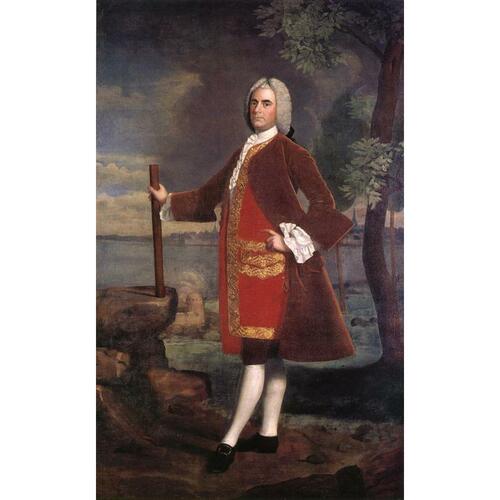

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

WALDO, SAMUEL, Massachusetts merchant, land speculator and politician; brigadier-general in the 1745 expedition against Louisbourg; b. 1695 at Boston, son of Jonathan Waldo and Hannah Mason; m. 1722 Lucy Wainwright, by whom he had three sons and two or three daughters; d. 23 May 1759, on the Penobscot River, near present-day Bangor, Maine.

Samuel Waldo’s chief commercial interest was land speculation on a grand scale. He had a huge tract of land between the Penobscot and Muscongus rivers (present-day Maine), and there he settled some 40 German-speaking families in 1740. In 1730 Waldo had purchased from John Nelson*, the aged heir of Sir Thomas Temple*, the questionable claim to Sir William Alexander*’s 1621 patent to land in Nova Scotia. Waldo spent much time in London during 1731–32 and again in 1737–38 attempting to validate this claim to virtually all of the land “lying between the River St. Croix and St. Lawrence.” During his negotiations he presented to the British authorities, probably in 1738, a perceptively drafted memorial in which he proposed “To begin upon the Immediate settlement of the said Tract of Land by a considerable number of Familys from Switzerland, the Palatinate and other parts adjacent.” At least 2,000 “Foreign Protestant” families were to be settled in the colony at Waldo’s expense within a period of ten years. Waldo hoped that his settlement would, among other things, neutralize significantly what he conceived to be the growing power of France in North America.

Even though his proposal for Nova Scotia was rejected in 1738, Waldo’s interest in that area persisted. In 1740, for example, anticipating a declaration of war between France and Great Britain, he gave the Duke of Newcastle a “Plan for the Reduction of Cape Breton” and of New France. In the following year, the new governor of Massachusetts, William Shirley, one of Waldo’s closest friends, was also given a copy of the “Plan.” It is not surprising, therefore, that during the winter months of 1744–45, Waldo was among the most enthusiastic Massachusetts proponents of an expedition against Louisbourg, Île Royale (Cape Breton Island). Confronted by serious financial difficulties, he probably saw in the Louisbourg project an excellent opportunity to protect his land investments in northern Maine, then threatened by possible French-Indian assaults, and also to have his claim to much of Nova Scotia finally recognized by the British government. In addition, he realized that a major military expedition would result in the creation of a vast new reservoir of patronage and Waldo was probably eager to benefit fully, financially and otherwise, from such a windfall.

Soon after the decision of the Massachusetts General Court on 25 Jan. 1744/45 (o.s.) to organize an expedition against Louisbourg, Waldo apparently asked Shirley for the post of commander-in-chief. But Waldo lacked the necessary popular appeal and his close association with the governor must have been resented by some members of the General Court. Consequently Shirley rejected Waldo’s offer, but not before awarding him a brigadier-general’s commission and appointing him second in command to William Pepperrell – the commander-in-chief of the Massachusetts troops. Waldo expended a great deal of time and energy in raising volunteers for his 2nd Massachusetts Regiment. According to his own calculation he was responsible for the enlistment of approximately 850 men – over 20 per cent of the total number of New England volunteers.

