Source: Link

HUNTER, ADELAIDE SOPHIA (Hoodless), educator and author; b. 27 Feb. 1858 (often given incorrectly as 1857) on a farm near St George in Brant County, Upper Canada, 12th child of David Hunter and Jane Hamilton; m. 15 Sept. 1881 John Hoodless in Cainsville, near Brantford, and they had two sons and two daughters; d. 26 Feb. 1910 in Toronto, and was buried in Hamilton.

Little is known about Addie Hunter before she entered public life in 1890, when she adopted the more formal Adelaide. Her paternal grandparents had migrated to Peel County in Upper Canada from County Monaghan (Republic of Ireland) in 1836. Her father died some four months before her birth. She appears to have received little education beyond elementary school. Addie remained on the family farm until she and her husband moved in 1881 to Hamilton, where John Hoodless, the son of Joseph Hoodless, a prominent Hamilton furniture manufacturer, joined his father in business. At this time she converted from the Presbyterian to the Anglican denomination and became actively involved in Hamilton’s Church of the Ascension. Their fourth child, a son, died in 1889.

Adelaide Hoodless ventured from the confines of her home in September 1890 to become second president of the Hamilton Young Women’s Christian Association. In that capacity she attended the World’s Congress of Representative Women held in May 1893 in conjunction with the Columbian exposition in Chicago. Discouraged by the reception that Canadians received as a result of their lack of national organizations, she returned with a determination to alter the situation. For several months she worked to help create the National Council of Women of Canada. At its inaugural meeting in Toronto that October she was elected treasurer and was instrumental in persuading Lady Aberdeen [Marjoribanks*] to become president. A month later Hoodless established Hamilton’s Local Council of Women and began serving as its corresponding secretary. In December she organized in Toronto the founding meeting of the national YWCA, of which she became first vice-president and then, in January 1895, president. When Lady Aberdeen established the Victorian Order of Nurses for Canada, Hoodless assisted the initiative in Hamilton.

Hoodless was concerned not only about the lack of organization among women but also about the effects upon them of industrialization and urbanization. No longer were there as many girls trained in domestic arts as there had been when she was young. Goods once manufactured in the home were now usually purchased from outside. Women increasingly sought employment in offices and factories, a development she considered to be against their predestined roles as wives and mothers. At the same time, the application of scientific knowledge to foods, begun in the United States in the 1880s, had created new disciplines such as nutrition and sanitation. For Hoodless, introducing science to household duties extended the possibility of reversing trends that diminished women’s familial role and led large numbers of them to seek paid employment outside the home. A new discipline then emerging – variously called domestic science, household science, and eventually home economics – would, she thought, provide to girls the equivalent of industrial arts for boys.

While Hoodless was influenced by pedagogical developments in the United States, the British popular philosopher Herbert Spencer left the most lasting imprint on her educational outlook. Like him, she saw education as a means to an end, and she stressed its instrumental role over the intrinsic value of acquiring knowledge. Practical results were more important to her than the sharpening of critical faculties. She extended his argument by maintaining that the school system had been created by men for males. Education needed to be made more practical and more attuned to socializing children to distinct gender roles from the earliest years. In this larger adjustment, home economics held a key position. For Hoodless, it was more important than industrial arts for boys because the educational system had done such a disservice to young women. Instruction in home economics would improve the position of women in society, strengthen the family, and deter women’s suffrage. Hoodless opposed female enfranchisement on the grounds that women exercised their influence through their sons and husbands. Any girl or woman, she declared in her speech “New methods in education,” “who has been brought face to face with the great truths presented through a properly graded course in domestic science or Home Economics in its wider interpretation, will never be found in the ranks of the suffragettes.” Hoodless was even more condemnatory of advocates of prohibition, denouncing them as “temperance cranks.”

In September 1894, while commercial courses were being phased out at the Hamilton YWCA because Hoodless felt they were unsuited to the role women should play, she opened on its premises Canada’s first secular school of domestic science. She then began a multi-pronged campaign to gain acceptance for the subject in local schools, the provincial educational curriculum, and teacher-training institutions.

