Source: Link

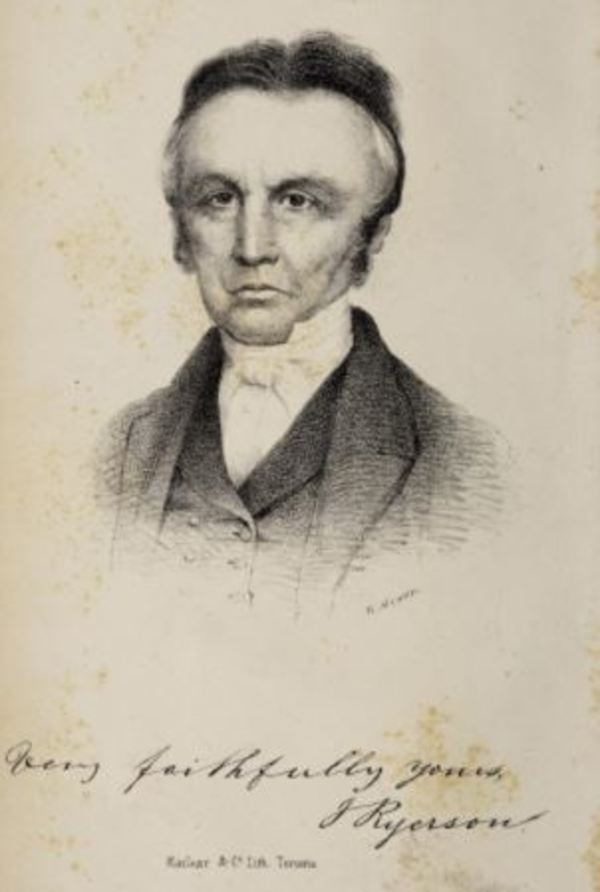

RYERSON, JOHN, Methodist minister; b. at Charlotteville, Norfolk County, U.C., 12 June 1800, fourth son of Colonel Joseph Ryerson, a loyalist of Dutch and Huguenot ancestry, and of Sophia Mehetabel Stickney; m. Mary Lewis in 1828 by whom he had a son and a daughter; d. 8 Oct. 1878, at Simcoe, Ont.

Five of Colonel Ryerson’s six sons entered the Methodist ministry despite his strong disapproval. After serving with his father as a volunteer on special service during the War of 1812, John was converted to Methodism in the evangelical awakening which followed the war in Upper Canada as were his two older brothers George* and William Ryerson and, subsequently, his two younger brothers Egerton* and Edwy. In 1820 he began preaching as supply and in 1821 he was received on trial on the Ancaster circuit. Two years later, on the Yonge Street circuit, he was ordained deacon and in 1825, on the Perth circuit, elder. In the ensuing years he served as presiding elder, chairman, or superintendent of almost every circuit or district in the province, and in 1843 he was elected president of the Wesleyan Methodist Church in Canada. Subsequently, for nine consecutive years from 1849 to 1857, he was elected co-delegate, or vice-president, of the church, which was then, under the terms of reunion with the British conference, the highest post to which his colleagues in the Canadian conference could elect him.

John took, with his brothers William and Egerton, an active part in resolving many of the issues which confronted the Methodists in Upper Canada, particularly during the period from the mid-1820s to the mid-1850s. He was a leader in the fight, which he described as “a desperate struggle,” against the schismatic body of Methodists, led by Henry Ryan*. At the same time, he advocated the separation of the church in Upper Canada from the American Methodist Episcopal Church of which it was then a part; as one of five delegates from the Canada conference to the American general conference in Pittsburgh in 1828, he was instrumental in bringing about the amicable separation that year which resulted in the establishment of an independent Methodist Episcopal Church in Canada [see Richardson]. In 1832 he proposed a union with the British conference of the Wesleyan Methodist Church to avoid wasteful competition and duplication of effort, and to affirm the essential loyalty of the Canadian Methodists. The Wesleyan Methodist Church in Canada was formed but the union collapsed in 1840. He again expressed concern at the harm done by having two rival Methodist bodies and urged another attempt at union. In 1846 he and Anson Green were chosen delegates to the British conference where they successfully advocated this cause.

