Source: Link

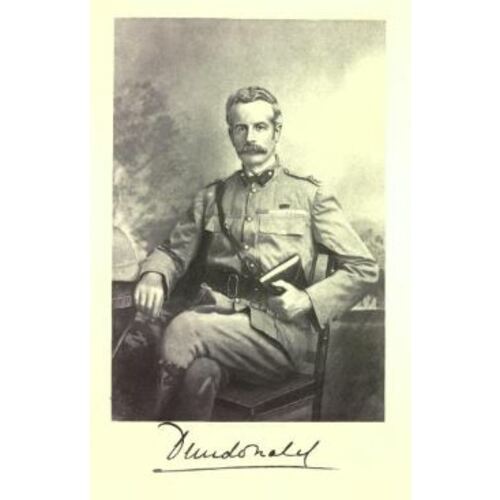

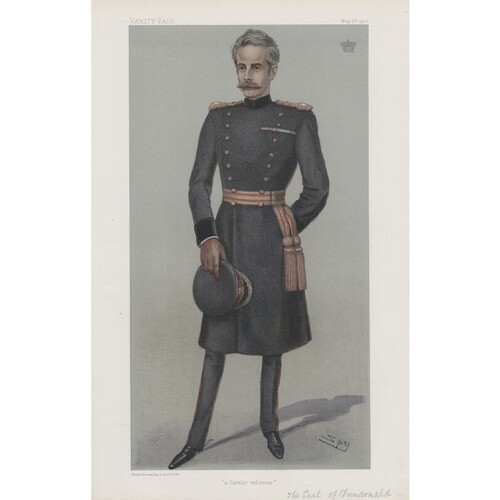

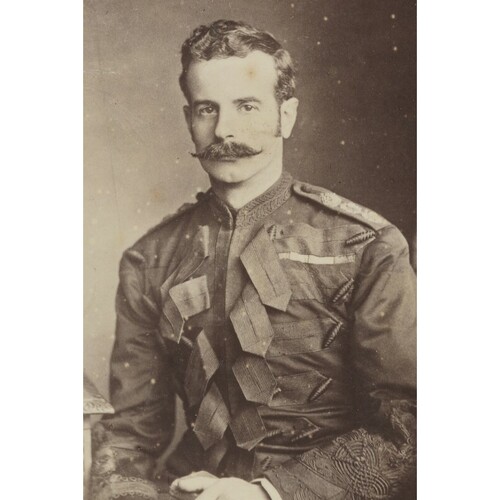

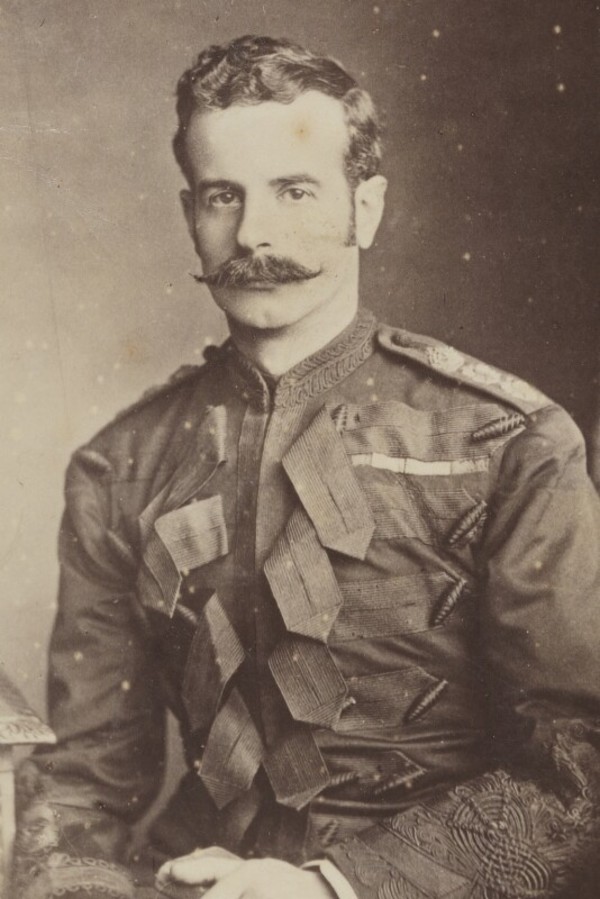

COCHRANE, DOUGLAS MACKINNON BAILLIE HAMILTON, 12th Earl of DUNDONALD, soldier and politician; b. 29 Oct. 1852 at Auchentoul House, Banff, Scotland, son of Thomas Barnes Cochrane, 11th Earl of Dundonald, and Louisa Harriet Mackinnon (MacKinnon); m. 18 Sept. 1878 Winifred Bamford Hesketh (1859–1924) in St Asaph, Wales, and they had two sons and three daughters; d. 12 April 1935 in Wimbledon (London), England.

The Cochranes had a long history of military and naval service in Scotland and elsewhere. Several served in what would become Canada, including Sir Thomas John Cochrane*. The second son of an aristocratic but undistinguished captain in the British army, Douglas, known as Lord Cochrane because his elder brother had died in infancy, was educated at a private school in Walton-on-Thames, England, and at Eton College. In 1870 his family purchased him a commission as a cavalry officer in the 2nd Life Guards. In 1884–85 he commanded the detachment of the unit that joined General Garnet Joseph Wolseley*’s expedition to rescue Major-General Charles George Gordon, who was besieged by Mahdist forces at Khartoum in the Sudan. Wolseley’s force arrived too late; Douglas became known in Great Britain as the despatch rider who brought news of Gordon’s death. In February 1885, while in the Sudan, Douglas learned that he had succeeded to the earldom upon his father’s death on 15 January. Dundonald was promoted lieutenant-colonel in June and brevet colonel in 1889; he assumed command of the 2nd Life Guards in 1895.

After the South African War began in October 1899, Dundonald was placed in charge of the Mounted Brigade (whose officers included Julian Hedworth George Byng) in the field force led by Sir Redvers Henry Buller. In February 1900 Dundonald came to the British public’s attention for helping relieve the besieged town of Ladysmith. The next month he received the rank of major-general. Between June and October the Canadian-raised Lord Strathcona’s Horse [see Donald Alexander Smith*] was attached to Dundonald’s reorganized unit, the 3rd Mounted Brigade, which participated in the battle of Belfast-Bergendal and the Lydenburg campaign and was disbanded in October. The commanding officer of Strathcona’s Horse, Samuel Benfield Steele*, regarded the earl as “a very fine soldier and perfect gentleman, so different from British officers sent to Canada,” an assessment shared by many of Steele’s officers and men.

Given Dundonald’s popularity among Canada’s South African War veterans, he was an obvious choice to replace Major-General Richard O’Grady Haly as general officer commanding the Canadian militia (GOC). Dundonald, who would arrive in Ottawa in July 1902, welcomed the appointment because of his “hereditary connection with the country” and his respect for the Canadian troops he had met in South Africa. Dundonald seemed well cast in his new role: he was an inventor whose accomplishments ranged from military vehicles to an improved teapot, and he was an outspoken reformer who supported the use of mounted infantry and the creation of what he called a volunteer “citizen army.” Yet the British War Office had harboured reservations about his fitness for the position, and it soon became clear that he had serious faults. Governor General Lord Minto [Elliot*] was among the first to perceive Dundonald’s eccentricity, vanity, and political partisanship. Minto, who had hoped that the War Office would appoint a man of tact, would privately describe “Dundoddle” as a “vain, unreasonable creature,” a “dangerous demagogue,” a “petulant baby,” and a “crank with a brain the size of a fruit head” who was distrustful, conspiratorial, and a careless administrator.

Dundonald soon joined battle with Sir Frederick William Borden*, the minister of militia and defence in Sir Wilfrid Laurier*’s Liberal government. They clashed over a variety of issues: funding, the site of a central training camp, Dundonald’s personal expenses, a defence plan that Dundonald wanted to outline in his first annual report, which he claimed had been suppressed by Borden, and, especially, Borden’s refusal to support a costly scheme to build fortifications along the Canadian–American border. Their relationship was severed when Borden proposed an amendment to the Militia Act that would create a council to advise the minister and establish civilian control over the militia. Dundonald rightly saw this change as an erosion of the GOC’s power. When his private and persistent appeals to the British government to block Borden’s designs failed, the general decided to fire the heather.

At a large banquet for militia officers held in Montreal on 3 June 1904, in the presence of a reporter and during an election year, Dundonald informed his audience of a “gross instance of political interference,” committed by acting minister of militia and defence Sydney Arthur Fisher* and condoned by Borden, in the selection of officers for the 13th (Scottish) Light Dragoons, an Eastern Townships regiment led by Charles Allan Smart. Dundonald’s action contravened the king’s regulations, since he was subordinate to the Canadian government as represented by the minister. Although Minto had little sympathy for Dundonald (and even less for his collaboration with Conservative politician Samuel Hughes*), he attempted to mediate the subsequent conflict between the government and the general. Unrepentant, Dundonald told Minto that he hated Laurier and “wished to do him all the harm he could.” On 14 June the cabinet passed an order in council dismissing the earl from his command, and Minto signed it, much to the surprise and annoyance of Dundonald, who had believed that the governor general would support him. Convinced that the people of Canada were thoroughly aroused by his plight, Dundonald planned to run as a Conservative candidate in the next election and issued a manifesto, published in the Montreal Gazette on 20 June, explaining his decision to speak out against the government. His popular crusade, which was marked by large and enthusiastic demonstrations in Ottawa and Toronto, was cut short by his recall by the War Office on 19 July. To the throng that cheered him at the railway station when he left Ottawa a week later, Dundonald exclaimed, “Keep both hands on the Union Jack!” Long after his departure he would remain popular among some Canadians: he kept his 1903 honorary colonelcy of the 91st Highlanders [see James Robert Moodie] in Hamilton, Ont., until 1924, for example, and the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire in Ottawa established a Dundonald chapter in 1937.

Upon his return to Great Britain, Dundonald campaigned unsuccessfully for the creation of a British volunteer “citizen army.” During the First World War he hoped to lead Canadian troops but was denied a command. He headed an Admiralty committee on smoke screens in 1915 and tried to persuade the government of the importance of chemical warfare, revealing in the process a secret plan for disabling an enemy with smoke and sulphurous fumes that had been devised by his grandfather, the 10th earl. A Scottish representative peer in the House of Lords since 1886, Dundonald held that position until 1922, but otherwise lived a quiet life. He travelled, resided largely at his wife’s family estate in north Wales, and in 1926 published My army life, in which he challenged the description of Lord Minto’s role in the “Dundonald incident” in John Buchan’s memoir of the governor general. Dundonald died in 1935 at the age of 82. In the early 21st century, streets in Saskatoon and Toronto, a park in Ottawa, and the fitness centre of the country’s largest military base, the 4th Canadian Division Support Base Petawawa in Ontario, bear his name.

Douglas Mackinnon Baillie Hamilton Cochrane, 12th Earl of Dundonald, is the author of “Notes on a citizen army,” Fortnightly Rev. (London), new ser., 78 (July–December 1905): 627–39, and My army life (London, 1926).

LAC, R10811-0-X. NA, CO 42/896. National Library of Scotland (Edinburgh), mss 12365–803 (4th Earl of Minto, papers). NSA, MG 2, vols.63–223 (F. W. Borden fonds). Univ. of Birmingham, Cadbury Research Library, Special Coll. (Eng.), JC (Joseph Chamberlain coll.). Gazette (Montreal), 9, 20 June 1904. John Buchan, Lord Minto: a memoir (London, 1924). Can., House of Commons, Debates, 10 June 1904: 4580–620. Canadian annual rev., 1904. Carman Miller, The Canadian career of the fourth Earl of Minto: the education of a viceroy (Waterloo, Ont., 1980); A knight in politics: a biography of Sir Frederick Borden (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 2010); Painting the map red: Canada and the South African War, 1899–1902 (Montreal and Kingston, 1993). Desmond Morton, Ministers and generals: politics and the Canadian militia, 1868–1904 (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1970). Charles Stephenson, The admiral’s secret weapon: Lord Dundonald and the origins of chemical warfare (Woodbridge, UK, 2006).

Cite This Article

Carman Miller, “COCHRANE, DOUGLAS MACKINNON BAILLIE HAMILTON, 12th Earl of DUNDONALD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 20, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cochrane_douglas_mackinnon_baillie_hamilton_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cochrane_douglas_mackinnon_baillie_hamilton_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Carman Miller |

| Title of Article: | COCHRANE, DOUGLAS MACKINNON BAILLIE HAMILTON, 12th Earl of DUNDONALD |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2023 |

| Access Date: | January 20, 2025 |