In preparing initiatives for women that would require money, Hoodless and her supporters encountered opposition at the local level based on gender, class antagonisms, and political conflicts. The recent introduction of kindergartens in Hamilton had proved costly. Elected representatives were reluctant to spend more money to teach skills that had once been acquired exclusively at home. Labour was initially as suspicious of home economics as it was of industrial arts, fearing the implementation of a two-tiered educational system that would place working-class children at a disadvantage. Conservatives opposed Adelaide Hoodless on political grounds: although John Hoodless was a Conservative, she had retained her commitment to Liberalism and enjoyed strong connections with the party. In spite of the opposition the Hamilton Board of Education agreed to fund the teaching of the new subject under the auspices of the Hamilton YWCA in 1897, but the experiment was not renewed the following year. Local officials wanted the province to bear the cost of this program and noted that the trial had failed to include a sufficient number of working-class students.

In Liberal politician George William Ross*, Ontario’s minister of education (1883–99) and later its premier, Hoodless found a firm ally who admired her persistence and determination. Beginning in 1894 she excited his interest in special instruction for girls and led him to tour new facilities in the United States. Although the Department of Education provided no money initially, regulations were issued in 1897 governing the curriculum for home economics where local school boards chose to introduce it and allowing for the examination of teachers in this subject. At the minister’s urging, Hoodless published a textbook, Public school domestic science, the following year that was a compilation of recent scientific findings derived from the application of chemistry to the understanding of food values, preservation, and preparation. It was geared to the audience that became her first preoccupation, young women training to become teachers. Moreover, the minister employed Hoodless to prepare occasional reports for publication on the teaching of home economics in Ontario, the first of which was published in 1897. The department also assumed the expenses she incurred on trips around the province to persuade local school boards to begin instruction in home economics. She excelled in public speaking and knew how to appeal to her largely male audiences. While she castigated the school system for its injustice to women, she extended to her listeners, in a way they could understand, the comforting reassurance that home economics would restore the old sexual division of labour. Between 1894 and 1897 she gave over 60 addresses.

One speech resulted in her becoming venerated worldwide as founder of an organization to advance the education of rural women. In December 1896 she spoke at the Ontario Agricultural College [see William Johnston*] in Guelph. One of her listeners, Erland Lee, secretary of the Farmers’ Institute of South Wentworth, invited her to Stoney Creek, near Hamilton, to address that group’s ladies’ night on 12 February. As a result of her suggestion that the women present organize to foster self-education she was asked to attend a meeting a week later that resulted in the founding of what became the Women’s Institute of Saltfleet Township. On 25 February Christina Ann Smith, wife of farmer (and later senator) Ernest D’Israeli Smith*, was elected president, and Adelaide Hoodless honorary president. The idea quickly spread, benefiting in Ontario from the financial and organizational support of the provincial Department of Agriculture. Within decades Women’s Institutes were operating in many parts of the world and Hoodless enjoyed lasting fame as the movement’s founder.

Success on a number of fronts led Hoodless to aspire to close the existing school of domestic science in Hamilton and to replace it with the foremost institute for training home economics teachers in the country, one with the best facilities, the highest admission standards, and the most rigorous course of study. A campaign to raise $15,000 to construct a new building began in 1896, but despite a large donation from Sir Donald Alexander Smith* (later Lord Strathcona), who also promoted cadet training, failed to reach its goal. The Ontario Normal School of Domestic Science and Art, accredited by the government, opened in renovated YWCA premises in February 1900 with Hoodless as president. Teachers educated in the United States and Britain had been hired, and local medical doctors and instructors from the OAC were brought in as supplementary staff. Students took some of their classes at another teacher-training institute, the Ontario Normal College, also in Hamilton. Nellie Ross, the premier’s daughter, was among the first to enrol. The most illustrious graduate would be Katherine Anderson Fisher, of Stratford, who was director of New York’s Good Housekeeping Institute from 1924 to 1953.

Buoyed by connections with the National Council of Women and the Department of Education, Hoodless emerged as the pre-eminent advocate of home economics in Canada. She carried her messages to other provinces, visited the United States frequently, and attended the International Congress of Women in London in 1899. At home, however, she began to encounter set-backs. Although her school had received the first provincial grant for training home economics teachers in 1900, the appropriation which Hamilton City Council had accorded it that year was withdrawn in 1901 amid allegations of élitism. Lord Strathcona contributed to the school’s operating expenses but it was unable to meet its budget. At the same time, other women active in the home economics movement, such as Alice Amelia Chown* and Alice Ravenhill, were beginning to comment publicly on Hoodless’s lack of educational qualifications and “mental training” for the agenda she had set for herself. After John Hoodless experienced severe business problems she resigned as treasurer of the National Council of Women in 1901, but continued on the executive after becoming provincial vice-president for Ontario the following year.

Frustrated with developments in Hamilton, Hoodless made common cause with James Mills*, president of the OAC, who desired to see a home economics faculty established there in emulation of certain American universities. To achieve this end, Mills had sought financial support from Sir William Christopher Macdonald*, the tobacco magnate, who had shown philanthropy towards educational initiatives, especially in industrial arts. Mills was now joined in these efforts by Hoodless, who believed that agriculture and household arts were the two areas that offered unlimited opportunities to women. In 1901 she travelled to Montreal to meet Macdonald. Her suggestions fitted in well with the plans he had formulated with his educational adviser, James Wilson Robertson*, to create a teacher-training school to improve rural education in eastern Canada. Early in 1902 a grant to establish the Macdonald Institute of Home Economics in association with the OAC was announced and construction begun. The facility, which included a residence, was intended to provide teacher training in nature study, industrial arts, and home economics, as well as a shorter course in home economics for farmers’ daughters. Later, arrangements were made to have teachers from the Maritime provinces and the Protestant school system in Quebec study at the new institute until McGill University’s Macdonald College was completed. Hoodless helped Mills design the physical facilities and the curriculum.

The Ontario Normal School of Domestic Science and Art was closed in June 1903, its deficit assumed by the Department of Education. The program moved to the OAC, where classes commenced in unfinished premises in September. (The formal opening was held in December 1904.) Contrary to what Hoodless had hoped for, the Macdonald Institute was placed under the Department of Agriculture, which ran the OAC, rather than the Department of Education. Mary Urie Watson, who had headed the Hamilton school, became the institute’s lady principal; William Hawthorne Muldrew, formerly a high school principal in Gravenhurst, served as dean.

When her husband’s business had soured in 1901, Hoodless had attempted to find ways to assume financial responsibility for their family. She pleaded to be appointed provincial director of domestic science, but Richard Harcourt*, who had succeeded Ross as minister of education, agreed only to supply her with a temporary salary of $600. Her request to develop a graded curriculum in home economics was also denied. In the light of continuing financial problems at the school of domestic science and its impending move to Guelph, she resigned as president of the Hamilton YWCA in September 1902. The turmoil of these events caused a nervous breakdown around the end of the year. When she failed to get elected in a large slate for the YWCA’s board of directors early in 1903, she threw a temper tantrum and “bounced out of the building bristling with indignation.”

Through the good offices of Watson, early in 1904 Hoodless was given a short course to teach at the Macdonald Institute on ethics and the home. Because her teaching consisted of rehashing old reports and repackaging her common themes in sanctimonious trappings, Muldrew cancelled it in August. Accustomed to issuing commands rather than following orders, Hoodless had already experienced difficulties at the new school. In April she had lamented to Harcourt: “It seems hard that women have to fight for every inch of justice for their work, and when men ask for a thing it is granted without our side being so much as consulted.” After Muldrew died in October, the OAC’s new president, George Christie Creelman, allowed her course to be restored, and she presented it as annual lectures until the end of her life.

Hoodless hoped to secure for the Macdonald Institute the exclusive right to certify home economics teachers. She disparaged initiatives elsewhere in the province, notably in Ottawa and at the University of Toronto, where the household science program had been accepted in 1902 following a gift from Lillian Frances Massey* Treble. Hoodless was so critical of the Toronto undertaking in the draft of her 1904 report to the Department of Education that Harcourt had to request formally that she include a favourable account of it in the published version; indeed, this report was so excessively coloured by her personal opinions that her agreement with the department was terminated. Although the Ontario government had introduced grants for home economics instruction in the schools in 1903 and allowed it as an option in the elementary curriculum the following year, it would not acknowledge a special place for the Macdonald Institute in teacher training. Late in 1903 Hoodless contemplated moving to the United States, where she felt she was better appreciated, but averred that family ties restrained her. Another bout of poor health, which she described as a “long tedious illness,” ensued early in 1905.