Soon after landing on Île Royale, Pepperrell ordered Waldo on 2 May to march his regiment to the Grand or Royal battery situated on the northeast shore of the inner harbour, approximately one mile by sea from both the town of Louisbourg and the Island battery. The battery had been captured early that morning by William Vaughan, who had found it empty. Waldo’s task was to supervise the drilling out of the spiked cannon and to begin the bombardment of the western walls of the fortress. He soon grew tired of the monotony of siege warfare, however, and offered, sometime before 12 May, to lead an assault against the Island battery. With this battery in New England hands, it was expected that Louisbourg would quickly surrender. Pepperrell, who had received a similar offer from William Vaughan, decided to reject both and to delay the assault on the Island battery indefinitely.

Later in May, however, under pressure from Commodore Peter Warren, commander of the British fleet blockading Louisbourg, Pepperrell changed his mind. He selected Waldo to organize the attack on the Island battery. On 22 May Waldo managed to enlist volunteers who marched to the beach near the Grand battery after sunset and prepared their boats for the assault. Waldo cancelled the raid, however, because there were no officers to lead the men and many volunteers were drunk. Moreover, he observed to Pepperrell, “The night oweing to the moon & the northern lights was not so agreeable.” On the following night, which was calm and foggy, Waldo persuaded Arthur Noble and John Gorham to command an expedition of 800 men. By the time the whaleboats neared the battery, however, the two officers had disappeared from view. The 800 volunteers decided to return to the Grand battery. On 26 May Waldo dispatched a force of 400 volunteers against the Island battery. This one reached its target, but the invaders were easily turned back by the French.

After the capture of Louisbourg, Waldo, with other New England officers acting as a council, participated in the governing of the fortress until Warren’s commission as governor finally arrived in the spring of 1746. Waldo returned to Massachusetts to command a proposed expedition against Fort Saint-Frédéric (Crown Point), but it never took place.

In 1749 Waldo became involved in a bitter dispute with Shirley over the settling of the colony’s military accounts, and went to London to defend himself. During his sojourn there he had an audience with King George II. On his return to Massachusetts, Waldo continued to be involved in colonial politics and in land speculation. He refused to abandon his claim to Nova Scotia, but it was never recognized in spite of his persistent pleas.

In 1757 he sent to William Pitt a detailed plan for the capture of Louisbourg, which had been returned to the French in 1748. Pitt used Waldo’s plan as the basis for his instructions to Major-General Jeffery Amherst* to capture Louisbourg in 1758.

Waldo died of apoplexy on 23 May 1759 while on a military expedition in Maine; he was accompanying Governor Thomas Pownall’s force of 400 men in taking possession “of the King’s ancient Rights, and establishing the same by setting down a Fort on the Penobscot River.”

PRO, CO 5/753. Boston Weekly News-Letter, 31 May 1759. PAC Report, 1886, viii–xii, cli–civi. “The Pepperrell papers,” Mass. Hist. Soc. Coll., 6th ser., X (1899), 3, 4, 6–10, 13, 16, 18–21, 23, 25–33, 36–38, 40–65, 139, 141, 143, 150–51, 154–55, 157, 166, 169, 172, 190, 192, 196, 198, 203, 208, 210, 212–15, 223, 231, 234, 271–72. PRO, JTP, 1754–58, 248. Bell, Foreign Protestants. McLennan, Louisbourg. New Eng. Hist. and Geneal. Register, XVIII (1864), 177. Rawlyk, Yankees at Louisbourg. J. A. Schutz, William Shirley: king’s governor of Massachusetts (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1961). Joseph Williamson, “Brigadier General Samuel Waldo, 1696–1759,” Maine Hist. Soc. Coll., 1st ser., IX (1887), 75–93.

Cite This Article

G. A. Rawlyk, “WALDO, SAMUEL,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 3, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 22, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/waldo_samuel_3E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/waldo_samuel_3E.html |

| Author of Article: | G. A. Rawlyk |

| Title of Article: | WALDO, SAMUEL |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 3 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1974 |

| Access Date: | January 22, 2025 |