Source: Link

BAKER, JOHN (baptized John Gray), enslaved Black man, labourer, and soldier; b. in the early 1780s in Quebec, son of Dorinda (Dorine); d. 17 Jan. 1871 in Cornwall, Ont., and was buried there in the cemetery of Trinity Anglican Church.

John Gray was born into slavery in Quebec on a Christmas Day in the early 1780s. The surname Gray, which appears on his 1786 baptismal record, was that of his enslaver. He was the son of an enslaved Black woman, Dorinda, and a white man whose identity is unknown. (In his old age, John would recall only that his father “was a Dutchman.”) When John was very young, his mother married a German settler, Jacob Baker, and at some point John adopted his stepfather’s surname.

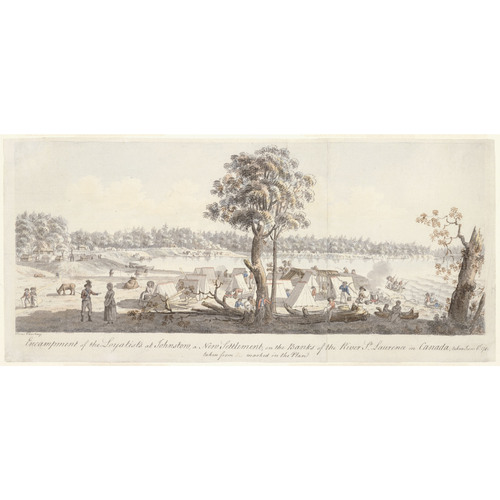

According to the law and the practice of racial chattel slavery, children of enslaved Black women inherited the status of their mother. John, his mother, and his elder brother, Simon, were enslaved by Major James Gray and his wife, Elizabeth. Following the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War in 1775, during which Major Gray would serve in the King’s Royal Regiment of New York [see Sir John Johnson*], he and his family relocated to Quebec. Like many other loyalists who migrated northwards, the Grays brought with them the Black people they had enslaved in the Thirteen Colonies.

In 1792 Major Gray was appointed lieutenant of Stormont County, at the eastern end of the recently created province of Upper Canada. The Grays resided in New Johnstown (Cornwall) on a 1,200-acre estate, where they held Dorinda and her children in bondage. When Major Gray died in 1795, they became the property of his only son, Robert Isaac Dey Gray*, Upper Canada’s first solicitor general. Those whom he enslaved would eventually include not only Dorinda, John, and Simon, but also the six children Dorinda had with Jacob Baker.

Servitude to the Gray family

As an enslaved child, John would have worked from a young age, performing chores such as feeding farm animals and gathering firewood. He also would have helped his mother and their enslaver Elizabeth Gray to collect and prepare food, clean the residence, harvest vegetables and fruits from the kitchen garden, spin wool into yarn, make candles, sew clothing and blankets, and cut wood. When they were older, John and Simon also laboured as personal servants to both Major Gray and his son, Robert.

John and Simon were severely punished by Major Gray. John would later recall: “He was strict and sharp; he made us wear deer skin shirts and deer skin jackets, and he gave us many a flogging. At these times he would pull off my jacket and the rawhide would fly around my shoulders very fast.” Because the two brothers were considered to be, in legal terms, Gray’s property rather than the children of their mother, there was no recourse for the physical violence they endured.

Both John and Simon moved to York (Toronto) with Solicitor General Gray when he relocated to the new capital city sometime after the approval of his appointment in the colonial government in May 1795. There John performed many chores for his enslaver, such as cleaning, washing clothes, running his bath, and shaving him; he also looked after Gray’s horses, making sure they were well groomed and fed. As his enslaver’s personal attendant, John accompanied him on business trips, carrying baggage and assisting in any other way he was needed. Before leaving York, he had also performed these duties for Elizabeth Gray’s nephew, Jacob Farrand; John was likely hired out for this purpose.

Manumission and military career

On the night of 7–8 Oct. 1804, Solicitor General Gray and Simon drowned when the schooner Speedy sank with all hands during a gale on Lake Ontario. In his will Gray had ordered that Dorinda and her children be freed from bondage. John was given 200 acres of land (lot 17 of the second concession of Whitby Township) and £50. Dorinda was bequeathed a trust fund of £1,200. Simon, had he lived, would have been awarded 200 acres of land (lot 11 in the first concession of Whitby Township), a £50 gift, clothes, and a silver watch. Many years afterwards John would state, “We got a little of the money he left for us, but not much.”

John Baker was a free man. Of this period in his life he later recounted: “There were about twenty houses in Toronto then. I went and stayed at Judge Powel’s [likely the home of William Dummer Powell*] for six months.” Baker then enlisted in the British army’s New Brunswick Fencibles [see Sir Martin Hunter*], which was recruiting in York, and he left for New Brunswick to train and begin his service. Within this regiment, known from 1810 as the 104th Foot, there was a pioneer unit composed entirely of Black soldiers. These men, about ten in number, performed various skilled construction tasks, such as clearing and building roads, erecting bridges, and repairing entrenchments and fortifications.

