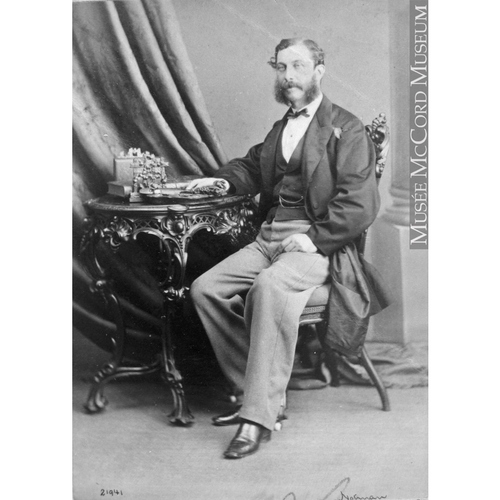

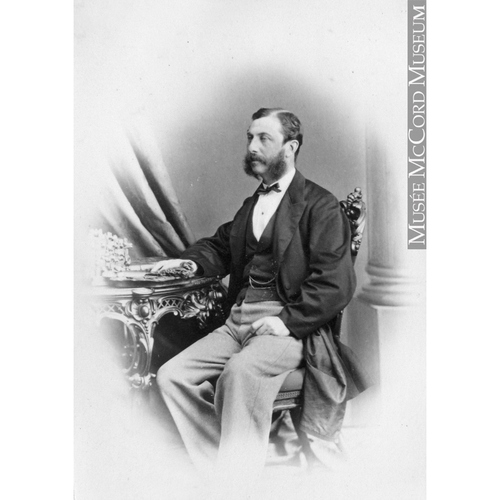

RICHEY, MATTHEW, Wesleyan Methodist minister and educator; b. 25 May 1803 at Ramelton (Rathmelton), County Donegal (Republic of Ireland); m. in 1825 Louisa Matilda Nichols at Windsor, N.S., and they had five children; d. 30 Oct. 1883 at Halifax, N.S.

Matthew Richey’s devout Presbyterian parents secured for him a solid classical education in the expectation that he would enter the ministry. Although not permitted to attend other churches, he managed to participate in Methodist prayer meetings and became convinced that “the Methodists are a peculiar people the people of God . . . with them I will by the grace of God, both live and die.” Following his conversion, he accompanied his brother to Saint John, N. B., in 1819, and found work as a solicitor’s clerk and later as a tutor in the local grammar school. He soon attracted the attention of the Reverend James Priestley, who persuaded him to become a candidate for the Methodist ministry. At the Nova Scotia District meeting in 1820, he was appointed assistant to the Reverend Duncan McColl* at St David, N.B., and in 1821 became a regular probationer in the Nova Scotia District of the British Wesleyan Conference, one part of the far-flung missionary enterprise supervised by the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society. He completed his probation in 1825 and was admitted to full connection.

Evangelical zeal and learning were nicely balanced in Richey’s preaching. His first sermon before the district meeting was delivered “in a most pleasing, systematic and devout manner and without apparent effort.” Within a decade he acquired a reputation as “a preacher never to be forgotten by any who listened to him.” His published Sermons delivered on various occasions are scholarly, exegetical, and heavily laden with classical and historical allusions, but do not suggest the “gentle and persuasive eloquence” which was “equally admired by the most cultivated and intelligent, and by the simple and unlettered.” Nor can one perceive in them the preacher who apparently moved easily from the most important Methodist pulpits in Halifax to the streets and squares where he spoke to the passing crowds. Clearly, however, he was most comfortable in an orderly and decorous atmosphere in which the sonorous periods of classical rhetoric could be delivered in the passionate tones that so impressed his listeners.

Richey served on several circuits in the Maritimes before being transferred in 1835 to Montreal in the Lower Canada District. In 1836 he was appointed the first principal of Upper Canada Academy in Cobourg, the Methodist coeducational preparatory school that became Victoria College in 1841. Richey was installed formally on 18 June 1836 and remained in office until 1840.

From 1836 to 1850, when he returned to Nova Scotia, Richey played an active part in the development of Methodism in the Canadas, a role that can be understood only in the context of the complex relationship between Canadian and British Methodism. Three years before Richey’s arrival in Upper Canada, the British Wesleyans and the Canadian conference had entered into union. During Richey’s principalship, relations between the two bodies deteriorated steadily, largely because the British Wesleyans insisted that the Canadian leaders were disloyal agitators whose campaign for civil and religious liberty would subvert the constitution, the British connection, and the principle of state support for religious institutions. The Canadian Methodists, led by Egerton Ryerson and his brothers, John* and William*, affirmed their loyalty and their determination to secure their rights as “Christians and as Canadian British subjects.” They also refused to turn their journal, the Christian Guardian (Toronto), into a bland purveyor of religious news.

Richey, whose attitudes had been shaped by his northern Irish upbringing and the conservative outlook of the Wesleyans in Britain and Nova Scotia, was insistent that Methodism should be purified “from the pollution of politics” and stamped “with the resplendent signet of true British loyalty.” In January 1840 he joined another Wesleyan minister, Joseph Stinson*, in assuring Governor General Charles Edward Poulett Thomson* that “the Church of England being in our estimation The Established Church of all the British Colonies, we entertain no objection to the distinct recognition of her as such,” a principle that the Canadian Methodists would not accept. He strongly supported the unsuccessful efforts of his colleagues, Stinson and Robert Alder*, to bring the Canadian conference into line; their charges against Egerton Ryerson were put forward by Richey at the conference held in Belleville in June 1840. Soon afterward Stinson and Richey attended the fateful 1840 session of the conference of British Wesleyans in England at which the union of 1833 was dissolved.

On returning to Canada, Stinson and Richey organized a new Canada Western District under the supervision of the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society for those preachers and laity who were determined not to accept the jurisdiction and policies of the Canadian conference. Richey was secretary of this body in 1840 and 1841 and chairman from 1842 to 1845. Campaigning vigorously for the consolidation and extension of the Wesleyans’ influence in Canada West, he bitterly resisted any suggestion that the two Methodist groups should reunite. He and his brethren asserted that it would be “a national calamity” to prevent the diffusion of British Methodism in Canada West, since through its scriptural influence the “triumph of democracy” might be “for ages, perhaps for ever averted” in the colony.

Nevertheless, threatened by dissension at home, the rising costs of the missions in British North America, and the emergence of Anglo-Catholicism, the British conference moved toward reconciliation with the Canadians. Richey, transferred to Montreal in 1845 to become chairman of the Canada Eastern District, participated in the 1846 meeting of the British conference at which reunion between the British and Canadian conferences was accepted in principle. As the missionary society’s representative at a special session of the Canada Western District meeting in February 1847, he sought to allay the fears of his brethren about the proposed union, even though he himself was still suspicious and critical of the Ryersons. Similarly, at a subsequent meeting between Robert Alder, the British conference representative, and the Wesleyan ministers, he emphasized that he had worked for reunion “at the sacrifice of the finest feelings of his heart.” Characteristically, at the service which followed the passage of the terms of union by the Canadian conference in June 1847, Richey “imbued with the spirit of a seraph carried the audience with him in his feelings of charity and love while delivering his impromptu but unequalled address.”

In 1847 and 1848 Richey was co-delegate or vice-president of the Canadian conference and in 1849 he became president. Moreover, although many Methodists, including Anson Green*, had criticized his record in managing the finances of Upper Canada Academy, he was offered the principalship of Victoria College. Unfortunately, in October 1849 he was severely injured in a carriage accident. This misfortune evidently strengthened his long-standing inclination to return to the Maritime provinces.

In 1850 Richey became involved in the anxious deliberations of the conference and the Victoria College board about the possibility of incorporating Victoria into the University of Toronto. It was suggested that Richey might be appointed supervisor of Methodist divinity students and professor of rhetoric and English in the university. He concluded, however, that this project was designed in someone else’s interest and left abruptly for Nova Scotia. Later he commented that “the university is an anomalous semi-infidel affair in which religion, while ostensibly recognized, is virtually proscribed. Such an Institution is . . . no place for a Methodist Minister.”

Following his return to Nova Scotia, Richey was appointed in 1852 chairman of the newly formed Western District, which had been created partly to provide a suitable place for him. As chairman, he was involved in the discussions which preceded the formation of the Conference of Eastern British America, a project that had been first considered in the early 1840s. Although he did not wish to take any step that would lead to independence from the British conference, Richey cooperated effectively with the missionary society in this matter. When the new conference was established in 1855, Richey became co-delegate, and from 1856 to 1861 and again in 1867–68 he served as president; during the years 1864–67 he was chairman of the Prince Edward Island District. His last official position before his retirement in 1870 was as chairman of the Saint John District.

Matthew Richey held the highest positions open to him in the Methodist community, but he does not seem to have been an aggressive ecclesiastical statesman in the mould of his colleagues, Robert Alder, Egerton Ryerson, or Enoch Wood. Rather, he was an outwardly gentle and courteous man with a high estimate of his own importance and an intense commitment to Wesleyan Methodism, political conservatism, and the preservation of close religious and political links between Britain and British North America. In private he often enunciated his views in vitriolic and intemperate language, behaviour which may well have led his superiors to distrust his judgement. He was essentially a powerful evangelical preacher who, along with many others, appears not to have sensed the potential contradiction between the achievement of holiness in this world and acceptance of the existing political and social order. It would be easy simply to note with John Saltkill Carroll that Richey had a “ready command of the most exuberant and elevated language, amounting almost to inflation of style,” and to dismiss him as an overrated orator. In reality, however, he epitomized many of the characteristics of Wesleyan Methodism in his time. Besides supporting close links with the English Wesleyan tradition, he helped to foster in British North American Methodism concern for the institutional status of his church, political quietism, and hostility to cultural activities such as the theatre.

