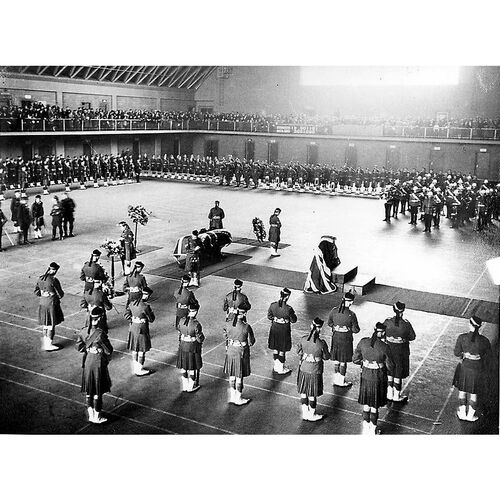

The contrast between Pellatt’s poverty and his continuing social artifice was sad, a state compounded by his failing sight – by August 1932 he could not read. He was forced to move to other apartments and, finally, a room at his former chauffeur’s home in Mimico. During a poignant interview in January 1930 he had professed, “I don’t look back much,” though he did – to his racing days, the QOR, and the excitement of building Casa Loma. At a luncheon in 1937 he tendered a defiant but erroneous take on his former home. His sale of adjoining land, he claimed, meant that the mansion had not cost him a cent. Because he intended it to be a museum, it had been exempt from taxation, but when the city started assessing the property, he walked away, saying, “Gentlemen, you can have it.” Pellatt’s last public appearance occurred in January 1939. A “shambles” of a man, he died two months later and was given a military funeral at St James’ Cathedral, followed by interment at Forest Lawn beside his first wife. Some obituaries touched on his financial carelessness. Reg Pellatt, whose relations with his father had reputedly endured tensions, faced an empty estate. Pellatt’s few effects included his cherished racing trophies.

Accounts of Sir Henry Pellatt range from oft-repeated hagiography to disparagement. Personal documents are sparse; anecdotes abound. Apart from his blatant need for recognition, his motivation remains obscure. In the resulting vacuum, and with Casa Loma as the overwhelming measure, depictions of the man as absurd and buffoonish are not easily countered, especially since they hold some truth. Carlie Oreskovich’s biography utilizes new sources, with sympathetic results but contextual limitations. Newspapers of the period reveal significant patterns in his swaggering role during the years 1899–1914 in Canada’s early securities market. Working in a city with a concentration of financial services, Pellatt was for a time an extraordinary intermediator, with an abundance of conflicts. His methods were standard, though often pushed to the extreme by a sharp mind trained in speculative investment manoeuvre. Efforts to credit him with foresight for his role in bringing electricity to Toronto cannot fully discharge him of monopolistic intent. He had no rational plans for long-term solvency. It was Pellatt’s roguish behaviour that came to define his reputation. Set against the backdrop of Casa Loma and other evidence of uninhibited spending and self-promotion, his collapse was spectacular.

In his corporate capacities, Sir Henry Mill Pellatt contributed to or wrote many annual reports. A number of these, as well as some letters and speeches, were published. His report as commander of the Canadian coronation contingent of 1902 appears as app.B of the report of the general officer commanding in Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1903.

Material relating to Pellatt can be found in the Henry M. Pellatt fonds at AO (F 253) and in the F. W. Borden fonds at NSA (MG 2, vols.63–223). The Minutes of evidence (4v.) and Report of the royal commission on life insurance were published in Ottawa in 1907. The latter also appears in the Sessional papers for 1906/7. The [Hearing and evidence] (18v. in 2) and Interim report of the royal commission on the Home Bank were published in Ottawa in 1924. The report also appears in the Sessional papers for 1924. The letter-books (1901–39) of the Toronto Electric Light Company were examined at the Toronto offices of Hydro One Inc. through a request for access to information. As a result of digitization, newspapers online yield much new information on Pellatt’s career.

Any study of the man must come to terms with his formidable residence, Casa Loma, owned by the City of Toronto and now operated by the Liberty Entertainment Group as a tourist attraction, special-event facility, and museum. Over time it has accumulated material on Pellatt as well as original furnishings, artefacts, and artwork. Accessible sources are the website www.casaloma.org and two illustrated books: J. E. Crosbie, Decorative arts at Casa Loma ([Toronto], 2004) and Bill Freeman, Casa Loma: Canada’s fairy-tale castle and its owner, Sir Henry Pellatt, with photographs by Vincenzo Pietropaolo (Toronto, 1998; repr. 2012). Casa Loma’s files on Pellatt were made available by its former curator, Joan E. Crosbie. The castle also houses the museum of the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada. The Catalogue of the valuable contents of Casa Loma, Toronto, Ontario for the sale in June 1924 was examined at the library of the Royal Ont. Museum (Toronto). The author acknowledges the assistance provided by Joan E. Crosbie and Robert G. Hill.

Anglican Church of Can., Diocese of Ont. Arch. (Kingston, Ont.), St George’s Cathedral, Reg. of baptisms, 7 March 1859. AO, F 5. Girl Guides of Can. National Arch. (Toronto), Early corr., box 8, file 1. Royal Ont. Museum, Registration Dept., Sir Henry Pellatt file. Trinity College Arch. (Toronto), Office of the Secretary of Corporation fonds, Minute books, 1895–1912. Univ. of Cambridge, Churchill Arch. Centre (Cambridge, Eng.), BULL 4/5 (Sir William Bull papers, Diary and corr.). Daily Mail and Empire, 1881–1914. Financial Post (Toronto), 1907–22. Gazette (Montreal), 1906–37. Globe, 1867–1936. Globe and Mail, 1936–39. Monetary Times (Toronto), 1897–1929. New York Times, 1880–1939. Toronto Daily Star, 1895–1945. World (Toronto), 1906–19. C. W. Allen, Volunteer land grants, scrip, and pensions … (Toronto and Montreal, 1885). Christopher Armstrong, Blue skies and boiler rooms: buying and selling securities in Canada, 1870–1940 (Toronto, 1997). Christopher Armstrong and H. V. Nelles, “The rise of civic populism in Toronto, 1870–1920,” in Forging a consensus: historical essays on Toronto, ed. V. L. Russell (Toronto, 1984), 192–237. W. T. Barnard, The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada, 1860–1960: one hundred years of Canada (Don Mills [Toronto], 1960). Bright lights, big city: the history of electricity in Toronto (Toronto, 1991). Canada Gazette, 1898–1929. Canadian annual rev., 1901–26/27. Ramsay Cook, “Stephen Leacock and the age of plutocracy, 1903–1921,” in Character and circumstance: essays in honour of Donald Grant Creighton, ed. J. S. Moir (Toronto, 1970), 163–81. William Dendy et al., Toronto observed: its architecture, patrons, and history (Toronto, 1986). Directory, Toronto, 1861/62–1939. I. M. Drummond, “Canadian life insurance companies and the capital market, 1890–1914,” Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science (Toronto), 28 (1962): 204–24. Electrical News (Toronto), 1896–1913. C. A. S. Hall, “Electrical utilities in Ontario under private ownership, 1890–1914” (phd thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1968). W. H. P. Jarvis, Don Quixote in finance or has Canada a Medici?: a tale of treasons, stratagems and spoils ([Toronto, 1920?]). Journal of Commerce (Gardenvale, Que.), 1921, 1928. Maclean’s, 1920. N. M. MacTavish, “Henry Mill Pellatt: a study in achievement,” Canadian Magazine, 39 (May–October 1912): 109–19. “The makers of electrical Canada: Col. Sir Henry Mill Pellatt, c.v.o.,” Electrical News (Toronto), 22 (1913), no.12: 106–14. R. C. Michie, “The Canadian securities market, 1850–1914,” Business Hist. Rev. (Cambridge, Mass.), 62 (1988): 35–73. Desmond Morton, Ministers and generals: politics and the Canadian militia, 1868–1904 (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1970). H. V. Nelles, The politics of development: forests, mines & hydro-electric power in Ontario, 1849–1941 (Toronto, 1974). Ont., Legislature, Sessional papers (annual reports of the Bureau of Mines, 1906–20). Carlie Oreskovich, Sir Henry Pellatt: the king of Casa Loma (Toronto, 1982). The related website is www.kingofcasaloma.com. Christine Page, “A history of conspicuous consumption,” in Meaning, measure, and morality of materialism, ed. Floyd Rudmin and Marsha Richins (Provo, Utah, 1992), 82–87. A. S. Thompson, Spadina: a story of old Toronto (new ed., Erin, Ont., and Niagara Falls, N.Y., 2000). Toronto City Council, Minutes of proc. (Toronto), 1883–1912 (copies at the City of Toronto Arch., Research Hall library). J. F. Whiteside, “The Toronto Stock Exchange to 1900: its membership and the development of the share market” (ma thesis, Trent Univ., Peterborough, Ont., 1979).

Cite This Article

David Roberts, “PELLATT, Sir HENRY MILL,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 16, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/pellatt_henry_mill_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/pellatt_henry_mill_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | David Roberts |

| Title of Article: | PELLATT, Sir HENRY MILL |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2018 |

| Year of revision: | 2018 |

| Access Date: | February 16, 2026 |