Source: Link

COOLEY, CHLOE, enslaved Black woman; fl. 1793 in Queenston, Upper Canada.

Chloe Cooley is known because of a single 1793 incident that led to the confirmation of slavery as a legal institution in Upper Canada and set in motion its gradual abolition. Sometime before March 1793, Sergeant Adam Vrooman, a loyalist residing in Queenston, purchased Cooley from Benjamin Hardison, a farmer and merchant in Bertie Township (Fort Erie). She would have been a domestic servant in the Hardison, and then Vrooman, household. Her coerced labour likely included taking care of the children of Vrooman and his wife, Margaret. Cooley would have performed myriad domestic duties, such as cleaning, cooking, laundering, ironing, and making butter, soap, and candles. On the farm she probably tended to livestock, harvested crops, milked cows, and chopped firewood.

On 14 March 1793 Cooley was brutally bound with a rope, thrown into a boat, and taken across the Niagara River to be sold in the United States. Vrooman had enlisted his brother Isaac and a son of fellow loyalist McGregory Van Every to assist him. Cooley tried physically to resist the three men and screamed loudly for help, but her efforts were futile. Nothing is known of what became of Cooley afterwards.

One week later, Peter Martin*, a Black loyalist and army veteran, and William Grisley, a white labourer working for Vrooman, reported the Cooley incident to the Executive Council. The two men had witnessed her struggling and screaming. Grisley testified that Vrooman had told him he intended “to sell his negro wench to some persons in the States.” Three of the five council members – Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe*, Chief Justice William Osgoode*, and senior government official Peter Russell* – were in attendance. Alexander Grant* and James Baby* were absent. The council resolved to prevent any such further breaches of the peace and directed Attorney General John White to prosecute Vrooman. White filed charges against him in the Court of Quarter Sessions at Newark (Niagara-on-the-Lake). On 18 April Vrooman responded in a petition:

Your petitioner has been informed that an information had been lodged against him to the Attorney General relative to his proceedings in his Sale of said Negroe Woman; your Petitioner had received no information concerning the freedom of Slaves in this Province, except a report which prevailed among themselves, and if he has transgressed against the Laws of his Country by disposing of Property (which from the legality of the purchase from Benjamin Hardison) he naturally supposed to be his own, it was done without knowledge of any Law being in force to the contrary.

Vrooman went on to explain that Cooley had previously behaved in an “unruly manner.” He alleged that she had stolen property from him, refused to work on several occasions, and engaged in petit marronnage, fleeing for short periods of time. Her actions, and the whispers circulating among enslavers and enslaved about the possibility of abolition, may well have prompted his decision to sell her to avoid incurring future losses.

He was correct that he had not committed a crime. According to British property law, Cooley and other enslaved Black men, women, and children in the province were considered the chattel of the white settlers who held them in bondage. They were not legal persons, and therefore they did not have any rights to defend in court. Vrooman could do with Cooley as he wished; the charges against him were subsequently dropped.

Simcoe and White promptly used the Cooley incident as the impetus to introduce a law to end slavery in Upper Canada. On 19 June, White proposed an abolition bill in the House of Assembly. It received opposition, because at least 14 members of the government held Black or Indigenous slaves: François Baby*, James Baby, Joshua Booth*, Richard Cartwright*, Richard Duncan*, Alexander Grant, Robert Hamilton*, Ephraim Jones*, William Macomb, John McDonell*, Peter Russell, David William Smith*, Hazelton Spencer*, and Peter Van Alstine.

A compromise was struck and the legislature passed An act to prevent the further introduction of slaves, and to limit the term of contracts for servitude within this province, which received royal assent on 9 July. The Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada, as it became known, did not manumit any enslaved persons. First and foremost, it confirmed and authorized the life-long subjugation of those enslaved at the time of its passage. Secondly, while it prohibited the importation of enslaved persons, it still allowed their sale and purchase within the colony or across the border. Thirdly, the act laid the foundation for gradual abolition: the children of enslaved mothers would be born into bondage but then freed upon reaching 25 years of age. Fourthly, the act outlined the obligations of former enslavers to those they had manumitted, and it encouraged former enslavers to employ freed individuals as indentured servants.

By the 1810s the number of Black people who were enslaved in Upper Canada would decline. Many of those who gained their freedom entered into wage-labour arrangements with their former enslavers or with other settlers. Only a handful of people were still in bondage when the British parliament abolished slavery in most colonies in 1834. Some who had been subjugated were able to transition to living in freedom with considerable success, such as John Baker*.

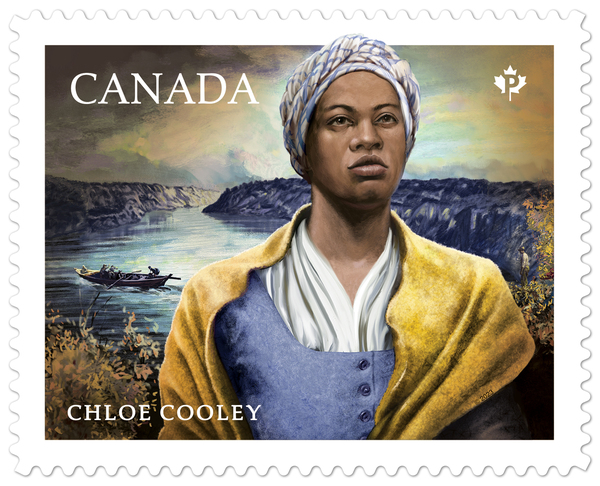

As an enslaved Black woman in Upper Canada, Chloe Cooley did not have any rights. Although not much is known about her except for the description in the Vrooman petition, she left a permanent mark on history. She contested her forced condition and Vroomans’ exertion of control, and her resistance against her enslaver and her circumstances influenced the passage of the law that provided people of African descent with a path to freedom, something that was denied her. In her honour, an Ontario Heritage Trust plaque was erected in Niagara-on-the-Lake in 2007. Fifteen years later the federal government recognized Cooley as a person of national historical significance, and in 2023 she was honoured with a Canada Post commemorative stamp.

Library and Arch. Can. (Ottawa), R10875-4-5 (Executive Council Office of the Province of Upper Canada fonds, land submissions), vol.514, petition 8 (Adam Vrooman, 18 April 1793; copy at www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/microform-digitization/006003-119.01-e.php?q2=29&q3=2646&sqn=1092&tt=1265&PHPSESSID=lb645d1csk2aseg41dmk5na8m0); R10875-18-5 (Executive Council Office of the Province of Upper Canada fonds, …, land and state book A), testimonies of Peter Martin and William Grisley, 21 March 1793 (copy at heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c100, image 947). PAO, F 46 (Peter Russell fonds). Toronto Reference Library, Special Coll. & Rare Books, L 21 (Elizabeth Russell papers). Upper Canada Gazette (Toronto), 19 Aug. 1795; 20 Dec. 1800; 18 Jan 1802; 2 Sept. 1803; 15, 19 Feb. 1806. The correspondence of the Honourable Peter Russell: with allied documents relating to his administration of the government of Upper Canada during the official term of Lieut.-Governor J. G. Simcoe, while on leave of absence, ed. E. A. Cruikshank and A. F. Hunter (3v., Toronto, 1932–36). Natasha Henry-Dixon, “One too many: the enslavement of Black people in Upper Canada, 1760–1834” (phd thesis, York Univ., Toronto, 2023). J. K. Johnson, Becoming prominent: regional leadership in Upper Canada, 1791–1841 (Kingston, Ont., and Montreal, 1989). C. A. Nelson, Slavery, geography and empire in nineteenth-century marine landscapes of Montreal and Jamaica (London and Montreal, 2016). The statutes of the province of Upper Canada … (Kingston, 1831).

Cite This Article

Natasha Henry-Dixon, “COOLEY, CHLOE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 13, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cooley_chloe_4E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cooley_chloe_4E.html |

| Author of Article: | Natasha Henry-Dixon |

| Title of Article: | COOLEY, CHLOE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2025 |

| Access Date: | April 13, 2025 |