Richey’s services to Methodism were recognized by Wesleyan University, Middletown, Conn., with the award of an ma in 1836 and a dd in 1847. He was described by John Fennings Taylor as “the most eloquent and accomplished speaker of all the Methodist connection in the Dominion of Canada.” His friend and colleague, the Reverend John Lathern*, commented that Richey’s biography of William Black*, the founder of Methodism in the Maritime provinces, was “a production of sterling excellence.” He added: “The testimony of some who sat beneath his ministry is to the effect that the most heart-searching appeals they ever listened to from the pulpit were from his lips.” “His memory,” said Victoria’s president Samuel Sobieski Nelles, “will be fondly cherished by all who knew him.”

Matthew Richey died after a lengthy illness at Government House in Halifax, the official residence of his son, Lieutenant Governor Matthew Henry Richey*. No more appropriate place could have been found for one so closely identified with the history of Methodism in the North Atlantic world of the 19th century.

Matthew Richey was the author of A funeral discourse, on occasion of the death of Mrs. J. A. Barry: delivered at the Methodist chapel, Halifax, on the evening of Sunday, 13th January, 1833 (Halifax, 1833); The internal witness of the spirit, the common privilege of Christian believers: a discourse, preached at Halifax, before the Wesleyan ministers of the Nova-Scotia district, on the 24th of May, 1829 (Charlottetown, 1829); A letter to the editor of The Church; in answer to his remarks on the Rev. Thomas Powell’s essay on apostolical succession (Kingston, Ont., 1843); Life and immortality brought to light by the gospel: a sermon (Halifax, 1832); A memoir of the late Rev. William Black, Wesleyan minister, Halifax, N.S., including an account of the rise and progress of Methodism in Nova Scotia . . . (Halifax, 1839); The necessity and efficiency of the gospel: a sermon preached before the Branch Methodist Missionary Society of Halifax, Nova-Scotia, February 11th, 1827 (Halifax, 1827); Persuasives to active benevolence: a sermon, preached at the Wesleyan chapel, Halifax, on Christmas evening, 1833, for the benefit of the poor (Halifax, 1833); A plea for the confederation of the colonies of British North America; addressed to the people and parliament of Prince Edward Island (Charlottetown, 1867); A sermon occasioned by the death of the Rev. William Croscombe, preached in Windsor, 30th October, and in Halifax, 6th November, 1859 (Halifax, 1859); A sermon on the death of the Rev. William M’Donald, late Wesleyan missionary; preached at Liverpool, Wednesday, March 19, and in substance at Halifax, on Sunday, March 30, 1834 (Halifax, 1834); A sermon preached at the dedication of the Wesleyan Methodist Church, Richmond Street, Toronto, on Sunday, June 29, 1845, and of the Wesleyan Methodist Church, Great St. James Street, Montreal, on Sunday, July 27, 1845 (London and Montreal, 1845); Sermons delivered on various occasions (Toronto, 1840); A short and scriptural method with Antipedobaptists, containing strictures on the Rev. E. A. Crawley’s treatise on baptism, in reply to the Rev. W. Elder’s letters on that subject (Halifax, 1835); Two letters addressed to the editor of The Church, exposing the intolerant bigotry of that journal, and animadverting especially on the spirit and assumptions of an editorial article which appeared in its columns on the 7th April, 1843 (Toronto, 1843); and, with Joseph Stinson, of A plain statement of facts, connected with the union and separation of the British and Canadian conferences (Toronto, 1840). Also of interest is Catalogue of books in theology & general literature, (from the library of the late Rev. Dr. Richey), among which are many rare & valuable works, now offered for sale by Messrs. MacGregor & Knight, stationers and booksellers, 125 Granville St., Halifax, N.S. (Halifax, 1885).

Methodist Missionary Soc. Arch. (London), Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Soc., Corr., Canada (mfm. at UCA). UCA, Matthew Richey papers, 1841–54. United Church of Canada, Maritime Conference Arch. (Halifax), Matthew Richey papers, 1833–59 (mfm. at UCA). Carroll, Case and his cotemporaries. Centenary of Methodism in Eastern British America, 1782–1882 (Halifax and Toronto, [1882]). John Lathern, “The Reverend Matthew Richey, D.D.,” Canadian Methodist Magazine, 21 (January–June 1885): 259–68. Methodist Church (Canada, Newfoundland, Bermuda), Nova Scotia Conference, Minutes ([Halifax]), 1884. Wesleyan Methodist Church in Canada, Minutes (Toronto), 1824–45; 1847–50. Wesleyan Methodist Church of Eastern British America, Minutes (Halifax), 1855–74. Christian Guardian, 7 Nov. 1883. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose, 1888). Notman and Taylor, Portraits of British Americans. G. E. Jaques, Chronicles of the St. James St. Methodist Church, Montreal, from the first rise of Methodism in Montreal to the laying of the corner-stone of the new church on St. Catherine Street (Toronto, 1888). D. W. Johnson, History of Methodism in Eastern British America, including Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Bermuda . . . ([Sackville, N.B.], n.d.). Sissons, Egerton Ryerson. T. W. Smith, History of the Methodist Church within the territories embraced in the late conference of Eastern British America . . . (2v., Halifax, 1877–90).

Cite This Article

G. S. French, “RICHEY, MATTHEW,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 21, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/richey_matthew_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/richey_matthew_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | G. S. French |

| Title of Article: | RICHEY, MATTHEW |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | January 21, 2025 |