Source: Link

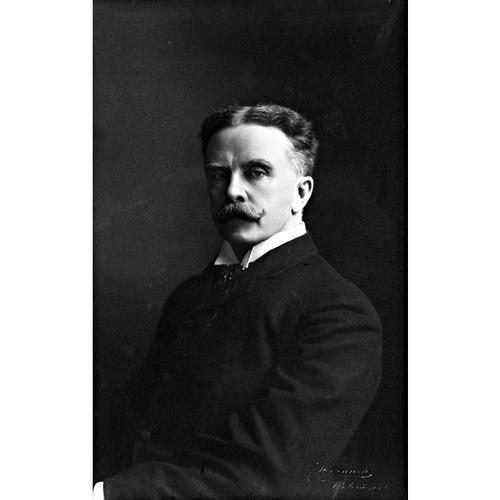

YOUNG, HENRY ESSON, physician, politician, civil servant, and university teacher; b. 24 Feb. 1862 in English River (Riverfield), Lower Canada, son of Alexander Young, a Presbyterian minister, and Ellen McBain; m. first 2 Oct. 1890 Kate Linda Isaacs in London, England, and they had one son; m. secondly 15 March 1904 Rosalind Watson* in Victoria, and they had three daughters and one son; d. there 24 Oct. 1939.

Henry Esson Young was educated at Queen’s College (ba, 1883) in Kingston, Ont. After earning his medical degree at McGill University (mdcm, 1888) in Montreal, he worked under William Osler* at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. He undertook postgraduate studies at London and Guy’s hospitals in England, where he married and had a son with Kate Linda Isaacs. After 18 months in the United Kingdom, he proceeded alone to Chicago and then to St Louis, Mo., for training in eye, ear, nose, and throat conditions. His relationship with Kate and their son appears to have ended there, although no record of divorce has been found; she is listed as a widow in the 1901 England census, and Henry is listed as a bachelor on his subsequent marriage record in Canada three years later.

Family connections and the lure of the gold rush are probably what brought Young to Atlin, in northern British Columbia, around the turn of the century. His brother Frederick McBain Young had moved to the province in the 1890s and would be appointed county court judge for Atlin in 1905. Photographs from this period show Young and male friends on northern hunting trips; among them is a graphic image of a prospector’s frostbitten hands and feet, which were apparently saved thanks to Young’s medical skills. Various issues of the Atlin Claim report that the doctor prospected for gold, involved himself in the local board of trade, negotiated with mine owners regarding the hiring of Japanese labourers, set a broken limb, and sat on a coroner’s jury. He also served as president of the town’s hockey club, vice-president of its gun club, a hoseman in its fire brigade, and a member of its masonic lodge. This eclectic mix of professional, personal, social, and community interests would characterize Young’s entire life. Around 1901 he met his future wife, Rosalind Watson, a gold-medal scholar at McGill who was originally from Huntingdon, Que., while she was doing her ma research in British Columbia’s Cariboo district. She was a teacher with a similarly impressive academic background who would co-author with Maria Lawson A history and geography of British Columbia (Toronto, 1906).

Nominated by the local association of British Columbia’s Conservative Party, Young won the Atlin seat in the provincial general election of 1903 by a vote of 236 to 202 and served in the government led by Richard McBride*. After his re-election in 1907, Young was sworn in on 27 February as provincial secretary and minister of education (the two posts were combined until 1924). He was re-elected in 1909 and acclaimed in 1912. His educational responsibilities, along with the diverse health, social, and cultural aspects of the provincial secretary’s portfolio, meant that Young was in a position to make a significant impact on British Columbia. His ministerial initiatives, and the fact that in 1914 he was the only member of his party to support a women’s suffrage bill, which ultimately failed, marked him as a reformer in his party.

One of Young’s first legislative initiatives was a 1908 act establishing the University of British Columbia (UBC), which would open in Vancouver in 1915. Young worked to improve education in grade and high schools, believing that a broad public curriculum would facilitate both professional and vocational careers and mould good citizens. Acting on advice from the British Columbia School Trustees Association, in 1908 Young made textbooks free in public schools. In 1911 he established the provincial School Magazine (Victoria), with the goal of simultaneously promoting patriotic thought and educational efficiency, and he introduced domestic science as a subject at the Provincial Normal School in Vancouver. These were the first in a series of educational innovations that included night schools, rural science courses, school gardens, and training in domestic science and vocational music. In 1915 a second provincial normal school opened in Victoria.

As part of his work as provincial secretary, in 1908 Young rationalized British Columbia’s civil service, which had previously grown in an arbitrary manner, putting in place a system of grading and salary scales. Three years later he introduced a bill that allowed for the more effective collection of vital statistics, transferring responsibility from the attorney general to the Provincial Board of Health. He also helped the fledgling provincial museum by supporting ethnographer Charles Frederic Newcombe*’s important field work throughout the province, starting in 1911, to augment the institution’s modest collection of Indigenous art and artifacts, and by shepherding into law a bill giving the museum formal operating authority and defining its mandate in 1913. Similarly, his backing of legislative library employee Alma Marjorie Russell’s early efforts to acquire documents and books related to the history of British Columbia contributed to the collection of the Provincial Archives, which had been created in 1908 [see R. Edward Gosnell], while his support of botanist John Davidson* would lead to the establishment of the UBC Botanical Garden in 1916. Under his tenure a new Mental Hospital and Colony Farm had opened in Coquitlam in 1913. The grounds on which it was established were named Essondale in his honour, and the hospital also came to be known by that name. Although it would be rededicated as the Riverview Hospital in 1965, the area around it would continue to be known as Essondale.

Young’s dynamic career as a legislator was cut short in 1915 because of accusations that he had allowed John Arbuthnot, president of Pacific Coast Coal Mines Limited, to hold shares worth $105,000 for him in exchange for lobbying done by Young when the company was negotiating with the provincial government in 1911. Clearly a liability to the Conservative government, Young left the cabinet when it was reorganized in December 1915. That same month he appeared in court as a defendant in the case Pacific Coast Coal Mines, Limited v. Arbuthnot. Young maintained that the shares had been held in trust for him, and that he had never given political or personal favours to his long-time friend Arbuthnot. The case made it all the way to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London, which in August 1917 ordered that the debentures in the company held by Young and the other defendants be cancelled. By that time the affair had essentially finished Young’s political career, and he did not run as a candidate in the 1916 provincial election.

At the end of May 1916, following a stint chairing the British Columbia Returned Soldiers Aid Commission, Young was appointed secretary of the Provincial Board of Health (also known as the provincial health officer). He remained at the post for the rest of his life, and his work in that capacity was substantial. Public and political sentiment following the First World War favoured health and social reform, and he was able to win the support of the provincial Liberal government, the federal Union government [see Sir Robert Laird Borden], the province’s Women’s Institutes, and several philanthropic organizations, to set in place the rudiments of a public-health program. He is credited with the establishment in 1919 of a public-health nursing program at UBC – the first of its kind in the British empire – with initial funding provided by the Canadian Red Cross Society and later by the Rockefeller Foundation. The program trained the first professionals of the province’s growing public-health bureaucracy. Young would teach classes at UBC in both public nursing and social work. Free venereal-disease clinics were established in 1919 in Vancouver and Victoria. In 1921 the province purchased the Tranquille Sanatorium, northwest of Kamloops, from the British Columbia Anti-Tuberculosis Society, making it a base for a travelling diagnostic clinic. The position of provincial epidemiologist was created in 1929, and two years later a provincial laboratory opened in Vancouver.

To serve rural areas, professionally staffed health centres had been set up in the 1920s in Saanich, the Cowichan valley, and Kelowna, most often through a shared funding arrangement that Young brokered between the province and the Rockefeller Foundation. These centres conducted school medical inspections, provided well-baby clinics, and offered dental care and bedside nursing, blending public-health professionalism with maternal feminism. Strongly supported by the province’s Women’s Institutes and closely connected to them, Young relied on their members to staff clinics at the health centres, supply refreshments, and, in some cases, assist with rudimentary medical procedures.

The establishment of the North Vancouver Health Unit in 1930 marked a shift to medical expertise in community health care, heralding the developments of the next decade. In 1933 Thomas Dufferin Pattullo*, a reformist Liberal, led his party to victory and appointed his strongest cabinet ally, UBC education professor George Moir Weir, as provincial secretary. He was welcomed by Young as an individual who understood public health and encouraged those in the provincial bureaucracy to envision a promising future in the field. Internationalists themselves, Weir and Pattullo would also have been impressed by the leadership roles Young undertook in national and international organizations such as the Canadian Public Health Association, the Canadian National Committee for Mental Hygiene, the American Public Health Association, and the American Child Hygiene Association, among many others.

The provincial public-health system that Young created under Weir reflects a shared belief in the activist state, run by experts whose role was to provide individuals with the education and services necessary to become healthy, productive citizens. Visionary men such as public-health specialist Gregoire Fere Amyot, social scientist Harry Morris Cassidy*, statistician John Thornton Marshall, research scientist Claude Ernest Dolman*, and venereologist Donald H. Williams were drawn to developments and opportunities in the western province. They became part of a team of provincial bureaucrats that Cassidy would describe in 1945 as “probably unsurpassed in Canada and that would be distinguished in most states of the American union.” Some, like Marshall, were closely mentored by Young.

Women were not as involved in policymaking under the system that Young helped to develop in the 1930s. The province’s Women’s Institutes, while they remained important supporters of the new programs and conduits to rural populations, were no longer key players in determining priorities and service delivery. Female social workers and nurses, including Young’s daughter Fyvie, who worked at the Cowichan health centre and taught public health at UBC during the 1930s, fulfilled major roles on the front lines but were not represented in policy formation and higher administrative circles.

The larger public-health plan advanced by Young and his colleagues was a system of local health units staffed by full-time trained personnel who were responsible for public education, school health, immunization, and prenatal and post-natal care; they were also charged with identifying cases needing specialized treatment and directing them towards it. Two new health units were established in the Peace River district and the Abbotsford area in 1935, and the Metropolitan Health Board was set up the following year to serve the municipalities of the greater Vancouver area. The Rockefeller Foundation and the Provincial Board of Health dangled the all-important financial carrot in front of municipal governments that were loath to spend money on public-health programs during financial hard times.

In the late 1930s Young created a series of provincial divisions (Tuberculosis Control, Venereal Disease Control, Provincial Laboratories, and Vital Statistics) that employed a model of centralized administrative oversight, laboratory and statistical research, and careful coordination of social work and public-health efforts in the field. Work related to tuberculosis and venereal disease, for example, was conducted in travelling or local clinics and managed from Vancouver headquarters. New patient record systems charted known cases and allowed data to be compiled for research purposes. Public-health nurses, rural field agents, and urban social workers were on the front line teaching hygiene, counselling patients and families, and helping to ensure treatment compliance. During the depression years, when the federal government and most other provinces substantially trimmed public-health budgets, British Columbia under Young was a noteworthy exception.

Young had been awarded honorary llds from the University of Toronto (1907), McGill (1911), and the institution he established as a minister, UBC (1925), from which all his children from his second marriage would graduate. He was a Presbyterian and a member of Victoria’s Union and Pacific clubs, the Royal Victoria Yacht Club, the University Club of Vancouver, and the Arctic Club of Seattle, Wash.

Young died of heart problems in 1939 after a colourful and varied career. In his roles as minister responsible for education, health, and welfare, and later as provincial health officer, he was central to the development of British Columbia’s public-health policy and programs for much of the first half of the 20th century, and was pivotal in many developments in education, particularly the establishment of the University of British Columbia. The trajectory of his intertwined careers as minister and civil servant parallels the early rise of the province’s health and social-welfare infrastructure, and what might be called the zenith of preventive public health in North America and Europe. The provincial budget for health and welfare grew from approximately $100,000 at the turn of the century to about $3.8 million at the beginning of the 1930s. “Prevention,” Young emphatically stated in his Provincial Board of Health report for 1935, “must be the key-note of all public-health work if we are to obtain results satisfactory to the terms humanitarian and economic.” Young’s achievements help us appreciate that early, regional activist state projects – supported in British Columbia’s case by maternal feminist activism and corporate philanthropic funding – provided scaffolding for a more extensive state apparatus later on.

Ancestry.com, “1901 England census,” Abraham Young; “England & Wales, civil registration birth index, 1837–1915,” Abraham Harry Young; “London, England, Church of England marriages and banns, 1754–1932,” Henry Esson Young and Kate Linda Isaacs, 2 Oct. 1890; “Quebec, Canada, vital and church records (Drouin collection), 1621–1968,” Valleyfield, Que., 1862: ancestry.ca (consulted 8 April 2021). BCA, GR-2951, no.1939-09-562475; GR-2962, no.1904-09-012002; PR-0002. Atlin Claim (Atlin, B.C.), 1901–3. Vancouver Sun, 24 Oct. 1939. B.C., Provincial Board of Health, Annual report, 1907–39. Canadian annual rev., 1907–8, 1912–16. H. M. Cassidy, Public health and welfare reorganization: the postwar problem in the Canadian provinces (Toronto, 1945). Peter Corley-Smith, White bears and other curiosities: the first 100 years of the Royal British Columbia Museum (Victoria, 1989). M. J. Davies, “Competent professionals and modern methods: state medicine in British Columbia during the 1930s,” Bull. of the Hist. of Medicine (Baltimore, Md), 76 (2002): 56–83. The development of public health in Canada …, [ed. R. D. Defries] (Toronto, 1940). Electoral history of British Columbia, 1871–1986 ([Victoria, 1988]). The federal and provincial health services in Canada, [ed. R. D. Defries] (2nd ed., [Toronto], 1962). Elizabeth Forbes, Wild roses at their feet: pioneer women of Vancouver Island ([Victoria], 1971). Peter Grant, “Rosalind Watson and Henry Esson Young, part 2: families, schools, professions, marriage, children,” in Oak Bay Chronicles: oakbaychronicles.ca/?page_id=600 (consulted 8 April 2021). “Henry Esson Young,” Canadian Welfare Summary (Ottawa), 15 (1939): 5. E. O. S. Scholefield and F. W. Howay, British Columbia from the earliest times to the present (4v., Vancouver, 1914). G. M. Weir, “B.C.’s progress in health and welfare,” Child and Family Welfare (Ottawa), 12 (1937), no.5: 52–54. Alexandra Zacharias, “British Columbia Women’s Institute in the early years: time to remember,” in In her own right: selected essays on women’s history in B.C., ed. Barbara Latham and Cathy Kess (Victoria, 1980), 55–78.

Cite This Article

Megan J. Davies, “YOUNG, HENRY ESSON,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 20, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/young_henry_esson_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/young_henry_esson_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Megan J. Davies |

| Title of Article: | YOUNG, HENRY ESSON |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2024 |

| Access Date: | January 20, 2025 |