During the last five years of her life Adelaide Hoodless lessened her commitments as she was increasingly pushed to the periphery of the home economics movement by better-qualified individuals. She spoke more infrequently to school boards, but annually gave several public lectures and, under the auspices of the Department of Education, inspected provincial teacher-training facilities. She retained her link with the National Council of Women until 1908 when she resigned from its executive and as convenor of its domestic science committee, a position she had held since the committee’s inception in 1901.

A speech she presented at the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh in 1908 led to her appointment a year later as adviser to the Carnegie Technical Schools. Also in 1908 she accepted the challenge of reporting on American trade schools for the Ontario government. After meeting Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier* socially in 1909, she wrote to him with great prescience of the need to establish a national research school of technology in Ottawa. Canada, she argued, had failed to develop its own scientific and technical expertise while countries such as Germany had promoted native talent through national laboratories. Laurier replied that education fell solely within provincial jurisdiction.

In 1909 Hoodless prepared a report for the Ontario government concerning trade schools and elementary education. It lacked coherence, failing either to define its subject or to deal adequately with it. Although she reviewed American facilities, she made no significant recommendations. To the end she remained a publicist rather than a thinker. On 26 Feb. 1910 she was repeating her old themes concerning women and industrial life before the Women’s Canadian Club in Toronto when she collapsed and died of heart failure.

Adelaide Hoodless was remarkable in that she overcame the limitations of her background, personality, and intelligence to emerge into the public spotlight. Her marriage to John Hoodless was important to her in many ways. Not only did it generally provide financial security, but the fact that her husband limited his ambitions to local political, religious, musical, and fraternal involvements gave her free rein to pursue her own goals. Moreover, he and their children afforded Adelaide the emotional support she needed when she extended herself too far. Although she enjoyed the public recognition she received, she always claimed her family as her first loyalty and responsibility. Her son, Joseph Bernard, graduated from the OAC in 1905, joined his father’s business, served in World War I, and taught at his alma mater before his death in 1929. Both daughters married; neither sought the prominence her mother had attained.

Despite contradictory elements in her thoughts on society and education, Adelaide Hoodless’s conservative message disguised as educational innovation was warmly received in certain constituencies. Women at the National Council and men in business, government, newspapers, and boards of education found her call for a restoration of women through home economics a reassuring response to the movement of women into the workforce and the rising demand for female enfranchisement. The insertion of home economics and industrial arts into the provincial curriculum was a major achievement Hoodless shared with others, notably John Seath, Ontario’s superintendent of education. The development was significant in two ways: not only did it introduce into the school system the more practical view of education that Hoodless advocated but it also institutionalized gender distinctions in provincial schools.

Adelaide Hoodless was exceptionally adept at discerning contemporary trends and adapting new ideas to the Canadian sphere. In helping to found two national women’s organizations and in suggesting the creation of Women’s Institutes she left a distinct imprint on her own and subsequent generations. As the institutes spread around the world, Adelaide Hoodless became recognized internationally as one of Canada’s most prominent women. In 1959 the Federated Women’s Institutes of Canada purchased the farmhouse in which she had been born and converted it into a historic site.

Training teachers in home economics always remained the primary concern of Adelaide Hoodless. In establishing her own school in Hamilton in the face of adversity and in securing its transfer to Guelph she produced a vehicle as formidable as the Women’s Institutes in perpetuating her ideals. She was among the last of the non-professionals to have a significant impact on the provincial school system in Ontario.

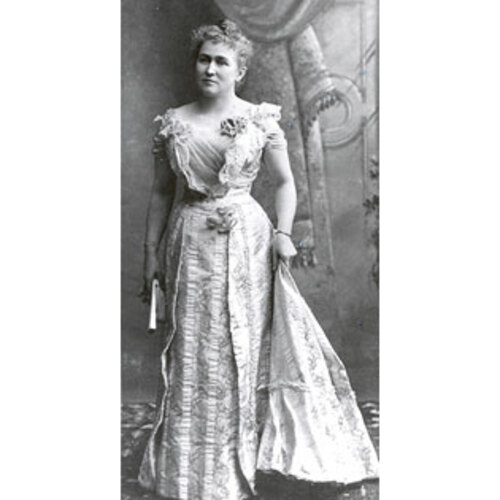

A portrait of the subject by John Wycliffe Lowes Forster*, c. 1907, is reproduced in colour in Cheryl MacDonald, Adelaide Hoodless: domestic crusader (Toronto and Reading, Eng., 1986); the original was donated to the Macdonald Institute, Univ. of Guelph, Ont.

Adelaide Hoodless is the author of a number of publications, including: “The relation of domestic science to the agricultural population,” Ont., Legislature, Sessional papers, 1897, no.17: 245–52; “A step in the right direction – the Saltfleet Women’s Institute” and “Organization in the rural districts,” Ont., Superintendent of Farmers’ Institutes, Report (Toronto), 1897–98: xxii–xxiii and 261–62; Public school domestic science (Toronto, 1898); “The labour question and women’s work and its relation to home life” and “Agriculture for women and the marketing of agricultural products,” NCWC Year book, 1898: 254–62 and 1900: 157–61; “The industrial possibilities of Canada,” NCWC, Women of Canada: their life and work; compiled . . . for distribution at Pan-American Exposition, Buffalo, 1901 ([n.p., 1901?]), 91–95; “Domestic science,” NCWC Year book, 1902: 117–20; “A new education for women,” Farmer’s Advocate and Home Magazine, 15 Dec. 1902; “Household science report,” Ont., Legislature, Sessional papers, 1904, no.12: 157–65; [Vice-president’s report], NCWC Year book, 1904: 40–41; “Home economics,” Dominion Educational Assoc., Proc. of the convention (Toronto), 1907: 191–96; and Report to the minister of education, Ontario, on trade schools in relation to elementary education (Toronto, 1909).

Adelaide Hunter Hoodless Heritage Homestead (St George, Ont.), Copy of marriage certificate; Hunter family bible. AO, RG 2, D-7, box 3; box 5, esp. Hoodless to Richard Harcourt, 6 Feb., 16 Dec. 1902; P-2, boxes 59–62, esp. files 86–87. HPL, Clipping file, Hamilton biog., Adelaide, J. B., John, and Joseph Hoodless; Hamilton – organizations and societies, Local Council of Women; Scrapbooks, Adelaide Hoodless. NA, MG 28, I 198, 9. St George’s Cemetery (St George), Tombstone of David Hunter. Univ. of Guelph Library, Arch. and Special Coll., Macdonald Institute coll., REI Mac A0055; XR 1 MS A001 (Hoodless family papers), including the text of Adelaide’s speech “New methods in education.” Globe, 28 Feb. 1910: 16. Toronto Daily Star, 28 Feb. 1910. World (Toronto), 28 Feb. 1910. A. A. Chown, The stairway, intro. Diana Chown (Toronto, 1988), xxiii–xxvi. Terry Crowley, “Madonnas before Magdalenes: Adelaide Hoodless and the making of the Canadian Gibson girl,” CHR, 67 (1986): 520–47; “The origins of continuing education for women: the Ontario Women’s Institutes,” Canadian Woman Studies (Downsview [Toronto]), 7 (1986), no.3: 78–81. Simon Goodenough, Jam and Jerusalem (Glasgow, 1977). Ruth Howes, “Adelaide Hunter Hoodless, 1857–1910,” The clear spirit: twenty Canadian women and their times, ed. Mary Quayle Innis (Toronto, 1966), 103–19. Wendy Mitchinson, “The YWCA and reform in the nineteenth century,” SH, 12 (1979): 368–84. E. C. Rowles, Home economics in Canada; the early history of six college programs: prologue to change (Saskatoon, Sask., [1964]). R. M. Stamp, The schools of Ontario, 1876–1976 (Toronto, 1982).

Cite This Article

Terry Crowley, “HUNTER, ADELAIDE SOPHIA (Hoodless),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hunter_adelaide_sophia_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hunter_adelaide_sophia_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Terry Crowley |

| Title of Article: | HUNTER, ADELAIDE SOPHIA (Hoodless) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |