Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

HAMEL, THÉOPHILE (baptized François-Xavier), painter; b. 8 Nov. 1817 at Sainte-Foy, near Quebec, one of nine children of François-Xavier Hamel, a farmer, and Marie-Françoise Routhier; d. 23 Dec. 1870 in Quebec.

On 16 May 1834, at age 16, Théophile Hamel became an apprentice to the most prominent artist at Quebec, Antoine Plamondon*, by a contract between Théophile’s father and the artist. Plamondon undertook, for a period of six years, to “show and teach him . . . the art of painting and everything involved therein, not concealing anything from him.” Until he was 22, Théophile worked under Antoine Plamondon, experiencing no other influence. It seems that the master’s touchy nature made it impossible for him to meet others in the profession. Hamel’s contract further stipulated that the young man must “not frequent taverns, gambling dens, or other houses of doubtful repute.”

Théophile Hamel began his career with encouragement from three leading social groups interested in art: the clergy, politicians, and businessmen. In October 1840 a correspondent of the Quebec Mercury reported that in Hamel’s studio he had seen a magnificent sketch of an ecclesiastic. The following year, Hamel painted a portrait of Abbé David-Henri Têtu (still hanging in the church of Saint-Roch at Quebec) and one of Amable Dionne*, a politician. In 1842, Mme Marie Bilodeau and her daughter Léocadie were portrayed with great delicacy of touch. Finally, during the same year, he did a large canvas, painted with bold strokes, on a religious theme inspired by a picture in the Desjardins collection [see Louis-Joseph Desjardins*], Jésus au milieu des docteurs. This canvas is still preserved in the church at Saint-Ours. Hamel’s principal themes were established; from then on he would not change.

As his master had done, Théophile Hamel decided to make a trip to Europe. On 10 June 1843 he sailed on the Glenlyon, a merchant ship bound for London. Tradition has it that he stayed mainly in Italy and Belgium, and spent some time in Paris. In fact the letters we possess concerning his journey prove that Théophile stayed in Rome from summer 1843 to summer 1845. In October 1844 a Canadian priest records meeting him in Rome, when, after a year and a half in Italy, he seems to have been experiencing financial difficulties. The priest launched a dramatic appeal to the Canadian government through Le Journal de Québec: “But must it be said? This young man is here in Rome at his own expense; . . . should not our government follow the example of the French government and the other governments who maintain so many resident students in Rome, and come to the aid of this brilliant young artist?” To support his request, the cleric even stated that the Accademia di San Luca would have awarded Hamel first prize if he had not been debarred because he had not participated in the work of the academy long enough.

This assertion raises the whole question of young Hamel’s artistic activity in Italy. In a letter of 26 Aug. 1843, the artist states that on his arrival in Rome he had been admitted to the various academies of painting, and had chosen the Académie Royale de France. But it is unlikely that Hamel was actually admitted to this academy: under the directorship of Victor Schnetz (1841–46), the academy had to face continuous financial difficulties; moreover, the Villa Medici, where the academy was housed, contained only five painting studios, and had so little space that Alexandre Cabanel’s arrival in 1845 as the sixth boarder created serious problems of accommodation. The Canadian priest’s letter of 19 Oct. 1844 speaks of the Accademia di San Luca. This academy, which had been founded in Rome around 1588, and had an unusual history, had declined and thus numerous private schools had been formed which called themselves academies. They were schools organized by artists in their own houses; it was easy to get oneself admitted to them. Several towns, including Florence, had the same system. Hamel may well have enrolled in these academies and followed their teaching.

From Rome, Théophile Hamel went directly to Venice, and there at the end of August 1845 he was busily copying Titians. Nothing is known of his movements in France and Belgium, but there are some fine works executed in Europe. The Madeleine Hamel collection at Quebec contains magnificent drawings and some water-colours. The spontaneity of certain sketches is in happy contrast with the stiffness of the majority of his pictures. What became of other works executed during his travels? No mention was made of them when he returned in August 1846. His arrival in Quebec was, however, widely commented on in the newspapers. All observed that the artist had travelled extensively, and stressed his long stay in Italy. Le Canadien’s note that he had brought back Italian and Belgian paintings was the only mention of his movements outside Italy. After 1870, simply on the basis of a notice published in Le Courrier du Canada (Quebec) the day after his death, all his biographers speak of his stay in Belgium. This stage in Hamel’s artistic training remains obscure, and the vigour of the great Flemish masters does not seem to have made much change in his style of painting. On the other hand, most of his portraits show the influence of Titian.

Barely a month after his return to Quebec, Théophile Hamel opened a studio at 13 Rue Saint-Louis. Every week-day, from nine in the morning to four in the afternoon, the public was invited to visit it. Fourteen months later, in the autumn of 1847, the painter went to live in Montreal and remained there for two and a half years.

The Quebec phase of Hamel’s career really began in October 1851, when he took up permanent residence in the city itself. Antoine Plamondon had already retired to Neuville and Cornelius Krieghoff* had not yet come to Quebec. On 9 Sept. 1857, at age 39, the already well-known artist married Georgina-Mathilde Faribault, daughter of Georges-Barthélemi Faribault, and they were to have at least five children; only two, Julie-Hermine and Théophile-Gustave, reached adulthood.

As a result of his work as an artist, Théophile Hamel was able to live comfortably; he bought a house, and a notarial register indicates a large number of financial transactions. For example, in 1858 he lent his brothers, who were trading partners, the tidy sum of £2,000. He received appeals from distant parish councils in Quebec – that of Rimouski, for instance, to which he loaned £200 and also from neighbouring farmers. Between 1863 and 1869 he granted several loans, amounting to £1,600. For several years after his death on 23 Dec. 1870 his widow continued to carry out such transactions.

In addition to prosperity, Théophile Hamel had won the respect of the élite. His work merits careful scrutiny for the close relation between its themes and the social groups from which his commissions came. He was appointed official portrait painter by the government in June 1853, and entrusted with the task of painting the portraits of the speakers of the assemblies and legislative councils since 1791. This honour was equivalent to recognizing him as the best painter of his day. The first series of portraits consisted of 14 canvases representing the speakers of the assembly. To fulfil these orders, he found it necessary to travel outside Quebec. In October 1853 he went to New York to do the portrait of Marshall Spring Bidwell*, who had been speaker of the assembly of Upper Canada. That year he painted Sir Allan Napier MacNab of Canada West, and had the portrait lithographed. As the government travelled between Quebec and Toronto, the artist was obliged to follow it to execute his commissions. Since several speakers had died or were living abroad, Hamel had to be content with copying family paintings of Alexander McDonell*, Levius Peters Sherwood*, Jean-Antoine Panet*, Joseph-Rémi Vallières* de Saint-Réal, Michel-Eustache-Gaspard-Alain Chartier* de Lotbinière, and Augustin Cuvillier*. The complete assignment was dispatched to Toronto at the end of November 1856. From then on he was able to concentrate on the portraits of the speakers of the Legislative Council. In December 1856 nine portraits were finished. On 30 Jan. 1858 a second series of 14 portraits was completed, eight copied from family portraits and six from life. Five speakers could not be portrayed because there was no documentary material. These two series of portraits were to form “the nucleus of a national and historical gallery,” to which some wanted to add the canvases of Paul Kane*. When the government settled in Ottawa in 1866, the portraits were taken there. After surviving the fire which destroyed the parliament buildings in 1916, the majority were hung in the corridors surrounding the Senate and the House of Commons, where they can still be seen. Others are in the National Gallery of Canada.

Hamel also painted for the government a series of historical portraits: Champlain*, Charlevoix*, Montcalm*, Wolfe*, Lévis*, Murray*, Sir George Prevost*, John Neilson*, Andrew Stuart*, and Louis Bourdages*; in March 1866 these were added to numerous others already hanging in the parliament buildings. His portrait of Jacques Cartier* is a special case. On his return to Canada in 1846, Hamel had made a copy based on a copy of an original attributed to François Riss and preserved at Saint-Malo; Hamel’s painting had been sent to the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec. This copy was reproduced on dollar bills and stamps, and in text-books. Hamel seems also to have made several replicas in oils, since in 1860 the Legislative Assembly and in 1870 the Institut Canadien at Quebec each received one.

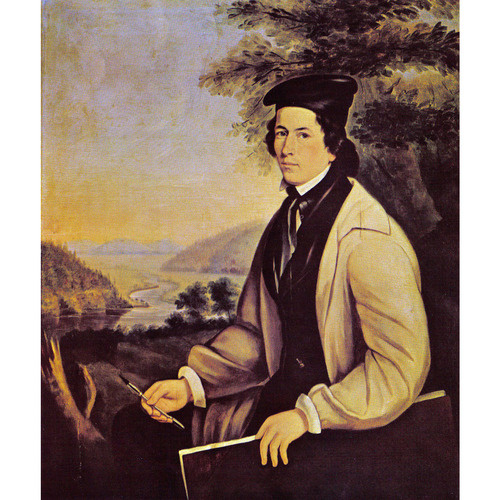

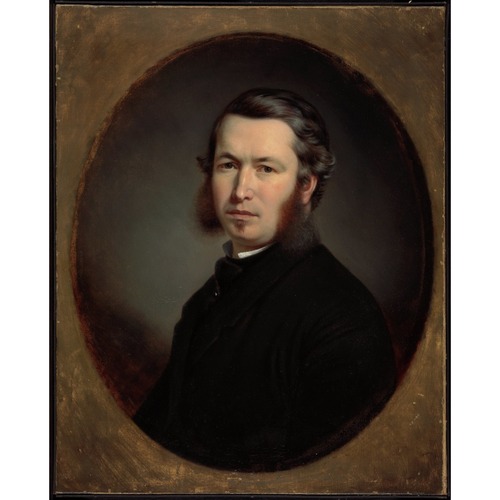

The aristocracy and bourgeoisie provided further scope for Hamel’s activity as a portrait painter. In 1841 he had done portraits of Charles-Hilaire Têtu and of his wife. During his stay at Montreal, in response to the Mailhot family’s request, he painted Dr Alfred Mailhot, who died in 1847 during the typhus epidemic. In 1849 he put on canvas the features of the future mayor of Montreal, Charles Wilson*. The chief justice, Jean-Roch Rolland, had his portrait done in 1848. In 1853 a subscription was started at Quebec to pay for the portrait of mayor Narcisse-Fortunat Belleau*. A similar subscription was undertaken in 1862 for Mayor Thomas Pope. Dr Marc-Pascal de Sales Laterrière* and his wife Eulalie-Antoinette Dénéchaud each ordered their portrait during the year 1853. Joseph Morrin, a doctor and seventh mayor of Quebec from 1855 to 1858, was also painted by Hamel. Several members of the Hamel family and intimate friends such as Cyrice Têtu and his wife were preserved for us by his brush. His parents, painted in 1843, are perhaps, along with Mme Louise Racine, the sole representatives of the habitants. We know of only one picture of his wife, and one of his father-in-law, the bibliographer Georges-Barthélemi Faribault. On several occasions Hamel painted his own children, those of his brother Abraham, and those of his nephew Ernest Hamel. Of all these portraits from his own family group, three self-portraits painted in 1837, 1846, and 1857 have given rise to the most discussion.

Hamel’s talents as a portrait painter also tempted the clergy: abbés, bishops, deans, and vicars general proved eager to display the trappings their dignity. Several founders were also portrayed, at the request of grateful church people: Louis-Jacques Casault, the first rector of the Université Laval; Abbé Joseph-David Déziel* of Lévis, with the plans of the college he had just established; the Reverend Patrick McMahon*, with his hand resting on the plans of St Patrick’s Church. The newspapers of the period all mention the picture of Abbé Charles-Paschal-Télesphore Chiniquy*, which was lithographed in 1848. Le Journal de Québec expressed the wish “that the portrait of M. Chiniquy will grace all the dwellings of the numerous families who should be grateful to this tireless missionary; and there are many of them.” Bernard-Claude Panet*, archbishop of Quebec from 1825 to 1833, Abbé Louis Proulx*, priest of the parish of Notre-Dame de Québec in 1850 and 1851, and Vicar General Antoine Langevin were also painted by Théophile Hamel. This impressive array of ecclesiastics dressed in surplices, capes, and richly embroidered stoles should not make us forget humble churchwardens such as François-Xavier Paradis of the council of Quebec’s Saint-Roch parish; the subtle portrayal of Paradis constitutes a high point in Théophile Hamel’s art. Few other works can match the animation of this face, with its intelligent look, or the gracefulness of the pose. The hands, one of which holds an address of thanks drafted by the parish councillors, contrast with so many inert and expressionless hands given to other persons by Hamel. Nuns seldom appear in his work. The picture of Sister Marie-Rose [Eulalie Durocher*] was painted a few hours before the death of the co-founder of the community of the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary. “When they returned from the cemetery and saw the picture placed at the feet of the Virgin whom the mortal remains of the founder had just left, sisters and pupils cried out together: ‘It is she! It is our Mother! She is going to speak!’” This is one of the most beautiful 19th century pictures of a nun.

The outline of his work clearly shows that Théophile Hamel painted all the most respectable elements in mid 19th century Canadian society. The most prominent politicians and doctors, mayors of Quebec and wives of important persons, had their portraits done by the artist.

A whole section of Théophile Hamel’s work still remains obscure. Almost nothing is known of his religious compositions. Some ten canvases deal with the New Testament: Sainte Geneviève (Notre-Dame-des-Victoires at Quebec), a Pèlerin (1846), a Christ mort (Sisters of Charity of Quebec, 1860), Saint Raphaël (Verchères), Vierge et enfant (1867), Jésus au milieu des docteurs (Saint-Ours), Saint Laurent présentant les pauvres au gouverneur de Rome (Musée du Québec), and La Présentation de Jésus au temple (chapel of the Jesuit fathers at Quebec, 1862; copy of a picture by Louis de Boullongne). The Old Testament was of little interest to him, providing only two subjects: Les Filles de Jethro has disappeared, as has Samson poursuivant les Philistins, a picture for which Charles-René-Léonidas d’Irumberry* de Salaberry is said to have posed. A single religious composition is concerned with contemporary events: Le Typhus (church of Notre-Dame-du-Bon-Secours at Montreal, 1847), which shows the Sisters of Charity looking after the sick. The limitations of the artist show up clearly in these large-scale works.

The arrival of the Desjardins collection in Quebec at the beginning of the 19th century was not an unmixed blessing. Many of the compositions of these European painters were so superior to local products that artists came to prefer copying to creating. Painters such as Joseph Légaré* and Antoine Plamondon adopted the reassuring path of the copyist. Hamel followed suit. It is not surprising that a painter who was associated almost exclusively with one particular type of portrait – a solitary individual, seen full face or three quarters, generally seated – and who refused to paint husbands and wives on the same canvas, should feel at a loss with a subject in which a crowd of individuals had to be arranged. Hamel made several copies. The most famous is Le Repos de la Sainte-Famille pendant la fuite en Égypte, after a picture attributed to one of the Vanloos, which is preserved in the cathedral at Quebec. Hamel’s picture was damaged by fire on 5 May 1866 and replaced by another copy, for which Hamel received 70 louis. From this copy Hamel probably made several replicas, including those in the churches of Saint-Jean-Baptiste at Quebec and Notre-Dame-de-Liesse at Rivière-Ouelle. He is thought to have made several copies of a Descente de croix attributed to Peter Paul Rubens. One must remember that for most people at that period a good copy was worth almost as much as an original.

Théophile Hamel’s range of subjects is narrow. Indeed, his work is essentially portraiture. His few religious compositions, still little known, are largely copies. To this list can be added some drawings, a landscape, and a still life. There are no historical and mythological themes. Should one see here a lack of imagination? Must one conclude that he could not organize large-scale compositions? Answers to these questions will lead to an evaluation of the importance of Théophile Hamel’s artistic production.

A close examination of the portraits of adults painted by Hamel suggests several comments. First, he never ventured to portray two adults on the same canvas. His master Plamondon had taught him how to make a face stand out, with a simple technical handling. Hamel adhered to it all his life. He chose positions presenting the fewest problems. He seated his model, placed himself at the same height, then painted the subject full face or slightly in profile. Although he sometimes avoided the hands of his subjects, he painted them more often than did Plamondon. Before 1843 these hands are unhappily stiff: witness the portraits of M. and Mme Dionne (about 1841), Michel Bilodeau (1842), and his father and mother (1843). After Hamel’s return from Europe, the hands remain heavy although the fingers are flexed to some extent and there is some mobility of the wrist. The portraits of René-Édouard Caron* (1856), Mme Marc-Pascal de Sales Laterrière (1853), and Cécile Bernier (1858) make us forget the primitive character of the hands of the 1840s. The men have an elbow placed on the back of their chair or hold a book, the women have their hands crossed demurely. The unusual pose of Mme Laterrière is in itself surprising. The flowing lines, set off by the grace of the long hands, give this picture a charm and freshness that are rare in Hamel.

Generally, Théophile Hamel’s portraits lack richness of detail. The rather stiff dignity of the personages takes its place. Usually the model stands out against a completely unrelieved background, although sometimes a heavy curtain serves as back-drop. In either case, light is concentrated at the level of the face and this creates a majestic effect which customarily is found in pictures of saints. More infrequently, a window suggests a landscape beyond. The artist even tried to indicate that Mme Charles-Hilaire Têtu and her son were set in a landscape, and were, indeed, outside. But the heavy tasselled hangings, like those in the Jeune fille en rose of Plamondon, and the dull landscape, make the back-drop insipid; we are brought back inside again, rather clumsily. The enormous squat columns that are the chief element of the décor for the portraits of Abbé Louis-Jacques Casault, René-Édouard Caron, and Mme Cyrice Têtu appear scarcely more felicitous. The introduction of a child allowed some modification in the composition. The arrangement is then similar to that of the portrait of a man with his elbow on a chair. Thus the pose of Mme Têtu and her son Eugène resembles that of Charles Wilson. The lack of boldness of these portraits appears evident as soon as they are compared with La Comtesse d’Haussonville of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1845), the portrait of Lavoisier et sa femme (1788) by Louis David, or the Frédéric Villot (1832) of Eugène Delacroix.

Does Hamel show more imagination in the minor details? He avoids difficulties by simplifying to the utmost his handling of delicate lace work (Mme Rolland), women’s hair (Mme Belleau), and even jewellery. We may compare in this respect the portrait of Mme Marcotte de Sainte-Marie by Ingres (1826) with that of Mme Charles-Hilaire Têtu et son fits Eugène. Whereas the long pendant worn by the first woman harmonizes with her eccentric hair style and the neck of her dress to create a lively, almost fanciful work, the simple presentation of the piece of jewellery Mme Têtu leaves forgotten on her lap accentuates the stillness of the composition. The shawl Mme Rolland put on her chair is a pale reflection of the one enveloping the shoulders of Mme Philibert Rivière in Ingres’ painting (1805). A further detail enables us to evaluate this desire for simplification. The lion’s head, a common ornament on the chairs of the period, appears in the pictures portraying Abbé Casault and Sir Allan MacNab. It looks like a rough sketch beside the one painted by Ingres in the portrait of Philibert Rivière. These circumstances help us to understand more readily why Hamel only needed a morning to produce an entire portrait.

