Source: Link

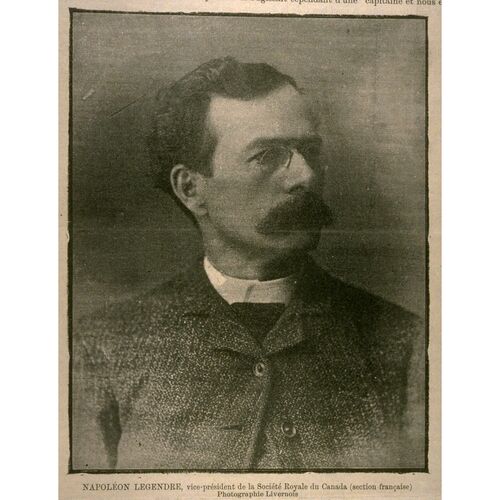

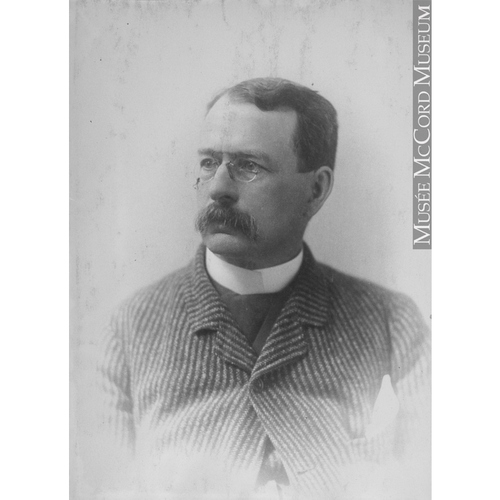

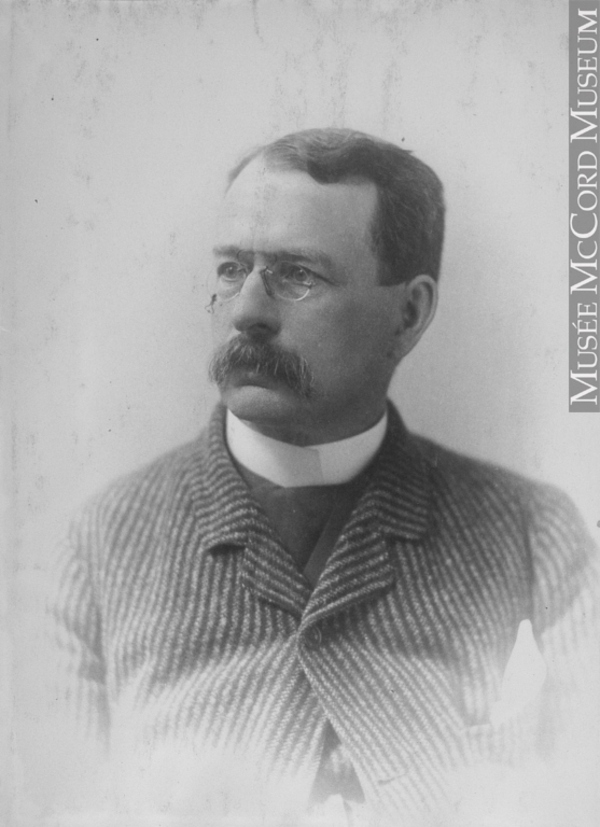

LEGENDRE, NAPOLÉON (baptized Gabriel-Narcisse-Napoléon), lawyer, journalist, writer, and office holder; b. 13 Feb. 1841 in Nicolet, Lower Canada, son of François-Félix Legendre, a farmer, and Marie-Reine Turcotte; m. 7 Oct. 1867 Marie-Louise St-George Dupré at Quebec, and they had one son and three daughters; d. there 16 Dec. 1907.

After primary education with the Frères de la Doctrine Chrétienne at Lévis, Lower Canada, Napoléon Legendre began his classical studies in 1856 at the Collège Sainte-Marie in Montreal. Called to the bar on 5 Jan. 1865, he practised law for some time in Lévis. “But,” writes Camille Roy*, “because of his quiet nature and taste for the inner life, Monsieur Legendre did no more than pass briefly through the bar. Pettifoggery did not appeal to him and clients left him alone.” He much preferred journalism and the pleasures of literature to working at his profession.

Legendre began contributing to the Quebec paper L’Événement in 1867, after his marriage, and continued to do so sporadically until the turn of the century, when illness forced him to terminate his collaboration. Articles he wrote also appeared in Le Pays (Montréal) in 1864 and Le Courrier du Canada (Québec) in 1870–71. On 24 March 1871 the latter paper published one of his first lectures, “La mission du journaliste en Canada,” which had been given before the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec; this lecture was reprinted in Échos de Québec in 1877, along with other pieces he had written for L’Opinion publique (Montréal) in 1875–76, most often under the heading “Chronique de Québec.” In Album de la Minerve (Montréal), Legendre published three long stories and an otherwise unpublished first novel, “Sabre et scalpel,” a Gothic piece in a style made popular by Eugène Sue and Pierre-Alexis Ponson Du Terrail in France and François-Réal Angers*, Joseph Doutre*, and Eugène L’Écuyer in Canada. Set partly in a bandits’ lair at Cap-Rouge, the novel does not appear to have been acclaimed. In Choses et autres Narcisse-Henri-Édouard Faucher* de Saint-Maurice criticized its exotic character and numerous improbable sequences, although he thought some descriptive passages were well done.

In 1873 Legendre succeeded André-Napoléon Montpetit as editor of the Journal de l’Instruction publique (Québec et Montréal). His writing for it included a series of moralistic stories, which came out at Quebec in 1875 in his collection À mes enfants. He left the editorship of the journal in 1875 and the following year became the French-language recorder of the Legislative Council at Quebec. His duties with that body did not prevent him from contributing to L’Opinion publique and other periodicals, including Le Foyer domestique (1877) and L’Album des familles (1880–82), both of Ottawa; La Nouvelle-France (1881), Les Nouvelles Soirées canadiennes (1882–87), Le Canada français (the predecessor of the Bulletin du parler français au Canada, the organ of the Société du Parler Français au Canada, of which Legendre was a founding member) (1888–90), and Le Soleil (1897–98), all published at Quebec; La Presse (1885–90), La Revue des deux Frances (1897–98), and Le Monde illustré (1897–98), all of Montreal; and Le Moniteur de Lévis (1893–95).

Most of the articles Legendre wrote before 1877 were collected in two volumes under the title Échos de Québec. These varied anthologies comprise short news items (“L’encan” and other pieces), sketches and portraits (notably “À travers les rues”), columns (“Les travers de la société”), and more substantial texts consisting of talks and lectures in which he reviewed the history of the press in French Canada. He subsequently returned to the subject of the evolution of writing in French Canada, publishing studies in the Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada, of which he became a charter-member in 1882. He saw French Canadian letters as standing apart from the main body of French literature and he took every opportunity to encourage its development. It is by its literature and arts, he maintained, that “the civilization and greatness of a people are judged.” He came out openly for realism in writing, and readily acknowledged the importance of commerce and industry “in creating the wealth and well-being of a nation.” But his query, “Does not a single book do more to distinguish a people to the outside observer than the most astute commercial and industrial transactions?” reveals his ultimate judgement.

Some 50 of Legendre’s articles and columns on a wide variety of subjects were published simultaneously in the two Quebec papers L’Électeur and La Justice between 1888 and 1890 under the heading “Entre nous.” In them he wrote about Nicolet, misery, vanity, and much else. He also commented on a number of writers and their works, on matters of history, songs, and music, which had always fascinated him since he was a good musician with an excellent voice. He occasionally served as a critic of Quebec City concerts for several periodicals and was even the secretary (1863) and then vice-president (1864) of the Montreal Philharmonic Society. In his article “L’art et les artistes au Canada,” which appeared in the Revue de Montréal in 1878, he emphasized the major role the press could play in the arts in general, insisting that at least a daily or weekly column be dedicated to music. In his view there was no lack of artistic talent in Canada but rather too little public and official encouragement. He called for government involvement to support the arts and artists.

Another expression of Legendre’s passion for music was a solidly documented biography of a French Canadian singer he admired, Louise-Cécile-Emma Lajeunesse*, who had achieved fame on the world’s great stages under the name Emma Albani. The book came out in 1874. Legendre also wrote several articles on singing in the schools and the teaching of solfège.

In 1886 a collection containing 48 of Legendre’s poems, many of which had already appeared in periodicals, was published at Quebec under the title Les perce-neige: premières poésies. He was one of the poets who helped popularize the widespread 19th-century practice of publishing a poem called “Étrennes du Jour de l’An” to mark the arrival of the new year.

The year 1890 was an especially good one for Legendre. In February the Université Laval awarded him an honorary doctorate of letters. Then in the pages of Le Canada français he published a second novel, “Annibal,” which met with more success than his first one and established his affinity with Quebec’s agriculturalist writers. In Nos écoles, a booklet issued that year at Quebec, Legendre examined Quebec’s educational system, from primary and secondary to higher levels, adult education, and normal schools. He called for “banishing rote methods and establishing new and practical approaches.” In his view “the progress of a people depends in large part on the quality of its schools.” An important step towards promoting such progress would be “to improve the position of teachers . . . so that they will commit themselves to their profession and dedicate their time and all their attention to it.” Hygiene, manners, deportment, and dress were points to be stressed in the education of children.

Legendre also concerned himself with the French language and its status in society and education. A collection of his writings on this subject, which had appeared mostly in the Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada, L’Électeur, La Justice, and Les Nouvelles Soirées canadiennes, was published in 1890 as La langue française au Canada. He proudly highlighted the contributions of French Canadians to the enrichment of the French language worldwide, providing a list of expressions and terms for which he claimed what he called “a right of nationality.” These texts show that Legendre had a good knowledge of philology and etymology and that he was a zealous proponent of the French language as spoken in Canada. He held that Canadian French was neither a jargon nor a dialect but true French as spoken in France in the 18th century.

Legendre published another pamphlet at Quebec in 1890, Nos asiles d’aliénés, about private mental hospitals. After reviewing what was being done in other countries, notably France, he concentrated on the lot of patients and the role of staff in these institutions. Mélanges; prose et vers appeared at Quebec in 1891. It contained five romantic poems and two stories, all previously printed in periodicals, as well as “Annibal,” which would also be brought out as a separate volume in 1898. In Montreal in 1878 he had published a pamphlet entitled Notre constitution et nos institutions, in which he explained the role of the assembly, the Executive Council, the lieutenant governor, and the Legislative Council, the powers of such institutions as municipalities, tribunals, and courts of justice, and the functions of recorders, coroners, and fire marshals.

When Napoléon Legendre died on 16 Dec. 1907, columnists noted the passing of one of Canada’s most esteemed and best-known literary figures, who had made his mark “in brief, lively articles on current topics, light narratives, and short stories.” His articles had gained him admission to the Cercle des Dix at Quebec, alongside such other noted journalists and literary figures as Paul de Cazes, Nazaire Levasseur*, and Faucher de Saint-Maurice.

A list of works by Napoléon Legendre appears in DOLQ, 1: 831–32.

AC, Québec, État civil, Catholiques, Notre-Dame de Québec, 19 déc. 1907. ANQ-MBF, CE1-13, 13 févr. 1841. ANQ-Q, CE1-97, 7 oct. 1867. AUL, U-503/31/1, procès-verbaux du conseil, 3 févr. 1890. Charles Ameau, “Napoléon Legendre,” Le Monde illustré (Montréal), 10 août 1889: 117. Le Canada, 17 déc. 1907: 8. Le Devoir, 28 févr. 1910: 8. L’Événement, 17, 19, 26 déc. 1907. Le Journal de Françoise (Montréal), 4 janv. 1908: 296. Camille Roy, “Napoléon Legendre,” L’Action sociale catholique (Québec), 23 déc. 1907: 4. Le Soleil, 17 déc. 1907: 10. Aurélien Boivin, Le conte littéraire québécois au XIXe siècle; essai de bibliographie critique et analytique (Montréal, 1975), 236–41. “Les disparus,” BRH, 35 (1929): 537. DOLQ, 1: 13–14, 33–34, 433, 477. N.-H.-É. Faucher de Saint-Maurice, Choses et autres; études et conférences (Montréal, 1874). D. M. Hayne et Marcel Tirol, Bibliographie critique du roman canadien français, 1837–1900 ([Québec et Toronto], 1968), 98–99. [L.-A. Huguet-Latour], Annuaire de Ville-Marie, origine, utilité et progrès des institutions catholiques de Montréal . . . (2v., Montréal, 1863–82). Gabrielle Patry, “Napoléon Legendre, 1841–1907,” Vie française (Québec), 15 (1960–61): 237–41. Adjutor Rivard, “Legendre,” RSC Trans., 3rd ser., 3 (1909), sect.i: 73–86. Camille Roy, À l’ombre des érables; hommes et livres (Québec, 1924), 107–20. Régis Roy, “Réponses: les ouvrages de Napoléon Legendre,” BRH, 14 (1908): 254–55. RSC Trans., 3rd ser., 2 (1908), proc.: xviii-xix (obit. notice and portrait facing p.xviii).

Cite This Article

Aurélien Boivin, “LEGENDRE, NAPOLÉON (baptized Gabriel-Narcisse-Napoléon),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 23, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/legendre_napoleon_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/legendre_napoleon_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Aurélien Boivin |

| Title of Article: | LEGENDRE, NAPOLÉON (baptized Gabriel-Narcisse-Napoléon) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | January 23, 2025 |