When the War of 1812 erupted, the 104th was called to help defend Upper Canada. During the winter of 1812–13, Private Baker and his regiment made the difficult 52-day, 700-mile overland journey from Fredericton to Kingston, Upper Canada, to help defend the St Lawrence River against American attacks. That winter was harsh with heavy snowfall, and several accounts report that the men suffered dreadfully during the trip. On 19 May 1813 the unit raided Sackets Harbor, N.Y., to weaken the American navy squadron stationed there. After garrisoning in Kingston for 14 months, several companies of the 104th, including Baker’s, went on to the Niagara frontier, where they participated in the battle of Lundy’s Lane [see Sir Gordon Drummond*] on 15 July and the siege of Fort Erie in August and September.

Baker was wounded in battle – it is not clear whether at Sackets Harbor or Lundy’s Lane – but he recovered and stayed on active duty. After the War of 1812 ended in North America, he went overseas with another regiment of the British army and fought in the battle of Waterloo (Belgium) on 18 June 1815. Many years later he claimed: “I saw Napoleon. He was a chunky little fellow; he rode hard and jumped ditches.” Baker liked serving in the military. In 1868, by which time he was quite elderly, he mused, “If I were young and supple I would not be out of the army.”

Remaining years in Cornwall

After he was discharged, Baker returned to Cornwall and reunited with his mother and stepfather and his half-siblings, Lovina, Margaret, Jane, Bridget Glennie, Elizabeth, and Jacob. At some point Baker married a woman named Hannah. He worked as a general labourer, which included doing odd jobs for a local business owner. According to author Jacob Farrand Pringle, “For the last few years of his life he was to be seen daily, limping down to the store of the late P. E. Adams, on Pitt Street, and in the interval took a seat in one particular part of the store, where it is said that the floor was worn away in the place where his feet rested.” Baker enjoyed woodcarving as a hobby in his old age. He had to wait until 1861 to finally receive his war pension, after which he was paid one shilling sterling per day by the British government until his death.

In 1867 Baker performed his civic duty as a witness in the case Morris v. Henderson, which was heard in Ottawa’s assize court. He was asked to testify that two people relevant to the lawsuit had died many years earlier. His appearance was covered in the Ottawa Times, which described him as “perhaps the last surviving Canadian slave” and discussed his experiences in bondage and during the War of 1812. The following year the Toronto lawyer James Cleland Hamilton interviewed him for an article published in that city’s Telegraph on 15 Dec. 1869. In it Baker recalls details of his life, including his birth in Quebec, his family genealogy, his forced labour for the Grays and the punishment he suffered at their hands, the deaths of Simon and Solicitor General Gray, his manumission, and his military service. This interview is one of only two known first-hand accounts of Black people who were enslaved as children in Upper Canada. (The other is that of Sophia Burthen (Pooley), who was enslaved by Joseph Brant [Thayendanegea*] and his wife Catharine [Ohtowaˀkéhson*]).

After a long life John Baker died on 17 Jan. 1871. He is buried in the cemetery of Trinity Anglican Church in Cornwall. Baker’s personal journey was atypical for a Black person enslaved in Upper Canada. It had taken him from racial chattel slavery to freedom, from servant to soldier, and from veteran to community elder.

Arch. of Ont. (Toronto), F 978 (Church records coll.), Williamstown – St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, Reg. of baptisms and marriages, 1779–1810, John Gray, 8 May 1786 (copy at heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c3030, image 343); RG 22-155-0-696 (Gray, Robert I. D., estate file, 19 March 1804; copy at www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSDM-JQJM-P?cat=218510&i=222). Library and Arch. Can. (Ottawa), R233-30-3, vols.49–157, Can. West (Ont.), dist. Stormont (county) (36), subdist. Cornwall (350): 53. Freeholder (Cornwall, Ont.), 11 Nov. 1851. Ottawa Times, 2 May 1867. Toronto Telegraph, 15 Dec. 1869. Patrick Campbell, Travels in the interior inhabited part of North America in the years 1791 and 1792 … (Edinburgh, 1793). J. C. Hamilton, “The African in Canada,” American Assoc. for the Advancement of Science, Proc. (Philadelphia), 38 (1890): 364–70; “The Maroons of Jamaica and Nova Scotia,” Canadian Instit., Proc. (Toronto), new ser., 7 (1890): 260–69; Osgoode Hall: reminiscences of the bench and bar (Toronto, 1904). Natasha Henry-Dixon, “One too many: the enslavement of Black people in Upper Canada, 1760–1834” (phd thesis, York Univ., Toronto, 2023). J. F. Pringle, Lunenburgh or the old Eastern District, its settlement and early progress, with personal recollections of the town of Cornwall, from 1824 … (Cornwall, 1890; repr. Belleville, Ont., 1972). “Mapping the march of the 104th (New Brunswick) Regiment of Foot,” prepared by W. E. Campbell for the St John River Soc. (Saint John, 2011; copy at DCB). Merry hearts make light days: the War of 1812 journal of Lieutenant John Le Couteur, 104th Foot, ed. D. E. Graves (Ottawa, 1993). W. A. Squires, The 104th Regiment of Foot (the New Brunswick Regiment), 1803–1817 (Fredericton, 1962). J. L. Summers and René Chartrand, “The 104th (New Brunswick) Regiment of Foot, 1803–1817,” in their Military uniforms in Canada, 1665–1970 (Ottawa, 1981), 63–64.

Cite This Article

Natasha Henry-Dixon, “BAKER, JOHN (baptized John Gray),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 21, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/baker_john_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/baker_john_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | Natasha Henry-Dixon |

| Title of Article: | BAKER, JOHN (baptized John Gray) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2025 |

| Access Date: | April 21, 2025 |