John, William, and three others were asked in 1829 to study the advisability of establishing a Methodist seminary of higher learning and, in 1830, he and William were named to a new committee to further the project. It selected Cobourg as the site for the Upper Canada Academy, which later became Victoria College. In 1835 John was made one of the first five visitors to the college; they were given the responsibility of working with the trustees in appointing the principal and teachers, drafting regulations, managing the affairs of the institution, and reporting upon its academic and financial state each year to the conference. In 1841 he was, with William and Egerton, among those who petitioned the Legislative Assembly for a charter and an endowment for the college. Throughout these years, when the college was in financial difficulties and its survival sometimes in doubt, John signed notes on its behalf, borrowing money on his personal credit to meet its indebtedness even though these debts were incurred against his advice. He continued for more than three decades to work actively for the college, serving terms as treasurer and chairman of the board.

The modest extent of John’s own formal education is reflected in his remarkably colourful and imaginative spelling. But his qualities of intellectual distinction and his feeling for language are unmistakable. At the 1837 conference John was named, as were William and Egerton, to the Book and Printing Committee, forerunner of the Ryerson Press, which supervised the publishing of the Christian Guardian, in that period the most widely read and influential newspaper in Canada, and of other productions, as well as overseeing the sale of books from Britain and the United States of interest to Upper Canadian Methodists. John served as book steward from 1837 to 1841.

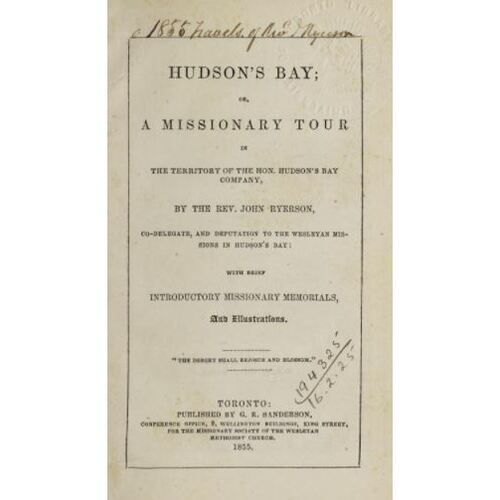

The range of John’s intellectual and literary interests is, however, more substantially indicated by his own writing which included an extensive correspondence, diaries and journals, and numerous notes and papers on Methodist history and policy. Although much of this material remains unpublished, or has been misplaced, a good deal of his writing was apparently published without attribution, perhaps because of an aversion which John had to seeing his own name in print. His name appears, however, at the head of five of the 18 chapters of Canadian Methodism; its epochs and characteristics, and it may well be that this book was really the work of John, annotated by Egerton and published in his name in compliance with his brother’s wishes. John’s book, Hudson’s Bay; or, a missionary tour in the territory of the Hon. Hudson’s Bay Company . . . , published in 1855, which records the perilous expedition he led the previous year from Sault Ste Marie to Hudson Bay, via Red River, and from there to England, furnishes the most accurate and reliable account available of this early trade route. The expedition was made with a view to the assumption by the Canadian Methodist Church of responsibility for missionary activity in the area. He described the promise of parts of this land and, in contrast to some other writers of the period, looked ahead to its settlement and development with confident enthusiasm.

It was characteristic of John to undertake so difficult a journey in his 55th year. Throughout his life he worked to excess and he was frequently exhausted by these exertions, with a consequent strain on his health. This strain and chronic ill-health led him to some dependence at times, in particular immediately following his journey, upon opium and brandy, which aroused acute concern amongst his Methodist brethren. At the conference of 1858, which had in any case an undercurrent of hostility towards the Ryerson brothers, a committee of ten was appointed to investigate his character and its report resulted in his being “left without a station” and his name being “dropped from the Minutes of Conference for One Year.” In the following year he was restored to his accustomed place, however, and chosen a member of the special committee entrusted with conference business between the annual sessions. From 1860 until his death he was superannuated at Brantford and at Simcoe, continuing an active work in the ministry despite his precarious health.

John was in age and affection the brother nearest to Egerton who, in the years when his career was in the making, never took a step without consulting “this brother who commanded his entire respect and affection.” Egerton, writing in 1843, records that he regarded John as “for many years the most cool and accurate judge of the state of the public mind” of any man he knew in Canada. Described by Egerton as “a life-long Conservative,” John was the principal architect of the strategy advocated by Egerton and, in general, followed by the Methodists, of support for loyal reform, within the constitution, aimed at civil and religious liberty. In the difficult period before the 1837 rebellion he cautioned Egerton constantly to “take good care not to lean a hair’s breadth toward Radicleism.” He repeatedly expressed concern that the Methodists had become too much associated with extreme Reformers, “a banditti of compleat vagabonds,” so that it was “absolutely necessary to disengage ourselves from them entirely. You can see that it is not Reform, but Revolution they are after.” He rejoiced that in the critical 1836 elections not “a ninny of them was elected in the Bay of Quinte District” where “the preachers and I laboured to the utmost extent of our ability to keep every scamp of them out and we succeeded.”

Nevertheless John was far from being a stern and unbending Tory. Once the rebellion had been coped with, he renewed his advocacy of constitutional reform and urged the Methodists to pursue “the enlightened, just and liberal course we have been wont to persue.” He signed and presented to Lieutenant Governor Sir George Arthur* a petition, on behalf of some 4,000 signators, asking that the lives of the rebels Samuel Lount* and Peter Mathews* be spared and when the petition was rejected he followed the two men to their execution. Similarly, in the wake of the rebellion, he protested arbitrary measures including the indiscriminate keeping of scores of persons in prison awaiting trial. He felt it necessary for “the friends of Civil and Religious liberty” to remain vigilant, noting that “it is a great blessing that Mackenzey [William Lyon Mackenzie*] and Radicalism are down, but we are in immediate danger of being brought under the domination of a military and high-church oligarchy, which would be equally bad if not infinitely worse.”

Often seemingly aloof, austere, and taciturn in public, John was in the privacy of his family and friendships warm, kindly, and forthcoming. In C. B. Sissons*’ assessment, “Seldom has a Canadian home produced four such men as George, William, John and Egerton Ryerson. Differing in character and talent, they all had upon them the mark of greatness.” Of the brothers, John was pre-eminently the statesman and the practical man of public and ecclesiastical affairs. He was for several decades probably the most influential man in the councils of the Methodist Church in Upper Canada.

John Ryerson, Hudson’s Bay; or, a missionary tour in the territory of the Hon. Hudson’s Bay Company . . . (Toronto, 1855).

Methodist Missionary Society (London), Correspondence, continent of America. UCA, A. E. Ryerson papers. John Carroll, Case and his cotemporaries; [ ] Past and present, or a description of persons and events connected with Canadian Methodism for the last forty years (Toronto, 1860). Christian Guardian (Toronto), 1829–78. [Ryerson], Story of my life (Hodgins). Cornish, Cyclopædia of Methodism, I. Dom. ann. reg., 1878, 364–65.

G. S. French, Parsons & politics: the rôle of the Wesleyan Methodists in Upper Canada and the Maritimes from 1780 to 1855 (Toronto, 1962). G. F. Playter, The history of Methodism in Canada: with an account of the rise and progress of the work of God among the Canadian Indian tribes, and occasional notices of the civil affairs of the province (Toronto, 1862). A. E. Ryerson, Canadian Methodism; its epochs and characteristics (Toronto, 1882). A. W. Ryerson, The Ryerson genealogy; genealogy and history of the Knickerbocker families of Ryerson, Ryerse, Ryerss; also Adriance and Martense families; all descendants of Martin and Adriaen Ryerz (Reyerszen), of Amsterdam, Holland, ed. A. L. Holman (Chicago, 1916). Sissons, Ryerson. Clara Thomas, Ryerson of Upper Canada (Toronto, 1969).

Cite This Article

Thomas H. B. Symons, “RYERSON, JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ryerson_john_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ryerson_john_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | Thomas H. B. Symons |

| Title of Article: | RYERSON, JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1972 |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |