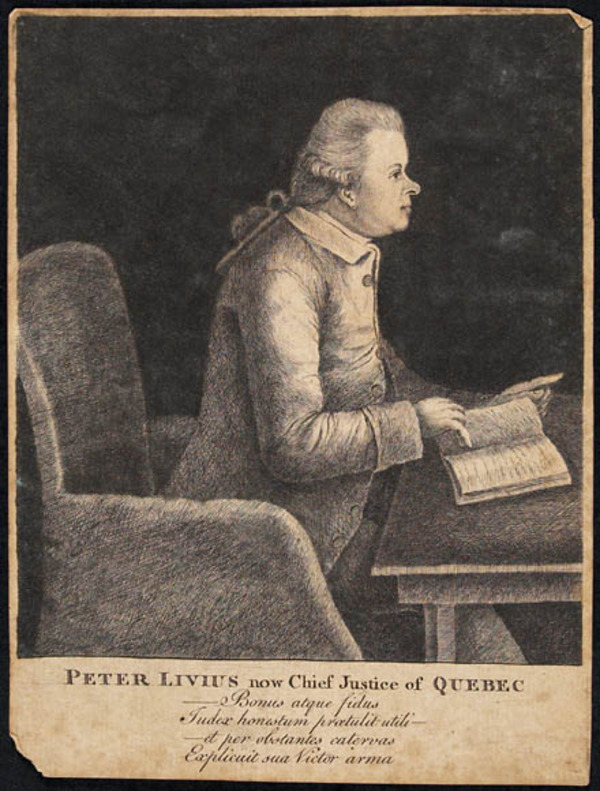

LIVIUS, PETER, chief justice of Quebec; b. 12 July 1739 at Lisbon, Portugal, son of Peter Livius; d. 23 July 1795 on his way to Brighton, England.

Peter Livius was the sixth child of a Hamburg German employed in the English factory at Lisbon. His English mother sent him to school in England where, about 1758, he married Anna Elizabeth, daughter of Colonel John Tufton Mason. This marriage was the foundation of his personal fortune.

In 1763 Livius moved to New Hampshire, where his wife’s family had large land claims. He established himself in lavish style near Portsmouth and from the first showed a marked ability to generate personal animosities; his Portuguese birth and ostentatious living were not to be forgiven. He gained his credentials in colonial society by a gift of books to Harvard College in 1764 and received an honorary ma three years later. In September 1765 his English connections obtained for him an appointment to the council of New Hampshire, and in 1768 he became justice of the Inferior Court of Common Pleas. He was accused of partiality as a judge, even of counselling litigants who were to appear before him. Governor Benning Wentworth, with whom he quarrelled over land grants, considered his political conduct to be factious and self-serving, alleging that he had been “a principal Abettor in the Disturbances at the Time of the Stamp Act” and had ever since been ready to court popularity in a manner unbefitting a judge. In 1772 Wentworth removed Livius from the bench.

Livius went to London to fight his dismissal, representing himself as the victim of the Wentworth family compact. The affair was widely reported in the colonial press. The Board of Trade accepted his charges, but the Privy Council upheld Wentworth’s decision. He went to work to improve his credentials in England by a gift of elk horns to the Royal Society, which made him a fellow in 1773 for being “well versed in various branches of Science.” He studied law at the Middle Temple and was called to the bar in 1775; an honorary dcl from Oxford University followed immediately.

Livius still planned to return to New Hampshire with honour vindicated, and he persuaded the secretary of state for the American Colonies, Lord Dartmouth, that he should be appointed chief justice with a salary paid directly by the crown. Wentworth protested vehemently and successfully; Livius had to settle for the posts of judge of the Court of Common Pleas and judge of the Court of Vice-Admiralty, in Montreal. Dartmouth wrote Governor Guy Carleton* that a man of Livius’ abilities deserved a place on the Council and a seigneury. Livius arrived at Quebec on 4 Nov. 1775, just in time to experience the siege by the Americans [see Richard Montgomery]. He later wrote of serving “day and night . . . with a musquet on my shoulder as a private soldier.” He was rewarded with the office of chief justice in August 1776 and, ex officio, a senior place in the Council. He tried his hand at secret correspondence with the rebel general John Sullivan, urging him to turn over New Hampshire to the royal forces. The letter was intercepted and widely published; the new state responded by confiscating his estates and banishing him forever.

Within the beleaguered province of Quebec, history began to repeat itself as once again Livius generated strong animosities. Carleton had had his own nominee for the post of chief justice and complained bitterly that Livius had been sent “to administer justice to a people, when he understands neither their laws, manners, customs nor their language.” Late in the summer of 1777 Livius clashed in the Council with Lieutenant Governor Hector Theophilus Cramahé who was replacing Carleton during the latter’s visit to the west of the province. Later, when Cramahé arrested the Quebec tanner Louis Giroux and his wife for seditious utterances and lodged them in a military jail, Livius protested bitterly at this invasion of his civil authority. Governor Carleton supported the chief justice in this case, but early in 1778 they too came to a parting of the ways. Carleton, anxious to maintain the uneasy calm of wartime Quebec, had never revealed his instructions to the Council, instructions which would have made concessions to the English minority and introduced habeas corpus with its guarantee against arbitrary imprisonment. Sensing this omission, Livius at first tried privately to persuade Carleton to reveal his instructions; unsuccessful, he publicly moved in Council in April 1778 that the instructions be produced. The motion was lost, and Livius proceeded to move a remonstrance against Carleton’s practice of routinely consulting a small number of councillors of his choice rather than the full board. At the end of that same month Livius made a powerful summation in a civil suit involving Jean-Louis Besnard, dit Carignant, and Richard Dobie* which persuaded the Council, sitting as an appeals court, to find for Dobie. Carleton had earlier and quite improperly expressed his opinion to Livius that Dobie was at fault. The day following Dobie’s vindication, 1 May 1778, Carleton dismissed Livius as chief justice without giving him any reasons for his removal.

On 31 July Livius left to plead his case in London, in the same convoy as Carleton but on a different ship. When asked by the Board of Trade to give grounds for his action, Carleton replied that he considered Livius “turbulent and factious,” and a danger to the peace of the colony. A committee of the Privy Council restored Livius to office in March 1779, but he showed a marked reluctance to return to Quebec. He feared another collision, this time with the new governor, Frederick Haldimand, who was reputedly far less concerned with civil liberties than Carleton had been. Livius never saw Quebec again, for when he finally set sail in the autumn of 1780 his ship was beaten back from Newfoundland.

In the spring of 1782 Livius brought suit against Carleton for damages. He refused to go to Quebec unless the British government pledged that he would not be dismissed without a warrant from home. He claimed payment of arrears of salary, plus the expenses incurred in defending himself, and he wanted the seigneury and ironworks of Saint-Maurice as additional compensation. The secretary of state for the Home Department, Lord Sydney, who had to fend off these demands, found Livius pompous and unpleasant: he “asks a Silk Gown [kc] & Money, the Lord knows what . . . . He is a talking Man of Parade, with a strange Cast of Eye.”

In December 1784 Livius first heard rumours that he was to be replaced in office by the former chief justice of New York, William Smith. He tried negotiating with Smith through Dr Thomas Bradbury Chandler, stating that he would rather have £600 a year in England than £1,500 in Quebec; he forgot to say that he was only on half pay since the remainder went to the three provincial judges who held the chief justice’s place in commission. The prolonged absence of a chief justice seriously weakened the judicial system of Quebec at a difficult time. Carleton chose Smith for the office, and in 1786 Livius lost a position that for eight years had been nothing but a hollow title.

From then until his death Livius existed in obscurity, yet another disappointed place-seeker. He presented William Pitt with a list of 50 offices he would accept, but he several times declined a pension. He claimed no compensation for his losses as a loyalist and, when no new office was forthcoming, agreed to accept a pension in June 1789.

Livius is a difficult man to evaluate. In the great crises of his life, such as the controversies over Wentworth’s land holdings and Carleton’s instructions, he was technically in the right but reckless to a fault. He could also be devious in political manœuvring as was shown quite explicitly in New Hampshire and insinuated in Quebec. Above all, he was a foreigner who tried to gain acceptance by following the norms of the English establishment: marriage into a family on the fringes of the aristocracy, honorary degrees from Oxford and Harvard, and membership in the Royal Society and Middle Temple. But he was never accepted as an Englishman, and this fact put a sharper edge on every controversy in which he engaged. Ironically, it was another foreigner in English service, Frederick Haldimand, who, grasping for the ultimate disparagement, raised the question whether a Portuguese of German parentage could hold any office under the crown without being prosecuted at the whim of a common informer.

The memorial of Peter Livius . . . to the lords commissioners for trade and plantations; with the governor’s answer, and the memorialist’s reply . . . also their lordships report thereon . . . ([London], 1773). Proceedings between Sir Guy Carleton, K.B., late governor of the Province of Quebec, and Peter Livius, esquire, chief justice of the said province . . . ([London], 1779). Proceedings in the case of Peter Livius ([London, 1790]). [William Smith], The diary and selected papers of Chief Justice William Smith, 1784–1793, ed. L. F. S. Upton (2v., Toronto, 1963–65), I, 166–68, 174–75; II, 21, 115. Shipton, Sibley’s Harvard graduates, XIII, 261–70. Burt, Old prov. of Que. (1933), 267–75. Neatby, Administration of justice under Quebec Act, 66–86. A. L. Burt, “The tragedy of Chief Justice Livius,” CHR, V (1924), 196–212. R. P. Stearns, “Colonial fellows of the Royal Society of London, 1661–1788,” William and Mary Quarterly (Williamsburg, Va.), 3rd ser., III (1946), 208–68.

Cite This Article

L. F. S. Upton, “LIVIUS, PETER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 5, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/livius_peter_4E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/livius_peter_4E.html |

| Author of Article: | L. F. S. Upton |

| Title of Article: | LIVIUS, PETER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | April 5, 2025 |