The range of feelings expressed in this imposing gallery of personages is restricted. Hamel’s greatest successes are his portraits of men, in which he excels in conveying the importance the models attach to the prestige of their position. Charles Wilson lifts his chin with superb dignity. The powerful torso of Melchior-Alphonse de Salaberry supports an imposing head at once both grave and affable. In the churchmen, a certain gentleness usually tempers the coldness (Abbé Antoine Langevin) or the complacency (Abbé Édouard Faucher) reflected in the eyes. The female faces express a gentle resignation more evocative of nuns than of women anxious to please. Yet the candour of Cécile Bernier, the subtle smile of Mme Dessane, and the slightly worried expectancy of Mme Marc-Pascal de Sales Laterrière show a sensitive grasp of the delicate interplay of feelings in young women who were admired, despite the restraints of their deportment and dress. With very rare exceptions (Mme Georges-Barthélemi Faribault and Mme René-Édouard Caron) all the women Hamel painted wear heavy dresses as discreet as their faces.

The absence of any sensuous element in the majority of Hamel’s feminine models is matched by the rarity of a smile in the children. Gustave et Hermine Hamel (Musée du Québec) pose with a too docile gravity. The babies, such as the infant Jesus the Redeemer, look concerned. The little Léocadie Bilodeau, Ernest Morisset, and Olympe et Flore Chauveau are among his best achievements.

The considerations discussed here make it possible to take a comprehensive view of Théophile Hamel’s production. The severe restraint of the technique gives to most of the artist’s works a solidity further accentuated by a general dark tonality contrasted with some warm tones. His brush scarcely touches his backgrounds. Garments sometimes shimmer, but rarely. It is astonishing, therefore, that Hamel should have been described as “a fanatic for detail.” The backgrounds of some canvases barely have a layer of paint, and he seldom puts paint on thickly. From this point of view, the portrait of Salaberry constitutes a happy exception. On the bullions of the epaulets, on the buttons and the collar, vigorous brush strokes produce a pearly grey sparkle that contrasts effectively with the red of the uniform. More subdued strokes bring out the angle of the epaulets. Rich blacks, browns, and greys, freely used, create surprising effects in juxtaposition with a brilliant garnet-red or crimson.

Théophile Hamel’s real originality is in the faces of his subjects. The variety and delicacy of several of these testify to the artist’s psychological acumen. He concentrated his solid sketching abilities there, with the abundance of commissions certainly one of the reasons. Within the severe framework he imposed on all his models, Hamel succeeded in varying expressions and in bringing out the revealing features.

Hamel did not get this strict economy of means either from the Flemish painters or from the neo-Classics or the French Romantics. Titian was his master as much as if not more than Antoine Plamondon; his letters say so and his works prove it fully for most of his composition exists in Titian. L’Homme au gant in the Louvre may have provided him with his arrangement of a man seated, with an elbow on a piece of furniture and a hand at rest. This arrangement is repeated exactly in the portraits of Charles Wilson, Archibald Campbell, James Stuart*, and Jean-Roch Rolland. The minor details such as windows, landscapes, columns, and curtains are also found in Titian.

Hamel hardly ranks as a painter of religious compositions. Yet he attached enough importance to these pictures to send two of them to the 1867 Paris exposition. Apparently Sainte Geneviève and the Vierge à l’enfant were shown with a self-portrait and the portrait of Salaberry. The heavy treatment of the saint, seated in a bergère before an ill-defined landscape, and the lack of originality with which the Madonna and child are represented, are surprising in an artist who had reached the summit of his career. His other religious compositions must be studied in comparison with the canvases in the Desjardins collection and those of Plamondon. Several are copies, such as Jésus au milieu des docteurs, after Samuel Massé’s picture at Saint-Antoine-de-Tilly, itself a copy of an unknown master.

Several of Théophile Hamel’s works were not executed in the presence of the model. Others were done both with the model and with a daguerrotype. Finally there are the copies. The large-scale religious subjects required much of the artist’s time, and a skill in composition he did not possess. Parish councils were readily satisfied with copies, which had the advantage of being cheaper.

This leads to the question of the sources of Théophile Hamel’s art. Can we find an evolution by starting from his sources? He was helped by several factors. First was the talent of his master Antoine Plamondon, through whom he made contact with the pictures of the Desjardins collection. In addition, certain bold flights of fancy of Plamondon captivated him. We certainly owe to Plamondon’s influence the magnificently successful self-portrait of 1837. The freshness of its landscape, the vigour in each undulation of the foliage, and the ease of the pose were to give place to a more sober approach.

Théophile Hamel’s studio and a great part of his equipment were destroyed by fire in 1862. We possess, however, a series of 24 prints which had belonged to him: studies of mouths and noses, faces, warriors, an Agrippine, and a Saint Bernard. The latter may have inspired his Saint Hugues, painted in 1849. A small girl’s face resembles that of the eldest daughter of Mme Jean-Baptiste Renaud (1853). A study of a male nude perhaps became the insipid central figure of Saint Laurent présentant les pauvres au gouverneur de Rome. All this work is of little value.

His studies in Italy marked him profoundly. Although he admired Rubens, Titian became his real master, and the Italian classical tradition moulded his work more than any other artistic movement.

Three elements constantly recur in his painting. First, dignity: within the limited range of feelings in his many portraits there is always present the considerable nobility that primarily characterizes his art. Second, verisimilitude: contemporary critics never ceased to praise the likeness between his portraits and the models, his most enduring merit. Finally, the very restraint of the technique, which gives most of his works a solidity accentuated by the contrast of dark and warm tones; though the brush seldom lingers to catch reflections and sharp contrasts, his technique, acquired during a long apprenticeship of six years and perfected by copying the great masters, never falters.

Théophile Hamel succeeded in finding a style which suited his temperament and the aspirations of Canadian society in the 1850s. A quiet, steady person, he never felt attracted to venture into complex composition and chromatic brilliance. His training and his desire to live in the upper social strata predisposed him towards an art characterized by nobility. His influence marked the generation that followed. Napoléon Bourassa*, Ludger Ruelland, his nephew Joseph-Arthur-Eugène Hamel*, who all worked in his studio, and Sister Marie de l’Eucharistie, who died in 1946, perpetuated his manner into the 20th century. The study of Théophile Hamel’s work throws light on the art of a whole century.

[The main outlines of Théophile Hamel’s biography were established in Le Courrier du Canada shortly after his death and have come down to us unchanged. The extensive documentary material available in archives now makes it possible to describe the man more closely and to re-evaluate his artistic work. r.v.]

AJQ, Greffe de Philippe Huot, 8 janv. 1867. ANQ-Q, AP, Coll. Bourassa, Boîte 1, lettres de Napoléon Bourassa à Théophile Hamel, 10 mai, 29 juin 1852, 14 déc. 1855, 28 juin 1857, 11 sept. 1861, 13 avril 1864, 7 juin 1868, 12 juin 1869, 24 juill. 1870; État civil, Catholiques, Hôpital Général de Québec, 8 nov. 1817; Notre-Dame-de-Foy (Sainte-Foy, Qué.), 23 nov. 1852, 28 nov. 1855, 5 mai 1859; Notre-Dame de Québec, 2 août 1822, 29 août 1827, 30 mars 1830, 22 sept. 1840, 26 oct. 1842, 31 janv. 1844, 30 août 1860, 24 nov. 1862, 26 sept. 1864, 29 nov. 1865, 23 déc. 1870; Greffe de Joseph Petitclerc, 5 juill. 1834, 27 déc. 1841, 10 juin 1843, 10 juill. 1851, 11 févr. 1854, 11 mars 1856, 8, 23 sept., 8 oct. 1857, 31 août 1858, 20 avril 1861, 24 janv. 1863. Archives de la résidence des Jésuites (Québec), Diariums du supérieur, cahier 1915–16, 130; Procès-verbaux du conseil de la congrégation Notre-Dame de Québec (congrégation des hommes), 1, 192–93, 218; II, 208. Archives paroissiales, Immaculée-Conception (Saint-Ours, Qué.), Livres de comptes, 31 juill. 1831, 4 nov. 1842; Notre-Dame-de Foy (Sainte-Foy, Qué.), Livres de comptes, 1843; Notre Dame de Québec, Livres de comptes et délibérations, 7 mai 1867; Saint-Charles (Saint-Charles-de-Bellechasse, Qué.), Registres de la fabrique, 1856; Saint-Charles-des-Grondines (Grondines, Qué.), Livres de la fabrique, 18 janv. 1846, 23 févr. 1847. Archives paroissiales de Saint-Roch (Québec), Livres de comptes et délibérations, 31 oct. 1862. Archives privées, Anne Bourassa (Montréal), correspondance de Théophile Hamel avec sa famille de 1843 à 1867. Archives privées, Madeleine Hamel (Québec), lettre de Théophile Hamel à Cyrice Têtu, 11 juin 1844; Alphonse Leclerc à Théophile Hamel, 27 avril 1870; livre de comptes de Théophile Hamel. ASQ, C 51, 19 mai 1858; Fonds Casgrain, Lettres, IV; Fonds Viger-Verreau, 38, no. 287, 19 févr. 1847; Journal du séminaire, 24 févr. 1853, 31 déc. 1861, 22 avril 1862, 10 juin 1867, 12 avril 1868, 22, 27 déc. 1876; Plumitif, 21 oct. 1852. Can., prov. du, Assemblée législative, Journaux, 1844, 1853; Conseil législatif, Journaux, 1861. L’Ami de la religion et de la patrie (Québec), 21 avril, 6 oct., 3 nov. 1848. L’Aurore des Canadas, 25 avril 1843; 14 août 1846; 15 juin, 2 nov. 1847; 18 nov. 1848. Le Courrier du Canada, 26 déc. 1870. Daily Colonist (Toronto), 24 Nov. 1856. Le Journal de Québec, 18 avril, 5 oct., 10 juin 1843; 15 sept. 1846; 11 nov. 1848; 16 oct. 1851; 29 janv., 25 juin, 19 nov. 1853; 27 nov. 1856; 30 janv. 1858; 4 déc. 1862; 16 févr., 21 mai 1867; 9 avril 1870; 3 juill. 1889. La Minerve, 16 sept. 1847; 30 mars 1848; 25 juill. 1850; 15 oct. 1853; 31 mars 1860; 22, 24 mars 1865. Morning Chronicle (Quebec), 20 June 1853, 28 July 1858. Quebec Mercury, 27 Oct. 1840. R. H. Hubbard, Antoine Plamondon/1802–1895, Théophile Hamel/1817–1870; two painters of Quebec (Ottawa, 1970), 34, 40, 43. Georges Bellerive, Artistes-peintres canadiens français; les anciens (Québec, 1925), 43–51. William Colgate, Canadian art, its origin & development (Toronto, 1943), 26–38. P.[-J.-B.] Duchaussois, Rose du Canada, mère Marie-Rose, fondatrice de la Congrégation des Sœurs des saints noms de Jésus et de Marie (Montréal, 1932), 287–89. J. R. Harper, La peinture au Canada des origines à nos jours (Québec, 1966), 79, 90–93, 130, 136, 145, 235, 423. Gérard Morisset, Coup d’œil sur les arts en Nouvelle-France (Québec, 1941). P.-V. Chartrand, “Les ruines de Notre-Dame,” Le Terroir (Québec), V (1924–25), 100–3, 126–30, 153–57, 162, 438–39. Hormidas Magnan, “Peintres et sculpteurs du terroir,” Le Terroir (Québec), III (1922–23), 342–54, 410–22.

Cite This Article

Raymond Vézina, “HAMEL, THÉOPHILE (baptized François-Xavier),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 21, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hamel_theophile_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hamel_theophile_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | Raymond Vézina |

| Title of Article: | HAMEL, THÉOPHILE (baptized François-Xavier) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1976 |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | December 21, 2024 |